Key Takeaways

- Year two of Case Western Reserve University's Active Learning Fellowship program supported the first year's evidence of success in using active learning techniques in active learning classrooms.

- Unexpectedly, active learning techniques applied in large classes in regular classrooms proved unpopular with students, as expressed in surveys and focus groups at the end of the semester.

- The challenges teased out of the data indicated additional factors influencing active learning success and guided modifications to year three of the Active Learning Fellowship faculty selection process.

In fall 2013, researchers at Case Western Reserve University1 developed an active learning initiative, through which a group of 12 faculty members participated in a year-long Active Learning Fellowship (ALF). As a part of the ALF, these faculty members either created a new class or restructured a previously taught class to include active learning techniques with the goal of increasing student engagement and success. For the first year, these faculty were assigned, if possible, to one of two active learning classrooms (ALCs) that were optimized for collaboration within the classroom. Overall, student surveys and focus groups indicated that both teachers and learners benefited from and appreciated the active learning experience. We published the year one report, "Active Learning at Case Western University," a year ago in EDUCAUSE Review (January 26, 2015).

Feedback from students and faculty involved in the first year of the program aided in the development of two new ALCs that were used, in combination with the already existing rooms, for the 2014–15 ALF. Year two of the ALF provided generally positive and exciting results; however, we encountered new challenges that could prove problematic in the advancement and extension of active learning in the educational landscape.

Year 2 Project Goals, Context, and Design

Building off the success of the 2013–14 ALF, the Division of Information Technology Services (ITS) at Case Western Reserve University designed two additional ALCs. These new rooms shared many features with the classrooms from year one, but were adapted based on feedback from previous faculty and students. Both rooms employed a number of technologies not commonly found in CWRU classrooms, such as multiple large displays, collaborative work spaces, and flexible, reconfigurable furniture. Other features included inviting/modern colors and shared writing surfaces such as multiple whiteboards (both large and small) and writable walls. Please see figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Thwing 101 at Case Western Reserve University

Figure 2. Bingham 204 at Case Western Reserve University

As in year one, ITS conducted a year-long fellowship program to provide the resources and support needed to create active learning courses. Twelve faculty members were chosen through a competitive application process from a variety of disciplines, with both undergraduate and graduate courses included. Fellows (re)designed one of their classes using active learning techniques such as project- and problem-based instruction, collaboration, and formative assessment. They worked with ITS staff and other university partners (e.g., from the University Center for Innovative Teaching Excellence, UCITE) during a week-long intensive workshop in the summer. When possible, faculty taught their course(s) in one of the four ALCs. Some fellows could not teach in the spaces due to time or space limitations; these faculty were encouraged to use active learning techniques as much as possible in their traditional spaces.

The second year of the ALF evaluated the fellows' success according to the types of instructional methods used and amount of active engagement in the courses, as well as student satisfaction with instruction and technology.

Data Collection Methods

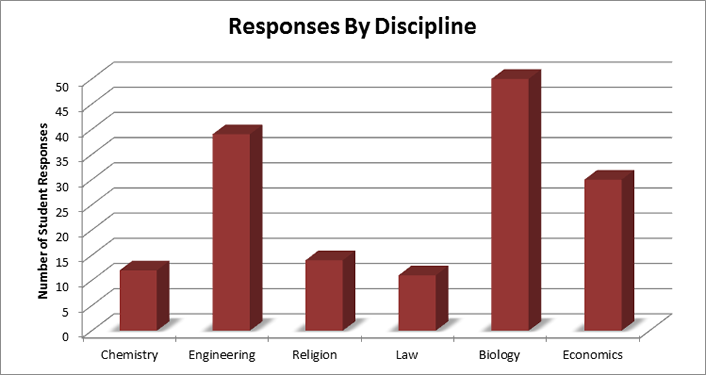

Data in this study were collected at the end of the semester via student surveys, student focus groups, and faculty interviews. Students from eight courses taught in ALCs were invited to take a survey administered in class (114) and online (43). In total, 157 students (146 undergraduate students, 11 Law School students) responded (see figure 3). Additionally, 125 students from two courses not taught in ALCs were also invited to fill out a survey. For the purposes of this article, responses will be looked at separately.

Figure 3. Breakdown of responses based on discipline for classes taught in an ALC

Data Analysis Methods

The survey data analysis used SPSS and Qualtrics software. Descriptive statistics were gathered in order to examine central tendency and variability of the dependent variables of interest. Furthermore, difference-of-means tests investigated potential differences between subgroups within the study (e.g., male vs. female, type of classroom used for instruction, etc.). Focus group data was organized and classified into nodes based on various themes (e.g., use of technology, engagement with material, etc.) using NVivo software.

Findings

In line with the findings from year one, when comparing their experiences to traditional courses, students in all classes taught by ALF faculty reported greater amounts of in-class and active group work, group projects, and interactions with peers regarding course-related content. These results confirm that the course manipulation succeeded; faculty members did include more active teaching methods.

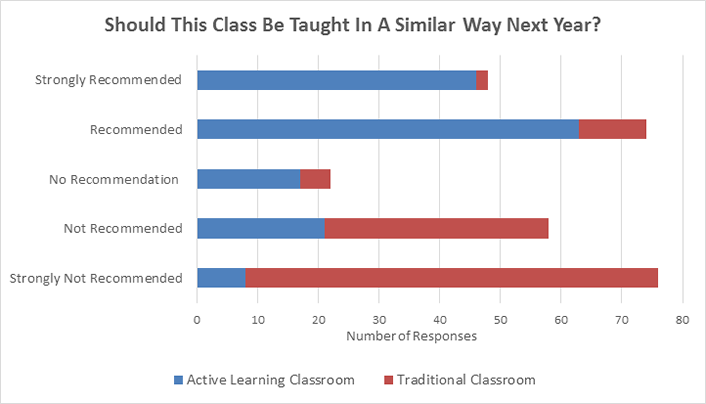

Also similar to year one, students in ALF courses indicated a relatively greater amount of active engagement compared to their other classes. Again, students taking these courses in an ALC reported an appreciation for active engagement, noting that active learning in these courses was valuable to them, increased their enthusiasm for the course, and positively affected their learning. However, students taking an ALF course in a traditional classroom reported a relative dislike for the active learning techniques used. This pattern continued when students were asked whether they thought the ALF course should be taught in a similar fashion in future semesters. Students who took a course in an ALC indicated the course should be taught similarly, whereas students in a traditional classroom indicated that it should not be taught the same way (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Student recommendations in ALCs vs. traditional classrooms

At first glance, these results seem to indicate that the type of classroom (traditional vs. ALC) has a major impact on student perception. However, looking more deeply into the situation reveals a complicated story about what promotes success with active learning.

Indices of Success for an Active Learning Course

Remember that only two courses were taught in a traditional classroom, compared to 10 classes taught in an ALC. This, in itself, limits the conclusions that can be drawn from the data. However, some interesting patterns emerged while exploring the differences between the more and less successful courses.

Class Size

In the ALF, the two classes that received negative reviews from students were larger classes (two sections of 50 students in one course and 200 students in the other course), whereas the 10 courses with positive reviews had an average of 22 students. Previous research had indicated that active learning can work in larger classes; however, it does present more challenges than in classes with fewer students. Though we had expected success with active learning even in the larger classes, this did not occur.

Although ALF members who could not use the ALCs did not successfully apply active learning techniques, this might not have resulted from the classrooms' limitations — other factors played a role as well. (Note that these faculty members received the same — or more — mentor support throughout the semester as the ALC classroom instructors.) Regarding class size, one student reported:

"I believe the class has too many students and [is] taught in too large of a room for active learning. I believe that for active learning to work successfully the student teacher ratio needs to be better."

Quality of Pre-class Activities

Students in the two less successful courses reported, via survey and student focus groups, that the pre-class activities (i.e., videos, readings) were not very helpful. Conversely, students in the other 10 courses generally reported a higher quality of background work prior to entering the classroom. This work made these students feel confident and prepared to learn the more difficult topics during class. One student said:

"I loved everything about how this course was taught… having the lectures online allowed me to watch them at my own pace, and to watch them multiple times. Because of these videos, the group work in class helped me master the concepts much better than I would have in a traditional class."

In-class Activities

Students in the less successful courses reported that the in-class activities were not well organized, that groups were poorly constructed, and that the activities did not match the corresponding content. The instructors were reported as being less involved and not as helpful/responsive during the in-class work. In the more successful courses, instructors were actively engaged with the groups and provided constant feedback regarding student performance. Two happy students stated:

"I like the in-class activities. They make me feel more involved and connected to the subject, especially with the case studies. It shows us how the information is all relevant and how we can apply it to the real world."

"I felt like I had to deal with the information we were learning on a deeper level — really work with it and discuss the nuances. Teaching others really helped my own understanding. I felt like this class genuinely mattered to my development as a student."

Instructor Variables

In the two courses with worse reviews, students reported that the instructor seemed ill prepared for class; made frequent mistakes when showing examples; didn't provide appropriate feedback for in-class work, homework problems, and/or exams; and provided an unclear syllabus for the course. Instructors in the other 10 courses were generally considered actively engaged, conscientious, and well prepared. Also, prior experience teaching the ALF-specific course was an important factor: Those who had taught the class previously experienced greater success. A student in a focus group from one of the less successful courses shared the following:

"Active learning is interesting; we aren't all used to it. I don't think it's a bad concept, but it was poorly executed. It would have been nice to have a bit more structure as to what we should expect in the course. There was a little bit of floundering due to a lack of a structured syllabus and a lack of feedback with our grades."

Conclusions

Based on two years of data, the indices of success in an active learning class at CWRU indicate that variables such as significant instructor experience in teaching the course, smaller class sizes, and type of classroom are all important. However, a smaller class with a well-prepared instructor who develops helpful pre- and in-class exercises that match course content would be a recipe for success in just about any good course.

Communication of Results

The results of the study were communicated to the faculty and administrators who had expressed interest in improving the quality of teaching at Case Western. Presentations were given at senior staff meetings and written summaries were provided to the stakeholders. Data have also been reported externally through two New Media Consortium presentations. Faculty also have reported data from their classes in various professional meetings and publications specific to their disciplines.

Influence on Campus Practices

The results of the first two years have provided evidence that the ALF successfully helps faculty achieve their instructional goals. Therefore, the ALF has been expanded to 16 faculty members for 2015–16. To provide a more personalized experience for each faculty member, we divided faculty participants into two separate cohorts of eight fellows, one in the fall and one in the spring. Additionally, each faculty member will work with faculty mentors who were successful fellows during the first two years of the ALF. The results of year two influenced our selection process for fellows in the future, helping us better determine who is most likely to succeed in the program. For example, it is a requirement in 2016 that the faculty have taught their course at least once in the past.

With the help of student and faculty feedback from the first two years, the four current ALCs will be adjusted to include the features that participants have found most valuable. Furthermore, there is also a plan to continue to upgrade and develop new rooms for the upcoming academic year. Note that although the experiences from year two of the ALF have made us even more mindful of how difficult it is to achieve success in large classrooms, we have not given up on this idea. Rather, fellows who will teach large classes in future cohorts will have a lot of experience — both with their course topic and with active learning techniques. Each year, as new faculty members continue to be selected to participate in the ALF, the number of instructors open to and experienced with active learning will continue to grow, necessitating upgrades in classrooms to accommodate active learning. After two years, the ALF is already proving to be an effective means of transforming the future of education at Case Western.

Reflections on Design, Methodology, and Effectiveness

We find the data collected over the first two years of the ALF exciting — and hopeful — regarding the use of active learning and collaborative technology. Students and faculty tended to report greater levels of enjoyment, excitement, and instructional quality (compared to traditional courses) throughout both years of the ALF, via surveys and student focus groups. For both years, classes that took place in an ALC received better reviews, not just based on ratings of technology but across the majority of measures. These early results help confirm the expected benefits of incorporating active learning methods in the classroom.

However, the interesting aspects of year two of the ALF involve the struggles rather than the successes. Entering the third year of the ALF program this fall, we have placed a greater emphasis on faculty selection. For example, we decided to more strongly consider overall teaching experience as well as experience teaching the specific course that the instructor intends to adapt for the fellowship. We believe this will help us develop an even stronger base of CWRU faculty committed to active learning.

Supporting Materials

View the survey instrument online.

Note

- Case Western Reserve University is a private research university in Cleveland, Ohio, with a student enrollment nearing 11,000.

James Juergensen is an assistant professor of Psychology at Youngstown State University. Prior to this he was a postdoctoral scholar at Case Western Reserve University, where he earned his PhD in experimental psychology. He teaches courses in cognition/cognition laboratory, physiological psychology, motivation, and general psychology. His research focuses on automatic approach/withdrawal motivation, breadth of attention, emotion regulation, and health behaviors. More specifically, he is interested in determining how desire for unhealthy foods alters attention and approach behavior.

Tina Oestreich is senior director of Teaching and Learning Technologies at Case Western Reserve University. She works with faculty and senior administrative leaders to support the university's goals in maintaining excellence and innovation in teaching, learning, and research in the realm of academic technology and pedagogy. Oestreich works closely with early adopters to push the edge of the possible, while providing education and training to help the curious, but reticent, members of the academic community who are less familiar with using technology in their work. Her academic background is in teaching language and culture, as well as instructional technology and design. An experienced instructor of German, she is particularly passionate about international collaboration and interdisciplinary learning.

Brian Yuhnke is an instructional designer at Case Western Reserve University and an instructor for the School of Education and Higher Development at the University of Colorado Denver. He adamantly believes that if teaching is boring for faculty, then it is even more so for students. Yuhnke is motivated to engage faculty in the use of technology to make learning fun and innovative. Prior to moving to Cleveland, he did video, supported web conferencing and online lecture recording, researched emerging technologies, and carried out all kinds of other randomness for CU Online at the University of Colorado Denver. He earned a MEd in Instructional Technology and a bachelor of arts in Video and Audio Production from Kent State University.

Mike Kenney is co-lead for Academic Technology and Faculty Support within Information Technology Services at Case Western Reserve University. He loves to try new technologies in the classroom and look for ways to accomplish specific objectives using (and not using) technology. He is a former professor in the Chemistry Department at CWRU, where he taught classes numbering greater than 300 students. He has been recognized for his classroom instruction and his active involvement with student organizations.

© 2016 James Juergensen, Tina Oestreich, Brian T. Yuhnke, and Michael Kenney. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.