Research at the University of Nevada into how students, faculty, and staff have responded to the pandemic reveals some overlapping and divergent concerns, and it provides insights into steps institutions can take to meet the needs of campus communities.

"Working online all the time is tiring and feels a little bit soul-destroying at times. I miss having face-to-face interaction with my students." —Academic Faculty

The "Drive to Digital Transformation"1 was immediate and omnipresent in March as the University of Nevada, Reno, like most other institutions in the country, transitioned to remote work, instruction, and learning. Actually, it was less a transformation than a massive traffic jam, with everyone exiting campus. Faculty and staff rose to the challenge, going above and beyond what was expected, and students adjusted, sort of. As it became clear that this pandemic was here for an extended stay, we wondered what adjustments to remote life were needed. What was working well, and what needed more attention?

To glean insights that would assist in determining next steps, we developed four surveys, to be run concurrently, to capture the perspectives of undergraduate students, graduate students, academic faculty, and administrative faculty / classified staff—four views of the same moment for a university in the midst of a pandemic-triggered digital transformation. The survey revealed some expected results:

- Students and employees preferred—and missed—the on-campus face-to-face experience.

- A large percentage of students expressed anxiety about their academic performance.

- Faculty were concerned about how well their students were learning in the make-do remote environment.

- A positive correlation emerged between higher ages (or years of experience) and the ability to adjust to the exigencies of pandemic life.

But beneath those fairly predictable results we found connections between factors that may make a technology-mediated life more workable or less workable. The positive and negative correlations we found are not new to people in the business of online education and remote work. The more surprising outcome may be that our traditional, residential, public, land-grant research university weathered a dive in the deep end of all-online interaction, though not without some bruises. The data collected indicate issues in both our infrastructure and the way we do things. These issues are not irreparable. We suspect and hope the same has been true for most in higher education. In Nevada, the spring semester of 2020 ended with student achievement and employee productivity largely unharmed.

Survey results provided immediate feedback on needed improvements going into the fall 2020 semester, as well as considerations for the future beyond this profound health crisis. Some adjustments can be made within our own technology operations. Others need the combined effort of multiple players across campus. For instance, we found a positive correlation between student anxiety and difficulty getting useful information about some university services, such as financial aid or mental health. This represents another of those "common sense" realizations: as anxiety increases, so too does frustration with navigating websites, using collaboration software, and sorting out contradictory advice.

We took a step back to identify what information got through to students and examine its usefulness. Survey responses lent insight into immediate concerns that have long-term impact. We found clear differences—based on academic level—in students' ability to adapt to changing circumstances. Might one direction be, as Bowdoin College has determined for the fall 2020 semester, to limit the on-campus experience to first-year and transfer students while instruction for upper-level students is focused online? Beyond the pandemic, might this be a model to embrace for the longer term?

Similarly, the data collected from employees identified some immediate actions that could improve remote work. Although the majority of faculty and staff reported that they were managing to continue working despite the challenges, notable issues were identified concerning the quality of home workstations and peripherals. If the university were to embrace longer-term operational changes toward remote work, would that include investment in dual workstations, one for campus and one for home? Or perhaps a different architecture is more appropriate, a return to the days of a thin, inexpensive client connected to a powerful server—oh, wait, isn't that the cloud world we already more or less inhabit?

The title of the Alan Watts book "Cloud Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown" may be an appropriate mantra for lessons learned during the days of COVID-19. We've only begun to mine the data we collected. Most of our time is spent trying to stay ahead of the continuously changing circumstances of the pandemic. This article outlines what we did, what we observed, and what we've begun to consider that the data is telling us. If others have done similar surveys, we'd like to share and compare results.

Survey Methods, Measurement, and Analytical Approach

Using sample questions drawn from the EDUCAUSE DIY Survey Kit: Remote Work and Learning Experiences, we developed four versions of a remote working and learning survey. The questions were adapted to the environment at the University of Nevada, Reno. A separate survey was drafted for each of four main cohorts: undergraduate students, graduate students, academic faculty, and administrative faculty / classified staff. The drafted questions were sent to several campus constituents for review and refinement. The surveys were administered over a two-week window, from April 24 through May 8, 2020 using Qualtrics survey software.

Participation

We invited 16,120 undergraduate students, 3,637 graduate students, 2,600 academic faculty, and 2,700 administrative faculty and classified staff to take the survey through an anonymous link distributed by email. Table 1 displays the participation rates, which vary between 21% and 47%.

Table 1. Survey participation rates

|

|

Population | Participants | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Undergraduate Students |

16,120 |

3,333 |

21% |

|

Graduate Students |

3,637 |

771 |

21% |

|

Academic Faculty |

2,600 |

730 |

28% |

|

Administrative Faculty / Classified Staff |

2,700 |

1,270 |

47% |

For undergraduates only, participation by academic level was self-reported within the survey. Roughly equal proportions participated across academic levels: 26% first-year students, 20% sophomores, 30% juniors, and 24% seniors.

Measurement and Analytical Approach

For the analysis of the undergraduate and graduate student surveys, the primary outcome of interest was the students' concern with their academic performance during the spring semester. Concern with academic performance was measured on a 5-point scale of increasing concern (1 = not at all concerned, 5 = very concerned). Roughly 39% of all students, both graduate and undergraduate, were very concerned, 21% a lot concerned, 20% moderately concerned, and 19% a little or not at all concerned.

The student surveys (both undergraduate and graduate) had four sets of conceptual question blocks or series. Measurement of three of the series were on a five-point scale, but the fourth series—on access to technology—was on a 4-point scale. For the blocks of questions about the students' motivation and perceived support by instructors, items reflect agreement from strongly disagree to strongly agree and include a neutral middle point (scale 1–5). For the question block on the students' concern about opportunities to interact, items reflect increasing sentiment from no concern to a great deal of concern (scale 1–5). For the question block on the students' evaluation of access to library resources and technology, the items reflect an increasing scale from terrible to excellent access (scale 1–4).

Each series in the student surveys was analyzed using factor analysis (available upon request). Four factors were identified:

- Factor 1: Lost interactions captures the students' sentiment that they have fewer opportunities to interact with peers or faculty in both learning and extracurricular settings.

- Factor 2: Motivation captures the students' perception of their ability to learn or focus during remote instruction and interaction.

- Factor 3: Instructional support expresses the students' evaluation of the responsiveness, communication, and support of their instructors overall.

- Factor 4: Access to technology expresses the students' evaluation of their remote access to library resources and technology services.

The surveys for academic faculty and the administrative faculty or classified staff were much more simply structured and not designed to capture underlying constructs or degree of impact. Those surveys collected information by means of lists, with the option to select all that apply from each list. For example, participants were asked to select from a list of technological issues those that they were experiencing. As such, percentages were examined, but no further analytical approaches were applied to the data.

Survey Insights

We organized our survey insights into two topics for this article. The first topic focuses on perceptions students and faculty had of opportunities to interact remotely and how this relates to student motivation and academic performance. The second topic focuses on perceptions of instructional support, as well as access to information and technology. Although the data is correlational, we impose a causal relationship on the narrative primarily because both faculty and student comments imply such—specifically, comments suggest that motivation and performance are lower because the quantity and quality of interactions have fundamentally changed; likewise, performance is lower where students perceive less support, information, or access to technology. We did not structure the survey to capture causality, so we leave it open to debate.

Topic 1: Opportunities to Interact, and Student Motivation and Performance

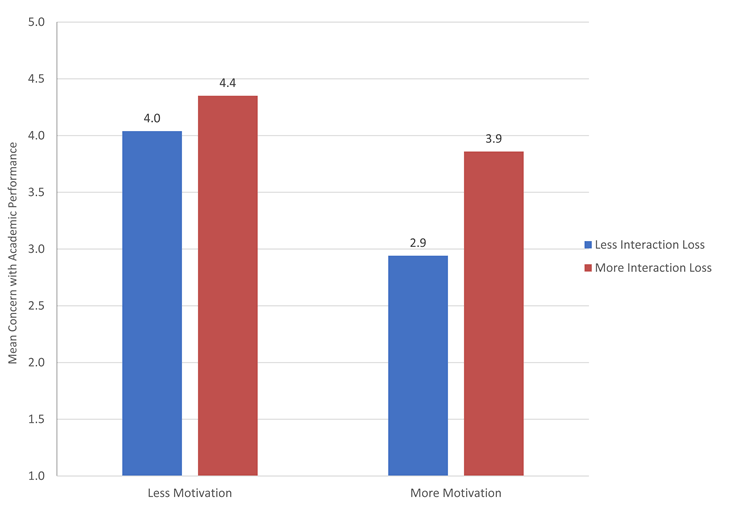

Figure 1 shows that concern with academic performance was greatest (mean of 4.4 on the 5-point scale) among students who had less motivation and perceived more lost opportunities to interact as a result of the pandemic. In contrast, concern was 1.5 points lower (mean of 2.9) among students who had more motivation and perceived fewer lost opportunities to interact. The important takeaway here is that both internal drive and a need for social interactions appear to be important contributing factors to academic performance.

"Losing the personal touch with students being able to interact with them. Students reported that they liked the activity, but they missed the classroom interactions we were having." —Academic Faculty

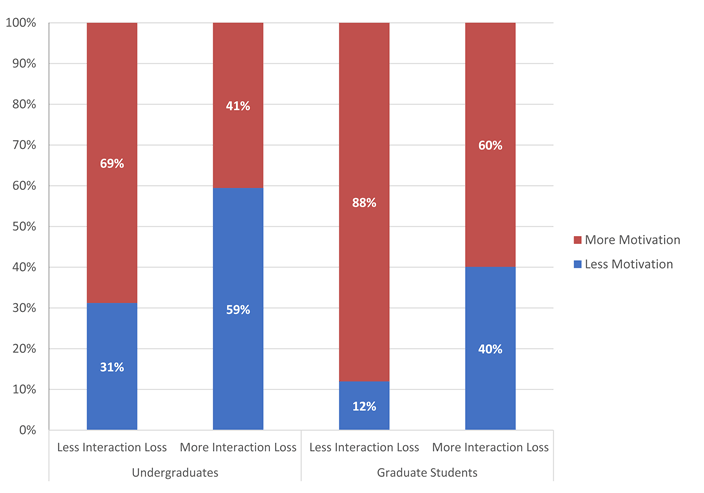

Figure 2 reveals the relationship between the perception of opportunities to interact and student motivation. Both undergraduates and graduate students who perceived more lost interactions had significantly less motivation (a drop of 28 percentage points for each group). Graduate students reported higher motivation overall, yet a greater loss of interactions resulted in a tripling of the number of graduate students who felt less motivated, compared to a doubling of undergraduates who felt that way. In the words of undergraduates:

"I have one class doing all asynchronous coursework, and that makes it difficult to have interaction with others in my class. It would be nice to 'meet' online, even in chatroom style, at least once every other week. Just for the connection with others." —Graduate Student

"It's just not working for me. We are in a global emergency, and I understand we can't just not go to school. But I am so easily distracted, and my professors are giving me loads of busy work with not enough time to complete it. I have lost all means of motivation and have no energy to do this work." —Undergraduate Student

"Overall, I am a visual learn[er] that likes to interact in person. There is really nothing that remote learning can do for me. I automatically have less motivation, am distracted, especially when you're in a big family and my environment is loud." —Undergraduate Student

Undergraduates tend to be younger and have less experience living independently than graduate students. Our interpretation is that academic level may be a proxy for experience, especially the kinds of experiences that would help a person manage a drastic change in the organization of social life. High levels of inexperience can manifest in poor communication and thereby poor interactions, decreased motivation, and lower performance.

Communication, in particular, was a big concern of academic faculty. Nearly 35% reported they were not able to communicate effectively to advise students, 22% reported that students were not adequately available or responsive remotely, and 43% believed students were struggling with learning remotely. In fact, 52% of academic faculty identified diminished student learning as their main concern.

In contrast to their working with students, many academic faculty were prepared to collaborate remotely to continue their research because research often necessitates collaborative work across institutions or between institutions and government agencies.

"I am having very few challenges at the moment, but that is because I already managed several large research groups that span multiple universities, so we were already familiar with collaborating via video conferencing and online data sharing services. If I had needed to ramp up this operation overnight, my answers would have been very different." —Academic Faculty

Administrative faculty and classified staff transitioned to interacting and communicating remotely better than many expected.

"I feel well connected and supported by my supervisor and coworkers. Work is a little slower because my personal computer does not have the same power capacity as my work PC. Also, having all family at home is more distracting as I don't have designated office area. I move some of my work that requires concentration to late evening hours." —Administrative Faculty / Classified Staff

Meanwhile, the lost interactions with students left some staff wondering what work they were supposed to be doing and how.

"It's frustrating when you are told to work remotely and do not know what work needs to be done when a large part of your job is interacting in person with people."—Administrative Faculty / Classified Staff

Lost opportunities to interact were not limited to instructional settings; students also reported issues with access to co-curricular services such as financial aid and mental health services. Table 2 shows that more than half of the students who attempted to access services for mental health or financial support had problems.

Table 2. Have you been able to access the following services remotely?

| Type of Service | Of those who attempted to access service, percentage who had problems |

|---|---|

|

Emergency Financial Support |

60% |

|

Mental Health Services |

53% |

|

Career Services |

46% |

|

Tutoring Center |

44% |

|

Health Services |

43% |

|

Math Center |

39% |

|

Writing Center |

34% |

|

Academic Advising |

29% |

|

Library Services |

28% |

|

Information Technology Services |

26% |

"My biggest issue with remote learning is staying motivated and focused on classes and dealing with the mental health repercussions of being stuck in one place all day. I haven't yet felt the need to reach out to counseling services for help, but I know several people who relied on campus counseling services who aren't able to receive the same support now that they needed before we went online. Something needs to be done to ensure that these students are having their needs met and aren't being ignored by the university's system of support." —Undergraduate Student

Although it was not a prevalent issue, faculty also expressed considerable anxiety and stress due to the transition. Most often their feelings were shared as part of their inability to support students, and many indicated substantial increases in workload.

"The transition to all-online course delivery has been harrowing for me, and students email me at all hours of the day/night to ask me to fix technological issues or improve their experience somehow. It absorbs all of the energy I have left to help them. I have had two panic attacks since Spring Break, despite never having a history of panic attacks or anxiety before." —Academic Faculty

"The college has been supportive, and we are working to resolve most of my issues for this semester. The biggest problem is that we could not prepare for this change, so we are all adapting in real time. That is no one's fault, but it has significantly increased my workload, so I am working many more hours than I was before. Recognizing that many faculty, especially instructors, are working more than usual and modifying expectations accordingly would help." —Academic Faculty

Topic 2: Impact of Instructional Support and Access to Technology

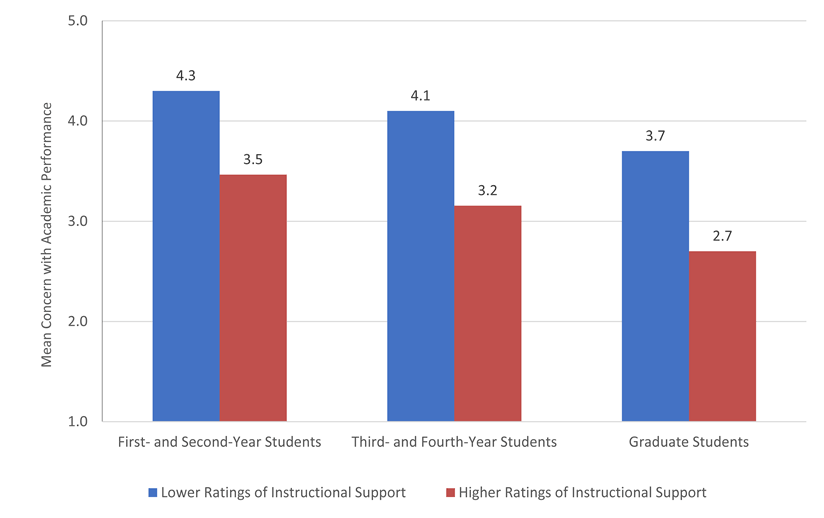

Figure 3 shows that student concern with academic performance is much higher for students who gave lower or more negative evaluations of instructional support; likewise, it is slightly higher for first- and second-year students than for third- and fourth-year or graduate students. Even among students who reported better ratings of instructional support, the average for academic concern was near the midpoint of the scale. In other words, even with good instructional support, students were still moderately worried about their performance.

About 29% of academic faculty reported that their course lessons or activities did not translate well to a remote environment. In the comment section of the academic faculty survey, a few respondents identified particular activities that rely on sustained interaction and discussion to achieve learning and that did not work well remotely:

"There is no way to replace the in-person classroom environment for discussion courses where the learning emerges from shared realizations and energies in the classroom; feelings/mood/environment and the energy of people sharing the same space [are] vital to the type of learning my students receive—which they cannot get online." —Academic Faculty

"Transition to simulating real-life clinical experiences has been very time-consuming for faculty and challenging for students. All other course assignments have translated well to online environment." —Academic Faculty

Faculty need more training and more time to creatively adapt their activities. For those who were prepared ahead of time, the transition mid-term went much easier:

"Fortunately I have taken several workshops on campus related to online teaching and learning, and this knowledge helped me to adapt quickly to provide course content to students." —Academic Faculty

"Adaptation to an online format is extremely time-consuming, and I easily spend 3-4 times as long to prepare materials, etc. as I normally do. Exams are extremely difficult to design and administer, especially in the sciences (i.e., mathematics), and proctoring is a major issue." —Academic Faculty

As with instructional support, concern about academic performance was much higher among students who gave lower or more negative evaluations of their access to technology and library resources; likewise, concern about performance was slightly higher for first-year students and sophomores than for juniors and seniors or for graduate students.

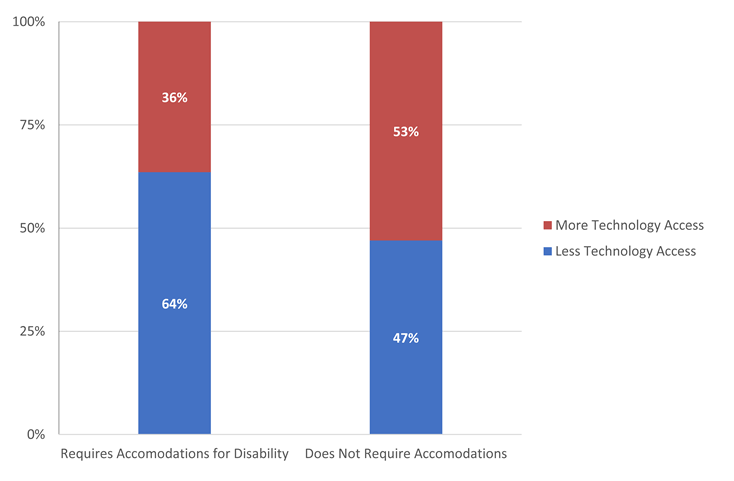

Anticipating problems with technology, we included a survey question that asked students whether they needed technical or teaching-related accommodations under Section 508 of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Ninety-nine students self-identified and then answered a follow-up question focused more narrowly on the accommodations that they were having difficulty accessing. Figure 4 shows that a greater proportion of students who require accommodations (64%) than those who do not (47%) indicated they had limited or less access to technology and library resources. Better instructional support in a remote environment will have limited effect on academic performance if students, especially students who need accommodations, have less access to technology or cannot access information.

More than one-quarter (27%) of academic faculty reported that student discomfort or lack of familiarity with technology was a problem, while 19% said their own lack of familiarity was an issue. One academic faculty member noted that students were "just now finally starting to adjust to the online teaching," this after five weeks of remote instruction and two weeks before the end of the term. Additionally, one problem appeared to be access to tools and devices at home that would make teaching and research more efficient, as opposed to familiarity with their use. When asked if they were having challenges in adapting course design and or assignments to remote work, only 6% of academic faculty reported "I am not familiar or comfortable with online applications/tools." Instead, 32% indicated they do not have access to additional computer monitors, 17% reported that they do not have communication equipment (headset, microphone, camera, etc.), and 14% indicated that software access was a challenge.

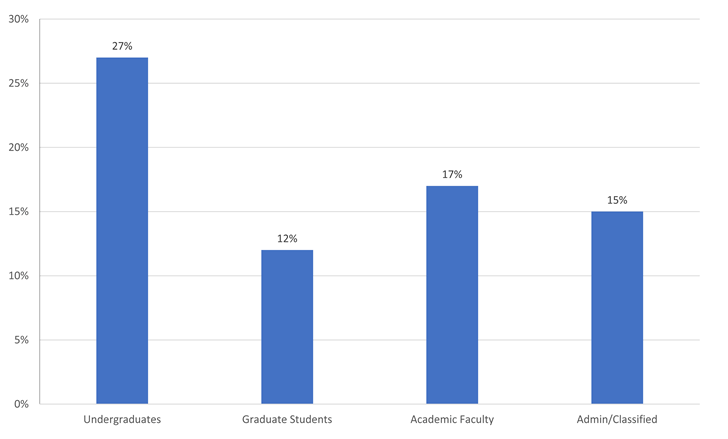

From the very beginning of the transition, the university provided access to laptops for free and encouraged staff to take office equipment home. Likewise, the university was able to make strides toward improving access to auxiliary devices and training on how to use devices and software for remote work. Unfortunately, access to reliable internet service to support remote connectivity remained an issue for a not-insubstantial portion of all stakeholders. Figure 5 shows the percentage of respondents across surveys who reported poor or terrible internet access in their off-campus environments.

For the most part, faculty and students recognized that although some elements of the remote experience could be controlled, other elements could not. Time will tell whether this understanding continues into the fall term.

"If this did go on into next fall, it could be nice to consider adjunct scholars; we have little funding and are not provided with computers or any equipment. I bought two webcams for moving online…I use my own laptop, which seems strained by the two cameras. I use my own internet, which also seems a bit strained by using Zoom, and I wish I had a higher broadband. This is all fine currently, but as I say, if we do move regular classes online again in future, it would be great to consider equipment needs for adjuncts as a standard thing (rather than a 'let us know if you have an emergency need' thing)." —Academic Faculty

Finally, the student surveys captured environmental issues related to access to food and housing. Because food and housing insecurity have been a focus on our campus for several years, we asked students if they were having such difficulties. Forty-four percent of the undergraduate students and 33% of the graduate students indicated they were having a moderate level to a great deal of struggle paying rent or buying food. Fundamental needs must be met before real learning can take place. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on unemployment makes the situation much worse, with many students struggling to meet their basic needs and unable to ask family or friends for help. For one respondent, the cumulative impact of food, housing, health, and family problems makes this situation a tragedy:

"A lot has to do with my home environment. That is something the university can't fix. But financially I am struggling, can't finish paying off tuition, rent, buy food." —Undergraduate Student

From Insight to Action

What does the data from our four surveys tell us? Well, for one thing, we all survived. The semester concluded. Students moved forward in their academic careers, and many graduated, albeit into an uncertain world. The work of the university—teaching, research, public service—continued, modified to meet the circumstances. A comparison of student grades for the spring 2020 semester showed a slight rise in overall grade point average compared to spring semester 2019. Was this due to empathetic grade inflation, or did the concern expressed by students for their coursework, coupled with the concern expressed by instructors, contribute to real performance improvement? Answering that question would require more examination. In short, going remote largely worked, but gaps and frustrations were unearthed—some expected, others less anticipated. Those gaps need attention both in the immediate future and, more importantly, in the post-pandemic future.

"I think overall, the university is doing its best. I would argue to continue helping with technologies access and development, helping us figure out ways to keep our students engaged and make sure they're doing okay, and figuring out ways to help with our inability to continue with lab research for the time being." —Academic Faculty

As anticipated, the surveys reinforced the fact that, across all four cohorts, a majority of respondents miss and prefer the on-campus experience. Among the four groups, the administrative and classified staff appeared to have the easiest time with the transition to remote work. Is this something to consider for the longer term? The tendrils of such an institutional move reach into many areas. What accommodations need to be made for large numbers of employees working remotely? How might this affect the planning for on-campus working spaces for employees? Should the institution take a more nuanced approach to determine which students should be given priority for on-campus life while others have more options for remote academic work?

Clear and unsurprising results from the survey indicated a connection between academic level and difficulties dealing with stay-in-place directives. Perhaps, both in the near-term semesters still under the pandemic cloud and for the campus of the future, residency might be a priority for first-year students and those involved in fields of study not lending themselves to a virtual experience.

Some of the gaps exposed by the survey seem less affiliated with doing things remotely than with the effective use of and training with technology and procedures. So called "remote" technology is now more commonplace with the Internet of Things and the proliferation of smart devices. People are using the same technology whether separated by fifty feet or fifty miles.

A focal point is the ability—even when technology is the mediator for all interactions—to interact as unencumbered as one might be when calling across the cubicle to a colleague or meeting someone for coffee in the student union. Nothing can entirely replace face-to-face interaction, but can enough of that be recreated virtually for large portions of university life?

As one would expect, people in all four surveys expressed substantial concern around the difficulties of replacing quality in-person interaction. Some of this dissatisfaction was expressed through comments about instructors and supervisors whose style of remote interaction was perceived as overbearing and micromanaging. Did the technologies at play contribute to this anxiety? It seems from the survey data that any technology glitch that impeded communication flow increased the difficulty and unease dealing with remote life. Lost interactions due to poor network connections, difficulty using remote access to applications and desktops, and unfamiliarity with digital collaboration tools all contributed to an unhappy experience for many. Some of these things we can solve, such as by providing a simple-to-use, unified view of services from which students and employees can work. Other concerns, such as the high percentage of undergraduate students who had concerns about having enough to eat, require our attention in concert with our campus and community partners to solve. Being hungry trumps concern over most everything else.

"A great deal of us are struggling to do well in class, get groceries, and pay rent. We, as a university community, should do everything in our power to make students the number-one priority, considering we spend so much money." —Undergraduate Student

At the same time, notable numbers of respondents found the situation workable. Those experienced with learning at a distance took the changes in stride. Some research paused, but the majority of faculty indicated they were able to carry on their research-related work within the boundaries enforced by the virus. Administrators and support staff indicated, overall, that they were able to continue their work. Among this cohort, 87% indicated they were able to maintain connections with colleagues moderately to very well, with the majority (57%) choosing "very well."

What the data from our survey shows, and what we imagine most of us in higher education experienced in Nevada, is that, yes, by and large, we can work and learn and be productive in place, wherever that place might be. Our current technologies enable us to interact with geographical location as a secondary (if that) concern. Certainly, areas of cyberinfrastructure need improvement. The functional processes in place need tweaking. The technologists and the instructors, researchers, support staff, and administrators need to work together to reduce the barriers to carry on the essential business of postsecondary education, research, and public service. Some things, such as affordable and accessible broadband to the home, is a larger national issue, one in which the higher education community can, and should, play an active role.

These are basically tactical concerns for both meeting the immediate challenges of pandemic life and investing in cyberinfrastructure and services past COVID-19. The more difficult question we must grapple with is determining how we all want to interact with one another. When is remote simply not sufficient? What are we losing and what are we gaining as we work and learn in place? These issues force us into questions of value, the value of face-to-face versus remote. They are forcing institutions and systems to decide where to land on the continuum from all in-person to all online. And inevitably the bottom line comes in—what are the costs, what are the benefits?

Our survey doesn't answer those questions, but it certainly invites them. A decade ago, we doubt we could have pulled off an abrupt shift to all online work and instruction at the University of Nevada, Reno. The technologies and the processes just weren't in place as they have been for this extraordinary time. Also, we conducted the survey during the start of the pandemic, when it was still new for everyone. If we conducted the same survey now, our findings could be very different, as everyone has adjusted to the "new normal." We are all still on this voyage across uncharted waters caused by a worldwide health crisis. Eventually we will land at the shore of a place where masks and six feet of separation are no longer needed. How then will we proceed? Now that we are working where we live, we are also living where we work. Do we want our lives so tangled, so technologically integrated that there is little separation between work and home, school and social life?

"I always separated home from work. That is not now possible, and my research productivity has suffered." —Academic Faculty

"I have enjoyed working from home. My job is easily done remotely and with technologies such as Zoom and messaging, I have kept in contact with my team and coworkers. In fact, I would say that there are some coworkers I have spoken to even more than in an office setting. It is nice to experience a job from your own environment. I would like to continue remote work, even part time when this is over. It is productive and an easy transition for my duties." —Administrative Faculty / Classified Staff

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their thanks to Winnefred Rusanoff for her assistance in putting this article together.

Note

- Susan Grajek and the 2019–2020 EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel, "Top 10 IT Issues, 2020: The Drive to Digital Transformation Begins," EDUCAUSE Review, January 27, 2020. ↩

Jennifer L. Lowman is Director, Student Persistence Research at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Burcak Erenoglu is Project & Program Manager, Office of Information Technology at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Angela R. Rudolph is Communications Specialist, Office of Information Technology at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Steve Smith is Vice Provost and CIO at the University of Nevada, Reno.

© 2020 Jennifer L. Lowman, Burcak Erenoglu, Angela R. Rudolph, and Steve Smith. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.