Prior to COVID-19, the faculty at Beijing Jiaotong University (BJTU), Weihai campus, did not teach or offer courses online. But BJTU, Weihai seized the opportunity to refresh its approaches to teaching and learning.

I don't know if American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn would have described the reverberations in higher education due to COVID-19 as what he termed a paradigm shift: a fundamental change in basic practices and concepts. What is certain, however, is that the normal processes of instruction are incompatible with the COVID-19 phenomenon. Perhaps the shift to online education should be considered in the context of Priscilla Wald's outbreak narrative. In its "scientific, journalistic, and fictional incantations," the outbreak narrative "follows a formulaic plot that begins with the identification of an emerging infection, includes discussion of the global networks through which it travels, and chronicles the epidemiological work that ends with its containment." In this formulaic plot is the pattern of reactions that include both scare-mongering and incomparable compassionate responses and engagements. Human existence affirms "the necessity and danger of human contact." The more one distances oneself from fellow human beings, the higher the chances of one's survival.1

This sort of survival requires closures. The formulaic plot of COVID-19 includes, of course, the closing of colleges and universities. At the same time, however, higher education has shown many innovations—across the globe—in its fast and emergent migration into online platforms. Chinese schools went online as well, with the most prominent examples being Duke Kunshan University (a partnership between Duke University in the United States and China's Wuhan University) and New York University Shanghai. Another example is Beijing Jiaotong University (BJTU). In 2015, BJTU opened a campus in Weihai, China. In the same year, the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) became BJTU's first international partner committed to delivering joint degree programs at the new Weihai location. RIT and BJTU offer a joint B.S. degree in Management Information Systems to over 300 students.

For more than five years, the main campus of BJTU has had an online learning platform (see figure 2), which acts as a supplement for classroom teaching, but that platform is not yet available at the Weihai campus. In the past several years, BJTU has also developed over 300 MOOCs, which are more about online resources than courses. Among those MOOCs, 183 are now available for public use through http://www.icourses.cn, an online learning platform supported by the Ministry of Education of China. Of course, most of the online resources are in Chinese and thus are not suitable for the Weihai campus, where several courses are taught in English.

Most of the courses at the Weihai campus are traditional, face-to-face classes, but there are a few exceptions in the BJTU/RIT partnership. One example is "Global Literature," which is a hybrid course: synchronous online lecture, asynchronous online session, and an on-campus two-week seminar. That design is a compromise by BJTU to allow RIT to overcome the challenge of staffing the course. However, students' Confucian aesthetics run contrary to online learning modalities. Chinese students privilege the teacher; they generally remain silent while the teacher speaks. They want to see and listen to the teacher, who transfers wisdom to the students. Online learning challenges and undermines these beliefs and traditions.

The program curriculum is rigorous, and students follow an organized regimen: classes are held from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m., and all students eat at the same time and go to sleep at the same time. The program has been very successful. The office of student services, which is integrated with the academic affairs office, has overwhelming data on the students' enthusiasm about learning and interest in graduate studies. They sharpen that interest through extracurricular activities in leadership and community services. Among the 106 graduates in the 2015 inaugural cohort in the RIT-BJTU program, 83% graduated and enrolled in top graduate schools (ranked according to the QS World University Rankings) in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, China, Singapore, and elsewhere across the globe. The remaining 17% took a year off or joined the workforce.

It would naturally appear that the COVID-19 pandemic would be cataclysmic to the programs at BJTU Weihai. But the resilience of the administrators is notable, especially since the university, prior to COVID-19, did not have the infrastructure for online learning. None of the faculty were trained in online learning because the university did not condone it. Students on the campus cannot access certain websites without the Chinese-approved VPN. UNESCO published some of China's initiatives in response to the crisis, noting that China's Education Ministry worked together with the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology to achieve the following:

- Mobilize all major telecom service providers to boost internet connectivity service for online education, especially for the under-served regions

- Upgrade the bandwidth of major online education service platforms, especially the capacity of the National Cloud-Platform for Educational Resources and Public Service [http://www.eduyun.cn/] in serving millions of visitors simultaneously

- Mobilize society-wide resources for the provision of online courses and resources. More than 24,000 online courses have been made accessible for university students. 22 validated online course platforms, most [of] them empowered by Artificial Intelligence, have been mobilized to provide primary and secondary schools with free online courses.

- Adopt flexible and appropriate methodologies to facilitate learning. Schools and teachers are advised to choose appropriate modes of delivery based on local e-readiness, including online platforms, digitalized TVs or mobile Apps. Teachers have received guidance on teaching methodologies including through live-streaming of online tutorials and MOOCs. The recommended number of online learning hours varies by grade.

- Strengthen online security through collaboration with the telecom sector and online platform service providers

- [Provide] psycho-social support and courses to impart knowledge about the virus and protection against it2

At the BJTU Weihai campus, there is a synergy in the use of educational technology among the students, faculty, and administrators. As noted by Vice President of Academic Affairs Guiping Xiao: "The Academic Affairs Office grasped students' online learning status [in a timely way] through a variety of methods including questionnaires and WeChat groups composed of representatives from different majors to access students' opinions and suggestions on online teaching and learning. Students' online learning experience has been improved and enhanced through continuously finding solutions for newly found problems through negotiation and dialogue."3

Xiao further noted that the migration was based on specific initiatives:

- Support faculty. MOOC resources gathered from well-known overseas websites for online teaching reference have been provided for BJTU teaching staff in Weihai Campus; the teaching requirements and related documents, platform use instructions regarding the rain classroom, the tencent classroom, and related training information are also shared through a WeChat group (see figure 3). The WeChat group contains all BJTU teaching faculty in Weihai Campus and undertakes missions of overcoming difficulties and getting feedback about online teaching.

- Investigate and test platforms. Functions covering a range of live-streaming teaching, online conferences, file-sharing, and group interaction are investigated, tested, and shared in the campus-based Enterprise WeChat platform, which has provided much more diverse choices and backup solutions for online teaching.

- Prepare before the start of courses. One week before the official start of online teaching, the preliminary plan and the platforms adopted for all courses for the first four weeks were well summarized and reviewed. The QR codes of the WeChat interaction group for all courses between faculty and relevant students were collected and shared to guarantee effective exchanges. Students received guidance to test the variety of teaching platforms in order to ensure stable access from across the country to carry out online or offline learning. The IT center established two Enterprise WeChat groups providing instantaneous assistance during the epidemic period to solve technical problems for faculty and students around the clock.

Figure 3. Professors exchanging teaching experiences through the WeChat group - Support online classrooms. An online service working team composed of staff from the Academic Affairs Office, the Student Affairs Office, the Lab Center, and the IT Center was established to solve problems that may arise from the course. Members of the team join prearranged classrooms to collaborate with the professor, providing one-on-one support.

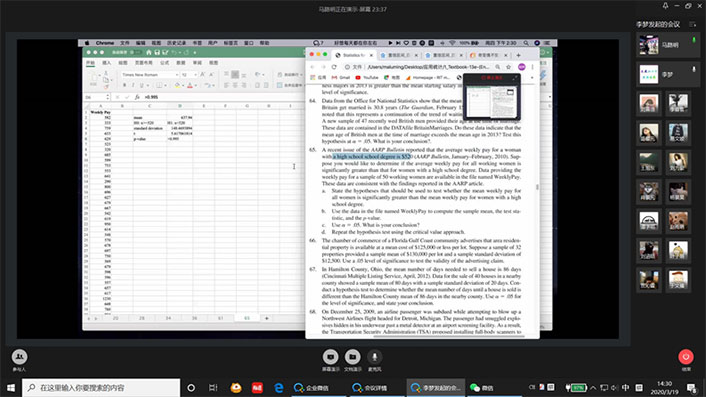

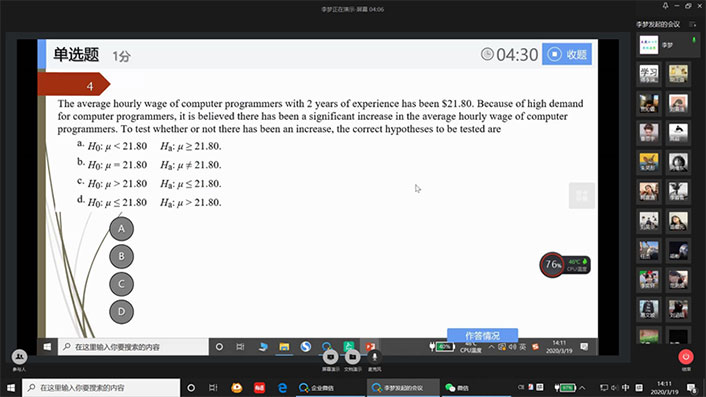

Although students, faculty, and administrators showed diverse perspectives on their transition to online learning, their optimism is inimitable. As noted above, they used Enterprise WeChat, which has abilities similar to those of Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Blackboard Collaborate Ultra. Figures 4–6 are screenshots of synchronous class work in Enterprise WeChat. For the joint degree program in BJTU/RIT partnership, the technology was extended beyond Enterprise WeChat to include a traditional learning management system (myCourses) as well as Zoom and Microsoft Teams. This was done to ensure academic continuity should one technology fail due to security firewalls in China or to the overburdened internet. The institution also extended the delivery method beyond synchronous online instruction to add asynchronous, traditional online activities, hence applying hybrid methodology.

One may argue, then, that BJTU, Weihai is not really using online learning but, rather, remote learning and thus is removed from the burden and challenges of the pedagogical ramifications of online learning. Such a distinction is rather negligible because what they have done is a variety of e-learning and distance learning, which is sustained by the internet; it can be retrieved on-demand through a playback mechanism. As such, their approach produces content that transcends time like any traditional online learning.

To explore further, I wanted to focus on two questions: (1) How has the shift to the online platform affected teaching and learning at BJTU, Weihai? and (2) Can online learning bring about a positive change in the BJTU, Weihai education paradigm? I thus surveyed students and faculty at BJTU, Weihai to determine their understanding and appreciation of online learning.4 Let me share a sample of the faculty's and students' responses. Note that their responses do not discriminate between online learning and remote learning. "Remote" is not in the language of their descriptions. The faculty answered the first question.

How would you describe your experience as a teacher during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with your experience the last semester you were on campus?

- Online teaching seems to suit me better.

- It's a challenge, but I'm getting used to it now.

- I am adapting to online teaching.

- I miss the face to face. However I think the delivery is more organized for students and internet is faster than on campus for most.

- The students are far more engaged.

- It's a little bit strange at first, then everything goes on well.

- They're kind of different and showing me another way to teach.

Students answered the next question.

How would you describe your experience as a student during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with your experience the last semester you were on campus?

- Attention is more focused, but the teacher will spend extra time solving some students' problems because of online teaching.

- Well, I think it's easier to have a lesson on the internet because we don't need to dress up and we can get up later because there's no need to go to a classroom.

- There is less interaction with teachers in online classes.

- Good except for too many assignments and quizzes.

- I think the task of reading is a little heavy. But it is acceptable.

- Amazing, it will be a remarkable experience in my life.

- I think being on campus will be better; we can have more chances to interact with professors to learn more.

- The learning effect is stronger. I can hear what the teacher is saying more clearly and also can record in time. But you can't talk to your classmates as effectively as you do in school.

- In a word, it is great.

- More confused, less communication.

- I think it's completely different. My house doesn't always have a learning atmosphere so that I can be focused on what I am learning. I really worry about my grades.

- The distinction is small.

- Online class is easier.

The students and the faculty do not have unequivocal perspectives on online learning. I asked both groups the following question, and their answers reveal not just a reservation but an apparent disapproval of online learning—while also a recognition of its potential.

What is your perspective on online education?

- It can help us.

- Sometimes it may be useful, but it can't take the place of teaching face-to-face.

- High efficiency.

- I just want to go back to my campus. I don't like online education.

- I think online teaching has less chance to contact teachers than classroom teaching, but I can solve this problem through office hours.

- It is fun.

- I can only say that I prefer the traditional teaching model.

- It has obvious network shortcomings. The bad network influences students' study.

- Hopefully the class will be orderly and we will have a clear understanding of each task and assignment requirements.

- Good and efficient method in emergency time.

- The same as it was before the virus. I have always been a proponent of using hybrid models.

- About the same as before: a good contingency and supplement.

- For some students who really want to study, it is good.

- An excellent way; we have more time to learn by ourselves.

- I still need some time to adapt to it. I think online education needs even more self-discipline than in the classroom.

- It is good.

These responses, overall, underscore some positive dispositions toward online education. There is also a recognition of technology challenges—namely, network connection, novelty of the platform, pedagogy, teacher-student interaction. Those challenges are common in online learning and can easily be overcome. They are not specific to the experience at BJTU, Weihai and are not radically different from what has been described in the abundance of literature on the topic.5 In addition, the Quality Matters (QM) organization has developed rubrics and standards designed to anticipate such issues and offers a system to help colleges and universities provide "well-conceived, well-designed, well-presented" teaching and learning experiences.

The recognition in one of the responses about the need for "even more self-discipline" is relevant. Self-discipline is crucial in online learning; it shows that students are active in the learning process and that they make choices that foster learning. A closer examination of the responses to the questions also shows the adherence by BJTU, Weihai to China's Ministry of Education initiative: "Ensuring learning is undisrupted when classes are disrupted." As the faculty think about teaching well, the students are making sure they are learning; some are worrying about "grades" because they feel they are not learning, but not because of the adoption of online platform. The factor is the students' home environments, which are not often designed for taking online synchronous classes.

The issues notwithstanding, the survey reveals that BJTU, Weihai had a quick recovery from the disruption of teaching and learning by adopting online learning, not minding the hiccups in the beginning of the term. There is, however, a preference for blended learning (hybrid of online and traditional face-to-face learning), and a negligible number of people found the experience of teaching online to be "poor." The factor for that preference is not yet clear to me; yet it would not be unreasonable to speculate that it is based on the need to merge the best approaches between the two media.

The survey results at BJTU, Weihai compare to those reported by Zhang Yu regarding migration to online learning at Tsinghua University, Beijing. Zhang presents a generally positive reception for online learning: "Around 40% to 55% [of] students felt that online and traditional face-to-face teaching are equivalent in terms of general quality. Around 15% to 30% of students reported that synchronous online learning is better than traditional [face-to-face] learning. Around 30% of students thought that traditional [face-to-face] learning outperforms live online learning."6 At BJTU, Weihai 17.5% of the survey respondents were in favor of online learning; 32.5% chose traditional, face-to-face learning, and 50% chose a hybrid of online and traditional face-to-face learning.

Research also appears to privilege hybrid learning. In his book Academia Next, Bryan Alexander states:

The idea of using face-to-face classroom time for what it does best while arranging learning online for what that technology does best seems to have gained a great deal of traction. The terminology may vary (hybrid classroom, flipped classroom) and practices are diverse, from shifting lectures to the asynchronous online world to increasing exercises and student work within the physical classroom, but the general concept appears to be growing. Research suggests that such hybrid or flipped classes produce better learning outcomes than either wholly offline or online classes.7

One thing is very clear: students are still attending classes and pursuing their academic goals despite the COVID-19 pandemic; in addition, there is a recognition of the facility of online learning. Although the survey does not reveal 100% support for online learning, it offers considerable perspectives that adjust the traditional mode of teaching and learning. Given the results, it would be reasonable to recommend that BJTU, Weihai consider online learning in its course offerings and strategic planning as a means to reach a new plateau "through differentiated visioning, rigorous prioritization, purposeful resource allocations and increased morale through confidence in leadership."8 BJTU, Weihai may seek partnerships with other colleges and universities that have established online learning infrastructure and/or have devoted resources to online course development as a way to embark on professional development for online teaching. It may also seek to offer students workshops on how to take courses online. Finally, BJTU Weihai needs to further demonstrate the efficacy of online learning to students' parents.

Sifting through the formulaic outbreak narrative of COVID-19, one can tease out evidence that suggests a paradigm shift. Of course, there will be narratives following the outbreak of COVID-19 as well. Given the web of communal engagements and interactions that emerged in response to the pandemic, one narrative might be described by the words of Cassy Winthrope, a character in Robin Cook's book Invasion: "We're all related. I've never felt like all humans are a big family until now."9 What one sees at BJTU, Weihai with regard to the migration to an online platform may not be radically different from what so many colleges and universities are doing around the world as a result of COVID-19. The migrations could be read as the symbolic shock-absorption that is native to human nature—the need to overcome danger through adaptation. Too, the response bears the traces of Chinese engagement with crisis, wēijī, 危机: a time of danger when one should be careful. It can also be described as a zhuǎnjī (a turn for the better) and as a liángjī or hǎo shíjī (favorable opportunity). COVID-19 inaugurated the moment for BJTU, Weihai to refresh its approaches to teaching and learning and show its ability to come up to date, encounter and sustain change, and absorb the unstoppable innovations that overflow higher education.

Notes

- Priscilla Wald, Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and Outbreak Narratives (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008), p. 2. ↩

- UNESCO, "How Is China Ensuring Learning When Classes Are Disrupted by Coronavirus?" February 19, 2020. ↩

- Guiping Xiao, "Online Teaching Experiences during Coronavirus Outbreak Period in BJTU Weihai Campus" (unpublished manuscript, March 22, 2020). ↩

- The survey, sent to 100 students and faculty on March 9, 2020, was completed by 70 respondents. ↩

- For example, see Mansureh Kebitchi, Angie Lipschuetz, and Lilia Santiague, "Issues and Challenges for Teaching Successful Online Courses in Higher Education: A Literature Review," Journal of Educational Technology System 46, no. 1 (2017), and Melissa J. Kenzig, "Lost in Translation," Health Promotion Practice 16, no. 5 (2015). ↩

- Zhang Yu, "Tsinghua University Pioneers Total Shift Online amid Coronavirus Epidemic," People's Daily Online, March 6, 2020. ↩

- Bryan Alexander, Academia Next: The Futures of Higher Education (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019), p. 115. ↩

- Paul N. Friga, "Scenario Planning for Coronavirus," Inside Higher Ed, March 13, 2020. ↩

- Robin Cook, Invasion (New York: Berkeley Publishing, 1997), p. 238. ↩

Jude Chudi Okpala is a faculty member in the Department of Philosophy and Classics at the University of Texas at San Antonio. He has taught the "Global Literature" course at Beijing Jiaotong University, Weihai, China, through the Rochester Institute of Technology, Weihai Campus.

© 2020 Jude Chudi Okpala