To be successful, the chief privacy officer needs to collaborate with many other administrative and academic offices to converge on an institutional approach to privacy in higher education.

This article is excerpted from Higher Education Chief Privacy Officers Community, The Higher Education CPO Primer: A Welcome and How-To Kit for Chief Privacy Officers in Higher Education (EDUCAUSE: June 2023). The 2023 CPO Primer merges two earlier publications from the Higher Education Information Security Council (HEISC): a 2016 "welcome kit," which provided an overview of the function of the chief privacy officer (CPO) in higher education and set out baseline knowledge for those who are or aspire to be CPOs, and a 2017 "roadmap" for how to kick-start or enhance a privacy program and how to operationalize it using the frameworks, key components, and resources in the welcome kit. The 2023 CPO Primer also updates aspects that have changed, including considerations arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Americans are concerned and confused and feel a lack of control over their personal information. A 2019 Pew Research Report finding points to the fact that people do indeed care about their privacy.Footnote1 So do students. There is a general belief that people who have grown up using digital technologies—those born in 1983 and later—have little concern for the privacy of their data.Footnote2 As instructors conduct courses online and as analytics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning are used to optimize outcomes for students, privacy becomes increasingly important. As one student put it in a 2021 research study:

I'll say that I'm not as worried about my university taking my data. But I will say after watching The Social Dilemma on Netflix, I think that data usage is completely on my mind…. I still wouldn't say it's crippling. I don't, like, stay up every night thinking about it. But it's definitely more of [an] awakening of how much information is stored and how much is used on a daily basis.Footnote3

This issue was further brought to light during the COVID-19 pandemic as colleges and universities struggled to balance public safety and privacy.Footnote4

As campuses attract diverse groups of students, faculty, and staff from around the world and establish global programs, they must comply with a plethora of privacy laws and regulations. Laws, such as the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), recognize privacy as a fundamental human right and set forth many privacy-protection requirements, including specific data-subject rights.

Heightened data privacy expectations and the proliferation of privacy laws are not the only drivers behind higher education's growing focus on privacy. Mission-driven higher education institutions uphold values such as integrity, respect, accountability, and autonomy that are tightly woven into their identities and reputations. They compel institutions to go beyond legal compliance and actively support and promote ethical and equitable practices. These core values closely align with principles for protecting privacy. CPOs must view the development of privacy programs not only as a means for compliance but also as a mechanism for equity and ethics.

Privacy plays a particularly important and complicated role in higher education because of the teaching, learning, and, where applicable, research, patient care, and public service missions of colleges and universities. Moreover, privacy is a complex, evolving, and often personal construct that holds major implications for individuals, institutions, and society at large.

Colleges and universities have multiple privacy obligations: they must promote an ethical and respectful community and workplace, where academic and intellectual freedom thrive; they must balance security needs with civil and individual liberties (see table 1), research and institutional improvement opportunities afforded by big data analytics, and new technologies with significant privacy implications, all of which directly affect individuals. Institutions must be good stewards of the troves of personal information they hold, some of it highly sensitive. Finally, they also must comply with numerous and sometime overlapping or inconsistent privacy laws.

|

Civil Liberties |

Freedom of thought, speech, and expression Freedom of social and political activities Freedom of association Limits on authority |

|---|---|

|

Individual Liberties |

Promotion of individuality Ability to grow and change Autonomy and control over self Ability to control how much is revealed about one's self |

As individuals—whether as students, faculty, and staff, or as part of an institution's extended community of alumni, donors, parents, patients, volunteers, athletics fans and event attendees, and many others—we expect colleges and universities to properly safeguard the data they hold about us. But as students, faculty, and staff we are also concerned with having an environment that nurtures student growth and development, free inquiry, independent research, and academic freedom to develop new knowledge. Privacy is an important condition for meeting these expectations, and institutions of higher education therefore play a critical role in the social discourse on privacy.

Words of Wisdom from Higher Education CPOs

- "Privacy is a process not a solution. Work on embedding it in operations, program management, application development, etc."

- "When evaluating and implementing new technologies or security safeguards, keep in mind privacy by design, simplified user choice, and transparency.Footnote5"

- "Privacy values change with cultures and generations—continually evolve your program."

- "Position privacy as an enabler rather than a hurdle; be a collaborator rather than a naysayer."

- "Understanding the goals and needs of your stakeholders is crucial in order to most effectively implement good privacy practices."

The Privacy Officer and Privacy Function

Compliance has been the traditional realm of the privacy officer. Compliance with applicable contractual terms, as well as with state, federal, and international regulations, however, is insufficient to meet the expectations and needs of the higher education community. The higher education environment affords the opportunity and challenge to work on privacy matters that are often more abstract and complex and beg for a shift in culture with regard to information governance. Because the very mission of colleges and universities includes the cultural and philosophical issues that surround academic freedom, student growth and development, and research and discovery, there are many complex layers for higher education privacy officer engagement.

"Where does privacy live?" is a perennial question, particularly for institutions that are newly forming this function. Privacy overlays an institution's operations and organizational chart, with each institution anchoring the privacy function differently, depending on the culture and structure of the campus. Typically, privacy is housed within compliance, general counsel, IT, or an academic administrative office. Regardless of organizational structure and reporting lines, the chief privacy officer needs to collaborate with many other administrative and academic offices to converge on an institutional approach to privacy. They need to closely consider that approach, in order to avoid too narrow of a focus driven solely by their place in the organization or by regulatory activities alone.

In that regard, it is important to recognize that privacy is distinct from information security. Security is fundamental in ensuring privacy and must be tightly aligned, but security in itself is insufficient. Data can be secured from external threats but still at risk to be used in ways that violate a data subject's privacy, such as when data is used in ways other than the purposes for which it was collected from the data subjects or without their consent. Privacy layers ethics of data use and rights in data on top of the controls afforded by a strong information security program.

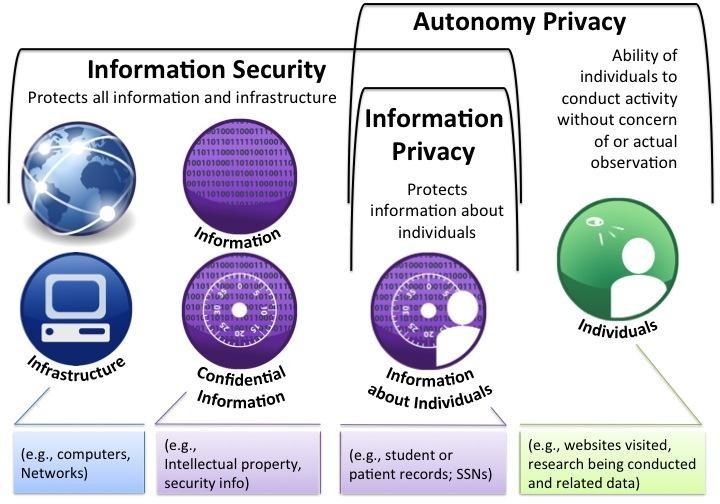

Understanding how privacy and information security fit together, and how their domains and goals diverge, is critical when establishing a privacy program. Generally, a privacy program focuses on the laws, practices, and norms around how information is collected, used, and disclosed; on data-subject rights regarding their data; and on norms around surveillance and observation (see autonomy privacy in figure 1). An information security program focuses on protecting institutional data and the IT services that support it from cyberattacks and other types of unauthorized disclosure or access. Figure 1 outlines the synergies and distinctions of the privacy and security domains in higher education.

The information security function is critical for information privacy—for protecting personal information (as well as nonpersonal information and infrastructure) from unauthorized access. Yet frequently, controls that strengthen information privacy (such as monitoring system access logs) can weaken autonomy privacy. Balancing autonomy privacy interests with information privacy interests, as well as other values and obligations (such as data-subject rights in their data, transparency, accountability, functionality, and efficiency), is a unique determination for each institution. Representing privacy in these conversations is a key responsibility of the CPO and argues for maintaining this role as distinct from, but closely partnered with, the chief information security officer, as institutional circumstance allows.

Within the boundaries set by the law and applicable regulations or contractual requirements, an institution has discretion to develop its approach to privacy. Some of the factors may include:

- Sustaining an environment where faculty and students are free to inquire, experiment, discover, speak, and participate in discourse without intimidation

- Protecting against and responding to modern-day cybersecurity threats

- Protecting the interests of individuals and assuring they have appropriate influence over data about themselves

- Pursuing opportunities for use of data in medical treatment, research, and student success

- Facilitating shared governance of information

The CPO plays a key role—if not a leadership role—in defining this institutional balance, often facilitating the conversations around privacy's import for individuals, the institution, and, by extension, society.

Notes

- Brooke Auxier, Lee Rainie, Monica Anderson, Andrew Perrin, Madhu Kumar, and Erica Turner, "Americans and Privacy: Concerned, Confused and Feeling Lack of Control Over Their Personal Information," Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, August 17, 2020. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Jasmine Park and Amelia Vance, "Data Privacy in Higher Education: Yes, Students Care," EDUCAUSE, February 11, 2021. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Jasmine Park and Amelia Vance, Higher Education Voices: College Students' Attitudes Toward Data Privacy (Future of Privacy Forum), October 25, 2021. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Adam Stone, "COVID-19 Has Altered Student Expectations for Data Privacy," EdTech, April 28, 2021. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- See "White House: Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights" and "FTC Issues Final Commission Report on Protecting Consumer Privacy," Federal Trade Commission, March 26, 2012. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

Susan Bouregy is Chief Privacy Officer at Yale University.

Jeff Gassaway is Information Security and Privacy Officer at the University of New Mexico.

Blanche Stovall is Privacy Lead at The New School.

Svetla Sytch is Assistant Director of Privacy and IT Policy at the University of Michigan.

© 2023 EDUCAUSE. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.