Targeted training for IT employees helps ensure that they are technically and psychologically prepared for large influxes of support and service requests. Virginia Tech's IT team used a new co-location arrangement for call center and help desk staff as an opportunity to design a joint training in preparation for fall rush.

In keeping with the rhythms of higher education's academic year, information centers may experience surges in IT support requests. To prepare employees for the significant workload increase during these surges, institutions can offer training to ensure that employees are prepared both technically and psychologically. Without such preparation, employees may be unable to provide satisfactory support to customers and may lack strategies to handle their stressful workloads.

As this article describes, with only limited preparation time, a training team at Virginia Tech collaborated with information center supervisors and employees to provide service rush training at the start of the 2017 school year. Post-rush survey results show that employees were highly satisfied with the training; the results also offer the training team clear avenues for making a strong program even better. Although their training was specific to fall rush, the team's experiences in launching and evaluating it can offer insights and lessons for other in-house information centers preparing for large influxes of service requests at any time.

Project Background

Virginia Tech is a public land grant university established in 1872. Each August, more than 34,000 students—including 6,800 new students—begin the school year. At that time, service requests to Virginia Tech's Division of Information Technology (DoIT) information center, known as 4Help, increase at a rate of two to three times that of other months. The requests peak during fall rush—the 12 days that begin on moving-in day and conclude at the end of the first week of classes.

4Help is led by an associate director and consists of a call center and help desk. In July 2017, two supervisors led the call center's eleven full-time employees, or agents, while another supervisor led the help desk's nineteen undergraduate student interns, or consultants. Here, I refer to the supervisors and the associate director collectively as the supervisors.

For the past several years, the call center and help desk operated rather independently:

- Call center agents primarily handled Tier 1 support: incoming phone calls for support that typically could be addressed immediately, without much investigation.

- Help desk consultants handled Tier 2 support: support requests that came in through an IT service management platform and typically required investigation.

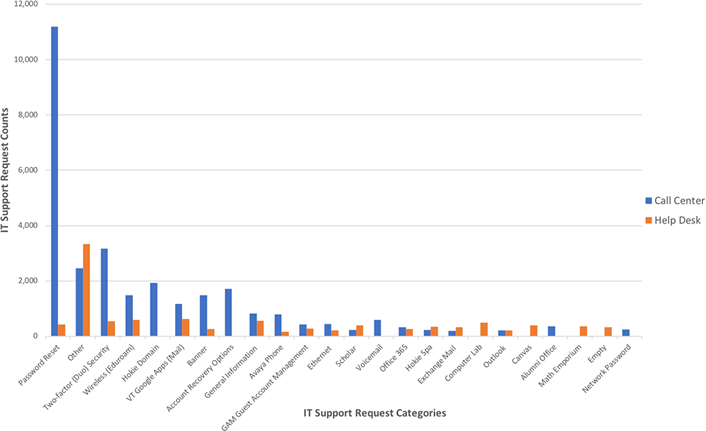

Although the functions were neatly divided, the same was not true of the actual service requests. For example, as figure 1 shows, the second biggest category of support requests was Other—that is, ill-defined requests that did not fit into a common support category and required investigation. Further, when a request requiring investigation came in via phone, it was passed from Tier 1 to Tier 2, but support requests were seldom passed from Tier 2 to Tier 1.

While both groups can handle certain common service requests, the groups were neither cross-trained nor co-located, which exacerbated the challenge of quickly managing service calls, particularly when they came en masse, such as at the start of the academic year.

To address this, in early July 2017, we moved the help desk group and call center into a single office. With fall rush fast approaching, the 4Help supervisors had a lot on their minds. Should we combine and improve the training we offer to prepare 4Help employees for the fall rush? Why or why not? If we should, what training should we offer and how should we offer it? With just a month left, what strategies should we use to prepare for the training and thus achieve the best outcome?

Is Training for a Service Rush Needed?

Virginia Tech has a small training team that works closely with information center supervisors to train the center's employees. We had previously offered fall rush training consisting of separate training for agents and student consultants. However, with the two groups co-locating in one office, and with our future cross-training needs in mind, we decided to reexamine our previous effort to see if we needed a new, combined training for service rush.

To determine this, we first conducted an analysis to see if there was a gap between the expected knowledge and skills and employees' existing knowledge and skills. Ideally, we wanted our employees to be both technically and psychologically prepared for a service rush.

Technical Preparedness

To perform their jobs effectively, 4Help employees must have adequate technical knowledge and skills. Earlier in the year, the training team worked with 4Help supervisors to identify necessary training topics and how often they should be refreshed during a year. Among the twenty-four identified topics, some cover support items that are frequently requested across the year, while others cover requests that either fluctuate greatly depending on the time of year or are only occasionally needed but still integral to optimal operation. For example, support on password reset is among the highest requested items across the year, including during fall rush. In contrast, support needs related to connecting personal devices (such as Kindle e-readers, game consoles, or TV boxes) to the campus wireless network are less common and concentrated at the start of a new school year when freshmen move in to on-campus dorms.

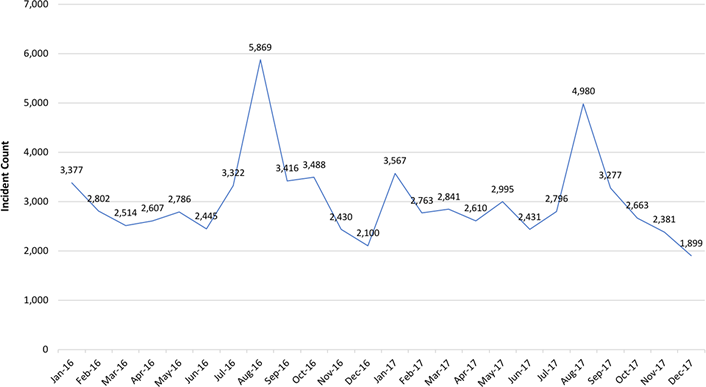

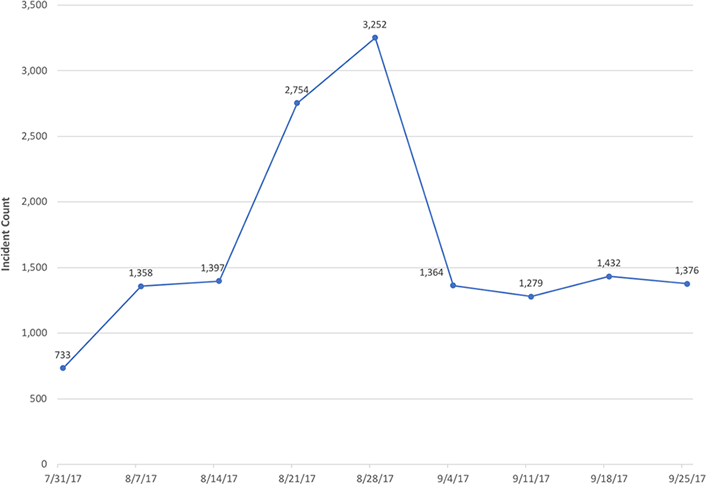

Figure 2 shows the surge in support requests during fall rush in August 2016 and 2017, while figure 3 shows a weekly request breakdown for August and September 2017. To handle the high demand during the two-week fall rush period, 4Help employees must be competent in various support topics. In our case, with only a month left, it was not possible to provide training on all twenty-four topics. We therefore decided to identify the support types frequently requested during fall rush and focus our training accordingly. Doing so would allow us to use our time wisely and achieve better efficiency. Based on experience with fall rush in previous years, we identified six technical topics that cover high-demand support requests during fall rush: password reset; wireless set-up for devices, printers, and guest accounts; wireless connection (Euoroam); two-factor authentication; and Office 365.

Psychological Preparedness

By helping our employees be technically prepared, the training increases their confidence in handling requests. This is especially true for frequently requested topics during a service rush. In addition to technical topics, our fall rush training included customer service. We created a new online training module on phone and email etiquette and released it two weeks before fall rush to help our 4Help employees increase their customer service skills. Topics included the basics of effective communication using phone and email, strategies to de-escalate interactions with angry customers, how to stay focused throughout the day, and other topics that help employees manage heavy workload and stress.

Given this module's length, we offered it prior to (rather than as part of) the face-to-face training. We also integrated a "Fish! Philosophy" session, based on the Seattle Pike Place Fish Market's customer service model, into our face-to-face training to emphasize the importance of great customer service, teamwork, energy, and results. Together, these soft-skills training sessions helped psychologically prepare our 4Help employees for the fall rush.

The Gap

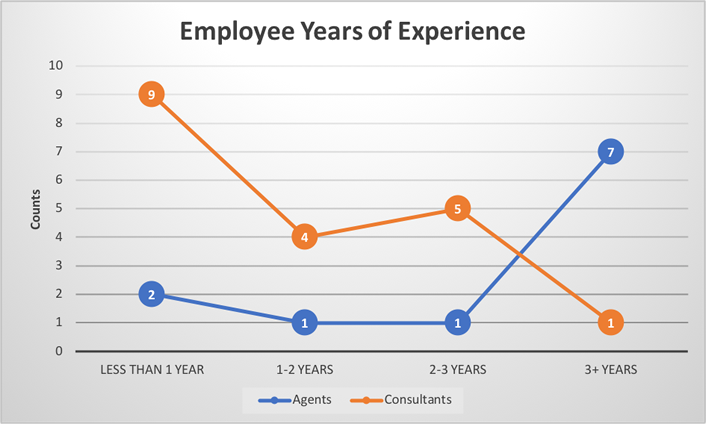

As figure 4 shows, our 4Help employees vary in their IT support experience. When we began planning our new training program, two of our eleven full-time agents had been with 4Help for only three months and had not yet been fully trained on all twenty-four support topics—including some of the topics identified for fall rush. Of the nineteen student consultants, nine had joined two months before to help with student orientation and had not yet received any technical training to transition to the consultant role.

Although we did not expect our new employees to be able to help customers with advanced topics, we did need them to answer phone calls, input support tickets, and conduct other basic tasks so that more-experienced employees could concentrate on advanced support requests. Our preliminary analysis therefore indicated that the new employees definitely needed the fall rush training.

While it was easy to determine new employees' training needs, it was less clear whether our relatively experienced employees would need fall rush training. Ideally, we'd have an inventory of each employees' competency level on all support topics to help us make a data-driven decision. Because we did not have that information, however, we had to rely on the supervisors' evaluations of each employee's competency.

According to the 4Help supervisors, even though some employees had been with 4Help for years, they could not handle certain requests independently due to forgetfulness related to the time lapse between these less-common requests. This gap between the expected knowledge and skills and existing knowledge and skills led us to determine that even our experienced employees would benefit from revisiting the fall rush training topics. We also realized that it would be beneficial to have experienced employees in the same training as new employees because they could supply important tips and tricks based on their experiences.

Training Design and Development

With just a month before fall rush, our training team, including the 4Help supervisors, had to determine the training format, schedule, and location; training topics and their length; attendees and presenters; and other training options.

We used two strategies to prepare for fall rush training. First, we used the existing fall rush training as a foundation, examining what it consisted of, as well as what worked and what didn't, and identifying improvements to it to provide a better training experience and achieve better training outcomes. Second, given the numerous and varied tasks involved, a collaborative approach was essential to tap into the experience and expertise of each team member.

Improving on Previous Experiences

In the past, we had offered separate fall rush trainings for agents and consultants. The full-time agents attended a full-day training camp covering service topics specific to call-related requests. In contrast, student consultants attended a two-hour in-person training session focused on topics specific to help desk. Consultants were also required to complete complementary online training on particular topics. Once the two groups moved to the same location, the need emerged to train all employees in both call-related and help-desk-related topics. Therefore, rather than providing separate training for the two groups, we decided to provide the same training for everyone so that they would be exposed to all support topics related to fall rush, rather than only topics specific to their group.

To improve on the previous training experiences, we had to examine previous fall rush experiences, including what had been successful and what could be improved. Given our time limits, it was essential to establish priorities; to choose them and our areas of improvement, we used three criteria:

- areas with obvious weaknesses;

- areas that, if enhanced, could dramatically improve overall training effectiveness; and

- weaknesses that could be addressed within the one-month timeline.

Given these criteria, we chose the following key improvements:

- create a course portal to organize and archive training materials;

- develop a module to enhance presenters' skills in training delivery; and

- redesign some training materials to achieve optimal training outcomes.

The training course portal. In the past, we made fall rush training materials available to employees, but it was up to them to organize the materials, which came from different presenters and were accessible via different media. For example, some files were sent to employees via email, while others were available through shared cloud services, such as Google Drive. Consequently, retrieving needed materials required effort. Further, once a presenter left the unit or the university, access to his or her cloud-based materials was lost.

To optimize the access and retrieval process, we created a new training course site in a learning management system to store and organize training materials. Each training session was organized as a module with relevant training materials; this offered both long-term access and easy retrieval. The training course site serves as a central location for training materials and includes the training schedule and other relevant information.

Support for presenters. To best utilize the talents of our employees—especially those who have been with 4Help for years and have extensive experience in various support topics—we recruited some of them as presenters. Many of them, however, had little if any experience as trainers. To help them deliver effective training sessions, we created a train-the-trainer module for the new course site. Unlike other modules, this module was not published; it was available only to course instructors.

As with the overall training design, we did not start from scratch when creating this module. Instead, we used videos on how to become an effective trainer from Lynda.com, selecting thirteen videos on topics such as adult learning principles, preparing for training, effective training techniques, and managing and engaging participants. For each video, we created two to five questions to help focus the presenters on key concepts and ideas. At the end of the module, presenters can take a quiz to check their understanding. Given our time constraints, we made this module optional to all presenters, but we encouraged them to review it and complete the quiz to the best of their ability.

Using employees as presenters has several benefits. First, because employees deal with support requests on a daily basis, they often have the best knowledge of the subject matter. As presenters, they can share this accumulated experience with peers, helping them avoid costly and time-consuming trial and error. Second, getting employees involved in training delivery is a way to recognize their expertise and strengths. It also gives them opportunities to develop and practice skills outside their regular duties. Third, it helps lighten the training team's workload. Unless these employee trainers are sufficiently supported, however, training results may be suboptimal due to the new trainers' inexperience. It is therefore imperative to give them information on effective training design and delivery so that they can succeed as trainers and help employees better learn.

In addition to the train-the-trainer online module, we also paired each employee presenter with a training team member to identify and update existing training materials, develop new training materials, and design training activities and flow. The training team also consulted with employee presenters on overall training design, with a focus on integrating engaging activities into the training sessions.

Course material redesign. A quick review of the presenters' training materials indicated that some required improvement to achieve ideal training outcomes; in particular, many were only text-based. As studies indicate,1 the proper use of instructional graphics can lead to better information processing, retrieval, and application. For example, during fall rush, various IT support services were available across campus to help students (especially freshmen) start the new school year. Instead of simply using texts to present the information, we redesigned messages as visual representations.

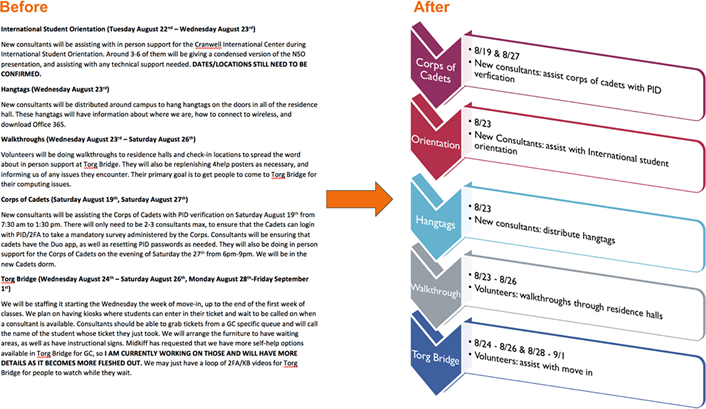

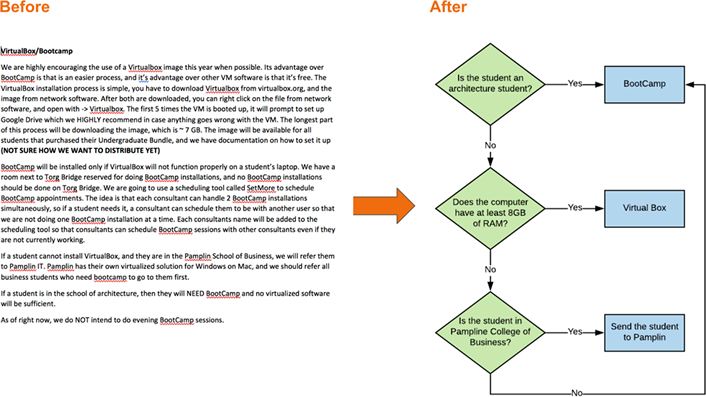

Figure 5 shows an example: In our redesign, we sequenced events chronologically and included only essential information, which is much easier to read and process than using text alone. As another example, students had to install different virtual machines depending on their college affiliation and/or computer memory. Using text alone made it difficult for them to quickly determine which software they needed. As figure 6 shows, the redesigned decision chart helped both students and the IT support staff determine which software to install.

As in any type of intensive training, we presented a wealth of information to employees in a short time period. To ensure better information processing and future retrieval, our trainers examined their training materials with critical eyes to determine how best to present information to make it easy for learners to process and retrieve.

The Collaborative Approach

Collaboration is often used when a complex task or project requires a broad spectrum of skills from across different units to achieve optimal organizational results. Developing and delivering training is just such a task: It requires different skill sets, including both subject-matter knowledge and the ability to design and develop effective training.

In our case, 4Help supervisors are familiar with IT support topics, customer needs, fall rush requirements, individual employees' knowledge of different support topics, and many other aspects of 4Help's daily operations. However, the supervisors may or may not have experience in systematic training design and delivery. In contrast, the training team has both skills in training design and knowledge of information center operations. Due to frequent technological or procedural updates, however, training team members' knowledge of support topics and details had fallen behind.

Collaboration is also useful in tight time frames when more than one individual or unit is needed to finish a project on schedule. So, given the needed skill sets, the time constraints, and our workload, we realized that it was essential that the two groups collaborate on planning and developing the fall rush training.

Once we reached the decision to collaborate, we had to determine how to implement the collaboration. To do this, we quickly analyzed each team member's skill set and the requirements of different tasks, and distributed work among the team members accordingly. The training team was in charge of the overall planning, with considerable input from the 4Help supervisors. The training team was also responsible for creating the train-the-trainer module, redesigning some training materials with visual improvements, and building a training portal within the university's learning management system. The team also collaborated with some of our presenters to design training activities and consult on effective training delivery.

The 4Help supervisors identified the employee presenters and an external presenter. They also booked the training classroom and arranged work schedules so that all employees could participate in the training, including those working evenings or the night shift. Finally, both the training team and the supervisors worked with presenters to ensure that training materials were up to date and complete before the deadlines and that the presenters were ready to deliver the trainings.

Training Delivery and Evaluation

We conducted the training just prior to the start of fall rush.

Training Logistics

Because 4Help offers 24/7 IT service to the university, it had to operate as usual during the fall rush training. We therefore divided the employees into two groups (each with both agents and consultants) so that one group could train while the other ensured regular 4Help operations for both calls and the IT support portal.

Both groups received the same training, with each group participating in two half-day training sessions on two consecutive mornings or afternoons. The training course portal was open two days before the training to allow employees to access the schedule and materials.

Evaluation

We received positive feedback on the training in both formal and informal ways. Immediately following the training, some employees came up to us and thanked us for offering such an organized and useful workshop. To collect more formal feedback from all participants, we conducted a brief survey after fall rush had concluded.

We based this survey timing on two considerations:

- Because the training completed as fall rush was starting, all 4Help employees were busy; having to take a survey during fall rush would have added an additional burden.

- The training's usefulness could best be determined after employees—many of whom were new to 4Help and fall rush—had experienced the event and applied what they had learned.

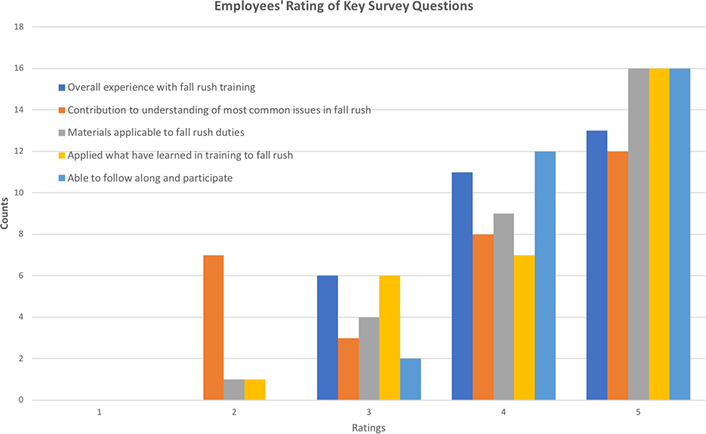

The survey questions included both multiple-choice and open-ended questions. The multiple-choice questions asked employees to rate items on a Likert scale of 1–5, with 1 representing the lowest rating and 5 representing the highest. As figure 7 shows, questions included those on the overall experience of fall rush training, the training's usefulness, how employees applied the training to fall rush, the training's pace, and each topic's value.

All thirty employees completed the survey. Among them, twenty-four rated their overall experience with fall rush training as very good or excellent. On the question of how the training contributed to their understanding of common fall rush issues, twenty rated it as very good or excellent. Additionally, twenty-five agreed or strongly agreed that the material covered applied to their duties during fall rush, and twenty-three reported that they applied what they have learned in the training to their work during fall rush. On the question of how well they were able to follow along with the presenter and participate in the training, twenty-eight agreed or strongly agreed. We also asked participants to rate how valuable each of the nine training topics was to their work. At least half of the employees rated all topics as quite valuable or very valuable; the most valuable topic—Office 365—was rated as quite valuable or most valuable by twenty-four of the thirty employees.

The survey included four open-ended questions to collect qualitative data on what employees found most and least valuable about the training, which topic we should include in future trainings, and any other comments they had.

Regarding the training's most valuable aspect, twenty-nine employees provided feedback. Although the question did not ask for comments on specific training topics, seventeen people mentioned specific topic sessions as valuable. The remaining comments covered the overall training's usefulness, the interaction and hands-on experience, and the training course portal.

Regarding the training's least-valuable aspect, twenty-five employees provided feedback; again, while the question did not specifically ask for comments on the topics, eleven named particular sessions that they found least valuable. In comparison to the most valuable aspect question, answers to this question focused on only a few topics, which indicated that the employees thought most of the topics were valuable. In addition, nine employees indicted that they found all topics valuable.

Regarding additional topics for future fall rush training, twenty-four employees responded. Of those respondents, nine could not think of any needed additions; the majority of the remaining responses asked for additional coverage on existing topics. We also received four requests for topics not covered in this training: two on email settings and troubleshooting, one on computer diagnosis, and one on phone use.

Finally, in terms of any additional feedback on fall rush training, twenty-four employees responded. Of those, nine said they had no additional comments, while five used the space to praise the training. One employee thought using employees as presenters was effective, while another requested more input from experienced employees in terms of tips and tricks for different tasks. Several employees pointed out that two of the sessions had repetitive content; this was the result of a lack of coordination between the two sessions (one was from our internal presenter and the other from an external presenter).

Future Improvements

Continual improvement is integral to any IT service. Indeed, many in IT follow the cycle of continual improvement, which consists of four steps: plan, do, check, and act, or PDCA.2 As part of the "check" step, we plan to improve several aspects of future fall rush training based on feedback from the training participants, our observation, and reflection.

Longer Training Periods

First, all previous fall rush trainings used an intensive workshop format, covering most training topics within one or two days. While this approach helped employees quickly review IT support topics, it did not support the best learning outcome. Research shows that spreading out learning and assessments over a long time period is much more effective than intensive learning in a short time frame.3 While these findings focus on formal education, research in faculty development also shows that learning sustained over time and with more total hours is more effective than one-time or brief offerings, both in terms of faculty learning and in helping faculty change their classroom teaching behavior.4 Therefore, in the future, we plan to start the fall rush training early and spread it over weeks or months to achieve better training results—and, ultimately, better job performance.

A longer training period has yet another benefit: It gives employees time to practice what they have learned in their daily work. In comparison to our intensive training right before fall rush, which required instant performance following the training, this method offers employees time to internalize knowledge, translate it into practice, and make necessary adjustments.

Data-Driven Training Decisions

Second, we plan to use data to help us improve our training decisions. Data-driven decision-making is important in that data can help us evaluate the reliability of our intuition and assumptions. Today, data on IT support is becoming increasingly easy to collect, especially using IT service management systems such as ours, which collects and manages data from various resources and makes them available through a centralized system. Such easy access, however, requires intentional consideration if we are to use data to achieve ideal business results.

For example, to select the fall rush training topics from the twenty-four existing topics, we solicited inputs from both the 4Help supervisors and the training team. These inputs were anecdotal, based on individual experiences rather than 4Help's operational data. Even though decisions made this way can be good enough in themselves, validating decisions using operational data can make the decisions more robust. For our next offering, we plan to examine the most requested support items from the previous fall rush to support sound decision-making.

Required Trainer Training

Third, although we created the train-the-trainer module, presenters were not required to review it due to the time constraints. Because many of our presenters were not trained to design and deliver training, some based their sessions on what they had experienced as a student or a trainee: lengthy lectures. However, for training to be effective—especially when it is intensive and compressed into a brief time period—it must engage participants and avoid the cognitive fatigue that occurs when they are bombarded with hard facts and boring presentations.

To support effective training, our train-the-trainer module includes information on powerful training strategies, including how to engage participants in interactive activities. In the future, we will make this module mandatory for all presenters. By helping presenters apply effective training strategies in their sessions, we hope to improve the overall quality of the fall rush training.

Planning, Preparation Are Key

Our experiences and our employee feedback show the benefits of providing employees with training and preparing them in advance, technically and psychologically, for the busiest times of year. To achieve optimal training results, I suggest you start early to allow plenty of time for adequate planning and preparation. However, even in brief time frames, you can still provide a quality training through good planning, which involves assessing the training needs, determining the training topics, improving on previous experiences, and taking advantage of team collaborations.

Each higher education institution has a unique context and structure and particular needs, but some of the ideas shared here can be useful in planning a similar service rush training for in-house information centers that provide IT support.

Acknowledgment

A special thanks to Lucas Sullivan, Teresa Snavely, Jennifer Gay, Leonard Comaratta, Michael Hodge, Ryan Gorkhalee, and our intern Abidi Jima for their great support and collaboration in the fall rush training project.

Notes

- Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger, III, and Mark A. McDaniel, Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014); and Ruth Colvin Clark and Chopeta Lyons, Graphics for Learning: Proven Guidelines for Planning, Designing, and Evaluating Visuals in Training Materials (San Francisco, CA: Pfeffer, 2011). ↩

- Corinne Johnson, "The Benefits of PDCA," Quality Progress 35, no. 5 (2002): 120. ↩

- Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel, Make It Stick. ↩

- Michael Garet, Andrew C. Porter, Laura Desimone, Beatrice Briman, and Kwang Suk Yoon, "What Makes Professional Development Effective? Results from a National Sample of Teachers," American Educational Research Journal 38, no. 4 (2001): 915-945; and Susan Loucks-Horsley, Katherine E. Stiles, Susan Mundry, Nancy Love, and Peter Hewson, Designing Professional Development for Teachers of Science and Mathematics, 3rd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2010). ↩

Deyu Hu is Associate Director of Training, Research, and Special Initiatives for IT Experience and Engagement in the Division of Information Technology at Virginia Tech.

© 2018 Deyu Hu. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0 International License.