Far from replacing instructors, adaptive learning gives them the data they need to engage students in new ways.

Proponents of adaptive learning (AL) technology tout its great value as being its ability to create student-centered classrooms in their most individualized form, shy of limiting the student-to-teacher ratio to 5:1 or less. AL does this by customizing learning based on the knowledge each student brings to the course. While this personalization benefit is certainly seductive, the major question some educators are left with is: Where does this leave the teachers?

Sherry Turkle, a clinical psychologist and founding director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self [https://ilp.mit.edu/node/37106], claims that online classrooms limit engagement between students and instructors, and she questions the ability of online education to meet student needs over the long term. Ultimately, she argues, online education has made "the value of teachers … ever more clear" by underscoring students' desire for connection with them.1

Although Turkle believes that student–teacher relationships can truly thrive only in a face-to-face setting, we have found that AL-augmented classrooms provide a unique gateway to a personalized, individualized, instructor-driven online classroom. However, AL-augmented classrooms cannot simply be instructor facilitated, relying on technology alone to create a personalized experience; instructors must enhance the personalization offered by the AL technology by implementing strategic, targeted instructional approaches.

Although it can be used in traditional classrooms, AL has been a growing area of interest for online courses. In online classrooms, AL technology is often directly embedded and gives students a visual representation of their progress and improvement as they work through lessons and improve their mastery of a topic. AL technology for online courses is a relatively new phenomenon; in 2012, our institution, Colorado Technical University (CTU), became an early adopter for online courses. That same year, Tyton Partners described this type of AL usage as a "nascent market spring-loaded with potential."2 By 2015, Tyton was describing AL as an important field in educational technology.

Still, AL has faced resistance, especially from teachers and instructors expected to adopt the technology in their classrooms. As George Lorenzo noted in his EdSurge article "Failing Forward with Adaptive Learning in Higher Ed," much of the concern surrounds the lack of sound research and proven techniques related to instruction and AL technology. Given this, integrating AL into classrooms has thus far been largely trial-and-error — a common scenario among early adopters of any technology. Nonetheless, we can already see AL's potential: According to a 2016 article in BizEd, "seventy-five percent of students using adaptive learning technology report that it is very or extremely helpful in allowing them to retain new concepts; and 68 percent report that it makes them more aware of previously unfamiliar concepts."3

To help push AL technology beyond the promise noted in these early years, it's time to take stock of what we have learned thus far and use those lessons to begin assembling a foundational instructional philosophy for working with AL technology.

Adaptive Learning: How Does It Start — and Is It Enough?

As an early adopter of AL technology, CTU recognized both the potential and the advantages of personalized learning content. We therefore committed to developing an adaptive teaching and learning strategy as part of CTU's long-range academic programming plan.

We began piloting our intellipath AL platform in math and English courses in 2012. The initial pilot's scope consisted of three courses with a total of 431 students over two sessions. In the first year, the pilot expanded beyond general education courses in science and math to business courses in accounting and statistics. Within three years of piloting, CTU had launched 63 AL-augmented courses with more than 32,000 users.

Starting small and creating a controlled expansion was intentional and aimed at ensuring that the process included evaluation and assessment. In a 2016 EDUCAUSE Review article, "Adaptive Learning Platforms: Creating a Path for Success," CTU Chief Academic Officer and Provost Constance Johnson noted that by "analyzing the platform at targeted intervals throughout its development and initial rollout, we were able to make critical adjustments before extending the platform to larger audiences."4

Since the initial pilot, CTU has effectively scaled the AL adoption process across the university, with the expansion largely driven by academic program needs, faculty feedback, and students. As of today, we have expanded AL to 170 different courses and more than 98,000 students. As we move forward, continuous improvement remains essential; as Johnson put it, "Since adaptive learning is integrated into the university's culture, we continue to explore new ways to use the technology to make experiences better for all stakeholders in our community — students, faculty, support staff, and administrators."5

As we move beyond implementation, we are also further exploring the most effective ways to integrate AL, including using strategic, targeted instructional approaches to create an AL classroom that is not only instructor facilitated but also instructor enhanced.

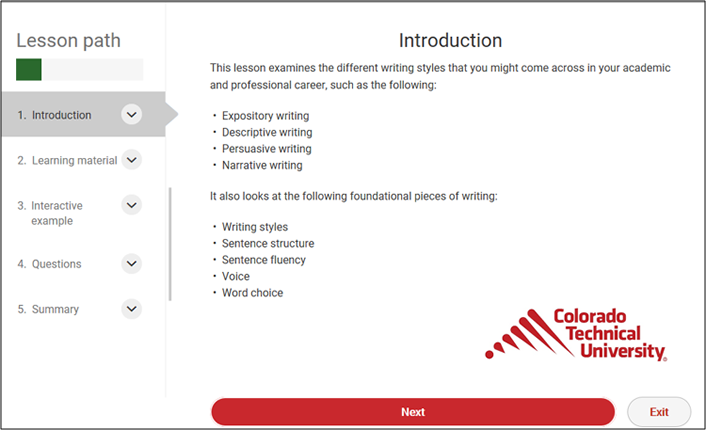

AL at CTU: AL-Enriched and All-Adaptive

At CTU, we embed AL technology into the learning management system. Each AL assignment is tied to a specific unit and extends throughout the week. The unit consists of various lessons related to that topic. Prior to starting the lessons, students complete a series of questions to assess their knowledge of the content for that entire unit. This assessment helps customize each student's learning map, so all students know which lessons to focus on first. Throughout the week, students work through all of the lessons to reach 100 percent progress; they then work to increase their mastery in any lessons where improvement is needed. As figure 1 shows, each lesson includes an introduction, learning material, interactive examples, questions, and a summary. The lesson questions allow the student to demonstrate mastery of the material.

CTU classes run either 5.5 or 11 weeks. While not all classes use AL, it is included in various online and blended campus courses. CTU does not use a prescribed format to incorporate AL components, but our AL-augmented courses use one of two basic designs: the AL-enriched classroom and the all-adaptive classroom.

The AL-enriched classroom is the more common classroom design. Within that structure, the assignment breakdown varies from including adaptive assignments in as few as two units to having them in every unit. In AL-enriched classroom, students also must complete multiple non-AL assignments, such as in-class assignments, online discussion boards, individual projects, or group projects, depending on the course and modality.

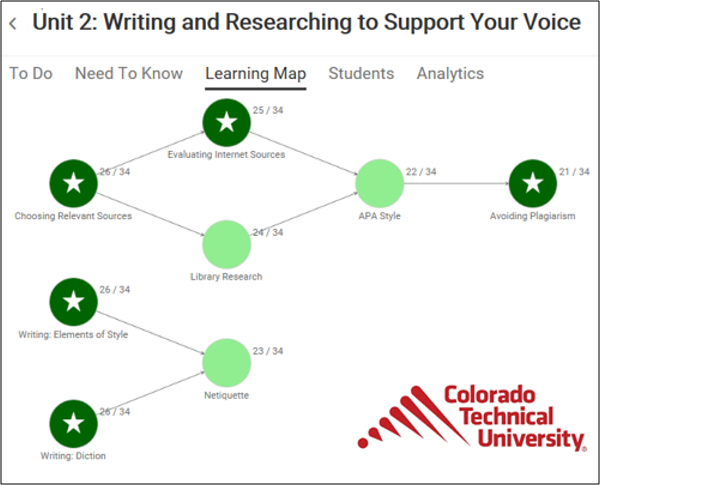

Professional Written Communications, the second course in CTU's writing sequence, is a good example of an AL-enriched course. In this 5.5-week course, students have an AL assignment in four out of the five units. Students participate in a discussion board in four units and submit an essay in two units. The course's adaptive content is foundational and designed to prepare students for the written components. For example, as figure 2 shows, students use a learning map in Unit 2 to prepare for their research projects.

In contrast, students in the all-adaptive classroom have adaptive assignments in all units, along with an introduction discussion board worth less than 1 percent of their overall grade and perhaps one other non-AL assignment during the term. In these courses, interaction outside the AL environment is limited but still exists through synchronous chats, classroom announcements, outreach, and so on.

Academic and Career Success, the first course most CTU students take, is a good example of an all-AL classroom. In this course, students complete a short introduction discussion in Unit 1 and then a more detailed discussion in Unit 3. The rest of the work is completed through AL technology. Students have approximately eight lessons assigned in each unit, all targeted at preparing them to demonstrate mastery of the course objectives.

The Instructor's Role in Adaptive Learning

AL technology lets instructors and students work closely together to ensure that knowledge transfer is taking place. Through AL technology, instructors have access to their students' real-time data and analytics, including student mastery and progress, rate of progress, performance, and engagement.

Although the AL platform is the same, the two types of AL-augmented classroom structures at CTU call for slightly different instructional approaches — and thus a different set of faculty expectations for each. For AL-enriched classrooms, expectations emphasize monitoring students' learning maps and replying to questions and messages within 24–48 hours. Instructors are also expected to have individualized and targeted engagement with students about their progress and to regularly transfer score updates from the AL platform into the classroom gradebook.

For all-AL classrooms, faculty engagement in the platform becomes even more critical through increased regular contact that demonstrates sustained, targeted, and individualized instruction. For example, instructors should be interfacing with students via the AL technology several days a week by examining course-level data — such as performance on individual lessons and time spent on lessons — and determining where students need additional support. That support might occur by providing supplementary materials, offering advice on next steps, or by reaching out to offer individual support.

In our experience, instructors better succeed in meeting these expectations when they understand why they matter. Based on AL research, it is no secret that "full adoption of any successful adaptive-learning platform requires faculty buy-in."6 As Johnson and Emma Zone discuss in their EdSurge article "Want Adaptive Learning to Work? Encourage Adaptive Teaching. Here's How," CTU cultivated a culture of innovation by "paying attention to our faculty." As their article outlines, we learned three major lessons:

- Communicate the positives for faculty, not just for students.

- Provide relevant, nimble, and ongoing faculty development.

- Honor the faculty narrative and empower the faculty voice.

Faculty members must understand the AL technology's value and their own role in an AL classroom; it is critical that all stakeholders understand that "faculty who will teach the adaptive learning courses must be in place and on board with the program from the start… training is also key."7 Thus far, CTU has trained more than 1,856 faculty members (60 percent of our total faculty) on the AL platform. Our current AL training covers the basics of teaching in an AL classroom. Based on what we have learned so far, we are now taking the next step and focusing on an instructor-enhanced approach to both versions of the AL classroom.

Moving Beyond Facilitation

One key takeaway from our first six years of working with AL technology is that students learn best when instructors improve the AL technology's personalization by implementing strategic, targeted instructional approaches. Regardless of how much (or how little) classroom content comes from the AL technology, faculty must resist the temptation to focus instruction around classroom components outside the AL environment, thus ignoring the importance of AL-related instruction.

In an AL-enriched classroom, the adaptive assignments often serve to build the foundation for course content, while other classroom assignments — such as discussion boards or individual projects — become the summative assessment of knowledge first developed through the AL content. Focusing instruction solely, or at least largely, on the non-AL classroom components fails to facilitate the necessary transfer of content knowledge outside the AL environment; it also reduces the opportunity for individualization and personalization of the non-AL classroom components.

Instructors must actively work to link the AL content to the non-AL assignments through an individualized, targeted instructional approach both in the AL environment and in other classroom areas. Consider the Professional Written Communications example. In that course, the AL content is designed to prepare students for the non-AL assignments and demonstrate mastery of the course objectives. In Unit 1, for example, the AL lessons focus on the importance of written communication. The AL content introduces basic concepts and correlates to the summative Unit 1 discussion board assignment, in which students provide examples of how they use writing and research daily, discuss their overall comfort level with both, and identify strengths and areas for improvement.

In an all-AL classroom, the adaptive assignments function both as the formative and summative assessment components. Although this makes it harder for instructors to ignore the importance of instruction tied to the AL components of an all-AL classroom, instructors still often seem tempted to focus on those elements outside the AL environment, including synchronous chats and outreach, and ignore the AL content or address it only through practical reminders, such as due dates or missing work reminders.

In an instructor-facilitated classroom such as Academic and Career Success, the engagement that does occur in the AL environment or about AL assignments often takes the form of technology guidance, simple reminders, and group or even canned messages. Rather than taking the time to engage with students in a targeted, individualized way, instructors blast students with robotic messages that may not even apply to them. Worse yet, instructors sometimes lack an understanding of the student experience in the AL environment and thus offer contradictory or counterproductive guidance.

Developing a Model for AL Instruction

An instructor-facilitated AL-augmented classroom does not come close to capitalizing on the potential of the high-quality experience students could be having. To get there, we must develop instructional strategies conducive to the development of instructor-enhanced AL classrooms regardless of whether AL content supplements other assignment types or is the primary assessment method.

At CTU, we are using trial, error, repetition, and data analysis to continually refine faculty expectations and best practices as we develop a specific instructional model for AL-augmented classrooms with differentiations for all-AL and AL-enriched classrooms. Ultimately, instructors must work to develop strategies targeted to each student in four key areas: instructor presence, instructor engagement, content relevancy, and instructional innovation.

The fundamental requirement for instructors is simply to be present in the AL platform. Online classrooms can feel lonely and isolating for students, and instructor presence enhances their experience by creating a sense of connection in both the virtual classroom and the AL platform. Instructors cannot expect student presence throughout the week if they check into the AL platform only sporadically. Students working in AL prize instructor timeliness, and their presence and guidance are key to student engagement and success. Presence should occur both in the AL platform itself — by responding to questions and providing guidance and explanation — as well as by driving engagement outside the AL platform.

However, presence itself is not enough. Instructors must be deliberate in developing effective engagement tactics specific to the AL content. A key component is maintaining an encouraging and positive atmosphere where students feel supported and recognized. While some group messaging can be effective, individualized contact with relevant, applicable messaging for each student is key to guiding students toward personal success; blasting multiple mass messages throughout the week (that may not even pertain to all students) simply leads to confusion or disconnection.

Using the AL platform data and developing routines and basic templates streamlines the process of offering individualized contact with students. Further, analyzing the available student data can help instructors understand student learner habits, leading to opportunities for more effective engagement and outreach. For example, the way instructors engage with students who consistently wait until the last day of the unit to turn in the entire unit's worth of work can and should differ from how instructors engage with students who log in and complete a portion of the assigned work each week. The beauty of most AL platforms is that they offer real-time data and analytics, which makes figuring out these types of behaviors as simple as reading a chart.

Supportive, individualized student-teacher engagement also must be meaningful. A key job of instructors is to guide students in understanding the AL material's relevance to the work in other classroom areas, as well as to future academic work, professional endeavors, and even personal experiences. Instructors should also bring their content expertise into the AL platform to enhance the course curriculum and be active participants in reviewing and maintaining AL content quality.

For example, to increase student understanding of the course content's relevance, instructors can connect specific course topics to current, real-world events or to their own practical professional experiences. Instructors can also leverage AL data and use individualized contact with students to provide specific guidance and resources, such as identifying which lessons students spend the most time on and giving them supplementary resources on those topics.

Many Questions, Great Promise

Overall, AL instructional practices and pedagogy tied to the AL classroom experiences are still very much in the early stages. Instructors must constantly push to innovate and deepen their understanding of how AL technology functions, how they can help students use the AL technology to succeed, and how they can use AL's rich data to improve both their facilitation approach and the learning experience for students.

Although methods can be streamlined as instructors gain experience, there are always new instructional approaches and ideas that can be tested to create better student experiences. AL-augmented classrooms function most effectively when instructors are engaged in using the data that the platform provides. "Adaptive learning offers data every day about all students: when they logged in, how long they were on, what they did, what they repeated, and more. It is up to the instructors to find the data points they value most."8 Feedback from instructors on their AL experiences, including a continual review of AL content and questions, is vital to improving how we use the technology and thus better serve our students' needs. The instructional model for AL-augmented classrooms is developing and improving by leaps and bounds, but we are only beginning this journey. It is a time of more questions than answers, but also of great learning and great promise.

Notes

- Sherry Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age (London: Penguin Press, 2015), 47. ↩

- Gates Bryant, "Learning to Adapt 2.0: The Evolution of Adaptive Learning in Higher Education," Tyton Partners, April 18, 2016. ↩

- "Students ‘Like' Adaptive Learning," BizEd, March 1, 2016. ↩

- Constance Johnson, "Adaptive Learning Platforms: Creating a Path for Success," EDUCAUSE Review, March 7, 2016. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- George Lorenzo, "Failing Forward With Adaptive Learning in Higher Ed," EdSurge, July 21, 2016. ↩

- Barb Freda, "Clearing the Hurdles to Adaptive Learning," University Business, 2016, 39–41. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

Amy Sloan is the Program Chair for the Department of General Education and Psychology at Colorado Technical University.

Lindsey Anderson is the Lead Faculty over Career Planning and Professional Communications for the Department of General Education and Psychology at Colorado Technical University.

© 2018 Amy Sloan and Lindsey Anderson. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.