Key Takeaways

- Although related research is in its infancy, active learning approaches have increased in popularity as universities seek to help their students more fully engage in the learning process.

- Case Western Reserve University launched an active learning initiative to help faculty use active learning approaches in classrooms optimized for collaborative learning.

- The 12 faculty fellows each redesigned a course that took advantage of active learning methods and technologies, including movable computer displays, flexible furniture, and shared writing surfaces.

- Student surveys and focus groups indicate that both teachers and learners benefit from and appreciate the active learning experience.

At Case Western Reserve University: James Juergensen, Postdoctoral Scholar; Tina Oestreich, Faculty Support & Academic Technology Leader; Brian Yuhnke, Instructional Designer; Mike Kenney, Faculty Support & Academic Technology Leader; Katie Skapin, Instructional Technologist; and Wendy Shapiro, Senior Academic Technology Officer.

As the educational landscape continues to evolve, many universities have incorporated active learning into the curriculum to engender excitement for learning and help students better engage in the learning process. In recent years, some schools have developed classrooms specifically designed to support and promote active learning; although research exists in this area, much remains to be learned.

In 2013, Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) developed an active learning initiative designed to help faculty use active learning instructional methods in two new learning spaces that were optimized for collaborative classroom learning with large movable computer displays, flexible furniture, shared writing surfaces. and so on. Through a yearlong Active Learning Fellowship (ALF), a group of 12 faculty members restructured one class each to include active learning techniques and thereby increase student engagement and success in the classroom.

Project Overview

In preparation for the 2013–2014 academic year, CWRU's Division of Information Technology Services (ITS) designed two new active learning classrooms (ALCs) that were optimized for collaboration both within the classroom and through telecommunication with others off campus. Both rooms used technologies not commonly found in CWRU classrooms, including large displays that let students collaborate on projects and flexible furniture that can be easily reconfigured to suit various learning activities. The classes also feature bright colors and shared writing surfaces, including multiple white boards and writable walls (see figure 1).

Figure 1. An active learning classroom at Case Western Reserve University

To optimize the use of these new classrooms to promote active learning, ITS helped develop a year-long fellowship program to give faculty the resources and support needed to create active learning courses. Twelve faculty members were chosen from across the campus, representing many disciplines and both undergraduate and graduate courses. Through a competitive application process, the faculty fellows were chosen to redesign one of their classes using active learning techniques such as project- and problem-based instruction, collaboration, and formative assessment. Fellows worked with ITS faculty support staff for three weeks in the summer to redesign their courses. When possible, they taught the new course in one of the two ALCs. Fellows who, for time or space reasons, could not teach in the spaces used active learning techniques as much as possible in their traditional spaces.

For the ALF's first year — which was also the first year with the new ALCs — the project's primary focus was to evaluate how students perceived the differences in the newly designed courses with respect to the

- types of instructional methods used,

- amount of active engagement throughout the course, and

- type of classroom (traditional or ALC).

Data Collection Methods

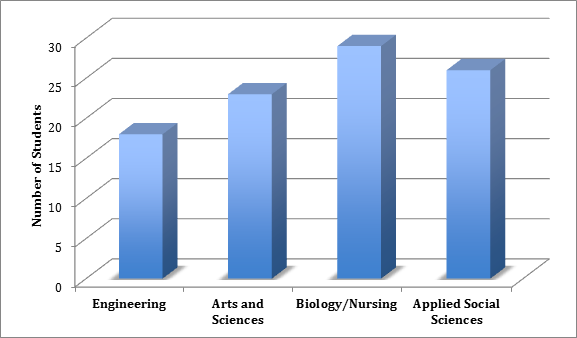

We collected data through a student survey and student focus groups at the end of the semester. We invited students from all 12 ALF courses to take part in a survey, which we administered online using Qualtrics. As figure 2 shows, in total, we gathered responses from 96 students (70 undergraduate in various disciplines and 26 graduate students in the applied social sciences).

Figure 2. Breakdown of student responses by discipline

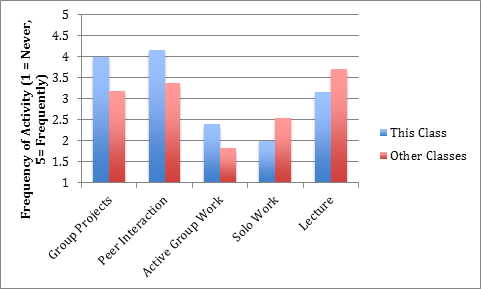

The student survey included one group of questions designed to gather student perceptions about the instructional methods used throughout the active learning course. Specifically, we asked students to compare the frequency of different activity types in the current active learning course to their other (more traditional) courses.

Another section of the questionnaire asked students to respond to a series of questions about the types of technology included in the ALCs. This section was intended to help researchers identify which aspects of the new classrooms students found especially valuable; their choices included the rolling pod chairs, rolling tables, writable walls, large rolling display computers, and/or the lighting.

A final set of survey questions asked students how much active engagement the ALC instructional methods stimulated, as well as how active engagement affected their learning and enthusiasm in the course. Finally, we asked students if they would recommend that the course be taught in the same way in the future.

For the student focus groups, we enlisted 16 student volunteers to discuss various topics, including how the ALF affected student experiences in the restructured courses and how the learning spaces and technologies affected the curricula and student learning. We also asked students to discuss how technology was used in the classrooms.

Data Analysis Methods

We analyzed the survey data using SPSS and Qualtrics software. We gathered descriptive statistics to examine the central tendency and variability for the targeted dependent variables and conducted difference-of-means tests to investigate potential differences between subgroups within the study (such as male versus female, classroom type, and so on). We used NVivo software to organize the focus group data and classify it into nodes based on various themes (such as use of technology and engagement with material).

Findings

Students were generally positive in their responses to both the active learning instructional methods and the various technologies used in ALF courses.

Active Learning Strategies

As part of the survey, we asked ALF students to compare how frequently various instructional techniques were used compared to what was typical in their other classes. Students reported significantly higher frequencies of in-class active group work, group projects, and interactions with peers regarding course-related content in ALF classes. Conversely, these students reported that their traditional classes included more incidences of lecture and solo work. These results indicate that the ALF instructors successfully designed their courses to involve more active, hands-on techniques (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Classroom activities compared to traditional classes

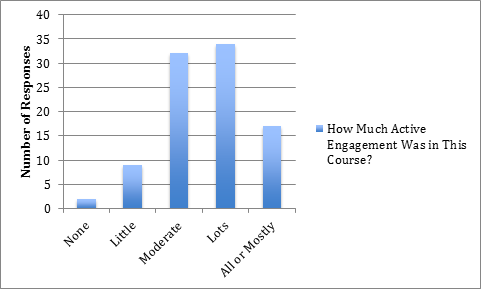

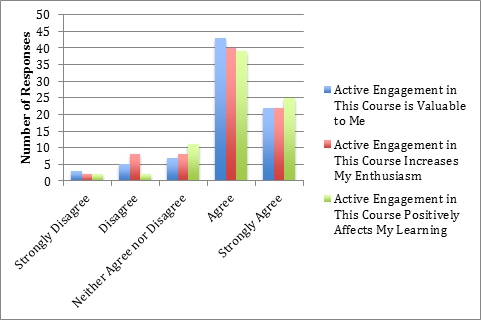

By including additional active learning techniques in the classroom, the expectation was that students would be more actively engaged with the material, the instructor, and their peers. In the survey's second part, students indicated relatively high active engagement in the ALF courses. Furthermore, as figures 4 and 5 show, these students appreciated this active engagement, reporting that active learning in these courses

- was valuable to them,

- increased their enthusiasm for the course, and

- positively affected their learning.

An especially interesting finding was that the majority of students (73.33 percent) said they would prefer the surveyed course be taught in the same way in the future.

Figure 4. Reported active learning

Figure 5. Impact of active learning in the classroom

Analyzing the focus group data yielded themes that were consistent with the student survey data. First, students reliably reported higher levels of active learning and engagement with the material in classes taught by an ALF faculty member. Among the student comments were the following:

"I was never bored in class. I was always actively, completely engaged in what I was doing. Whenever one of us got stuck, we bounced ideas off of each other."

"I am so engaged that I didn't clock watch at all. Is there a clock in here? I didn't even notice that."

"Doing a class like this in just one format may get boring. Having so many different methodologies using these different technologies made it more interesting and informative. I need more going on than just PowerPoint. Using these different ways to learn is much more engaging."

"This structure fits my generation much better. It's more engaging, while also allowing for traditional teaching methods. This helps me learn better — it's more hands on. More practical instruction — not just taught something but modeled it, too."

Active Learning Classrooms

A separate section of the student survey included questions pertaining to the two new ALCs used for some of the fellowship program classes. Students in those classes identified the rolling "pod" chairs, large rolling display monitors, and movable desks as especially valuable in relation to the active learning techniques used during class. Furthermore, students enrolled in fellowship courses taught in ALCs reported significantly higher levels of active engagement compared to students in fellowship courses taught in traditional classrooms. This could indicate that instructors with more technological resources were better able to incorporate active learning techniques into their courses. Again, the student focus group data supported these survey findings:

"I definitely felt more engaged in this class. I was more alert. I was awake."

"What I liked about the classroom was that it was comfortable and interactive, and it didn't feel daunting in the way that it could have been."

"The chairs were comfortable. I always have a ton of stuff. Having comfortable chairs and sufficient space was nice."

Communicating the Results

We communicated the study's results to the faculty and administrators who were interested in improving the quality of teaching among CWRU faculty. We gave presentations at senior staff meetings and wrote summaries that we provided to the stakeholders.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Early findings indicated that the ALF succeeded in helping faculty members achieve their instructional goals. As a result, CWRU is continuing — and improving — the ALF for the upcoming academic year. Twelve new faculty members have designed courses based on active learning strategies. Also, given that both students and faculty prefer courses conducted in the new ALCs, two additional classrooms have been designed and implemented for the new fellowship year. As the ALF continues, CWRU's active-learning-based courses should increase commensurately.

Given that it was just the ALF's first year and our first semester using the new ALCs, we were thrilled with the data we collected and found the results to be quite promising. Most students and faculty members indicated an excitement and appreciation for active learning and considered it to be a valuable learning and teaching method; this appreciation was enhanced when courses were held in the ALCs. These early results have helped confirm the expected benefits of incorporating active learning methods in the classroom.

Despite these positive results, we observed some weaknesses in our data collection that we plan to address in the ALF's second year. First, we plan to collect additional information in the student survey. To better gauge the active learning methods' impact in the classroom, we plan to ask questions related to the SAMR (Substitution Augmentation Modification Redefinition) model, teacher–student psychological relationships, the effectiveness of the instructor's use of the classroom, and how well the course content and classroom fit together. Moreover, to increase student response rate, student surveys will be administered in class rather than online. Finally, to explore the relationship between personality variables — including extraversion, social interaction anxiety, and learning preferences — and enjoyment and success levels in active learning environments, we plan to administer additional questionnaires. Collecting this additional data should provide even greater insight into how we might be able to continue advancing in this exciting field of academic instruction.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Matthew Barritt for helping us with the development and administration of many of the assessment methods employed in this project. His assistance was instrumental to the success of our program assessment.

© 2015 James Juergensen, Tina Oestreich, Brian Yuhnke, Mike Kenney, Katie Skapin, and Wendy Shapiro. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 license.