Thinking about the future allows us to imagine what kind of future we want to live in and how we can get there.

In 2018 we celebrated the fifty-year anniversary of the founding of the Institute for the Future (IFTF). No other futures organization has survived for this long; we've actually survived our own forecasts! In these five decades we learned a lot, and we still believe—even more strongly than before—that systematic thinking about the future is absolutely essential for helping people make better choices today, whether you are an individual or a member of an educational institution or government organization. We view short-termism as the greatest threat not only to organizations but to society as a whole.

In my twenty years at the Institute, I've developed five core principles for futures thinking:

- Forget about predictions.

- Focus on signals.

- Look back to see forward.

- Uncover patterns.

- Create a community.

#1: Forget about Predictions.

If somebody tells you they can predict the future, don't believe them. Nobody can predict large socio-technical transformations and what exactly these are going to look like. We are getting better at making point predictions. There are prediction markets and all kinds of data-rich tools with which we're trying to predict elections, market share prices, and the success of product introductions. All of these focus on one particular event, a particular point. But a lot of our work at the Institute for the Future is focused on comprehending big, complex transformations—rather than just one thing, one event. We're looking at the interconnection between technologies and society and economics and organizations.

One way to think about this is to look at the difference between waves and tides. Waves are what we see on the surface. They are fleeting events, they come and go, appear and disappear. But there is something bigger underneath that is causing these waves. Underneath the waves is the tide, causing all kinds of disturbances of which waves are just one sign. Our work involves trying to understand those tides, the deeper forces underneath the waves.

Futures Thinking Is about Readiness

So, if no one can predict the future, why think about it? Because doing so helps you to inoculate yourself. In the medical field, inoculating yourself prevents you from falling ill. In futures thinking, if you've considered a whole range of possibilities, you're kind of inoculating yourself. If one of these possibilities comes about, you're better prepared.

Futures Thinking Is about Seeing New Possibilities

Thinking about the future is also about imagining. It's about transforming how we think. It's about creating a map to the future and looking for the big areas of opportunity. We like to think about transformations, for example, in learning and work, and how they get connected and intertwined in various ways. And then we start thinking about zones of opportunity. How can we shape the future to make it more equitable? How can we amplify learning outcomes? What do we need to do to achieve these outcomes?

The future doesn't just happen to us. We have agency in imagining and creating the kind of future we want to live in, and we can take actions to get us there.

When we think about the future at the Institute, a ten-year horizon is our "sweet spot." This is for multiple reasons. Ten years is a safe place. People don't bring a lot of turf issues when thinking that far out, and they can agree on a desirable future to consider and to prepare for.

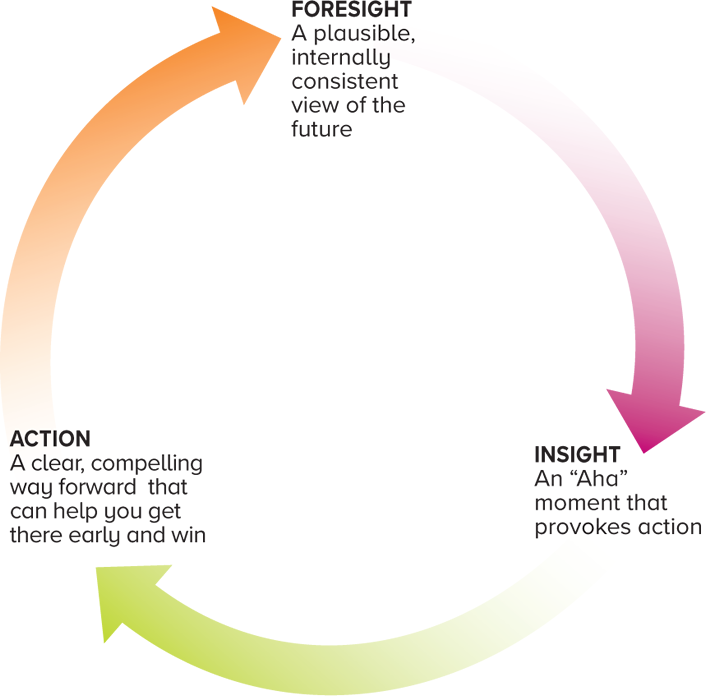

We use a cycle that we call the F-I-A process: foresight to insight to action (see figure 1). We believe that any successful strategy is based on a good insight about the future. So, as you think about the future and consider the tides—that is, as you develop foresight—ask yourself a question: What does it mean for us? What's the insight? The same foresight, the same possibility, or the same tide may offer very different insights depending on your type of industry or organization. For example, if we're moving to a new way of accreditation or credentialing, one very different from traditional degrees, the insights will likely vary depending on your institution. Ultimately the goal is to use this foresight and the resulting insight as a way to determine the action to take. Although the foresight is usually five to ten years out, the action may be needed today or six months from now. What do we need to do today or tomorrow to either prepare for that future or to shape it in a more desirable direction?

Source: Institute for the Future, 2007

#2: Focus on Signals.

What tools do we have to help us systematically think about the future and develop foresight? There is no data about the future; all the data we have is about the past. Historical data is useful when things continue as they are. You can just continue planning for the same trajectory. That's fairly easy.

The situation is different when things are changing and there are inflection points. I think we are in this space right now: notions of what learning is, how and where people learn, and the value of degrees and who grants degrees are all changing. What tools do we have to help us think about the future in this landscape? At the Institute for the Future, we use what we call signals of the future to help us develop foresight.

The science fiction writer William Gibson famously said, "The future is already here, it's just not very evenly distributed." Indeed, signals of the future are all around us today. Often these are things or developments that are on the margins. They may look weird or strange. They are the kind of things that grab your attention and make you ask: "Why is this happening? What is going on here?" A signal can be anything. It could be a technology, an application, a product/service/experience, an anecdote or personal observation, a research project or prototype, a news story, or even simply a piece of data that shows something different. Recently I read that 62 percent of jobs today do not afford people with middle-class livelihoods. For me, that was a signal. Unemployment is low, and the economy is booming. What is going on here? A signal is anything that makes you want to dig in and say: "Why? What is causing this situation?"

Let's take as examples an old signal and a new signal. In 1995, eBay first appeared on the horizon and created a lot of excitement. Strangers began to trade with each other. You trusted somebody you'd never met to sell you something, and you agreed to pay them! The significant signal here, the critical innovation of eBay, was the creation of a reputation system, for both the seller and the buyer. The creation of this online reputation system enabled strangers to conduct economic transactions easily. This idea could be carried into many different arenas, and it was. Today, all online transactions rely on some sort of a reputation system. Online reputation has become a new kind of currency. When I was a child, we were told: "Don't get into cars with strangers." Now most of us don't think twice about getting into Uber or Lyft cars with complete strangers. So, this signal, this notion of online reputation markets, changed the whole industry, allowing new kinds of transactions in which strangers come together. Just a few examples are Uber/Lyft, Upwork, LinkedIn, and the whole ecology of badges certifying that someone has certain skills or abilities.

That's the old signal. An example of a new signal is a video billboard in Sweden. It's placed at a bus stop. If somebody at the bus stop starts smoking, the billboard plays a video of a person choking. What this signal shows is that what used to be on our laptops and desktops—all of this information, all of this content—is moving into the real world. It will become available not just on billboards but all around us. We've talked about how the whole world can become infused with media, and that has happened. We can access content almost anywhere and interact with it.

If you are a futurist, you will get into the practice of looking for signals all the time. When you wake up in the morning and read the news, you will look at everything through the lens of these signals. You will naturally ask about events: "Is this a signal of something? Why?" This kind of curiosity and the ability to continually sense while also sharing with others is very important.

Ideally, people in organizations will think about signals and get together to share their observations. I call this sensing. To be a sensing organization, staff need to create some means, formal or informal, of aggregating these signals and working to interpret them. This will allow feedback and direction on what to do next.

#3: Look Back to See Forward.

I said earlier that there is no data about the future; the only data we have is about the past. While we cannot fully rely on past data to help us see the future, there are larger patterns in history that we tend to repeat over and over again. Thus, we need to look back to see forward. I've started to think of myself as a historian as much as a futurist. I'm trying to understand the larger story and to place what is happening today and what we see on the horizon into a larger context. We don't repeat our history completely, but we do repeat patterns. If we look at the invention of the printing press and the debates and worries that people had at that time, we see that those concerns are very similar to our current debates and worries about fake news, computational propaganda, bots and how they skew our public opinion.1 It's almost eerie. People were talking about fake information and propaganda and lies all those years ago!

What is the larger pattern? Changing our fundamental information, communications, and infrastructure changes our society in very dramatic ways. Why? Because of power dynamics. New media tools alter who has the voice, who has the platform, and who has the ability to shape opinion. In Gutenberg's days, the authority was with the church, which held the ultimate truth. But with the printing press, people could distribute leaflets. Luther nailed his thesis on the church doors. At that time, the transformation in the media led to social transformations, to scientific revolution, and even to wars. Eventually people created new rules, new regulations, new principles around how to value and assess this information and how to decide who has the authority to say what is true or not true. We are in the process of trying to figure this out again. This is our Gutenberg moment.

#4: Uncover Patterns.

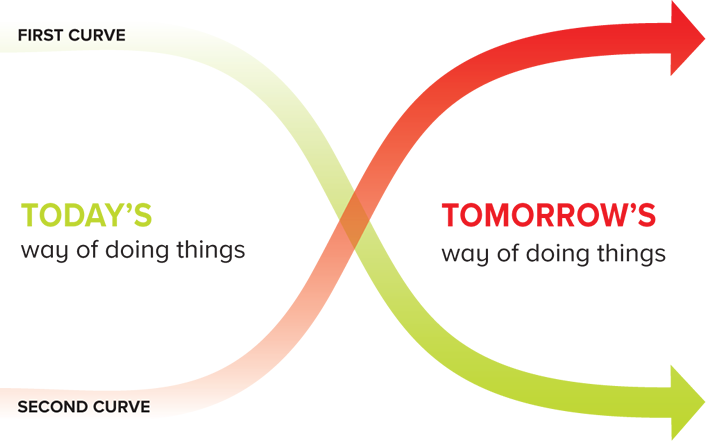

Ultimately, the goal of aggregating signals and connecting these to the larger historical context helps us understand patterns of change—the deeper tides I mentioned earlier. It helps us understand how we got to key developments shaping our future. What is the larger story? What are the tides of change? At the Institute for the Future, we've been working with a pattern that we call the Two-Curve Framework. It comes from Ian Morrison, former president of the Institute for the Future, who wrote the book The Second Curve. In the book Morrison argues that in any period of large transformation—which I think we're going through now—we are simultaneously living along two curves (see figure 2).

Source: Ian Morrison, Institute for the Future, 1996

The first curve is the descending curve. This is the curve we've lived on for a long time. We have rules, we have regulations, we have usage patterns, we know how to live this way. But that way of doing things is slowly declining, and we don't know the exact angle of the decline. At the same time, a new way of doing things is emerging: a nascent curve. We're in the early stages—we're just now seeing signals of it—but this curve tells us something about a new way of doing things.

What we see, and what I write about in my book The Nature of the Future, is that the declining curve, the curve on which we've existed for a long time, is the curve of institutional production. It is a system in which most resources—money and people—are concentrated in large formal organizations, whether corporations, news organizations, or colleges/universities. But this way of doing things is on the decline. We're moving from institutional production to what I call socialstructed creation. In this way of doing things, a platform engages large numbers of people to create something that no formal organization could, with no or very little formal structure. The best example is Wikipedia. Today, the Wikipedia Foundation has about 300 staff and contractors, but the online encyclopedia has millions of contributors and billions of users from all around the world. Together they created what no one organization could create. We're seeing this new way of doing things in open-source software, in the news media, and in other parts of our lives.

Moving from the old to the new curve requires one to behave like an immigrant. I am an immigrant to this country, and I strongly believe that we are all immigrants to the future. We are all moving somewhere new, so it is good to have the mindset of an immigrant. When you're an immigrant, you must learn a new language, a new culture, a new way of doing things. These are exactly the attitudes and skills we need to bring to thinking about and shaping our future. We must be open to learning a new language, a new culture, a new way of doing things.

#5: Create a Community.

Being a futurist or thinking about the future is not a solitary affair. I have a lot of distrust for people who say: "I'm a futurist. I went to a mountaintop, and I saw this vision, and this is your future." That's not real futurism. Thinking about the future is a collaborative and highly communal affair. It requires a diversity of views. We need to involve experts from many different domains. When we think about anything, from higher education to work, we need to include people who bring different perspectives on the topic—demographics, economics, technology, artificial intelligence, organizations. We need young people in the room. A robust forecast is a collective endeavor; it's very much a product of collective intelligence. So, if you're going to create a sensing and signaling mechanism in your organization, make sure you're not bringing in people who all think the same way. Be sure to create a diverse group of people who can contribute their varied experiences and their differing knowledge to give you much more robust views of the future.

A few years ago, the Institute for the Future brought together a group of experts and contributors to develop a forecast that ties together innovations in blockchain technologies, new patterns of working and learning, and new forms of assessment. The product of this research was a provocative video scenario titled Learning Is Earning 2026.2 What if we could bring blockchain and new reputation systems together in education? What would that scenario look like? What would it mean for students? For educators? What challenges would be created? We produced the video to raise these questions and to provoke conversations.

Conclusion

Fifty years ago, Alvin Toffler warned us of the impending "future shock," a condition not unlike the culture shock experienced by travelers to foreign countries, involving disorientation, irrationality, and malaise. "Imagine not merely an individual but an entire society, an entire generation—including its weakest, least intelligent, and most irrational members—suddenly transported into this new world. The result is mass disorientation, future shock on a grand scale."3

We seem to be living Toffler's future today. Between climate change, media disruption, and the rise of automation and machine intelligence, many people are feeling like they are victims rather than makers of the future: they are victims of the future shock. To overcome this malaise, we must answer Toffler's call to make futures thinking a way of life not just for a few innovators in Silicon Valley but for everyone—including students, educators, and average citizens.

At its best, futures thinking is not about predicting the future; rather, it is about engaging people in thinking deeply about complex issues, imagining new possibilities, connecting signals into larger patterns, connecting the past with the present and the future, and making better choices today. Futures thinking skills are essential for everyone to learn in order to better navigate their own lives and to make better decisions in the face of so many transformations in our basic technologies and organizational structures. The more you practice futures thinking, the better you get. The five principles outlined above—not focusing on predictions, uncovering signals, understanding historical trajectories, weaving together larger patterns, and bringing diverse voices into the conversation—should help you on your journey of making futures thinking a way of life for you and your community.

Notes

- Gorbis, "Our Gutenberg Moment," Stanford Social Innovation Review, March 15, 2017. ↩

- "Learning Is Earning 2026," March 6, 2016, is available on the Institute for the Future YouTube channel. ↩

- Alvin Toffler, Future Shock (New York: Random House, 1970), 12. The book grew out of an earlier article: Alvin Toffler, "The Future as a Way of Life," Horizon (Summer 1965) 7, no. 3. ↩

Institute for the Future (IFTF) is the world's leading futures organization working with businesses, governments, educational institutions, and social impact organizations to leverage its global forecasts and custom research to navigate complex change and develop world-ready strategies.

IFTF's Foresight Training program leverages over 50 years of futures content, tools, and methodologies to help individuals and organizations build foresight capacity. Our three-day introductory training in futures thinking creates new views of transformative possibilities in support of a more sustainable future.

Marina Gorbis is Executive Director of the Institute for the Future. She is the author of The Nature of the Future: Dispatches from the Socialstructed World.

© 2019 Marina Gorbis. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review 54, no. 1 (Winter 2019)