![E-Content [All Things Digital] E-Content [All Things Digital]](http://www.educause.edu/apps/er/images/e-content2010.jpg)

Rebecca Kennison and Lisa Norberg are the two principals at K|N Consultants, a not-for-profit specializing in open-access strategies, change management and leadership, and continuing education and curriculum development.

The open-access movement, fueled by the digital revolution, is transforming the business of scholarly communication, affecting the entire value chain. Rapidly emerging technologies have been crucial enablers of this transformation, blurring traditional roles and attracting new participants. The infrastructure and the economic framework established to support a centuries-old model of scholarly publishing are no longer adequate to the task. We believe that a radically different approach is required—one that is open, flexible, collaborative, and networked.

What does that mean? If we look at how digital publishing generally and open-access publishing specifically have evolved, what we see is a project-based approach. From PLOS to Collabra, from Knowledge Unlatched and PeerJ to the Open Library of Humanities, from ArXiv and SCOAP3 to LOCKSS and the Digital Preservation Network—and others too numerous to mention—each represents a separate project or platform, with each taking a different but similar approach to dealing with an increasingly dynamic landscape. Each project has a purpose and a specific issue it intends to address, with stated goals and explicit deliverables. Each project also has a unique funding model, although quite often many of them are similar. Still, how often can all of these projects draw from the same wells (usually funders for startup money and libraries for ongoing support), especially since there are new projects and players all the time?

We are not the first to recognize the precarious nature of the current situation. Alma Swan and Caroline Sutton point out: "Many significant [infrastructure] services still depend on such 'soft' funding sources."1 In response, the team established the Infrastructure Services for Open Access (IS4OA) to "facilitate easy access to Open Access resources by providing a free-to-use discovery service for all users and a means to enable libraries to integrate Open Access publications in their services (library catalogues, web-portals etc.)" Similarly, in 2012 the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) and Vanderbilt University created the Committee on Coherence at Scale for Higher Education to "examine emerging national-scale digital projects and their potential to help transform higher education in terms of scholarly productivity, teaching, cost-efficiency, and sustainability." Both of these initiatives recognize and highlight the need to establish a more comprehensive infrastructure across higher education.

Overlaying the current open-access environment is another layer of complexity. At the same time that we are trying to build the necessary infrastructure, the elements that compose scholarly communication are changing. For hundreds of years, books and journals have been the defining products of both the mode of communication and what counted as the record of research and scholarship that needed to be collected and preserved. In a recent OCLC Research report, the authors discuss how new technologies are influencing the nature of scholarly communication and what constitutes the scholarly record. It is now possible, and increasingly required, to include the evidence or "raw materials" of research, such as data sets and computer models, alongside the more traditional outputs—all of which could become part of the scholarly record.2 And increasingly, research and learning objects developed from that research are presented in formats uniquely created for use in an online environment, from interactive textbooks to multimodal web projects.

Stakeholders in the scholarly communication ecosystem have struggled to connect these projects to some kind of coherent and functioning whole. To build a scalable and sustainable scholarly communication infrastructure, we need to take a more holistic view of the entire system. The infrastructure has to accommodate new workflows—from discovery to preservation—and it must be built on a solid funding model.

But what do we mean when we talk about infrastructure in the context of scholarly communication? Certainly many elements of the current system are likely to continue into the foreseeable future, and the infrastructure will need to support those elements and related activities, in addition to the new and evolving modes of communication. Researchers will continue to share their findings through the written word, and peer review of some kind will continue to be an important part of the process. That work will still need to be disseminated and made discoverable. It will also still need to be preserved so that future generations of students, teachers, scholars, and researchers can have ongoing access to the scholarly record. Standards and best practices will continue to be developed and adopted to guide this work.

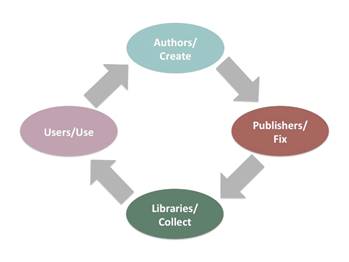

Figure 1. The Traditional Scholarly Communication Lifecycle

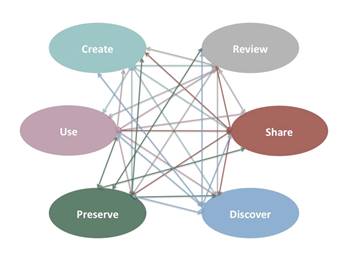

Yet the changing nature of the scholarly communication system requires an infrastructure that is open and flexible, with the capacity to accommodate different forms of communication, a scholarly record that is no longer fixed, and an expanding base of users and stakeholders. Rather than the traditional scholarly communication lifecycle (see Figure 1), scholarly communication today is a networked system in which anyone with the technological expertise and proper connectivity can create, review, share, discover, preserve, and use the output of global research at any point in the process (see Figure 2). As Mark Edington recently articulated: "The central point … is that the whole structure we have inherited as 'the way things are done' is no more and no less the consequence of an answer given under a set of prevailing circumstances to a question of basic utility; it is not the creed of a transcendent reality."3 It is time for us to recognize that a new set of circumstances requires new answers, a new approach.

Figure 2. Scholarly Communication as a Networked System

In this highly networked world, collaboration and resource sharing are not simply collegial; they are essential. The infrastructure to support and maintain this world needs to be vastly different from the one built to support a much more straightforward communication system. No longer can projects (whether books or journals or individual standalone platforms) be funded in the short term by soft money from grants or by subventions from institutions to establish a fixed product that can then be sold to individual libraries; the traditional cost-per-item or lump-sum-per-bundle pricing model is rapidly becoming obsolete. Recent hybrid solutions that charge authors or their funders, in addition to their institutions' libraries, are not sustainable. Research output that is not fixed or static must be supported; the same is true for new forms of teaching and learning materials. The new network of knowledge creation can be used in and by any sector of the educational system. Because the communication requirements are not only more complicated but also more equitably distributed, libraries alone can no longer support this infrastructure. As we have pointed out in our white paper on the topic, the cost to support and sustain this infrastructure must come from everyone who benefits from it.4 It is time not only to discuss what such support looks like—including which organizational practices, technologies, and social norms need to established or modified—but also to focus serious effort and to commit substantive resources toward building the infrastructure that will provide for a robust and open, flexible and constantly evolving, shared and sustainable research and education ecosystem.

- Alma Swan and Caroline Sutton, "Sustainability of an OA Infrastructure," Information Standards Quarterly 26, no. 1 (Summer 2014), 13.

- Brian Lavoie et al., The Evolving Scholarly Record (Dublin, OH: OCLC Research, 2014).

- Mark D. W. Edington, "The Commons of Scholarly Communication: Beyond the Firm," EDUCAUSE Review 50, no. 1 (January/February 2015).

- Rebecca Kennison and Lisa Norberg, A Scalable and Sustainable Approach to Open Access Publishing and Archiving for Humanities and Social Sciences (New York: K|N Consultants, April 11, 2014).

© 2015 Rebecca Kennison and Lisa Norberg. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 50, no. 3 (May/June 2015)