Lisa Ho, Campus Privacy Officer, University of California, Berkeley

It's common to see privacy pitted against security in the form of the question, "How much privacy are we willing to give up for security?" Some call the security vs. privacy debate a false choice and suggest the debate is actually liberty vs. security, or liberty vs. control, or privacy vs. cooperation. At the University of California, Berkeley, we are replacing this longstanding polemic with a triptych of interrelated and overlapping terms: autonomy privacy, information privacy, and information security.

Using this new terminology, we are in the midst of reopening well-trodden deliberations about what monitoring controls should be allowed on the campus network. As we assess new technology options using this new language, we are also embarking on a new information risk-governance process. We aim to carry these discussions from senior technologists in the server room to campus leadership to engage in the difficult decisions around balancing the multiple and sometimes competing values and obligations of accountability, academic freedom, and transparency.

Terminology

The 2013 report of the University of California Privacy and Information Security Initiative (dubbed the PISI "pee-zee" Report) defined two types of privacy:

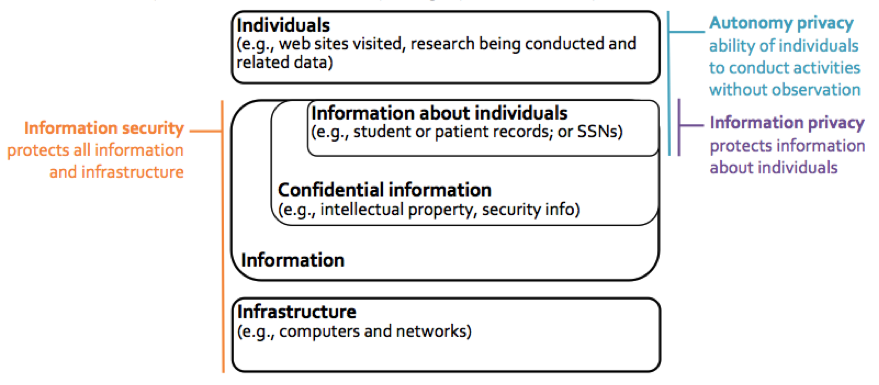

- Autonomy privacy: an individual's ability to conduct activities without concern of or actual observation, and

- Information privacy: the appropriate protection, use, and dissemination of information about individuals.

- Additionally, information security was defined as the protection of information resources from unauthorized access, which could compromise their confidentiality, integrity, and availability.

Information Privacy and Autonomy Privacy Conflicts

In the triptych model, it's not a zero-sum game between security and privacy. Information security supports, and is essential to, autonomy and information privacy. Yet, regardless of different terms, the old conundrum remains that common best practices for protecting the information privacy of the students, employees, and other individuals who have entrusted personal information to the university can negatively impact the autonomy privacy of the users of university networks and systems (sometimes the very same individuals whose information privacy we are trying to protect).

For example, analyzing the location of users logging into campus systems might be considered an industry standard best practice for identifying potentially compromised accounts. Logins from multiple countries simultaneously or within a short time span can indicate compromised credentials. Most users notified of the possible compromise are thankful for the warning; others respond that they are traveling or provide some other explanation. The reason is not deemed pertinent to information security operations, just whether or not it is expected. Additionally, if the location information is stored, it can be useful in determining attack patterns.

On the other hand, on a campus whose members regularly challenge institutions of power, politics, and social norms, storing such location-tracking information can be viewed as a "chilling" invasion of autonomy privacy.

Autonomy privacy is an underpinning of academic freedom and is related to concepts such as the First Amendment's freedom of association, anonymity, and the monitoring of behavior; for example, by identifying with whom an individual corresponds or by building a profile of an individual through data mining.

Academic and intellectual freedoms are values of the academy that help further the mission of the University. These freedoms are most vibrant where individuals have autonomy: where their inquiry is free because it is given adequate space for experimentation and their ability to speak and participate in discourse within the academy is possible without intimidation. Privacy is a condition that makes living out these values possible.

—PISI Report

Although the UC Statement of Privacy Values and Privacy Principles introduced in the PISI Report is a recent addition to UC's canon of ethics, the longstanding priorities from which they emanated are the basis of policy dating back to the year 2000. The UC Electronic Communications Policy (ECP) protects the privacy of electronic communications, including metadata and transactional data, from examination or disclosure without the holder's consent (with limited exceptions). Because autonomy privacy protections are prone to slow and quiet erosion when weighed against immediate and monetarily costly information privacy risks, this policy provides a thumb on the scale of autonomy privacy.

Yet, even if the ECP successfully controls access to this information to prevent abuse by campus entities, if we collect it, we do not have similar ability to guard against subpoenas or other requests by law enforcement or federal agencies, such as National Security Letters or subpoenas with gag orders. And there is little assurance that it would not be used to monitor the travel of a student from Iran, undocumented students participating in California DREAM Act programs, or Civil Rights activists agitating for African-Americans' right to vote.

What about the argument that the government has other ways to collect this information, so we are only handcuffing ourselves by not fully using the information? Until the social debate has concluded that such government surveillance is justified, collection by the university would seem to create a spiraling deterioration of protections. (If the university has travel information to detect compromised credentials, why shouldn't the government have it, for example, to prevent domestic terrorism? If the government has it anyway, why shouldn't the university keep it to protect security and infrastructure?)

Governance

Decisions about balancing the legal and moral obligations for data stewardship and information privacy against the mission-critical values of academic freedom and autonomy privacy ultimately need to be made by a broadly representative group of campus leaders entrusted to weigh the multiple costs, risks, and benefits to the institution and society and set the university's vision. To this end, Berkeley's newly minted Information Risk Governance Committee is poised to take on review of a slate of information collection proposals in the coming months.

My optimism (and trepidation) as we strive to define principles and structures for solving these dilemmas is reflected in the PISI Report’s assertion: "How privacy is balanced against the many rights, values, and desires of our society is among the most challenging issues of our time."

© 2015 Lisa Ho