Despite growing attention to accessibility concerns for students, faculty needs are often not part of those conversations. Faculty with disabilities face a number of obstacles that colleges and universities can address with open, empathetic discussions and actions.

"Institutional support for accessibility technologies" made the EDUCAUSE Top 10 Strategic Technologies list in 2020 for the second year in a row—rising, in fact, from sixth spot in 2019 to second this year—signaling that a critical number of higher education professionals find this issue important.1 Higher education IT organizations are devoting time and resources to planning and implementing solutions that can make their campuses more inclusive, and many of those efforts focus on the needs of students with disabilities. But what about instructors who need disability support? While awareness has increased on many campuses about equity issues related to gender and race in the institutional workforce, faculty with disabilities2 have often been overlooked. In fact, in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Joseph Grigely referred to faculty with disabilities as "the neglected demographic," given that little research exists that sheds light on the size of this group, the types of disabilities they have, and their lives in academe.3

In ECAR Study of Faculty and Information Technology, 2019, Joseph Galanek and I shared what faculty told us about their experiences with the support they received for making their courses accessible to students with disabilities.4 Although we did not ask respondents to identify their disability status, we did ask them to share their experiences and opinions about the technology support their institutions provide for faculty with disabilities.

Services for Faculty with Disabilities

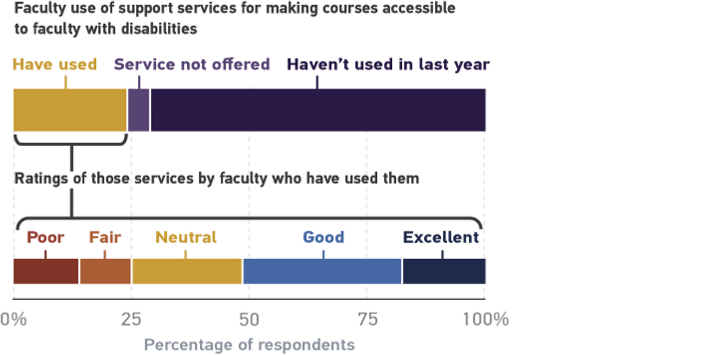

Many instructors with disabilities have specific technology needs for teaching. We asked faculty to rate their experiences with institutional support of such technologies for faculty with disabilities. Although most faculty (71%) told us they had not used these services in the past year, among those who had, only half (52%) said their experiences were good or excellent and one-quarter rated them as fair or poor (figure 1). Clearly the workplace needs of a significant portion of faculty who do use these services are not being met well.

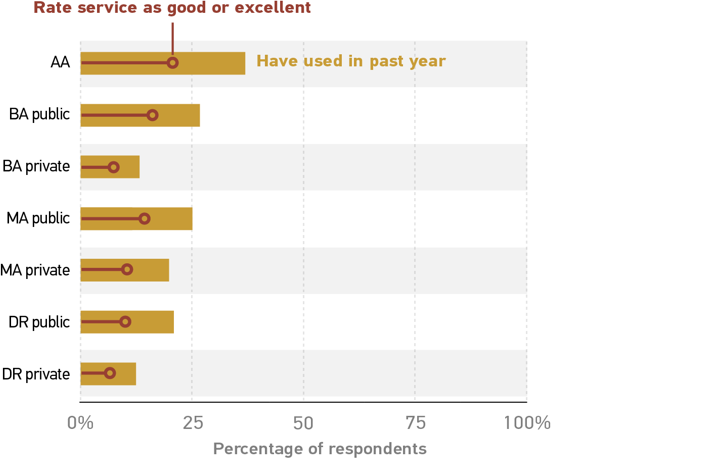

Looking at differences across Carnegie class, we found that significantly more respondents at AA institutions said they had used technology support for faculty with disabilities (37%) and rated those services more highly than respondents at other institution types (figure 2). Furthermore, more AA faculty reported using technology support for making their courses accessible to students with disabilities—and rated these services more favorably—than faculty at other institution types. Community colleges enroll more students with disabilities—larger numbers overall and larger proportions—than public four-year colleges do,5 so instructors at AA schools might have more experience providing assistive technologies and services to students. If faculty members have had positive experiences using technology services to support students, then they might be more inclined to see their institution's culture around disability services in a positive light.

Some sources suggest that faculty underreport disabilities and that, in turn, workplace accommodations go underrequested by faculty. Other data indicate that individuals with disabilities are underrepresented among the faculty ranks.6 Public records indicated that in 2016, just 1.5% of faculty at the University of California, Berkeley identified as having a disability, but it's estimated that 4% of all US faculty have a disability,7 a gap that could be explained by underrepresentation, underreporting, or both. This disparity is even more striking when compared with the general population; the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 19% of the workforce in the United States had a disability in 2019.8

Although we don't know how many respondents in our study have a disability, it's evident that appreciable numbers of faculty are using these services—whatever the reasons. Whether they have disabilities or not, many faculty clearly find such services valuable, suggesting that one need not have a recognized need in order to benefit from expanded technology access.

Disclosure Can Be Risky

For a variety of reasons, faculty, like students,9 might choose not to report disabilities and seek accommodations. Findings from one study that examined disclosure among college and university faculty who self-identified as having mental illnesses or mental health histories revealed that only 3.7% disclosed this fact to their institution's office of disability services.10 Aside from not wanting to disclose a disability, reasons for not requesting accommodations include lack of awareness about available services, a desire for privacy, and the concern that such a request would negatively affect the chances of tenure and/or promotion.11 Research has also shown that many disabled faculty and staff have experienced unwelcoming work environments, from "incivilities" based on ignorance to open discrimination and harassment.12

Some faculty members, however, are comfortable disclosing their needs and talking openly about their disabilities, as it can lead to a greater understanding of the benefits that expanded access can have not just for those with disabilities but for the entire campus community. For example, Assistant Professor Stephanie Kerschbaum, who identifies as a deaf academic, wrote, "I have found that open discussion of my disability and of how I accommodate it in all aspects of my faculty life has led me as well as my colleagues to orient ourselves toward one another in new ways."13 Her colleagues have learned how to work with her to provide what she needs, and she has also experienced how "expanded access" can be universally beneficial. Citing an example of her request for real-time captioning on a large screen at a conference to follow the speakers, she notes, "everyone could read it, not just me."

Still, numerous disability experts recognize that revealing a disability in academia can in many cases be downright dangerous, especially for those who have not achieved a status that affords them the safety "to become not only advocates on behalf of people with disabilities but also forthcoming about their personal lifeways."14 Disclosure can be particularly fraught for adjunct, non-tenure track and junior faculty who lack job security.

Pre-tenure faculty can be at risk because requesting workplace accommodations could be interpreted as an inability to perform on par with colleagues who do not have a disability. Individuals with disabilities can expend significantly more time and energy than their peers in navigating their institution's systems to get the support they need.15 Faculty (or individuals applying for faculty jobs) who use assistive technology might experience difficulty from the very start if an institution's campus website is not designed for accessibility. Even after workplace accommodations are in place, many faculty must go through additional labor-intensive steps to use assistive technology services and tools. For example, screen-reading software, which is used by individuals who are blind or those with low vision, cannot fluently read PDF text that isn't properly formatted; as a result, the user hears the text as "strings of babble," requiring added work from the user to try to make sense of the PDF content. Producing text might also take more time for faculty with limited mobility who use speech-to-text programs for their writing, computing, and research. And faculty who manage symptoms related to chronic illnesses or other health conditions might need more flexibility to meet tenure milestones.16

Non-tenure track and adjunct faculty also experience many of the aforementioned challenges; however, due to the precarity of their contracts, they can be even more vulnerable if they disclose a disability or request accommodations. In general, institutions are not obligated to rehire non-tenured faculty at the end of their contract period. Instructors whose needed accommodations are perceived as costly or troublesome might not be invited back at the end of the term, and no reason would need to be given. Some adjunct faculty opt to get the necessary technology support outside their institutions or simply go without, rather than risking disclosure. In an interview with Chronicle Vitae, retired adjunct professor Brian Kruse, who is blind, talked about the powerful technology he used for his teaching that allowed him to read texts, create lesson materials, and grade in real time. But as an adjunct, "he didn't dare ask for an accommodation" and opted to get support outside the university.17 As disability scholar Ellen Samuels has said, "We must constantly weigh our access needs against the very real risk of being perceived as demanding and expensive troublemakers in a professional landscape shaped by expectations of gracious collegiality."18 Moreover, regardless of their rate or rank, faculty who file disability discrimination suits against their institutions have been historically unsuccessful, leaving faculty who pursue accommodations or support services with little recourse.19

The Challenge of Requesting Accommodations

Faculty members who do decide to disclose a disability and seek workplace accommodations can face additional challenges in tracking down the resources they need. On many campuses, it's not entirely clear where one should go first, as much of the public-facing information about disability support in higher education is directed toward students. Information expressly for faculty with disabilities can be difficult to find on some institutional websites, if it exists at all. Disability offices at most colleges are centralized and serve only students, while services for employees are often dispersed among different departments and units (e.g., Human Resources, Americans with Disabilities Act coordinators, Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action and/or diversity offices). Most faculty with mental disabilities are not aware of the services available to them and are rarely given information about applying for accommodations.20 Searching for support services can feel like a second job that forces them to reveal confidential health information numerous times.21

On some campuses, faculty members must request and then negotiate workplace accommodations through their direct supervisor or department chair, which could mean disclosing private medical information with a person who (1) may have no understanding of or expertise with disability and (2) can influence decisions related to tenure, promotion, rehiring, salary, and scheduling.22 The power differential inherent in such a structure can compromise confidentiality and is also a barrier that discourages individuals who need accommodations from requesting them.

Improving Support for Faculty with Disabilities

If "institutional support for accessibility technologies" is indeed important to colleges and universities, then the support of faculty with disabilities is a critical part of this commitment. To better serve faculty with disabilities, colleges and universities can take the following actions:

- Develop and implement campus accessibility standards following Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). Individuals with disabilities, particularly those who use assistive technology, will have greater access to web resources and applications when these standards are met, which in turn can reduce the need for formal workplace accommodations and support requests.

- Routinely assess faculty technology usage to identify access gaps, and establish alternate access paths for individuals who need them.

- Encourage accessibility as a general campus topic to demonstrate it is an institutional responsibility. To foster inclusive environments, institutional leaders should make accessibility a part of every conversation, and it should have a "daily presence,"23 from planning faculty training materials to organizing events. Such an approach can cultivate cultural change while minimizing the need for faculty members with nonapparent disabilities to disclose them.

- Fund, from a central source, the accessible and assistive technology that instructors need; this will help curtail not only discrimination in hiring/rehiring and promotion but also resentment from other faculty members.24

- Establish a peer community to address accessibility issues on campus and offer disability advocates a seat at the table.25 Connecting directly with disabled colleagues as they navigate campus systems and use the tech tools provided by their institutions offers opportunities to improve access and support services for these individuals, much like it did for one faculty member at Elgin Community College.26

- Create a centralized organizational structure for disability support services, ideally in a single office (such as the University of Minnesota's Disability Resource Center), so that faculty with disabilities do not have to directly negotiate accommodations with supervisors. First steps can include creating a central accessible website that aggregates information about these services, where to go for what, and how to apply for accommodations so that employees don't have to go through numerous channels.

- Partner with other campus stakeholders such as Human Resources, teaching and learning centers, Americans with Disabilities Act/Section 508 coordinators, disability services offices, health care centers, and disciplinary departments to spread the word about faculty accessibility resources. Sharing this information in employee onboarding and orientations, as well as in instructional design and faculty development workshops, offers additional opportunities to assist faculty with the tools they need to be their best at their jobs.

Taking these steps makes resources and support more accessible to faculty with disabilities and fosters a more inclusive culture on college and university campuses.

For Further Reading

- Alice K. Adjunct, "The Revolving Ramp: Disability and the New Adjunct Economy," Disability Studies Quarterly 28, no.3 (Summer 2008).

- Susan Cullen, "Accessibility: A Shared Campus Responsibility Best Accomplished with Executive Support," EDUCAUSE Review, January 29, 2018.

- Wendy S. Harbour, "Final Report: The 2004 AHEAD Survey of Higher Education Disability Services Providers" (Waltham, MA: The Association on Higher Education And Disability, 2004).

- Nigel Lockett, "Disability on Campus: ‘I Have Decided to Go Public as the Dyslexic Professor,'" Times Higher Education, May 15, 2017.

- Katie Rose Guest Pryal, "Rough Accommodations," in Life of the Mind Interrupted: Essays on Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education (Chapel Hill: Raven Books, 2017).

- David Harry Smith and Jean F. Andrews, "Deaf and Hard of Hearing Faculty in Higher Education: Enhancing Access, Equity, Policy, and Practice," Disability & Society 30, no. 10 (2015): 1,521–36.

Notes

- Mark McCormack, D. Christopher Brooks, and Ben Shulman, "The Top 10 Strategic Technologies for 2020," EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR), January 27, 2020. ↩

- Recognizing that identification preferences vary, I use both person-first ("individuals with disabilities") and identity-first ("disabled individuals") language in this article. ↩

- Joseph Grigely, "The Neglected Demographic: Faculty Members with Disabilities," Chronicle of Higher Education, June 27, 2017. See also Kate Sang, "Disability on Campus: The Challenges Faced and Change Needed," Times Higher Education, May 18, 2017. ↩

- Joseph Galanek and Dana C. Gierdowski, ECAR Study of Faculty and Information Technology, 2019, December 9, 2019. ↩

- American Association of Community Colleges, "Students with Disabilities," DataPoints 6, no. 13, September 2018. ↩

- Amir Haji-Akbari, "Disability Parking Spots Yet to Be Filled," Inside Higher Ed, April 9, 2018. ↩

- Grigely, "The Neglected Demographic." ↩

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics, "Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics Summary," Economic News Release, February 26, 2020. ↩

- Dana C. Gierdowski, ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2019, October 30, 2019. ↩

- Margaret Price, Mark S. Salzer, Amber O'Shea, and Stephanie L. Kerschbaum, "Disclosure of Mental Disability by College and University Faculty: The Negotiation of Accommodations, Supports, and Barriers," Disability Studies Quarterly 37, no. 2 (2017). ↩

- Keren Dali, "The Lifeways We Avoid: The Role of Information Avoidance in Discrimination against People with Disabilities," Journal of Documentation 74, no. 6 (2018). ↩

- Elizabeth Pain, "Survey Highlights the Challenges Disabled Academics Face—and What Can Be Done to Address Them," Science Magazine, May 15, 2017; Cheryl L. Shigakia, Kim M. Anderson, Carol L. Howald, Lee Henson, and Bonnie E. Gregg, "Disability on Campus: A Perspective from Faculty and Staff," Work 42, no. 4 (2012). ↩

- Stephanie L. Kerschbaum, "Access in the Academy," Academe, September–October 2012. ↩

- Keren Dali, "The Right to Be Included: Ensuring the Inclusive Learning and Work Environment for People with Disabilities in Academia," Information and Learning Science 119, no. 9/10 (2018); Dali, "The Lifeways We Avoid" (quote); Katie Rose Guest Pryal, "Disclosure Blues: Should You Tell Colleagues about Your Mental Illness?" in Life of the Mind Interrupted: Essays on Mental Health and Disability in Higher Education (Chapel Hill, NC: Blue Crow Books, 2017). ↩

- Pain, "Survey Highlights the Challenges Disabled Academics Face." ↩

- Stephanie L. Kerschbaum et al., "Faculty Members, Accommodation, and Access in Higher Education," Profession (December 2013). ↩

- David Perry, "Accommodations in Academia," Chronicle Vitae, March 21, 2016. ↩

- Kerschbaum et al., "Faculty Members, Accommodation, and Access in Higher Education." ↩

- Suzanne Abram, "The Americans with Disabilities Act in Higher Education: The Plight of Disabled Faculty," Journal of Law & Education 32, no. 1 (January 2003). ↩

- Price, Salzer, O'Shea, and Kerschbaum, "Disclosure of Mental Disability by College and University Faculty"; Katie Rose Guest Pryal, "On Faculty and Mental Illness," Chronicle Vitae, December 19, 2017. ↩

- Pain, "Survey Highlights the Challenges Disabled Academics Face." ↩

- Dave Fuecker and Wendy S. Harbour, "UReturn: University of Minnesota Services for Faculty and Staff with Disabilities," New Directions for Higher Education, no.154 (Summer 2011); Grigely, "The Neglected Demographic"; Margaret Price and Stephanie L. Kerschbaum, "Promoting Supportive Academic Environments for Faculty with Mental Illnesses: Resource Guide and Suggestions for Practice" [http://tucollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Faculty-with-Mental-Illness.pdf], Temple University Collaborative (January 2017). ↩

- Grigely, "The Neglected Demographic." ↩

- Price and Kerschbaum, "Promoting Supportive Academic Environments for Faculty with Mental Illnesses" [http://tucollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Faculty-with-Mental-Illness.pdf]. ↩

- See Yvonne Tevis, "Adapting Technology and Building an Accessibility Community at the University of California," EDUCAUSE Review, March 25, 2019. ↩

- Michael Chahino, "Technology Innovations on Campus Can Open the Door to Accessibility for Individuals with Disabilities," EDUCAUSE Review, July 10, 2019. ↩

Dana C. Gierdowski is a Researcher at EDUCAUSE.

© 2020 Dana C. Gierdowski. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.