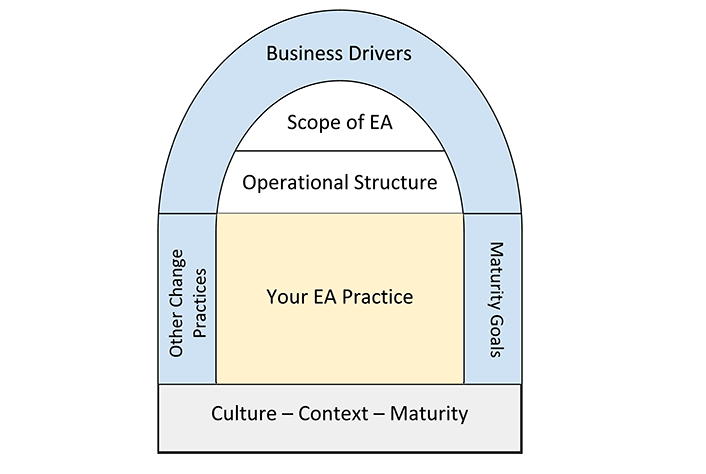

Colleges and universities that identify and understand the drivers, goals, and environmental factors of an enterprise architecture practice can create the structure needed for EA to be successful.

In 2005–06, a mid-sized private research university established an enterprise architecture (EA) practice. Officials at the institution brought in outside trainers to train a large cohort in The Open Group's Architecture Framework (TOGAF). They hired and moved staff into an EA team. They established an Architecture Review Board (ARB) and plugged it into procurement to make sure purchases met the EA standards. The ARB also reviewed projects at inception, the end of the design phase, and after the go-live to make sure that they were aligned with EA goals, were well designed, and delivered the promised architectural value.

Three years later, the whole practice was disbanded and the EA team moved into new roles. The explanatory statement from the CIO said that the university was not mature enough to support the EA function as implemented. Several years and two changes in leadership would pass before a new EA team was formed. This time, the outcome was very different. The EA practice was focused much more on strategic guidance and influence than on governing.

The Rise of EA

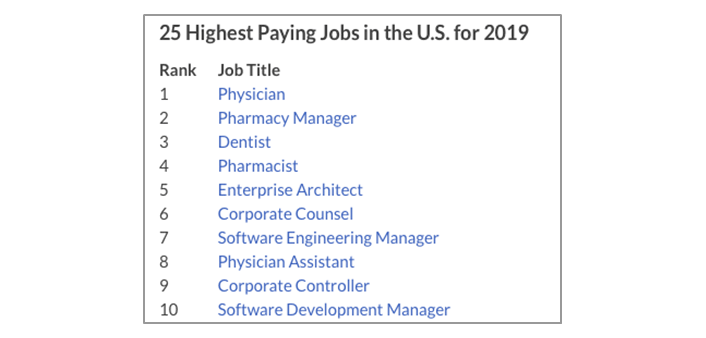

According to Glassdoor data from 2019, enterprise architect is the fifth highest-paying job in the United States (see figure 1).1 The sort of challenges that enterprise architects address—digital transformation, new competition, shifting markets, complex risk environments, the need to move to new technology platforms—are complex and reach far into the organizational structure of an enterprise. The needs that are driving EA are as diverse as the organizations that need to hire enterprise architects. This means that building an EA practice at your institution will be unique to your goals and your institution's characteristics. To design and build a good EA team and practice, you need to understand a complex set of drivers at your institution. If done well, your EA practice will help your organization adapt to the challenges and opportunities that your organization faces. If not implemented correctly, the EA team will be frustrated by lack of progress and the campus might reject the program as a whole—what I call the "institutional immune system" will reject the idea completely. And like a human immune system, it can have a lifetime memory.

Complex Business Drivers Requiring Well-Architected Solutions

The business drivers that the institution faces are the first element in designing your EA practice and hiring your first enterprise architect. Before you write a job description, you need to have a good understanding (at least in the broadest terms) of the challenges and, most importantly, the changes you need your EA practice to help you lead. You do not need to have the final design. That is up to the architect. But you need to have a sense of the direction and the future. For example, you might need to modernize teaching and learning because you know that there will be stiff competition for students in the future.

These key goals and vision help you understand what type of leadership you will need from the EA team. If your goals are around transforming teaching and learning, the EA team will need to be politically savvy and good at building commitment and trust. If the goal is around moving to the cloud, then vendor management and fiscal management might be more important.

One key is to understand where you already have deep knowledge that the EA can leverage and where the EA will need to bring the knowledge to the institution. If you have a strong compliance officer and legal team, don't hire another lawyer for your EA team. The same is true for big technical changes. Don't hire another technologist for your enterprise architect if you already have a strong technology team; instead, hire someone who can lead the organization through the changes required. Hire someone who can bring everyone together to develop a well-architected roadmap and solution.

In the many conversations I have had with EAs around the world, it is the competencies of facilitation, influence, communication, collaboration, and strategic thinking that have driven their success not technical skills. The Skills Framework for the Information Age splits these into Knowledge and Skills. You need to understand your business drivers to understand what Knowledge and Skills will be most important to your EA's success.

Culture, Context, and Maturity: Key Aspects to Designing an EA Practice

Your response to these business drivers is made more complex by the culture, context, and maturity of your organization. The drivers described above are fairly universal. I can write scenarios around business challenges such as digital transformation, risk and compliance, and technical transformation with some certainty that they will ring true with most readers.

The culture, context, and maturity parts are completely local. They relate to your institution and your institution alone. You might find peers who have similar situations, but none will be an exact match. This is key: building an EA practice will be unique to your institution because your culture, context, and maturity are unique to your campus. This uniqueness will be amplified because your goals and drivers for building an EA practice will also differ from one institution to another, and these differences will be further magnified by the maturity and adoption of other related change practices such as service management, project management, and governance.2

Culture

Peter Drucker said (or at least is attributed with saying), "Culture eats strategy for breakfast." The culture of your institution will be the greatest influence on how you structure an EA practice. Is your culture one of top-down control? Then you might have a chief enterprise architect who has veto authority over projects. Is your culture one of deep cross-organization collaborations? Then your enterprise architect should be highly visible in the organization and charged with bringing people together and building strong collaborations around your key challenges. Is your culture one of independent contributors working in silos with little or no shared controls or governance? Then architecture here will happen through personal relationships and influence.

For many institutions, the answer is all of the above. If this is the case, then you need to build a complex EA practice that includes aspects of each: top-down governance where it applies, highly visible cross-organization engagements, and deep influence and relationships in key areas. In this case, you are probably looking to build a strong federated EA practice (discussed below).

Context

Context is the regulatory and policy landscape you operate in and the external drivers that your institution faces. If your institution is highly regulated (such as a hospital or state agency), then you have some hooks to break down silos. In these instances, outside legal and policy drivers apply across the organization, and these can be leveraged to push people toward a common solution. If your institution is a wealthy private college where each department has deep pockets and few external regulations and policies drive common practices, then you will have deep challenges building an "enterprise wide" EA practice, especially if this environment is coupled with a culture of independence and distributed power. This will affect the scope of the EA practice and the type of enterprise architects you hire. In this instance, you are looking for influencers (not in the Instagram sense) who can work to build coalitions and who inspire others to a vision.

If you are in a market that is shrinking with growing budget deficits predicted for the future, that is another external driver that you can use to break down silos and force changes in the culture. As one CIO said of the financial crisis in 2009, "The culture that got us here won't get us out of this situation." Your changing context (budget cuts) can then help you drive a transition to a new culture, or at least drive changes through your existing culture. Understanding the context your EA team is working within is important to knowing how to shape an EA practice so that your architects can lead the desired changes.

Maturity

Maturity is the measure of architectural practice and thinking at your institution. Before I came to University of Washington, an Enterprise Architecture Steering Group (EASG) had built some architectural maturity. They had written EA principles and developed some EA whitepapers. This was a strong starting foundation for building an EA practice at UW.

I was at the University of Wisconsin–Madison for twelve years, starting in 2001. When I arrived, an IT architecture team was in place that was well regarded and doing good work, which established a base of maturity to build on. People were familiar with the concept of architecting a solution. They were accustomed to the fact that there is a lot more analysis than they like, a lot drawing on whiteboards and stickies before a solution is defined. That made it much easier to move up the stack and talk about enterprise architecture. The Itana EA Maturity Model (EAMM) for Higher Education features a set of defined facets of maturity for an EA practice that you can draw on as you think about your own maturity.

Do you have architects in any space that have been building maturity? If so, leverage their work to help build an understanding about what the EA practice and enterprise architect will bring to the institution. Look for stories around your institution where something was well thought out and deliberately designed by good architectural thinking—for example, "the great work the user experience architect has done for students is an example of what architectural thinking can do more broadly" is a great story to tell when you start to implement EA. These efforts are places where you can start to build a foundation for maturing an EA practice.

From those foundations, you can look at the Itana EAMM to think about what areas you want to mature first and consider target maturity levels across the various attributes. Use this to help define what you are hiring a new enterprise architect to do.

Scope of Engagement Shaping the Skills Needed

A key part of the charge for an EA team is the scope of the practice. Will your EA practice be focused on rationalizing IT services in the central IT group, or will be it focused on business transformation for the whole institution? At one Ivy League institution, the culture is one of deep decentralized independence. The goal of that institution's EA team is to build an effective and efficient set of commodity services that the independent departments can leverage. At another institution, a private Catholic university, the EA team is focused on a shift to the cloud and building out a data-driven decision-making platform for the whole of the university. At a large public university facing large ERP replacements and tight budgets, the EA team is focused on building a modern, data-rich digital platform so the university can begin to leverage machine learning and automation to manage costs.

Each of these different scopes affects the type of enterprise architect you hire, how you think of positioning that person in the organization, and what kind of EA team you need. In the Ivy League example, the institution needs a strong business relationship management function and deep influence to guide both sides (IT and departments) to the right outcome. In the private Catholic institution, the EA team has a strong governance and data-management background. At the public institution, the EA team were strong technical visionaries who could lead by example by driving pilot projects with technology teams.

Understanding the scope of the EA practice will affect whom you hire for your enterprise architect. It will also affect whom you think about connecting the architect with and where you position that role in the organization. (For more thoughts about scoping your EA team, see the Itana Scoping Your EA practice document.)

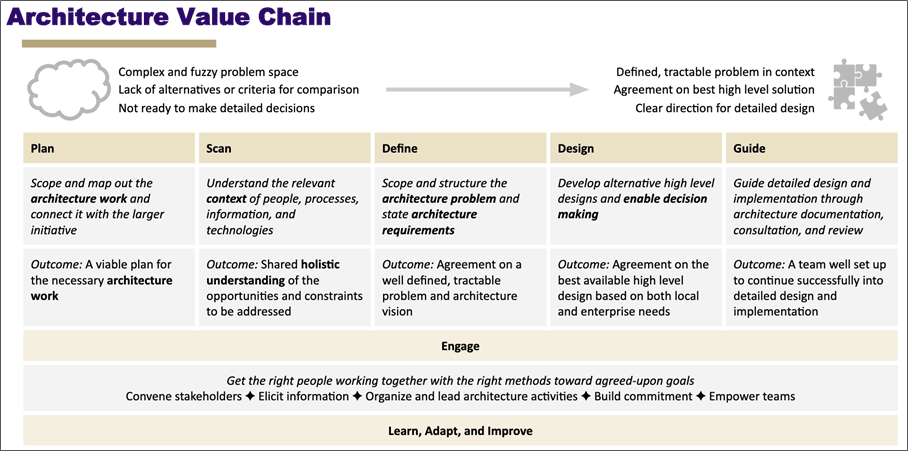

EA Practice As Value Chain

Everything mentioned above—the set of business drivers or challenges that you are facing; the culture, context, and maturity of your institution; the scope of your EA practice—all affect how you structure and staff your EA team. One way to think through this is to think about the architectural value chain and how EA on your campus would work through that value chain to deliver value. (Figure 2 shows the EA Value chain from University of Washington's EA team.)

Start with the challenges that you want your EA team to help with. Then, for each step along the way, work through the value chain, asking, "Whom would the EA team need to work with?" Ask "What support would they need and from whom?" to understand who else might need to sponsor your team. Ask "What else would they need to be successful?" to identify other key success factors such as a seat at the governance table or a deep connection to HR, finance, or the CTO.

Ask "What are the impacts of our culture, context, and maturity on the EA team's ability to execute?" Use this understanding to see where you might need to help, where there is already support, and where you might need to work on other aspects of your organization, such as governance, communications, and culture.

Finally, ask "Where do we have other change management practices (such as ITIL, project/portfolio management, change management, governance) that we can leverage to help make EA successful?"

Operational Structure: Centralized, Federated, or Feudal?

At this point, you have an understanding of the key business drivers for which you need to build an architected response. You have thought about the culture of your institution and how it will impact the EA practice. You have considered what parts of your context can be leveraged by EA to help you drive change or that will hinder you. You understand where there is any architecture maturity that you can build upon. You have defined the scope (one unit, a division, an area such as student experience) for your EA—at least to start with. You have thought through the architecture value chain and asked, in each phase, "Who would be involved, and what would make my EA successful?" You have thought about other change practices that can be leveraged or linked to your EA practice.

The next step is to think about the structure of the EA practice. Will EA be completely centralized—that is, in one unit overseeing the whole of the scope you have defined? Will EA be federated, working with local architect types and coordinating and overseeing their efforts? Or will EA be feudal, with each architecture group having its own autonomy, only coordinating with each other when they decide to on their own?

The centralized approach works best in a very top-down, command-and-control culture and institution. If everything comes through a single governance board, then a centralized EA practice can have its pulse on the whole organization. If you have only one IT organization, then EA can be centralized in that group since the IT organization will probably touch nearly all business initiatives.

If your institution has fairly distributed autonomy, then a federated model works better. In this instance, a key function of your EA practice will be to build and maintain that federation of practitioners. One way that we manage our federated practice at UW is through two communities of practice (CoP). The EA team runs a business analysis CoP and an embedded architect CoP. Each of these CoPs has about 150 members from across campus. This gives us the ability to reach out across campus to push out best practices and standards and share reference models. We draw on these CoPs to build collaborations around key architectural topics, such as a shared DevOps automation pipeline.

If you have truly autonomous functions (such as medical centers, federal research labs, or highly independent academic units), you might need to establish a set of feudal (distributed) enterprise architecture functions. You should think carefully about when and where you expect them to align. Common points for alignment are around identity and access management, integrations with core systems, data management, and key customer experience moments. Building the right governance to keep these units working in alignment is critical and difficult. The pull of the local drivers and needs will always be incredibly strong, and the act of collaborating will be seen as overhead.

Do I Need Deep Technical Knowledge in My EA Team?

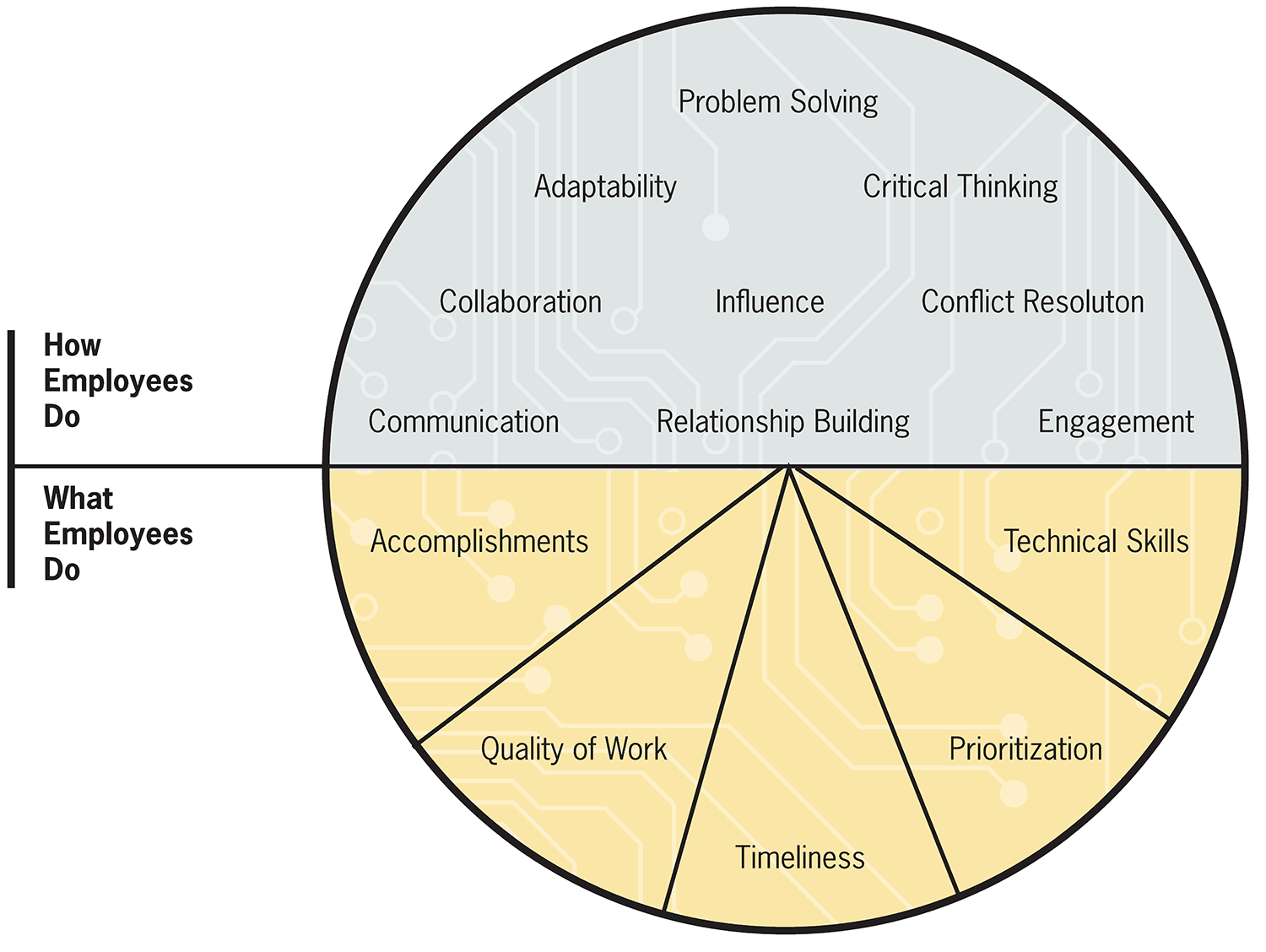

The most common misunderstanding that I encounter when I speak to groups about building an EA team is that the enterprise architect needs to have deep technical knowledge. Sometimes, in order to have the influence, you need a deeply technical EA leader. Usually, however, what you need is an effective leader with strong above-the-line competencies who can draw out the technical knowledge that is already present in the organization and who can make sense of the technical capabilities and explain them to the business partners. In a 2018 article "Scenarios, Pathways, the Future-Ready Workforce," I describe these as above-the-line and below-the-line competencies.3

A good enterprise architect needs to understand the tools and methodologies of architectural analysis. A successful enterprise architect needs to have the professional skills and behaviors (above-the-line competencies) to build strong relationships, develop influence, and facilitate difficult discussions. Chances are, your institution has a lot of technical knowledge on the IT side, or at least people who want to build that knowledge. It is up to the enterprise architect to build the multidisciplinary working groups that are needed to solve the architectural challenges. This often means getting people to collaborate with others, many of whom they have never worked with before, in completely new ways, on stuff that might seem like busy work at best to many of the participants.

Most enterprise architects I meet come from wildly different backgrounds: law, industrial design and fine arts, analytical chemistry. What they all have in common are strong above-the-line competencies in facilitation, collaboration, communication, strategic thinking, and partnership. Your enterprise architect probably doesn't need deep technical knowledge. Your enterprise architect does need to get your technologists, most of whom would much rather be alone with their monitor than in a meeting, to realize that collaboration is an important activity that delivers value to them and others.

There are, of course, places where this isn't true. There are times when you want your EA team to be piloting new technologies and bringing them into the organization. But most often, the EA team is trying to help the business partners define their goals, connect the right teams together to define good and complete requirements, and then establish good working relationships and practices so that the business goals are met.

Setting Up Your EA for Success

Several factors such as digital transformation, a complex risk landscape, increased competition, and the need to modernize technical foundations are driving the demand for EA talent. But before you hire your first enterprise architect and build an EA practice, you need to carefully think through how you will structure your new EA practice. Otherwise, your practice will run into the same problems that caused the failure of the EA practice in the story above.

Defining the challenges that you want your EA to address is the first place to start in setting up your EA practice. Take into account the culture, the context, and maturity of architecture practices at all levels of your institution. Finally, work through the value chain, asking whom the architect would need to work with and what would make that person successful (see figure 4). By doing this analysis upfront, you can hire the right person and establish the best structure and the right scope to make the enterprise architect successful. You can make sure they are plugged into the right change disciplines and governance groups.

The EA practice at each institution is unique. You need to find the right size and shape to fit your organization. In short, you need to architect your architecture practice to fit your institutional landscape.

Notes

- Amanda Stansell, "Searching for a Career Paying Top Dollar? These are the Highest Paying Jobs and Highest Paying Companies in 2019," Glassdoor Economic Research, September 18, 2019. ↩

- Debbie Carraway Piet Niederhausen, and Beth Schaefer, "Architecting the IT Organization," working group paper (Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2019). ↩

- Jim Phelps, "Scenarios, Pathways, and the Future-Ready Workforce," EDUCAUSE Review, August 27, 2018. ↩

Jim Phelps is Director of Enterprise Architecture & Strategy, University of Washington, and Founder and Chair, Itana.

© 2020 Jim Phelps. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 International License.