Key Takeaways

- Chief information officers expect a shift within the next five years, from primarily managing infrastructure and technical resources toward managing outside relationships.

- Increasing acceptance of increasingly available cloud technologies and services allow redefining higher education's approach to enterprise IT.

- Four institutions explain their cloud strategies as developed in response to enterprise challenges and share their lessons learned.

[This article is the first in a series that presents case studies related to important themes within enterprise IT.

- Developing Institutional Cloud Strategies

- The Impact of Cloud Implementations on Budget Strategies

- The Dean’s Information Challenge: From Data to Dashboard

- Cloud Migrations: An Opportunity for Institutional Collaboration

Each article in the series begins with a scenario that provides context for the theme, followed by several case studies.]

The evolution and maturation of cloud technologies has tipped enterprise IT into a transitional stage: A 2015 EDUCAUSE study found that CIOs expect a significant shift in focus within the next five years, away from managing primarily infrastructure and technical resources and toward managing vendors, services, and outsourced contracts.1 This implies that the increased availability and acceptance of cloud technologies and services will create the opportunity to redefine the way we focus enterprise IT work.

Scenario

Sara has just begun a new job as CIO at her institution, arriving when the CIO position has been vacant for some time. IT at her new institution remains an on-premises shop, although Sara knows that some areas (facilities, HR, continuing education) have engaged cloud vendors without input from IT. She has heard that many faculty and staff use Dropbox for sharing large files internally and externally, and that many faculty have started their own Google sites for class collaboration outside of the learning management system. She has also heard of one instance where a selected vendor went out of business and the department lost data in that system.

Some of the administrators on the president's cabinet are wary of putting university data in the cloud. Others say, "Let's move everything to the cloud!" And although some of Sara's staff are eager for new challenges and new ideas, others come to her worried about increased risk and loss of control.

Sara plans to address these issues by developing a strategy for enterprise IT that includes cloud technologies and services as part of the portfolio. She knows that an important part of her strategy will be cloud governance that includes stakeholders from across the institution. The new strategy will highlight IT as more than just a service provider, but as a partner and broker for IT-related services.

This article looks at how four different institutions have reacted to similar situations through the development of cloud strategies.

The California College of the Arts

Mara Hancock, CIO and VP-Technology

The California College of the Arts (CCA) is a small (1,900 FTE) nonprofit art and design college located in the Oakland/San Francisco Bay area, which is a global hub for technological and cultural innovation. CCA offers courses in areas such as digital crafts and fabrication, an MBA in Design Strategy, animation, comics, and more. While primarily a residential college, CCA has several low-residency graduate programs and increasingly is adding online and hybrid courses. Our first MOOC is being offered on the Kadenze.com platform, which was developed specifically for the creative arts.

The Challenge

When I arrived at CCA in fall 2012, it was clear that several big challenges faced the college in regard to our core IT infrastructure and services. I spent three months meeting with faculty, staff, and students to understand their perception regarding the key challenges and opportunities for technology at CCA. Those meetings identified six key design challenges that people wanted technology to meet:

- Connect more people

- Help tell the CCA story

- Integrate into the academic experience

- Create a more seamless user experience

- Support the key business of the college to be more effective and efficient

- Redefine the teaching and learning experience

Three of the six — 2, 4, and 5 — were directly tied to our enterprise IT infrastructure and services. The key challenges we faced were:

- Distributed platforms: Core enterprise resource planning (ERP) functions such as HR/payroll and student recruitment were being delivered across multiple platforms chosen solely from the business unit/back-office perspective. Not supported by our central IT unit, these platforms had little oversight to ensure requirements were met, data was secure, or that end-user and decision-maker expectations were met (there was a severe lack of analytics).

- Lack of data integration and integrated business processes: These distributed systems didn't integrate with the core ERP, which housed Financials and Student Records (and was supported by central IT). The lack of integration meant that data was being moved (when it was being moved) manually, and users had to leap between interfaces. The campus community, highly aesthetic and attuned to the user experience, was extremely unhappy with the current ERP system and the ensuing fractures that developed between it and other systems.

- Limited service support: One of the largest challenges was support for services following their launch. We were good at getting the server or app up and running, but had little direct support or business analyst support once we went live. Clearly, either the team had to grow, or the activities needed to change. Or perhaps both, within reason and funding capacity. In addition, we had limited project management knowledge or ability on staff, resulting in scope creep, project extensions, and limited visibility or communication.

- Substantial risk: At a small college, staff inherently must wear multiple hats; however, CCA IT had severe silos, where the loss of one individual could compromise the ability of the organization to function. The lack of data governance, an understanding within the IT organization regarding where critical data resided, or how it was being managed created a large security risk.

- Current ERP not up to the task: The system we were on was already highly customized and behind on key updates. We researched options within the system such as new modules, but none were compelling enough to merit the costs or to lure the functional owners of the other systems to engage on a single platform. In addition, the code base on the ERP and many of our distributed systems was old. It had been patched and upgraded and hacked… but it wasn't going to get any better.

In short, I needed a system that the small CCA IT team could support, that would meet the needs of the back office while providing new value for the broader set of stakeholders by creating an integrated set of fluid user pathways, and that would provide key analytics and support. The timing was good — emerging cloud services took advantage of new technology and new user experience paradigms, so we had some options to explore.

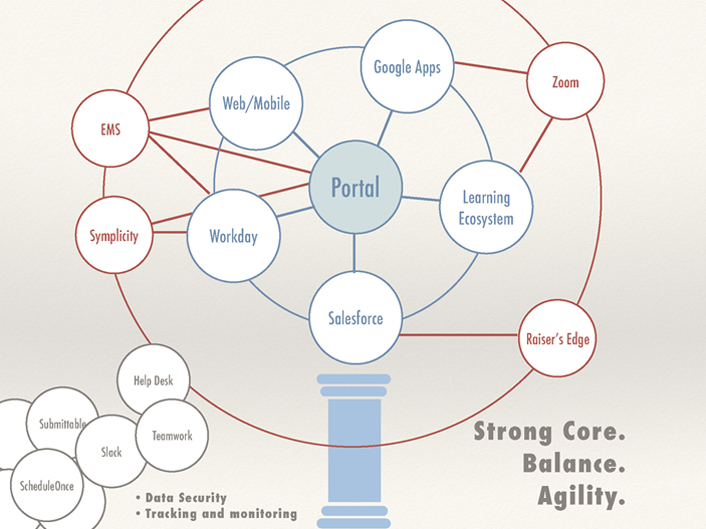

We developed what we call the "strong core" strategy. The "Core Six" puts a set of systems at our center, which means the most significant portions of our resources attend to these Core Six platforms. The second ring consists of best-of-breed applications — we prefer in-the-cloud or software-as-a-service (SaaS) with strong application program interfaces (APIs) — which cover areas that the core systems don't reach but are necessary for the enterprise. On the outer edges, we allow departments to adopt cloud-based tools to meet their department-specific needs. Central IT provides a security review and a level of portfolio management.

At the center is the portal (in development now), which helps not only to bring some of the core data together in an integrated interface but also to address our number 1 and number 2 design challenges, Connect More People and Tell the CCA Story. See figure 1.

Figure 1. Support centered around the portal

About six months after my arrival, we hired a new CFO. As she engaged and developed her own assessment of the organization, we aligned our strategies and partnered to establish a pathway forward.

We began where we had the least effective systems and biggest gaps: HR/Payroll and Student Services. By working with Salesforce (Student Services) and Workday (HR/Payroll), we were able to quickly implement solutions. In the process we reimagined IT staffing as well. We created several key positions, one being the director of the Project Management Office, which helped bring key project management tools to the college as well as to manage these large implementations.

Lessons Learned

Despite feeling like we were communicating constantly, it was never enough. As we developed strategy that I shared with my peers on the president's cabinet, I assumed that the other members would communicate this out to their teams. This really wasn't good enough to build buy-in and initially set off more rumors than truths.

Some of the things we did to address this were:

- Formed a new committee, the Administrative Managers User Group, chaired by the director for Administrative Computing, specifically to engage around the technology roadmap. One beneficial surprise coming from that group is that cross-cutting business process and policy issues often arise, frequently independent of technology.

- Held a timeslot at the college's all-staff meeting in which to update folks on the technology strategy and roadmap along with other things.

- Instituted a change management lead on each project.

- Recrafted an internal IT role to help support the development of documentation and training.

The network has become increasingly important in maintaining connectivity to the core platforms. We have completely redone the wireless infrastructure on our Oakland campus and are planning to upgrade our San Francisco campus this year.

Security concerns change. Rather than solely securing our data center and local network, we have had to build new protocols for assessing risk with the cloud-based platforms. As phishing efforts and front-door attacks increase, we are spending a good deal of effort ensuring that we create better locks, such as multifactor authentication and deeper auditing tools.

Over the course of the three years of developing the strategy and implementing its first stages, we have recrafted the IT organization to support a more cloud-based strategy, with new staff bringing project management, business process, and data integration skills. We will increasingly be less about supporting the servers and more about supporting the business.

Developing a Cloud Strategy at the George Washington University

Larry Legge, Director, System Engineering, Division of Information Technology

The George Washington University is a private, coeducational research university located in Washington, D.C. It comprises three campuses — Foggy Bottom and Mount Vernon in Washington, D.C., and the Virginia Science and Technology Campus in Ashburn, Virginia — as well as several graduate education centers in the metropolitan area and Hampton Roads, Virginia. The university is the largest institution of higher education in the District of Columbia.

The Challenge

The evolution of a cloud strategy at the George Washington University (GW) initially began with the university's migration from an in-house e-mail platform to Google Mail/Apps in 2008. Since then, the university's strategy has evolved due to a number of factors, including successfully moving services to the cloud in an established framework, funding constraints, a desire to focus on core services, and a reduction of the university's data center footprint.

One of the goals of university IT is to align with the types of services that students, faculty, and staff use before they arrive on campus and expect to use while they are here. Understanding that GW is not an expert on every system, the university has begun to look for opportunities where it makes more sense to go with a cloud provider. Cloud providers can typically provide access to new functionality more quickly than what can be built on premises.

However, not every service can be moved to the cloud. As services come up for lifecycle renewal, they are evaluated for whether the university can consume that service in a cloud-based model. An initial assessment takes into account security practices (the type of data being stored in that system) as well as whether that particular system can accommodate the type of customizations needed.

Governance over cloud strategy at the university level also allows for input and consensus. It allows IT to serve in a brokerage capacity (looking for opportunities where similar capabilities are needed across the university and "brokering" a deal that will benefit the university population). One of the key objectives of this model is to meet the demands of the larger university community while driving financial efficiency.

Lessons Learned

While GW has seen a number of efficiencies gained from moving to a cloud model, other areas still remain focal points. Socialization of the overall strategy for moving services to the cloud is needed, and the governance committee must continue to evolve. Below are some additional lessons learned from the GW experience

No "One-Size" Model: GW is a large, private, research institution with a decentralized IT model. For GW, making a global decision to move everything to the cloud was not possible; often collaboration throughout the university is necessary, and every service must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Some of the information that helps drive decision making is whether access to new functionality is faster than what is possible to build on premises, whether a common enterprise-grade service that requires no specialization or customization is available, and whether needs are met right out of the box. In addition, as a private institution, GW is allowed more flexibility in its strategy, while other state schools may have additional oversight.

Vendor Management: Vendor management plays a significant role in designing a cloud strategy. GW has a team focused on contract management, including the review and negotiation of contracts with vendors. Vendor management in an interrelated environment with multiple providers and on-premises and cloud-based services is a critical component. Our maturity plan includes moving beyond simple service-level commitments to measurable, repeatable, and consistent service levels. Additionally, working from a holistic view of the vendor and performance we can leverage strengths and present focused service improvement requests. An exit strategy also needs to be considered when entering into a contract with a cloud provider.

Acceptance of Risk and Culture Change: These two factors will drive speed of adoption. In order to move to a cloud model, we must factor in a culture shift at the university to both move more services off premises and accept more risk. Overall changes in this direction may alter staffing models. In turn, this provides an opportunity to repurpose funding.

GW is proceeding along three parallel paths:

- We are leading with a "Why not cloud?" mindset in response to new technology and integration demands from our community. This is embodied in our guiding architecture principle: Rent before Buy, Buy before Build. The preference is to acquire a capability as prepackaged as possible, for the right value and right risk profile.

- We want to proactively repackage some of our legacy services in more cloud-friendly environments to prepare them for a new paradigm. Examples of this are our current internal Oracle Solaris server virtualization efforts and business process analysis for next iterations of enterprise resource planning (ERP) system versions and platforms. The intent is to establish a glide path for these types of services and a shift in delivery method.

- We are implementing plans for the rest of our service portfolio. Many of these services are not as cloud-ready and don't have as apparent a glide path to cloud provision. We are undertaking an analysis for a shift to an infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS) model. We recognize that there will still be a need for a services footprint on premises, but that it should and will be dramatically smaller. We intend to approach future decisions on delivery model with the same type of objective analysis.

We intend to continue to partner with providers that help us with scale, risk mitigation and our transitions. We intend to continue to look to subscribe to external services and leverage consortia that allow for attaining the right value from migrations or implementations, and alignment with our risk profile objectives.

Acknowledgments

Kara Gillespie, Communications and Marketing Associate; Christina Griffin, Director, Project and Portfolio Management; William Koffenberger, Director, Service Management; and Edward Martin, Deputy Chief Information Officer, The George Washington University.

University of Hawai'i System

Bill Wrobleski, Director, Technical Infrastructure

The University of Hawai'i (UH) System includes 10 campuses and educational, training, and research centers across six different islands, with nearly 60,000 students. Our academic offerings range from certificate and vocational through doctoral programs. Our unique position between east and west, in the middle of the Pacific, creates opportunities for international leadership and influence. Asia/Pacific expertise permeates the university's activities.

The Challenge

In 2014, UH completed the construction of a state-of-the-art Information Technology Center (ITC) to house the system's central information technology organization, as well as an 8,000 square foot data center to serve as the home of the university's mission-critical systems. The ITC is located on the system's flagship campus, UH Mānoa in Honolulu, and was designed to minimize the risk that hurricanes, floods, or other disaster scenarios would disrupt the university's IT systems. UH's unique geographical location made it a priority for the university to build this type of facility. Of course, even with a new, well-hardened facility, establishing an effective disaster recovery alternative was critical, so UH implemented a multiyear disaster recovery project to put in place appropriate recovery technologies and processes.

UH has developed a cloud computing strategy that is summarized in this sentence: "UH will adopt cloud computing services on a case-by-case basis taking into account functional, financial, and logistical factors." As a result, when we considered various approaches to addressing our disaster recovery needs, we included the review of cloud-based alternatives. We concluded that the most cost-effective approach involved a combination of our own off-site backups with a cloud infrastructure service.

The UH Disaster Recovery Project included the following work:

- Establishing off-site disk-based backups for all enterprise systems. Nightly backups of all applications are located in a second data center (also located on O'ahu).

- Contracting with a cloud provider for virtual servers and storage services. UH chose a vendor with resources in the same data center as our backups.

- Re-architecting key support infrastructure to leverage cloud services (e.g. authentication and web content services).

- Developing and testing recovery plans for key UH enterprise applications.

The UH recovery process consists of recovering applications and databases from our off-site storage to cloud-based virtual servers. The project has completed most of the setup work, but continued testing and refinement is underway. Once fully complete, this approach should allow UH to achieve a recovery time objective (RTO) of two to five days and a recovery point objective (RPO) of 24 hours.

Lessons Learned

Cloud services are cheap when you can turn them off. When you buy hardware and software, you have to pay for it whether or not you use it. In the cloud, pricing models are more flexible and take into account your utilization of the resources. Therefore, it is possible to establish a fairly robust disaster infrastructure without large one-time or ongoing expenses. Large expenses are only seen in the unlikely case that one actually declares an emergency and must fully mobilize the infrastructure. If we did not leverage cloud services, UH would have had to purchase a significant amount of infrastructure and contract for corresponding data center space. Leveraging cloud services allowed UH to achieve the same goals at a fraction of the cost.

For this reason, disaster recovery is a good candidate for an early cloud project for many institutions.

Cloud services can't make a complicated problem simple. From a high-level perspective, the UH disaster recovery model may seem simple or easy to understand, but the actual implementation involves a lot of pieces and complexity. Cloud services helped enable our vision, but they didn't eliminate our need to work through many technical details. Delivering an effective disaster recovery infrastructure is always complicated, and the cloud does change that. Other institutions that choose to pursue a similar approach should not underestimate the effort to design, build, and test their solution.

One size doesn't fit all. UH's cloud-based disaster recovery model takes into account many of our unique needs. Specifically, we needed to build out an off-site backup solution for our systems and had a prearranged agreement with a local data center provider to house some of our equipment. As a result, when it came to designing our disaster recovery infrastructure, it made the most sense for us to work with cloud vendors that were housed in the same data center as our backup storage on O'ahu. Our final design and our choice of vendors might not be appropriate for other schools, but our general approach could be used at many other institutions.

Small steps help form the foundation for larger ones. UH has adopted an opportunistic cloud computing strategy. We are not in a rush to move to the cloud, but we do want to take logical and appropriate steps forward. Our team found this project to be a practical introduction to the benefits and challenges of using cloud services — a nice step forward for our organization with regard to the cloud — and now we're ready for our next step.

Yale's Journey to the Cloud

Susan Kelley, Chief Technology Officer, Information Technology Services

Founded in 1701, Yale University has long recognized the value of cloud computing! Yale makes its home in the heart of New Haven, Connecticut. Comprised of Yale College, Yale Graduate School of Arts & Sciences, and 12 professional schools, Yale has close to 12,400 students and 4,400 faculty members. Yale has both a central Information Technology Services organization (ITS) and distributed IT partners who support schools and departments.

The Challenge

For many years we have selected cloud services, especially software-as-a-service (SaaS) cloud-hosted applications, when they best fit the university's requirements. In parallel we also support robust on-premises data centers. Our campus data centers developed organically across several decades. Only a few years ago we had three administrative data centers and one tape location on central campus, and an additional data center and tape location at our West Campus location eight miles away. We needed to manage power and cooling distribution and reliability; security; building controls; and the capital investment lifecycle to support all that infrastructure for a total of six locations.

Our experience with SaaS offerings and initial forays into cloud-based platform-as-a-service (PaaS) and public cloud infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS), especially by our IT partners on campus, have been successful. These successes provided clear evidence that we can better align our investments in IT to the university's mission by accelerating our journey to the cloud. We chose to anchor Yale's journey to the cloud through two objectives: reduce our on-premises data centers, and align with Yale's sustainability vision.

As we made significant progress in virtualizing physical servers (greater than 80 percent) we saw an opportunity to reduce our data center footprint. Since 2012, we have reduced our administrative data center footprint by 45 percent, from roughly 15,000 square feet to 8,300 square feet. This reduction in data center space frees us from what would have been significant lifecycle capital investment. Yale ITS is looking to the public cloud to continue efforts to reduce our data center footprint further.

The Yale ITS Infrastructure Engineering team has carefully managed the power usage effectiveness (PUE) in our data centers. PUE is the measure of how efficiently a data center uses energy. Strong evidence demonstrates that large public cloud IaaS providers are significantly more efficient in power usage than the typical enterprise data center. Much of this efficiency is accomplished via power and cooling infrastructure required to support compute and storage capacity.

The annual Uptime Institute survey reports the average enterprise data center PUE to be 1.7. This compares to a Google self-computed and well documented PUE of 1.12. Ample backing supports Yale's confidence in making progress on our sustainability vision [http://sustainability.yale.edu/planning-progress/areas-focus/energy-aof] if we look to the public cloud to further reduce our data center and energy consumption footprint. Yale is committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions 43 percent below 2005 levels by the year 2020.

Yale ITS developed a strategy to migrate to public cloud providers to meet this objective and others. We recognize that Yale servers in the cloud will use energy, but they will be managed in a more energy-efficient environment than we would be able to achieve on campus. Yale's information technology community is committed to do its part in reaching the university's sustainability goals.

Lessons Learned

In advancing our goals we:

- Developed a cloud business case that shows in detail how we can invest lifecycle refresh dollars (for data center infrastructure, servers, storage) in cloud services over time and reduce on-premises investments while we grow in the cloud.

- Formed a Cloud Working Group reporting to the Yale Technology Architecture Committee (a Yale IT governance committee). The working group is developing principles and guidelines for determining whether to target IaaS, PaaS, or SaaS for specific applications and technologies. The working group will also determine criteria for selecting cloud vendors. Many of our IT Partners are working with central IT to develop these guidelines together and to share experiences. Some of our IT partners embraced cloud PaaS and IaaS services early on and have a great deal of knowledge and experience to offer.

- Positioned our Infrastructure team to focus on self-service capability for developers and system administrators to provision IaaS and PaaS services in the cloud.

- Began conversations around what elements of DevOps make the most sense for Yale to focus on first, and how we can apply a more dynamic application management strategy to our portfolio.

Associate CIO of Infrastructure Services Vijay Menta is enthusiastic about Yale's journey to the cloud:

"We will be able to deliver our services with greater agility, resiliency, and elasticity while we achieve our objectives to reduce data center footprint and improve overall power efficiency."

Yale's journey to the cloud will be a widely collaborative effort. We do not underestimate the work ahead to accomplish the journey but also embrace the significant benefits we expect to achieve.

Supporting the Institution's Business

As these four case studies illustrate, no one strategy will work for everyone. They also reveal that certain approaches should be considered across all strategies. The four examples suggest that cloud strategies are most successful when backed by a strong governance model, detailed communication process, renewed focus on security and risk management, and rethinking of the work of IT so that it effectively supports the business of the institution. The lessons learned by The California College of the Arts, The George Washington University, the University of Hawai'I System, and Yale University can help other institutions bypass problems and achieve positive results as higher education moves more of its business to the cloud.

Note

- D. Christopher Brooks, The Changing Face of IT Service Delivery in Higher Education. Research report. Louisville, CO: ECAR, August 2015. Available from http://www.educause.edu/ecar.

Mara Hancock is chief information officer and vice president, Technology, at The California College of the Arts.

Larry Legge is director of System Engineering, Division of Information Technology, at The George Washington University.

Bill Wrobleski is director of Technical Infrastructure for the University of Hawai'i System.

Susan Kelley is chief technology officer, Information Technology Services, at Yale University.

© Mara Hancock, Lawrence Legge, William Wrobleski, and Susan Kelley. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0 license.