An online project asks students and instructors to reflect on their thoughts and their interactions with others in order to build community, inclusion, motivation, and empathy.

An Actor's Musing, by Susan Russell

After a twenty-five-year career as an actor and six years as an MA/PhD student, I was hired as a professor in the Penn State School of Theatre in 2006. The environment of twenty-first century higher education was new territory, and because I remained an actor, I fell back on an actor's foundational skill: observation. My first observation was a big one: my students, to greater and lesser degrees, did not understand what thinking is, how to do it, and why they should spend their precious time doing whatever "thinking" might actually be. To them, opinions were knowledge, offense was inquiry, arguments were conversations, and any brain process that might slow down their exhale of information was not worth the air it required to take a full breath. Some of their obstacles were behavioral, but their primary points of opposition could be chalked up to perceptions of time and learning.

I have watched and listened to my students for fourteen years now, and the best image I have for how they feel about time and learning can be understood by watching the iconic episode of the I Love Lucy show when Lucy and Ethel get a job wrapping candy on an assembly line. Lucy and Ethel can't keep up with the speed of the conveyor belt, so they start eating the candy and hiding what they can't eat in their hats. When the boss comes in, Lucy and Ethel can't speak because their mouths are full. Most important to this conversation about time and learning, however, is that Lucy and Ethel are afraid to speak because they think they will get fired if the boss finds out they can't keep up with the conveyor belt. In business, time is the enemy of an assembly line, and in education, time is essential for teaching and learning. I thus began to wonder: in an educational system defined by business practices, how can I teach and how can my students learn?

I took the opportunity of a faculty fellowship at Teaching and Learning with Technology (TLT) to create an online place where students, staff, faculty, administration, and eventually community members can exercise mindful personal and collective inquiry into the thoughts that form cultural connections and inclusions or exclusions. TLT formed a project team of learning designers, multimedia developers, and researchers to support the project. The project team, including myself and the other four authors of this article, developed the Moral Moments Project (MMP), a unique curricular approach to navigating and even altering an entrenched educational paradigm.

A Team's Challenge

We cannot change the past, but we can address the present needs of our young people by reframing teaching and learning in our classrooms and our communities. The Moral Moments Project is just such a reframing. The Moral Moments Project is a movement, a lifestyle, a sustainable process of self-reflection and community building based on knowable, teachable, and repeatable skills of communication, empathy, compassion, and strategic decision-making. Empathy and compassion are the landmarks of mindfulness, and because these elements are required to create a civil society, meeting this challenge became the very beating heart of the MMP.

Everything depends on the delivery, and perhaps the greatest challenge we face as the MMP team is using technology as a springboard for students to define, experience, and practice empathy and compassion. Given the ubiquity of technology, it would seem logical to meet students in a technological space. Yet technology and mindfulness don't automatically make good bedfellows; there must be intentional balance between the two. Meeting the students in their space of technology required us to rethink the what's and how's of a website and a Canvas course shell. The website would have to offer curricular guideposts and be resource-rich. The course would have to be conceptually explainable and functionally nimble.

A Digitized Synergy between Technology and Community

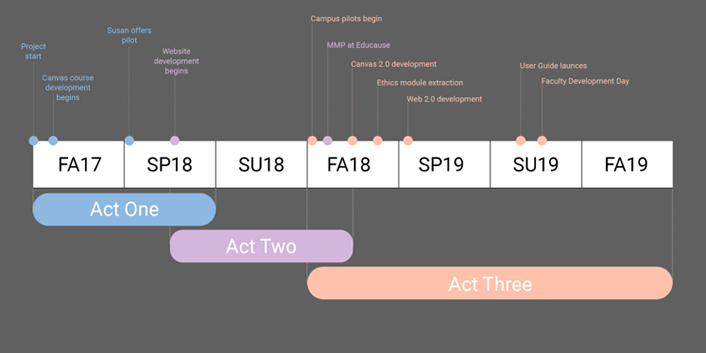

We used a design-based approach to develop Moral Moments. We found ourselves constantly empathizing with the potential users and defining and redefining our challenge. Ideating, prototyping, and testing has tended to follow the academic calendar, from fall 2017 to the present, and in the parlance of theater, the project evolved over three acts (see figure 1).

One goal of designing and developing the course and the website was to maintain an environment of empathy and compassion. The first act was building an initial iteration, a pilot, of the course that was first taught in spring 2018. Built within Penn State's learning management system, Canvas, the MMP pilot consisted of four pillars: morals, ethics, action, and faith. Each pillar was assigned a module. Each module began and ended with a pre- and post-assessment. Between the assessments, students interacted with online resources outside of class and then joined their class community in person to discuss. The online resources comprised a collection of definitions, articles, videos, podcasts, and engagements and encounters.

Students experienced the modules one at a time, following a similar set of experiences and activities within each. Specifically, they read and reflected on multiple definitions of the specific pillar—for example, multiple definitions of "morals." Then they were assigned to watch pillar-related TED Talks and listen to pillar-related podcasts, choosing from among a variety provided. As with definitions, reflection followed watching and listening. Engagements and encounters, where students were instructed to use their skills by interacting with others, followed the reading, watching, and listening. Each module was capped with an opportunity for strategic decision-making around that pillar.

From the pilot, we learned that the activity progression through each module works—the reflection prompts result in meaningful writing from students. There is a lot of writing to read, so instructors need to be prepared for that. We also learned that students had an overall great experience. In a focus group session with the whole class, students wanted to know, "What's next?" They were not ready for the conversation to end.

The second act consisted of the website, which was built on a Penn State–hosted instance of WordPress. Primarily influenced by the Canvas course, the first iteration of the website was skeletal—a handful of pages; a small selection of definitions, articles, podcasts, and videos; and the beginning of a blog. This website also hosted a substantial collection of 88 Penn State student videos that the project team created specifically for the project.

Near the end of the second act, the website began to evolve. We increased the number of definitions, articles, podcasts, and videos for each pillar. The number of pages and project-specific videos significantly increased, including separate student and faculty sections, six faculty development videos, faculty development resources and activity examples, and a mechanism for anyone to request author access to contribute to the blog. The revised web space emerged as a repository of current articles, definitions, podcasts, videos, TED Talks, and engagements and encounters, organized in a digital format to allow instructors to narrow down their selections and choose from among these materials to use in their courses, supplement with their own resources, or ask students to choose their own topics as well.

We realized that we also needed to revise the structure of the Canvas course. The first iteration of the course was built as a holistic and complete Moral Moments course curriculum, with which an instructor could teach an established Moral Moments course from beginning to end. We soon realized, however, that most instructors preferred curriculum materials—a kit of parts—to assemble their own Moral Moments experiences to complement the courses they were already teaching. The Canvas "course" needed a framework that would be flexible enough for instructors to adapt it to their own needs within their courses without losing the integrity and spirit of the overall Moral Moments Project. Act three saw the deconstruction and reconstruction of the course space. We reorganized and chunked content so that it could easily be broken down and applied across multiple instructors' use cases without losing the essence of the project. In addition, we needed to consider practical elements such as maintenance and a format for distributing the content.

Modifications to the LMS course space included:

- Redesign of the modules so they can be used as stand-alone content while keeping the pillars, essential elements, and social agreements visible and within each. Rationale: Instructors were using the Moral Moments Project in many different settings. Stand-alone pieces can easily be plugged into existing courses if instructors are unable to teach all four pillars in one course.

- Explicit direction of the MM audience, instructors or students, to the website whenever possible to access curated resources (podcasts, videos, articles, definitions, etc.). Rationale: This reduces overall maintenance and allows for the changing/updating of content to occur in one location rather than multiple digital spaces.

- Development and inclusion of instructor-only content, such as user guides, sample lesson plans, and scoring rubrics. Rationale: Not all instructors are prepared to teach this type of content. These new materials provide instructors with questioning techniques, examples of what to do when conversations become challenging or contentious, scaffolding they can use for students who may be at different points in their academic careers, and modifications for different course structures.

A Reflective and Responsive Support System

Moral Moments is a time-based, self-reflective, community-engaged process intended to strengthen cultural awareness, emotional intelligence, and critical thinking. In the MMP, students think about morals, ethics, actions, and faith. But before they encounter any Moral Moments content, they are invited to define "thinking" through a specific perspective we call a Moral Moments Experience. A Moral Moments Experience frames thinking as a pause, an intentional time-based process of (1) taking a moment to realize a thought is present, (2) taking another moment to uncover personal perspectives, privileges, and prejudices framing the thought, and (3) taking another moment to use all that self-aware "information" to build a question about the thought. Once the first three steps are accomplished, the thinker (4) brings the "thought question" into a community for discussion and, based on all the information gathered, (5) then makes a personal decision about whom the individual wants to be in the world and how that being might look in words, thoughts, actions, and deeds.

The MMP uses academic articles, TED Talks, podcasts, music, and videos of Penn State students as sources for personal reflection, community conversation, and cultural engagements. Moral Moments Experiences rely on private journal writing, internet sourcing, and community conversations to raise questions about issues such as racial bias, male-patterned violence against women, poverty, community building, and peace. The course is intended to meet the students where they are by helping them identify who they are "being" at any given moment. Written reflections, which are begun in the private space of a personal journal and then brought to a public space of community conversation, are guided by five reflections that flow throughout the course: "I didn't know I…," "I thought I…," "I never thought…," "I was surprised when…," and "I believe…." By their introspective nature, these prompts work to change reactions into responses, opinions into observations, and comments into contributions, and by their practice, students learn to "check in" with themselves when an event, an action, and/or an encounter is challenging.

The course is firmly rooted in a foundational agreement within the community of teachers and learners. This agreement is called The WOMPP Factor and is intended to promote emotional intelligence by identifying obstacles to connecting with someone or something seen as "different." The WOMPP Factor is based on taking personal and collective responsibility for creating an environment for learning, and by attending to these questions:

- Am I willing to learn something new?

- Am I open to a surprise?

- Am I mindful that I am not the only person in the room?

- Am I present so you and everybody around us can be possible?

In this context, the space of teaching and learning opens to the possibility that everyone in the room has something valuable to contribute. This shared experience of worth and value sustains the community of teachers and learners, and shared experiences become the foundation of community building, which is the core principle of a Moral Moments Experience.

MMP instructors are also MM learners in the course. It is both an individual and a shared journey for all involved. Instructors, however, need additional support since they are the MM content integrators and teachers. With the Canvas reconstruction and the bolstered collection of web materials, instructors needed accompanying resources to help them appropriately reassemble the pieces into coherent Moral Moments Experiences for their students. We provided support in three areas:

- Curriculum integration: One incarnation of MM is as a comprehensive Canvas course. We found, however, that instructors were often more interested in integrating carefully selected pieces of content into their preexisting courses. To assist instructors in augmenting their courses, we engaged them in group-level and individual curricular and instructional design discussions. We also developed a user guide, a ready reference available in the faculty section of the website.

- Moral Moments skills: A faculty development day, co-facilitated by MM instructors, gives new instructors opportunities to ask questions and learn from those with MM teaching experience. Over time, and in response to instructor requests, we also created support videos for each of the five Moral Moments elements, lesson plan templates, and a growing blog with crowdsourced implementation and activity ideas.

- Technology troubleshooting: In the early build-out of the MMP, we offered "white glove" technical support for instructors who were not accustomed to using Canvas. As the project has grown, we have directed instructor technical questions to our institution's help desk. The MMP requires a base facility with web and LMS navigation.

A Story of Successes, Challenges, and New Opportunities

We have used both a design-based approach and a program-evaluation lens to improve the MMP design and to understand the efficacy of the project. Since the project's inception, a host of surveys, focus groups, interviews, and instructor meet-ups have given us insight into successes, challenges, and opportunities.

To date, Moral Moments content has been incorporated into a pre-semester orientation, as part of the ethics unit in numerous courses, and as the core content for a large number of first-year seminars across Penn State's multi-campus system. Moral Moments content has been integrated into noncredit, one-credit, and three-credit courses. In fall 2019, the School of Theatre adopted Moral Moments as the anchor of its first-year experience, integrating MM content with programmatic content and requiring all incoming students to participate.

With a few exceptions, use of Moral Moments content is currently optional at Penn State. As such, there is no formal tracking. As Moral Moments has grown and taken root in unanticipated places, we can only estimate how many students and instructors are engaged with MM content. By our records, more than 1,000 students and nearly 40 faculty have engaged with MM content since 2018. While the use of MM content is largely voluntary for faculty, for students required to engage with MM content, there is also room for much personalization and choice.

Feedback and reactions from research participants indicate that the MMP experiences have a positive impact, with 95% of student survey respondents describing their experiences as positive and meaningful and the majority of faculty reporting that they are extremely likely to use the MMP content in the future. In addition, feedback from students and instructors has given us some critical insight into what works and where the project's impact lies.

-

The flexibility of the MMP model and content supports curricular unity while still offering freedom to individual instructors.

"We wanted to bring unity to all of the sections with our HDFS [Human Development and Family Studies] classes; we had been thinking really hard about how to do this, and Moral Moments seemed like a really good way." [Instructor 1, fall 2018]

"I loved it! Since I have been teaching ethics and moral philosophy for years, I was able to infuse other theories and activities into the Moral Moments Project seamlessly." [Instructor 2, fall 2018]

-

Moral Moments helps create a diverse and inclusive community in the classroom by providing students with opportunities to communicate and connect with others. Said one instructor, "[Moral Moments] created a really great atmosphere of inclusion."

"What I witness in the classroom and observe is just [students] communicating with each other and communicating with other students that they normally wouldn't, and asking questions of their peers that they would never have done before." [Instructor 2, fall 2019]

"I will say that [the most helpful outcome of the course] was, for me, interacting with [other] students, too. Because I got to know them, and they got to know me. And, at first, I thought I wasn't going to have any friends and that I was going to be by myself in class. But I got to know them, so every time we did a group worksheet or something, we used to get together, talk about it, and we reflect on it." [Student 1, fall 2018]

"Provides an outlet for students who don't normally speak up in class; space for non-traditionally-rewarded students to speak up." [Instructor 3, fall 2019]

-

Through experiences such as group work, group reflections, and in-class discussions, students have opportunities in a safe environment to communicate and connect, engage in deeper conversations, develop confidence to approach people from different backgrounds and experiences, and build connections and nurture relationships.

"I feel more confident in the way I approach people." [Student 2, fall 2019]

"I'll probably find it very easy to be working with everyone in this room." [Student 3, fall 2019]

"I came from a community where everyone basically agreed with each other…. Nice to come into a community where we can challenge each other." [Student 6, fall 2019]

"I find myself more open. I used to sit in the back and not talk." [Student 7, fall 2019]

-

The interactive and reflective activities provide opportunities for students to practice socioemotional metaemotional skills. These skills include awareness of personal biases and emotions, mindfulness, cultural awareness, curiosity, ability to question, empathy, emotional intelligence, and productive failure.

"Even in as large a class as I'm working with, what we established early on in the classroom in the set of agreements is that we would always be in the act of questioning the question, and the more emotionally charged a situation is, we agreed that that's when the question should be asked. That if you are angry about a topic, if you have heard something that has angered you, we call it 'bring the question to the community.' Literally, the act of bringing a question to community about something that upsets you has created a playing field of communication in a large group of people that is based in peaceful inquiry. And kids are angry. Of course, they preface it, it's so beautiful, they go, 'I am so angry about this, but here's my question for the community.' I love that! It's fine. Whatever you say is fine." [Instructor 2, fall 2019]

-

Content and activities are built to improve students' individual learning and motivational outcomes, such as writing and reflective skills, as well as positive changes in students' willingness to learn and engage.

"I think I've been really surprised by the change in my students. I was surprised by how willing they were to engage.... I was shocked by how many of them dug into this. More than half, most of my class—they were here, they were doing it, they were ready to learn and change." [Instructor 1, fall 2018]

"Two students [for whom] English is their second language, and one of the great unintended outcomes of this course is I watched their writing improve, drastically." [Instructor 2, fall 2018]

The Long-Term Challenges

This course tasks the teacher and the learner in unexpected ways, so it can be a challenge to find people who are willing to, as the team says, "fly in a plane that is being built while you're flying it." The kind of teaching the course asks is the same kind of learning it teaches, which is intuitive, present tense, and rooted in constant checking in with self and community. This approach can take time for everyone in the room, but time spent learning is time well spent. At present, the MMP team is exploring how to scale the course up, which leaves us facing our greatest challenge yet: sustainability. At this juncture, all we can do is what we do, which is keep flying, and time spent flying in this kind of rarefied air is…time well spent.

Susan Russell is Associate Professor of Theatre at the Pennsylvania State University.

Crystal Ramsay is Interim Assistant Director, Teaching and Learning with Technology – Innovation, and Affiliate Assistant Professor, Educational Psychology, at the Pennsylvania State University.

Zach Lonsinger is a Creative Experiences Designer, Teaching and Learning with Technology – Innovation, at the Pennsylvania State University.

Sara Davis is an Instructional Designer, Teaching and Learning with Technology – Innovation, at the Pennsylvania State University.

Tugce Aldemir is a graduate student assistant at Teaching and Learning with Technology – Innovation, at the Pennsylvania State University.

© 2020 Susan Russell, Crystal Ramsay, Zach Lonsinger, Sara Davis, and Tugce Aldemir. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-ND-NC 4.0 International License.