Today's disruptive shifts call for a revolution in educational objectives to accommodate six decades of employment requiring a lifetime of learning.

Profound changes in underlying technology (digitization), in combination with root and branch organizational adaptation (reengineering, or what is often called "digitalization"), have altered the global, socioeconomic environment. These forces of change and adaptation have produced what we are calling "the synergistic digital economy." Students and workers in the synergistic digital economy no longer expect that their jobs will represent a progression through a single career during a lifetime. They instead expect that their current job or career will, at some point, disappear or evolve, forcing them to prepare for novel jobs in several new careers at unpredictable points throughout their lives. The requirement to prepare for a lifetime of changing employment is not optional.

After decades of procrastination, higher education has finally been spurred, by the necessity of the COVID-19 pandemic, to enter the 21st century and offer online courses tailored to the needs of the synergistic digital economy for nontraditional students across a spectrum of ages and career stages. However, we worry that the forced migration to online education could end up as a threat to further progress unless change-resistant nostalgia for the historic model is replaced by a strategic response geared toward and welcoming future evolution.

In our recent book The 60-Year Curriculum: New Models for Lifelong Learning in the Digital Economy, we argue that these disruptive shifts in higher education and in working lives require a revolution in educational objectives. Our book title comes from a term first coined by Gary Matlin, dean of the Division of Continuing Education and vice provost of the Division of Career Pathways at the University of California, Irvine. The "60-Year Curriculum" (60YC) refers to a new perspective oriented toward continuing education and centered on six decades of employment, requiring a lifetime of learning in the context of repeated occupational change and transition.1

In our judgment, the suggestiveness of this term is very powerful, and the elaboration of this perspective underscores the need for a reevaluation of the nature and purpose of higher education. The importance of the shift in point of view was highlighted in a 2012 report by the US National Research Council. Education for Life and Work posited that flexibility, creativity, initiative, innovation, intellectual openness, collaboration, leadership, and conflict resolution are essential skills for each person to have.2 Yet these are not currently a major focus of higher and continuing education.

Forces Driving Change

The World Economic Forum's Future of Jobs Report 2018 described a new human-machine frontier within existing tasks:

Companies expect a significant shift on the frontier between humans and machines when it comes to existing work tasks between 2018 and 2022. In 2018, an average of 71% of total task hours across the 12 industries covered in the report are performed by humans, compared to 29% by machines. By 2022 this average is expected to have shifted to 58% task hours performed by humans and 42% by machines. In 2018, in terms of total working hours, no work task was yet estimated to be predominantly performed by a machine or an algorithm. By 2022, this picture is projected to have somewhat changed, with machines and algorithms on average increasing their contribution to specific tasks by 57%. For example, by 2022, 62% of organization's information and data processing and information search and transmission tasks will be performed by machines compared to 46% today. Even those work tasks that have thus far remained overwhelmingly human—communicating and interacting (23%); coordinating, developing, managing and advising (20%); as well as reasoning and decision-making (18%)—will begin to be automated (30%, 29%, and 27% respectively). Relative to their starting point today, the expansion of machines' share of work task performance is particularly marked in the reasoning and decision-making, administering, and looking for and receiving job-related information tasks.3

Similar conclusions about the challenge of technology-driven career growth and career change are reached in 2019 reports from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Southern Regional Education Board.4 The impact of the pandemic is now accelerating this shift.

Meanwhile, the Brookings report Automation and Artificial Intelligence indicates that almost no occupations will be unaffected by artificial intelligence (AI) and that about one-quarter of US jobs will face high exposure to automation in the coming decades.5 In response, the authors recommend five major public policy agendas; the two closely related to this article are to promote a constant learning mindset and to create a universal adjustment benefit to support all displaced workers. The latter could be actualized through federal initiatives such as employability insurance, which could serve as a potential funding source for the 60YC.

As Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo have noted, AI focused on automation reduces employment, but AI focused on new tasks where labor can be productively employed may increase jobs and develop new types of meaningful work. A crucial issue here is applying AI to create a division of labor in which mid-range and lower-range jobs are worthwhile and respected as opposed to making people the eyes and hands of machines that govern their behavior.6

Education is our most powerful lever for systemically shaping the future. However, typical courses at every level are often shaped by one-size-fits-all presentational/assimilative instruction. Curriculum standards are filled with data that is easy to memorize and measure but useless in a world of search engines. In a system dominated by drive-by summative assessments, students cannot learn capabilities and dispositions vital for the disruptions they must overcome. Strengths such as resilience, perseverance, collaboration, conflict resolution, and forging opportunity from uncertainty cannot be attained in classrooms where compliance and not-making-waves are the central behaviors demanded from instructors.

As for measuring success by high-stakes tests, such an approach prepares students for jobs that will be deskilled by AI. Instead, students should learn what AI cannot do, thus preparing themselves for roles upskilled though intelligence augmentation (IA).7

Implications for Curriculum and Instruction

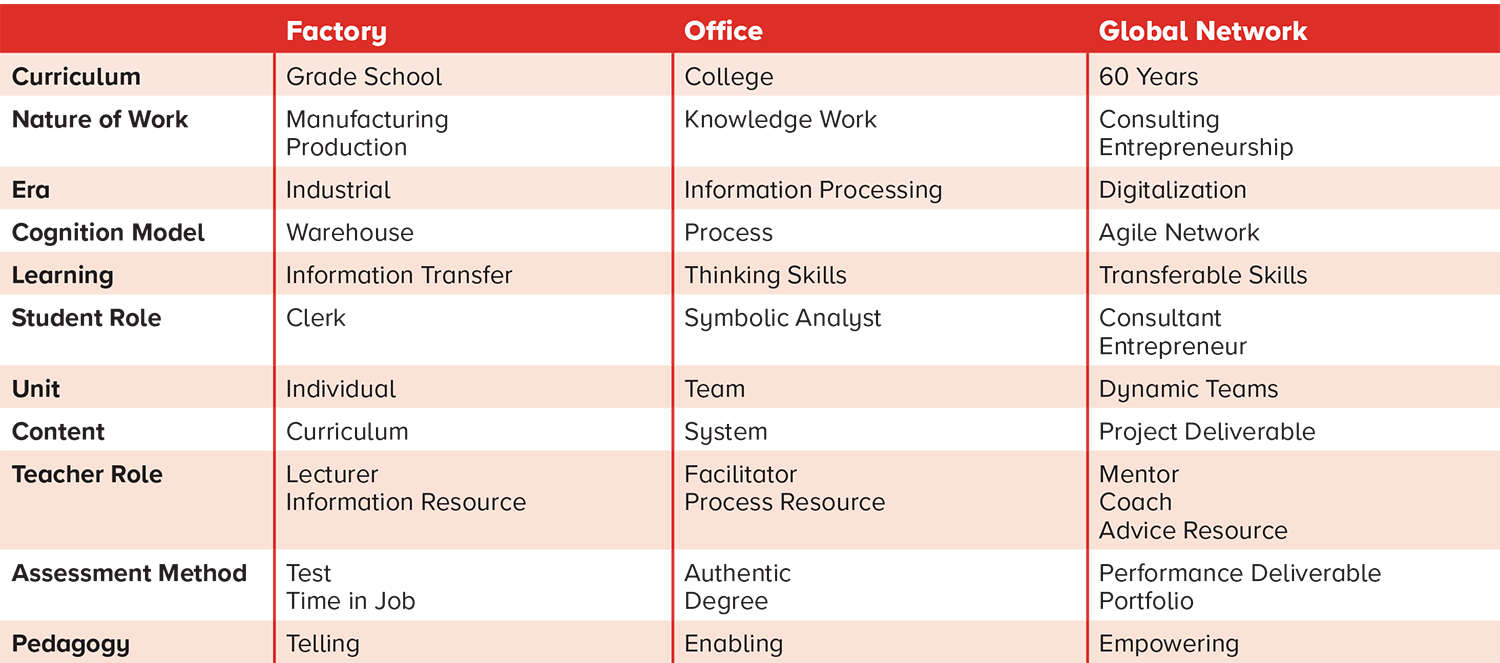

We take the term "curriculum" in the 60-Year Curriculum to refer collectively to all the elements of educational experience. It includes not only andragogy and educational content but also services that sustain instructors and learners at multiple stages of their lives and careers. A new metaphor is needed for this new learning and teaching model that serves a lifelong need. Whereas education had previously adopted factory and then office models of education, these no longer apply (if they ever did). The metaphor we propose for the 21st-century workplace of education is a "Global Network," in which participants with multiple careers and many "gigs" within each career reflect the shift from centralized to distributed organizations, from predefined to ad hoc work, and from a role-based to a consultant model of agency. The transformative changes between educational eras parallel the moves from shopping in urban centers to shopping in malls to shopping online. Workers in the Global Network era include not just musicians and startup teams but also Uber drivers, telecommuting professionals, graphic artists with multiple clients, freelance writers, authors, and copyeditors, and adjunct faculty members with a portfolio of teaching contracts.

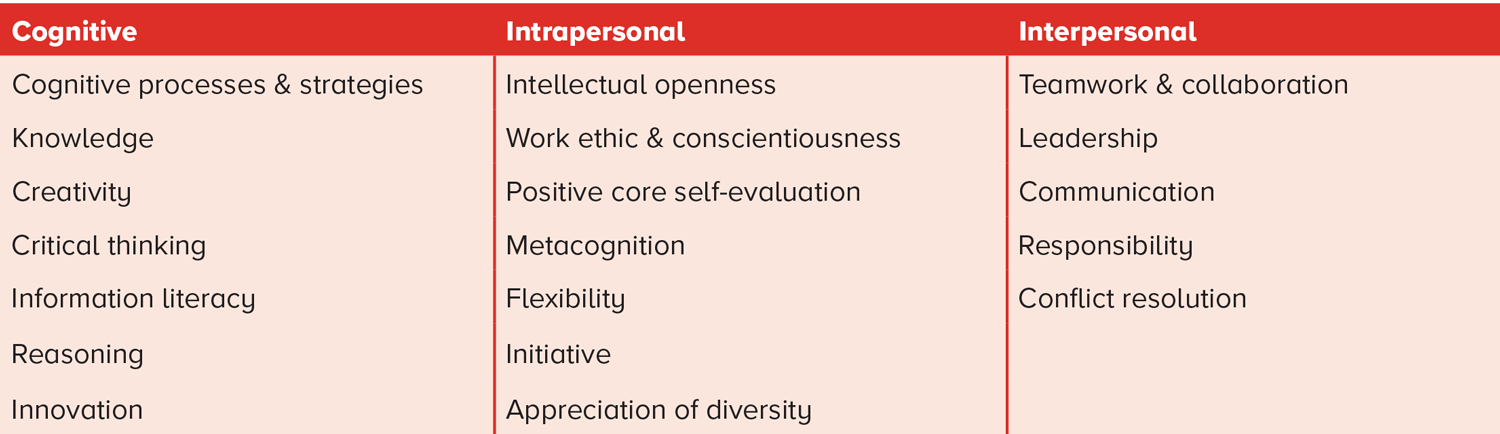

Thriving in a Global Network requires skills in three "domains of competence": cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal.8 Table 1 categorizes a broad range of knowledge and skills vital in the 21st century, grouped by these three dimensions. The knowledge and skills are variously referred to as "21st-century skills," "college and career readiness," "deeper learning," and "higher order thinking." Although there may be important differences among such categories, we refer to them simply as "21st-century skills."

Table 1. Knowledge and Skills

Students' capacity to cope with rapid, unpredictable change in the workplace and in society throughout six decades of working life depends on educators' helping them to build and exercise 21st-century skills in each domain of competency—not only during the college university experience but also in the pre-K–12 experience. Students need to develop and apply general-purpose knowledge and skills that can transfer to novel situations. But teaching how to transfer skills—how "to extend what has been learned in one context to new contexts"—is notoriously difficult.9 Transfer is "affected by the degree to which people learn with understanding."10 In other words, for transfer of cognitive skills to occur, deep learning must take place. This requires deliberate practice, an understanding of when, where, and why to use the knowledge, and an underlying motivation to apply what has been learned—all of which likely occurs in a person's first career. The extent to which this first career experience applies to career shifts is an important area for research.

The student, as a 21st-century Global Network worker, consults in a variety of roles on multiple current projects in a distributed environment. The model of the student's mind is an agile network of data and processes. Learning takes place just in time, depends on underlying transferable skills, and relies on relevant content and processing tools being readily available. The student/worker functions as an entrepreneurial consultant who works simultaneously on multiple ad hoc teams with changing collaborators.

The instructor functions as a coach, providing continuity, perspective, and methods. Performance assessment focuses on project deliverables. Preparation for a lifetime of such work requires developing the ability to learn continually and the capability to adapt to new and unpredictable situations. Consequently, education in the Global Network era requires a 60-Year Curriculum that employs an andragogy combining collaborative tactical problem solving with the strategic objective of developing transferable competencies (see table 2).

Table 2. Evolving Models of Education

We approach the methodology that is required from the perspective of learning engineering, emphasizing the applied nature of adaptive instructional methods and dynamically configurable infrastructure.11 Thus, our approach to satisfying the demand for lifelong learning is to base education on innovations in andragogy, rather than content. These new andragogies are enabled by the technologies and processes of the synergistic digital economy. There clearly could be new courses that are explicitly dedicated to novel aspects of the synergistic digital economy. However, the literacies and capacities that result from our approach do not in themselves form a new discipline or a novel curriculum. Instead, the existing curriculum of every course and program is reconfigured to reflect changes in instructional methods that establish and support habits of lifelong learning. The result is a new pattern of educational interaction, more than new substance.

The synergistic digital economy is inexorably changing what, when, and how we are learning. Online learning has removed artificial residential and temporal restrictions on courses and has matured in teaching and learning platforms that achieve immersion and enable open agency. The resulting hybrid 60-Year Curriculum makes it possible to establish and sustain six-decade-long relationships between learners and institutions.12

What is the form of these relationships? Moving existing face-to-face classes to Zoom meetings was merely a tactical response to crisis. How will courses and education itself further adapt to serve the world that students now face? How will learners and institutions evolve their relationship? Moreover, how will the higher education institution support learners to leverage, or transfer, the skills and competencies from one career to a new career? This returns us to the problems of teaching transferable cognitive skills. Transfer is successfully influenced by whether "the training introduces desirable difficulties (those that pose a manageable level of challenge to a learner, but require learners to engage at a high cognitive level)."13

Now is the time for faculty and researchers to experiment with strategic goals in the context of tactical necessities. In so doing, they must learn to leverage hybrid education and balance real and virtual experiences to engender deeper learning. That strategic objective should guide tactical responses to the present crisis and plans for emerging from it.

Conclusion

Whatever models emerge, they must include strategies that help those involved in education—both providers and students—to transformatively change their behaviors. In our opinion, the biggest barrier we face in this process of reinventing our current methods, models, and organizations for these activities is unlearning. All of us have to let go of deeply held, emotionally valued identities in service of transformational change to a different, more effective set of behaviors.14 This is both individual (an instructor transforming presentation and assimilation practices to active, collaborative learning by students) and institutional (a higher education institution transforming degrees certified by seat time and standardized tests to credentials certified by proficiency or competency-based measures).

Unlearning requires not only novel intellectual insights and approaches but also individual and collective emotional and social support for shifting our identities—not necessarily in terms of fundamental character and capabilities but, rather, in terms of how character and capabilities are expressed as our context shifts over time. We believe the success of any transformative model for education will rest on its inclusion of powerful methods for unlearning and capacity building in the people who will implement this new approach. This disruptive shift sets the stage for two dimensions of research that are critical to creating the 60-Year Curriculum. First, how do we implement a Global Network andragogical approach across the college/university? Second, how do we distribute and sustain the learning relationship between students and faculty and the higher education institution across a lifetime?

Notes

- Chris Dede and John Richards, eds., The 60-Year Curriculum: New Models for Lifelong Learning in the Digital Economy (New York: Routledge, 2020); Rovy Branon, "Learning for a Lifetime," Inside Higher Ed, November 16, 2018. ↩

- National Research Council (NRC), Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2012). ↩

- The Future of Jobs Report 2018 (Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2018). ↩

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Trends Shaping Education 2019 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2019); Southern Regional Education Board, Unprepared and Unaware: Upskilling the Workforce for a Decade of Uncertainty (Atlanta: SREB, February 2019). ↩

- Mark Muro, Robert Maxim, and Jacob Whiton, Automation and Artificial Intelligence: How Machines are Affecting People and Places (Washington, DC: Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings Institution, January 2019). ↩

- Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo, "The Wrong Kind of AI? Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Labor Demand," TNIT News (December 2018); International Labour Organization, Global Commission on the Future of Work, Work for a Brighter Future (Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2019). ↩

- Rosemary Luckin, Machine Learning and Human Intelligence: The Future of Education for the 21st Century (London: UCL IOE Press, 2018); Wayne Holmes, Maya Bialik, and Charles Fadel, Artificial Intelligence in Education: Promises and Implications for Teaching and Learning (Boston: Center for Curriculum Redesign, 2019). ↩

- NRC, Education for Life and Work. ↩

- James P. Byrnes, Cognitive Development and Learning in Instructional Contexts (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1996), p. 74. ↩

- US National Research Council (NRC), How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School, expanded edition (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2000), p. 55. ↩

- Chris Dede, John Richards, and Bror Saxberg, eds., Learning Engineering for Online Education: Theoretical Contexts and Design-Based Examples (New York: Routledge, 2019). ↩

- See Sanjay Sarma, "Rethinking Learning in the 21st Century," in ibid. ↩

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2018), p. 215. ↩

- Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey, Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock Potential in Yourself and Your Organization (Cambridge: Harvard Business Press, 2009). ↩

John Richards is Lecturer on Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Chris Dede is Timothy E. Wirth Professor in Learning Technologies, Technology, Innovation, and Education Program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

EDUCAUSE Review 55, no. 4 (2020)

© 2020 John Richards and Chris Dede. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.