A framework for institutional portfolio management borrows best practices from both higher education and private-sector industry to help technology leaders step up as institutional leaders in improving institutional performance.

With increased funding pressure, public scrutiny, and performance expectations, higher education institutions face challenges that compel them to undertake new practices to improve institutional performance. As chief information officers increasingly become strategic partners at the leadership table, it behooves them to become educated in the political and economic challenges facing the institution, not just the technological challenges. Even better than coming to the table with knowledge is to come to the table with solutions that will help improve institutional performance. In this article I point out similar challenges and practices from higher education and from private-sector industry and present a combined framework borrowing the best of both. IT leaders might recognize the triple-constraint challenge and portfolio-management techniques from their own experience, as the same concepts exist in higher education. Armed with the knowledge and the practical framework I elaborate in this article, technology leaders will find themselves better prepared to step up as institutional leaders of the future.

The Challenges

In 2006 the United States Department of Education released what is commonly referred to as the Spellings Report but is formally titled "A Test of Leadership: Charting the Future of U.S. Higher Education."1 The Spellings Report acknowledged higher education as one of America's greatest success stories and a world model but also called for improved performance in critical areas of access, cost and affordability, financial aid, learning, transparency and accountability, and innovation. No small charge.

The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education responded with a report titled "The Iron Triangle: College Presidents Talk about Cost, Quality, and Access," having interviewed over two dozen presidents from a variety of higher education institutions to add their perspective to the public dialogue.2 The presidents described the competing demands for reduced cost, maintained quality, and increased access as being in a reciprocal relationship they refer to as the iron triangle, wherein a change in one causes an inverse change in another. For example, reducing costs requires that an institution either sacrifice quality, such as with a higher student-to-faculty ratio, or decrease access, such as by offering less support to disadvantaged students. Increasing accessibility to a wider range of students increases costs through additional faculty, additional marketing campaigns, and additional support services.3 More, better, cheaper — each one takes from another. If you want more, you either have to spend more or decrease quality. If you want better, you either have to spend more or push through fewer units (students). If you want cheaper, you either have to push through fewer students or reduce quality.

The three-point iron triangle of cost, quality, and access in higher education bears a striking resemblance to the triple constraint of cost, quality, and time in the discipline of project and portfolio management.4 Both access and time refer in a sense to productivity or throughput, where providing access to a wider volume of students yields greater throughput of graduates and where longer time in a development schedule yields greater throughput of product. As in the iron triangle, making a change to one of the triple constraints creates a reciprocal change in another. For example, increasing throughput, e.g. speed of delivery, or increasing quality, e.g. features incorporated into the product, increases cost. To reduce costs you must either sacrifice quality, for example with fewer function points, or decrease speed, for example by reducing the number of people working on the project.5 While it's possible to realize efficiency gains that increase throughput without increasing cost, those gains are typically found in manufacturing environments or routine operations, not in industries that rely on highly educated, touch-intensive labor such as healthcare and education.6 In these industries, the same rule holds — more, better, cheaper — each one takes from another — but efficiency innovations are not easily realized.

Today's era of increased pressure to improve institutional performance is not new, although the intensity may be greater today than in bygone eras, as all five of "Porter's Five Forces" in the higher-education sector are changing simultaneously.7 The changes in industry forces manifest for higher education as:

- society shifting toward a view of higher education as an individual benefit rather than a social good, believing the expense should be borne by the individual and not the state;

- legislatures less inclined to fund higher education as a result of social pressures and less able to fund higher education as a result of fiscal pressures,

- for-profit institutions increasing in number and competitiveness,

- enrollments widening, adding increased pressure on institutional infrastructure;

- the student demographic shifting away from the traditional post-high-school four-year experience to a profile of older working adults or more transient students who stop and start or come and go among schools; and

- distance education breaking down geographic boundaries and expanding the competitor base from which students can select an institution.8

The Solutions

Both higher education and private-sector industry have experimented with or fully adopted solutions to the pressures they face. As institutions have faced reduced financial support from state allocations or private donors and endowments, they have often cut their budgets in an across-the-board method, each unit contributing its proportional share. It's not strategic, since you're cutting the good along with the bad indiscriminately, but it's simple, "fair," and easy to explain to internal stakeholders. Some institutions have attempted a more strategic approach of program prioritization, which evaluates all academic programs and administrative services and reallocates resources in alignment with strategic objectives.9 The practice of program prioritization in higher education has a parallel practice of portfolio management in private industry.10 Both serve to align limited resources with strategic objectives by intentionally allocating those resources among the organization's collection of programs. Both offer strengths to capitalize on in a combined framework, as described in this article.

About Portfolio Management

Portfolio management treats all operational programs as a collection of investments that should be evaluated in comparison with each other through a predefined set of cost-benefit-risk-alignment criteria. Organizational resources, e.g. funding, physical assets, and human time and effort, are then allocated in alignment with strategic objectives. A high-priority program may be augmented with additional resources, while a lower priority program sees its resources reduced or eliminated.11 A change in market conditions or environmental context may suggest a change in the portfolio mix to recalibrate the resource allocation, the risk-reward balance, and the strategic emphasis, or to pursue new opportunities. It is an ongoing process, not a one-time fix. Portfolio management has been applied in multiple disciplines, such as electrical engineering, biopharmaceuticals, global nonprofits, information technology, and facilities management, and incorporates a variety of organizational assets, such as human resources, facilities space, equipment, and funding.12 The success of this approach in improving corporate profits and share value is evidenced in the growing field of portfolio management now gaining a foothold in professional organizations such as ISACA and the Project Management Institute, even evolving to a formal standard.13

Definitions

Although related, portfolio management differs from project management or program management.

- Project management delivers a defined output within the prescribed time, budget, and scope. A project can be successfully executed even if it's an unneeded project — you can cut down the trees really well, but still be in the wrong forest.

- Program management delivers the intended benefits of an outcome, defining projects and balancing the resources that have been allocated in the process. Program management makes sure you're sent to the right forest.

- Portfolio management encompasses both program and project management, focusing on the selection of programs and allocating resources to achieve strategic objectives. Portfolio management makes sure that cutting down forests is the right business to be in, compared to other opportunities to achieve the mission.

About Program Prioritization

Program prioritization treats academic programs and administrative services as a collection of investments that should be evaluated in comparison with each other through a predefined set of criteria. Institutional resources, e.g. funding, physical assets, and human time and effort, are then allocated in alignment with strategic objectives. A high-priority program may be augmented with additional resources, while a lower priority program sees its resources reduced or eliminated.14 A change in market conditions or environmental context may suggest a new program to pursue and thus require a change in the resource allocation of the existing program mix. A program may be maintained for many reasons not readily apparent; for example, although a program does not directly align with the institutional mission, e.g. it is not a science program in a STEM land-grant, it could be a sustaining service, e.g. it is an English program that fulfills undergraduate education requirements. Program prioritization has been used by institutions to achieve quality recognition awards, add faculty lines and new programs, and open new colleges, in addition to absorbing dramatic budget cuts.15 Program prioritization is not without its critics. Just the word prioritization is inflammatory to some, implying that some programs could be more important than others. Although Dickeson's model calls for a highly inclusive and transparent process, inclusive and transparent are still open to interpretation and have been applied differently with different results, not always favorably viewed by the academy. While recommended as an ongoing process, program prioritization has often been applied as a one-time solution,16 reinforcing suspicions that it is reactive in nature.

Framework for Institutional Portfolio Management

Blending the best practices from each field into a framework of institutional portfolio management has the potential to create a powerful tool in support of institutional performance improvement.17 Although known by different terms, both practices rely on common elements of:

- governance of the portfolio and prioritization process by a group of stakeholders;

- predefined criteria to evaluate, select, and prioritize programs within the portfolio;

- use of criteria that address cost, value, and alignment to mission objectives;

- incorporation of other organizational plans, such as strategic and financial plans; and

- adaptation of common practices to the culture and characteristics of the organization.18

Primary differences are that program prioritization emphasizes a transparent and inclusive process to develop the criteria of evaluation; portfolio management emphasizes an ongoing process of continual rebalancing. Combining the best practices of both in a new framework that emphasizes transparency and inclusivity as well as continuity and balance offers institutional leaders a standard for guiding institutional performance improvement. I elaborate these points and explain the framework in the following sections.

Foundational Elements

Foundational elements are features that should be included in some way, shape, or form for the framework to be successfully implemented. They might also be called critical success factors — those things that must happen for the initiative to succeed.

- Evaluation criteria are developed through an inclusive and transparent process incorporating shared governance appropriate to the culture of the institution.

- All existing programs are assessed according to the evaluation criteria.

- Program resources are aligned according to institutional objectives: augmented, reduced, or eliminated as needed.

- Performance of the overall program portfolio is continually reviewed.

- New programs are evaluated for their potential to meet institutional objectives.

- When new programs are added, whether academic or administrative, the portfolio is reviewed and resources are redistributed to accommodate the new program with the intent of maintaining or improving overall performance.

- Strategic planning and financial planning are incorporated into program planning.

- Environmental demands and constraints are continually monitored and forecasted, e.g. changes in demographics, public support, or funding sources.

- Institutional goals and strategies are adapted in response to changing conditions.

- Goals, process, outcomes, and overall performance are continually assessed and communicated.

All of this is done persistently and methodically, rather than reactively. Institutional portfolio management thereby intentionally and continually maintains alignment of resources with strategic objectives to demonstrate and maintain high performance in relation to institutional goals and external pressures.

Process Overview

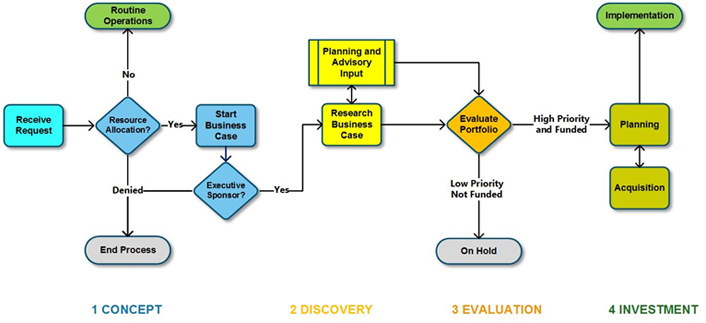

Figure 1 illustrates a process map of institutional portfolio management. At the heart of the process is ongoing portfolio review that can be conducted on a regular schedule and/or when information triggers a review, such as a revised strategic plan, financial plan, or changing environmental conditions. A review is also triggered when a new investment is proposed, i.e. a new academic or administrative program. New investments should move through the process in a stage-gate model, only proceeding to the next stage after clearance from the prior stage.

Figure 1. Institutional portfolio management process

1 Concept. A requester proposes a new investment. The portfolio manager "intakes" the request, collecting minimal essential information — enough to conceptualize whether it can be absorbed within routine operations or requires resource reallocation. If it requires resource reallocation, the portfolio manager confirms with the appropriate executive sponsor that they support the request. If the executive sponsor does not support the request, or if the CIO denies it for security or feasibility reasons, the request is stopped. Even if stopped, it is still useful to know for future reference that the need exists, as a similar request could emerge or the requester could seek alternative routes to address their needs. If the request is accepted and cannot be absorbed in routine operations, it must go into Discovery to gather additional information to inform evaluation and prioritization. Governance must clear any advancement into Discovery, as the information-gathering process requires time and effort, which is therefore drained from other investments.

2 Discovery. For a new intake, if resource allocation is required, a business case is developed using the predefined institutional criteria. As part of this process, subject matter experts or other advisors are consulted for needed information. Budget and financial plans, strategic plans, and environmental scans are also sources of information. When sufficient information has been compiled, the business case can move to the Portfolio Evaluation stage.

3 Evaluation. With necessary information compiled, the existing portfolio is reviewed to determine whether the proposed investment has the potential to improve overall performance compared to other programs and opportunities. New information — such as a revised strategic plan, a new budgeting cycle, or new market information — could also trigger a portfolio evaluation. Even without new information the portfolio should be regularly reviewed to assess opportunities for improvement. The portfolio reviewers are appointed according to the culture of the institution, including executives and governance representatives as appropriate. If the proposed investment is adopted, resources within the portfolio must be realigned to accommodate it — the money has to come from somewhere. Once funded, the proposed investment enters the portfolio as a new program.

4 Investment. In the investment cycle, a new project or program is planned, developed, and/or acquired according to standard practices, then executed along with the rest of the portfolio. Contracts are developed and professional services are engaged or hired.

Evaluation Criteria

Dickeson suggested an initial set of 10 criteria to evaluate programs, which institutions can consider and adapt to their own needs. Those criteria are briefly summarized below; for more in-depth explanation, refer to Dickeson's work.19

- History, development, expectations. Why was the program developed? Is it meeting its original intent and/or has it changed to adapt to changing needs?

- External demand. What do national statistics indicate about the present and future demand for this program by students and society? It's important not to react to shifting whims, such as an increase in demand for criminal forensics shortly following the introduction of a popular new television crime series. At the same time, it's important to understand regional and national long-term needs supported by evidence.

- Internal demand. Many academic programs do not host many majors or minors but do act as a critical service program to others, which should be taken into account.

- Quality of inputs. Inputs are the faculty, technologies, students, funding, and other resources that support a program. Inputs are relatively easy to measure and often used as a proxy for program quality.

- Quality of outcomes. Outcomes are the effectiveness measures of a program and much harder to evaluate than inputs. Recent trends in program assessment are driving the field more toward evaluation of outcomes, such as measuring learning outcomes or placement into careers or graduate programs.

- Size, scope, productivity. This criterion looks at volume and ratios to support it. How many students pass through the program? What is the ratio of faculty to students and the ratio of staff to faculty in the department? What is the density of faculty specialists or the ratio of tenured and tenure-track faculty to adjunct faculty?

- Revenue. Some programs bring in additional revenue to the institution, through enrollments but also through research grants, donor gifts, fees, ticket sales, or other sources. Service programs can also be viewed as subsidies for a net comparison.

- Costs. What are the relevant direct and indirect costs of a program? What additional costs would be needed to achieve performance goals for the program, or what efficiencies could be realized with the same or less investment?

- Impact. This criterion is a broad narrative of the positive effect the program has on the institution or the negative effect if the program were reduced or discontinued. It can include any information about the program that is important to understand in consideration of its future.

- Opportunity analysis. This final criterion considers new opportunities for the institution. What else should the institution pursue that it isn't already, or how could it be doing things differently to better effect?

Business Case

A business case involves an analysis of cost, benefit, risk, and alignment to objectives, with varying interpretations. Some define "business case" as a statement of benefit in a larger analysis of benefit, cost, and risk; some define the business case as the entire analysis. In any interpretation of a business case, cost is typically quantifiable, benefit and alignment are qualitative, and risk is a combination of quantitative and qualitative. For purposes of an institutional portfolio management framework, business case is defined as the complete analysis of cost, benefit, risk, and alignment, as defined below.

- Cost = a quantitative analysis of the upfront and ongoing costs of an investment. Costs include time and effort (labor) associated with the program, regardless of where the salary and benefits come from, as well as purchases. Upfront and ongoing costs are usually reported separately so that decision makers can see the initial outlay required as well as the annual commitment.

- Benefit = a narrative description of the benefits the institution will realize through the program. Although it's theoretically possible to quantify an expected return on investment as a benefit, in reality it's a pretty sophisticated organization that can do that with any validity. A narrative description is effective for most audiences, without the management system becoming larger than the outcome it manages.

- Risk = a combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis of probable risks and outcomes. Program risk in a technical organization is usually assessed in terms of the probability of an event or outcome occurring, expressed in a percentage, and the cost of impact if the event or outcome does occur, expressed in currency. Multiplying the probability times the impact, or the percentage times the currency, results in a risk score. But in spite of its seemingly quantifiable precision, the original estimate of probability and the original estimate of cost are still qualitative, albeit highly educated, guesses. The best approach is to show the quantitative math along with a qualitative narrative to explain the impacts. Program risk is not normally associated with academic program review or new academic program proposals. Present or future lack of interest in a program by prospective students or employers does constitute a risk to academic program success, as well as high overhead to provision or sustain operations compared to marginal interest among stakeholders.

- Alignment = a narrative describing how the program addresses strategic institutional objectives. Objectives can be explicitly published in a strategic plan or deduced from common knowledge, i.e. the strategic plan developed a few years ago doesn't necessarily speak to operating more efficiently, but we know in the current climate that increased efficiency is an emphasis.

A cost-benefit-risk-alignment analysis gives a comprehensive picture to decision makers of how a program contributes to the institution as well as how it consumes resources. Dickeson's 10 criteria of program prioritization correlate with the business case criteria of portfolio management, as categorized in table 1. Dickeson's list provides a more detailed explanation of information that should be included in a cost-benefit-risk-alignment analysis, which is just a different and more generalized way of grouping the same vital information. Some of the program criteria could be matched to more than one portfolio criterion; there are multiple ways to slice and dice. Table 1 illustrates one alignment.

Table 1. Comparison of portfolio management and program prioritization criteria

|

Portfolio |

Program Criteria |

Rationale |

|---|---|---|

|

Cost |

8. Costs |

Costs include time and effort of faculty, staff, and administration as well as space and other expenses. Revenue offsets cost and should be considered as part of the analysis. Costs needed to improve a program should also be considered. |

|

6. Size, scope, productivity |

Like revenue, size and productivity of the program could outweigh the costs with a net positive effect. A low-productivity program does not mean the program is struggling; different disciplines have different productivity scales. |

|

|

10. Opportunity analysis |

Opportunity "cost" is the loss to the institution of other alignment opportunities not realized because of the investment in this program. |

|

|

Benefit |

1. History, development, expectations |

A program may have historical or other value to an institution that does not necessarily align with strategic objectives; that doesn't mean the institution wants to discard all other benefits. |

|

2. External demand |

External demand is a benefit to the institution as it indicates positive attraction and attention by constituents. |

|

|

7. Revenue |

A low-revenue program does not mean the program is not important or should be cut. Revenue potential varies with discipline. It should also be considered as part of cost. |

|

|

Risk |

4. Quality of inputs |

Low-quality inputs indicate a program is at risk, as low-quality inputs are more likely to generate low-quality outcomes. |

|

5. Quality of outcomes |

Low-quality outcomes indicate a program is struggling and therefore a risk to the institution's overall success. |

|

|

Alignment |

3. Internal demand |

A program may be a service program to other programs, making it essential to the university and therefore in alignment with objectives, even though it does not itself attract any external attention. This could also be considered as part of benefit. |

|

9. Impact |

This catch-all criterion incorporates any information that doesn't fit in one of the other criteria. It should also be considered as part of benefit. |

The criteria are intended to provoke thought, be comprehensive, and adapt to individual institutions. The process for developing criteria is as important as the criteria themselves. It should be inclusive (everyone is included in the process and decision making, even if only in some representative manner) and transparent (everyone knows how decisions are made and what the decisions are). All programs, academic and administrative, must be evaluated by a set of criteria developed in advance. Some institutions have chosen to use different criteria for academic versus administrative programs. Certainly some of the more specific criteria do not apply to administrative programs, such as revenue or external demand or historical value. An administrative program such as "Payroll Processing" or "IT Network" will score zero points in any of those criteria, but will certainly score high on internal demand and impact. The criteria are intended to inform decision making, not become a mathematical substitute for human judgment. Administrative programs can be evaluated separately from academic programs, but at the end of the process, decisions must be made that distribute limited resources among all programs.

Example Template

A functional spreadsheet model of a business case template with scoring rubric is provided here for download.

Scoring Rubric

A scoring rubric can be used with any set of criteria. Like an academic grading rubric, it describes the characteristics that achieve a score for a given criterion. When evaluating something as complex as competing program investments, decision makers should not rely solely on a scoring rubric — the scores are merely informative. The value is as much in defining what low, medium, and high look like for each criterion. Defining the outcomes in writing, in advance, helps everyone understand what the outcomes might look like and improves inter-rater reliability. One method to develop a rubric is to define only the maximum possible outcome, then when applying the rubric, score each candidate according to how close it comes using a Likert scale. Another method is to define high, medium, and low outcomes and assign the category. The format doesn't matter; the rubric can be a descriptive document or a spreadsheet. The scale does not need to be evenly spaced; in fact, a nonlinear scale might be easier to use, such as only offering low, medium, and very high. This reduces the tendency to cluster programs in the middle.

Some guiding principles to keep in mind when using scoring rubrics:

- Keep it open. The process of developing a scoring rubric is as important as the results of its use. For the results to be trusted, the process must be trusted, therefore the process must be transparent and inclusive.

- Keep it simple. Resist any temptation to develop a sophisticated or highly precise rubric. No matter how precise or quantitative the analysis appears, most criteria are still based on qualitative information and professional judgment; precision is an illusion.

- Keep it positive. Define everything in the positive form to avoid pole confusion. For example, High or 5 when applied to a positive criterion such as Overall Benefit is clearly positive. When applied to a criterion such as Risk, is High Risk good or bad? One way to address that is to try to get everyone to remember that when talking about risk, High or 5 is bad. Alternatively, rephrase Risk as a positive Probability of Success so the scoring poles align.

In the following fictitious example, I present a case study of a university implementing institutional portfolio management. The story is compiled from my interviews of 20 university presidents and provosts who implemented program prioritization and my own experience implementing portfolio management at two different universities.

The Story of Waters State University

Waters State University is a comprehensive university in the upper Midwest. It serves the region's population of primarily traditional-age first-generation students, with undergraduate programs in liberal studies, education, business, and nursing, multiple master's programs, and a few recently opened doctoral programs. As with many of the public institutions in the Midwest, Waters State has struggled with a decreasing population of high school students and repeated cuts to their state budget allocation. In spite of the challenges and declining enrollments, Waters State has maintained high academic quality, launched an innovative general studies program, and built a reputation for sustainability research.

A few years ago, Waters State University hired Anthony Gofortt as chancellor following the retirement of the long-standing and well-regarded previous chancellor. Gofortt had ambitious ideas to advance the unsung quality of the institution to a position of national renown, but the severity of the budget cuts brought into stark reality the necessity of finding alternative means. Chancellor Gofortt launched a new strategic planning initiative, led by Provost Lance Wynns, as he investigated solutions to his resource problems.

As the strategic plan began taking shape, priorities emerged to increase diversity, expand academic programs in technology, sustain the widely acclaimed general studies program, and pursue the highest possible national ranking for sustainability research and campus practices. But the institution had still not found a way to fund any of the priorities. Over dinner with colleagues at a national conference, Gofortt shared his worries with his old friend Akeem Bashar, who told him of a newly proposed framework that might be useful to him, called Institutional Portfolio Management. Bashar also gave him contact information for the author and well-regarded scholar in the field, Antonia Williams.

Setting the Stage

Over the phone, Gofortt and Williams discussed a consulting engagement for her to assist Waters State with their Institutional Portfolio Management (IPM) initiative. Williams explained that she has studied this area for years, but IPM is a new framework that has not been completely tested. She was looking for a university to pilot it and participate as a case study. The chancellor agreed to the opportunity and listened carefully to her high-level plan of action.

Williams arrived for the first of many campus visits to hold a workshop on IPM for all faculty, staff, and administrators. The chancellor kicked off the meeting to explain why the campus community needs to do things differently, and the opportunity to participate in a newly developed practical framework for intentionally managing institutional performance metrics. Williams explained how IPM works, emphasizing inclusivity, transparency, and balance, and the firm belief that the campus must define and manage the process; she was there only as a facilitator and guide-on-the-side.

To start, Williams asked the audience what values the institution holds dear, and what groups should be involved in any large-scale change effort. As the audience shared ideas, she recorded them, displaying her notes on the large screen that was also streamed to office desks for staff and faculty who couldn't break away for the event. The audience suggested a shared governance steering committee with representation from all constituents. A volunteer monitored the remote participants to collect their viewpoints as well. With feedback collected and the campus community apprised of the coming initiative, the provost worked on convening the IPM Steering Committee and Williams returned home to polish up the plan before vetting with the group at their first of many weekly videoconference meetings. Over the next several months, she guided and supported the committee, enlisting a grad student to help with scribing and scheduling, and the university IT team to help with digital document sharing and remote tech support.

Communications

The first thing the Steering Committee did was to appoint a communications team, with expert support from the Marketing and Communications Department ("Marcomm"). The IPM Communications Team planned their communications to include a website, weekly news updates posted on the web and pushed through e-mail, a rumor hotline, and a series of scheduled press releases. With Marcomm's input, they quickly realized the promotional value of the IPM initiative in demonstrating to the board and legislature the proactive, transformative, and strategic approach the university was taking. Gofortt and Williams, along with the university's chief communications officer, held a conference call with the board, explaining the initiative and the expected outcomes. The board responded with cautious optimism.

Process Design

Next, the IPM Steering Committee appointed a process team to design and lead the process. While that team got started, the steering committee researched and selected institutional performance metrics to use post-process to demonstrate to constituents, the board, and the legislature the long-term results of their transformative change.

The IPM Process Team decided on two separate teams to gather information and evaluate academic programs and administrative programs, to merge eventually. They believed faculty should lead both teams to keep the emphasis on academic quality, whether directly through academic programs or indirectly through administrative support programs. They also made sure that staff were widely represented on both teams, then decided to convene the teams to help design the process.

The expanded Process Team decided on a single set of general evaluation criteria for both teams — alignment, value, and risk — as it would be easier to merge the two sets in the end, but each one was detailed differently for academic versus administrative programs. As they worked, the Process Team members continually checked in with constituents, sharing their progress and incorporating feedback.

The Process Team moved on to develop a workflow for both the academic and administrative Process Teams: discover (gather information), assess (categorize the programs according to the information), reallocate (make decisions about the programs), and evaluate (determine and report on the success of the process and the outcomes).

The first challenge for the Process Team was to determine what constitutes a program. Certainly it meant every major, minor, certificate, or other official stamp of academic completion, but what about classes that served multiple majors without being a distinctive major themselves? And what about administrative programs — was HR one program, or should it be broken into multiple programs such as one for Recruiting and one for Compensation? They discovered as much art as science to this part of the process and developed lists that they vetted with constituents until everyone was fairly comfortable with the programs named. They made sure to include new programs suggested by the priorities of the strategic plan.

The second challenge for the Process Team was to identify the information they would need about each program to make informed decisions. Here it became important to distinguish between academic and administrative programs. Even though the general criteria were the same — alignment, value, and risk — the details differed between the two. For example, historical value was often a benefit of an academic program but had little meaning for administrative programs, although administrative programs might have strong alignment to strategic priorities such as student diversity. Each team developed a glossary to define the general criteria for their purposes, then worked with Institutional Research (IR) and Finance to confirm they could obtain the information needed. In some cases, the effort to obtain desired information was too burdensome, and they selected proxy information instead. For example, calculating the cost for each program to use the campus network was impractical, so the total cost of network operations was estimated, then divided and attributed to the program based on headcount.

As the Process Team developed and vetted the process, they had many debates about the kinds of information needed and the lack of easily obtained but meaningful data. Constituents realized that stark decisions would be made based on the data provided, so the data included became politicized and polarizing. The chancellor and the provost realized that constituents were getting bogged down in data debates and had to move on, somehow. The Steering Committee suggested consensus ground rules: (1) You won't always agree, so (2) Can you support it? Or, (3) Can you live with it? (4) Because, we have to find a way to live together, inclusive of our disagreements. The ground rules helped move everyone along.

Finally, the Process Team published the process design and started the academic and administrative teams down the path.

Discover

As forewarned by IR, the biggest challenge was getting reliable data: the information system wasn't designed to keep track of the kind of program-level information they needed. It became a struggle for the IR office to find and prepare data in a usable format. The process teams and the IR office lost time in the schedule but persevered, helped by commiserating over the suddenly legacy information systems and the need for higher education to develop more robust business intelligence.

To help with the discovery, each program was assigned a program manager to shepherd the program through the process, someone not affiliated with the program but who understood it. The program manager was responsible for keeping the program information vetted, updated, public, and on track, working closely with the program affiliates. For each program they included the current costs, space, and technologies needed to operate the program, as well as the additional resources needed to reach goals, if any.

Assess

After six challenging months the university had an inventory of programs and information compiled in a web-hosted database constructed by the IT team. Guided by Williams throughout that time, the Steering Committee monitored and reported progress to the chancellor's cabinet while the Communications Team kept the campus updated on progress.

To start the assessment phase, the academic and administrative process teams categorized the programs in investment buckets: invest, maintain, reduce, eliminate. The Steering Committee decided to create a new team to run the assessment, also led by faculty with broad representation but now including external stakeholders to give input into regional strategic needs for higher education.

The Assessment Team combined the academic and administrative programs and ran the calculations to find out how much money could be saved by eliminating or reducing programs. Was it enough to cover maintaining and investing?

Nope. Disappointed but not surprised that their work just got harder, they belatedly realized that cash flow mattered, that programs couldn't be eliminated or even reduced overnight, and that new programs would start up slowly with uneven investment rates. The Assessment Team, after getting the Finance department to create a simple template, asked the program managers to develop rudimentary cash-flow statements. They also asked the program managers to develop a Reduction Plan and an Elimination Plan outlining the steps they would take if a program was reduced or eliminated, no more than one page. Maybe that would inform the cash-flow statements or indicate something that could be outsourced. The program managers and program affiliates were not happy with that request, referring to the plans as the Suffer or Die Plans. Ouch.

Williams came back onto the frontline, visiting campus for a couple of weeks. She met with numerous constituents, listening to their concerns and thinking about ways to address those concerns and help those constituents through an admittedly challenging process. She reflected that it was the secret mission of every organizational unit to preserve itself. How could she help Waters State overcome this dilemma?

Williams advised the Assessment Team to create some what-if scenarios, experimenting with investing in fewer programs, reducing some maintained programs, eliminating more programs, to come up with a few scenarios that they thought would be reasonable if still painful. They did so and published the scenarios across campus, then convened multiple campus-wide meetings to explain them.

Following those sessions, the Assessment Team gathered input by holding poster sessions, with each scenario visually and descriptively portrayed on a poster. The campus community was invited to attend and vote for scenarios with stickers or comment using sticky notes. The Steering Committee, Discovery Teams, and Assessment Team staffed the poster sessions for over a week, answering questions and collecting feedback. They summarized and published the feedback, and adjusted the scenarios based on the information collected.

Then they held another poster session and did the same all over again, this time with fewer scenarios. One of the scenarios was "Do Nothing" — eliminating no programs but also making no new investments. The campus seemed pretty evenly divided among the three remaining scenarios.

Reallocate

The Steering Committee realized they needed a way to make the final decision. After much discussion and several meetings, they convened a campus town-hall session and explained the dilemma and the need for a decision strategy to choose the final path. They offered three general decision strategies: (1) The chancellor and his cabinet could choose the scenario; (2) the campus could vote on the scenario, with the decision going to a probable plurality rather than a majority; (3) they could bring in outside stakeholders, such as legislators, board members, or consultants, to make the decision.

Faculty Senate leader Mark Sparks jumped up to make an impassioned speech, saying (in sum):

"External parties don't understand higher education and should not control our destiny. Further, a campus vote will result in a plurality, not a majority, meaning the majority will be dissatisfied. We hired the chancellor to lead the campus through difficult times, and he has executed an unusually participatory and evidence-based decision process, for which he should be commended. We have gone through a comprehensive strategic planning process to take us into the future, grim as it may be financially. We have no choice but to make cuts, and at least through this process we have all had a voice in the decisions. There is no ideal scenario acceptable to all until the legislature turns over (get your vote out!), but at least each scenario is acceptable to many. It's the chancellor's job to make the final decision with the advice of his trusted colleagues."

With that, the campus town hall ended. Williams wondered what the final decision would be.

Deeply concerned with the weight of the pending decision, Chancellor Gofortt spoke with each of his cabinet members in private to get their input; like the campus community, they also disagreed on the best scenario. Seeking counsel, the chancellor called his old friend and mentor Akeem Bashar, who wisely did not give him answers but asked him question after question. Finally Bashar said, "Trust in the process, my friend. Because of the process, any decision you make is as good as a decision can be."

With renewed confidence, the chancellor announced his decision the following day. The Finance department began the tedious process of redesigning budgets in response; the Facilities and IT departments stared at their previous strategic plans and accepted that they had to change their entire orientation from expense categories to program alignment; and the program managers looked glumly at their Reduction and Elimination Plans, which now were reality. In spite of the exhaustively inclusive and transparent process, surprised constituents flooded the chancellor's office and inbox with their concerns. The Communications Team, with Marcomm advice and support, jumped into action with messaging both internal and external.

Evaluate

Over the din of reaction to the chancellor's decision, the Steering Committee convened an Evaluation Team to design and execute evaluation of the process and the outcomes, which Williams stressed were two different things. The Evaluation Team developed a survey to assess constituent satisfaction with the process and their perception of its effectiveness. The team then developed a plan for recurring review and recalibration of the portfolio of programs, in a scaled-down process that would update the program information, goals, and requirements, as well as the budget, technology, and space plans. They asked Finance, IT, and Facilities to develop strategic plans oriented to the portfolio of programs and the evaluation schedule, which likewise aligned with the strategic plan. As part of the evaluation plan, they incorporated annual review of the institutional performance metrics selected at the beginning of the process. As had become customary on campus, they vetted and published the annual evaluation plan. The wheels were in motion for ongoing evaluation and management of the institutional portfolio.

Reflections

Some months later at a national conference, over dinner with Gofortt and Bashar, Williams reflected on the process and all that she had learned from it, noting the adaptations developed to make it work for their culture. She thanked the chancellor for the opportunity to work with Waters State University as her case study. He, in turn, was delighted with the outcome and shared his hopes that The Process, as they had come to call it, would help institutions of higher education break the iron triangle with intention and positive effect. Said Bashar, raising his glass with a smile, "That's right, my friends. Trust in The Process."

Conclusion

Pressure to demonstrate improved institutional performance will not decrease anytime soon. Other industries face similar constraints and pressures and have taken dramatic steps to address performance and satisfy stakeholders. The stakeholders of higher education may not be satisfied until they see similar transformative change in our institutions. But, simply demonstrating intentional improvement management enables us to better articulate our academic mission and demonstrate our value.

Unfortunately, the objectives demanded — improved access, cost, and quality — conflict with one another. To increase one requires a reciprocal decrease in another. The best strategy is to recognize the competing objectives, choose the right balance for the institution, and manage resources accordingly.

The framework of institutional portfolio management can facilitate that strategy to address immediate expectations and break the cycle of fragmentation and realignment seemingly beyond the control of institutional leadership. Setting goals in the context of public expectations and demonstrating effective management to reach those goals illustrates both the constraints and the institution's performance within those constraints. Higher education technology leaders who understand the challenges facing their institutions, who recognize the confluence of portfolio management and program prioritization, and who understand how to apply the best practices of each, can support their institution in demonstrating continuous performance improvement.

Notes

- United States Department of Education, "A test of leadership: charting the future of U.S. higher education," 2006.

- John Immerwahr, Jean Johnson, and Paul Gasbarra, "The Iron Triangle: College Presidents Talk about Costs, Access, and Quality," National Center Report #08-2, 2008.

- John. Daniel, Asha Kanwar, and Stamenka Uvalic-Trumbic, "Breaking higher education's iron triangle: access, cost, and quality," Change, Vol. 41, No. 2 (2009): 30–35; and Immerwahr et al., "The Iron Triangle."

- Project Management Institute, The Standard for Portfolio Management (Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2008); and Parviz Rad and Ginger Levin, Project Portfolio Management Tools and Techniques (New York: International Institute for Learning, 2006).

- Ibid.

- Robert B. Archibald and David H. Feldman, "Why Does College Cost So Much?" (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Patricia J. Gumport, Sociology of Higher Education: Contributions and their Contexts (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

- Robert Birnbaum, How Colleges Work (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1988); James J. Duderstadt and Farris W. Womack, The Future of the Public University in America: Beyond the Crossroads (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003); and Peter D. Eckel, "Decision Rules Used in Academic Program Closure: Where the Rubber Meets the Road," Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 73, No. 2 (2002): 237–262.

- Robert C. Dickeson, Prioritizing Academic Programs and Services: Reallocating Resources to Achieve Strategic Balance (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1999), and Prioritizing Academic Programs and Services: Reallocating Resources to Achieve Strategic Balance (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010); and Anne Milkovich, "Academic program prioritization among institutions of higher education," paper presented at the Association for the Study of Higher Education, St. Louis, MO, 2013, and "How Incremental Success Slows Transformative Change and Integrated Planning Achieves It," Planning for Higher Education, Vol. 44, No. 2 (2016): 1–9.

- Milkovich, "How Incremental Success Slows Transformative Change."

- Ram Kumar, Aajjan Haya, and Yuan Niu, "Information Technology Portfolio Management: Literature Review, Framework, and Research Issues," Information Resources Management Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3 (2008): 64–87.

- W. A. Daigneau, "Portfolio Based Management," Facilities Manager (November/December 2010): 20–25; Lex Donaldson, "Organizational Portfolio Theory: Performance-Driven Organizational Change," Contemporary Economic Policy, Vol. 18, No. 4 (2000): 386–396; Vernon B. Harper Jr., "Program Portfolio Analysis: Evaluating Academic Program Viability and Mix," Assessment Update, Vol. 23, No. 3 (2011): 5; Dragan Miljkovic, "Organizational Portfolio Theory and International Not-for-Profit Organizations," Journal of Socio-Economics, Vol. 35, No. 1 (2006): 142–150; and Justin M. Reginato, Project and Portfolio Management in Dynamic Environments: Theory and Evidence from the Biopharmaceutical Industry, PhD thesis (3190854 Ph.D.), University of California, Berkeley, 2005.

- ISACA, COBIT 5 (Rolling Meadows, IL: ISACA, 2012); and Project Management Institute, The Standard for Portfolio Management.

- Dickeson, Prioritizing Academic Programs and Services (1999 and 2010).

- Milkovich, "Academic Program Prioritization."

- Ibid.

- Milkovich, "How Incremental Success Slows Transformative Change."

- Robert Cope and George Delaney, "Academic Program Review: A Market Strategy Perspective," Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, Vol. 3, No. 2 (1991): 63–86; Dickeson, Prioritizing Academic Programs and Services, 2010; V. B. Harper Jr. "Strategic Management of College Resources: A Hypothetical Walkthrough," Planning for Higher Education, Vol. 41, No. 2 (2013): 158+; Project Management Institute, The Standard for Portfolio Management; and Rad and Levin, Project Portfolio Management Tools and Techniques.

- Dickeson, Prioritizing Academic Programs and Services (2010).

Anne Milkovich is the chief information officer at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh, with 10 years of experience in higher education and over 25 years of experience in information technology management and consulting. She has a doctorate in Education with research in the domain of institutional performance and portfolio management. Her education includes an MBA and professional certifications in Governance of Enterprise IT, Project Management, and Human Resources.

© 2016 Anne Milkovich. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.