The five competencies of Creative Know How empower students to escape old ways of doing things, solve current dilemmas, and invent new solutions. In many respects, they are the everyday power tools in the information age.

This article is excerpted and synthesized from Creative Know How—for a Novel, Complex World, Report 8 of the MyWays Student Success Series.

Creative Know How covers a wide range of skills, from those that have always been important (e.g., communication with others) to the ability to work in tandem with highly intelligent machines in ways that serve humanity, where even the questions to be asked are far from clear. Daniel Pink, when asked what he believed was the most important skill in today's environment, responded: "My first instinct is adaptability. You need to be able to change and adapt. I think people have difficulty with that. Dealing with ambiguity has become profoundly important today."1 For this reason, we invite you to keep your eye out, when reading this article, not just for the mastery and craftsmanship involved in the Creative Know How competencies but also for the spirit of innovation and improvisation with which they are approached.

The MyWays Student Success Framework

Higher education leaders are asking important questions about the challenges facing students emerging from secondary and postsecondary education in a world of unprecedented, high-velocity change. What can schools and higher education institutions do to ensure that graduates enter their "wayfinding decade" with the competencies, learning orientation, and agility they'll need to be successful in the 21st century? For that matter, what are those competencies, and how are researchers, social scientists, employers, and educators defining them today?

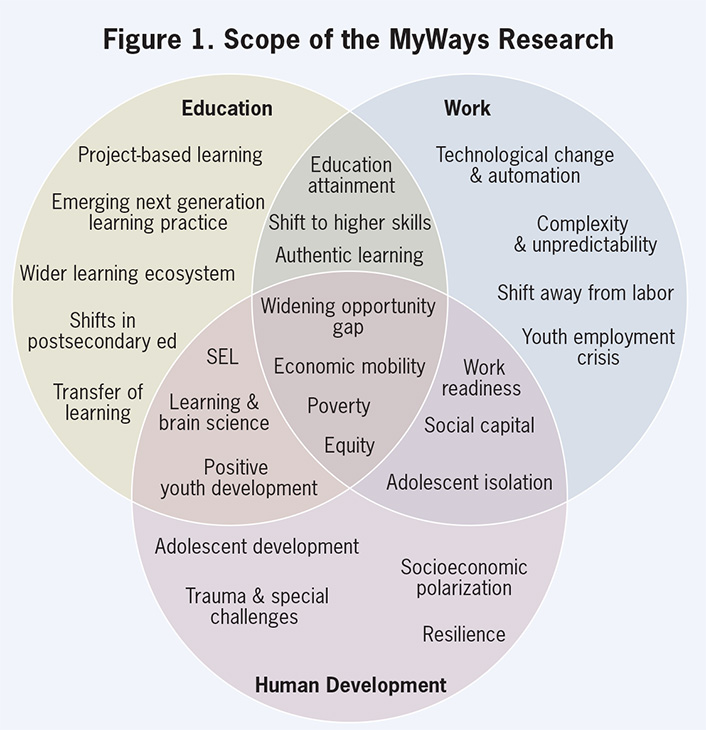

Nearly three years in development, the MyWays project from the EDUCAUSE Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC) initiative was designed to address these issues. It assembles, distills, and presents exhaustive research (see figure 1) on four essential questions that are increasingly taking center stage among elementary and secondary education reformers in the United States:

- Why the urgency to change? What are the profound new realities and conditions that today's students are encountering, and what are their implications for the kinds of competencies students should develop?

- What does success look like for students in a world of accelerating change? What competencies combine to reflect a broader, deeper definition of success?

- How can learning design help students develop these broader, deeper competencies? What implications does a radically different goal line and learning model have for the design of schools and the organizations running them?

- How should schools gauge student progress in developing these competencies? How can we measure and interpret a school's performance beyond proficiency in math and English or language arts to embrace whole-person development?

It is vital that higher education leaders understand these questions, since the answers will shape—and perhaps substantially change—incoming students' readiness to tackle college-level work as well as their expectations about what postsecondary learning should look like.

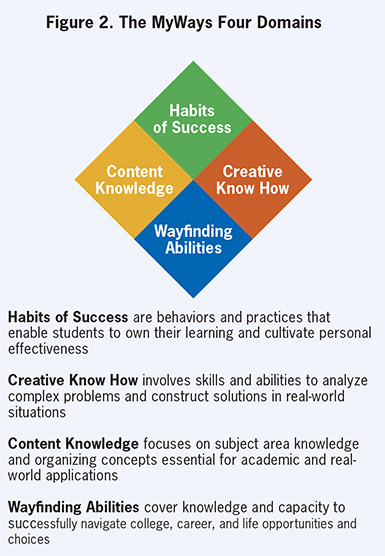

The MyWays Student Success Framework organizes twenty competencies into four domains—Habits of Success, Creative Know How, Content Knowledge, and Wayfinding Abilities—in the voluminous, open-access NGLC MyWays Student Success Series (see figure 2). These domains and competencies are a distilled, integrated composite of more than twenty-five research-based frameworks, composing a "Rosetta Stone" intended not to replace those frameworks but to increase their interoperability. EDUCAUSE Review readers who are familiar with the Lumina Foundation's Degree Qualifications Profile (DQP) will see parallels between that initiative and the MyWays research. Both are efforts to articulate a broadly accepted definition of the skills and dispositions that a diploma should represent—at the college/university and high school levels.

Unpacking, discussing, and applying these questions and this research is becoming of paramount importance to postsecondary institutions as the debate about the value of a college/university education continues to heat up. Higher education institutions could feel the first impacts of these movements in K-12 education soon: an initiative called the Mastery Transcript Consortium is working with independent and (soon) public high schools across the country, along with college/university admissions specialists, to reimagine and redesign the high school transcript around richer, deeper definitions of success—such as those reflected in the MyWays research.

—Andy Calkins, Director

Next Generation Learning Challenges (NGLC) initiative, EDUCAUSE

Why Creative Know How Is So Important

The competencies that compose the Creative Know How domain are important for many reasons, including the fact that they are essential in addressing a range of issues and factors: the roadblocks to employment; the decisions needed to navigate the work/learn landscape; the essentials for cultivating social capital; and the developmental challenges that learners face as they transition to an increasingly volatile world. Students might ask themselves the following:

- Do I have the adaptability, the collaborative and entrepreneurial ability, and the tech/media skills to solve problems, develop new solutions, and create value—for myself, employers, and others in a rapidly changing environment?

- Can I work creatively and effectively with others, of varying backgrounds and skill sets, in face-to-face and digital settings, to help build and sustain teams, networks, and communities?

- Am I able to muster my critical thinking, creativity, and communication skills in pursuit of my postsecondary learning, my early employment opportunities, and my uniquely personal opportunity engine?

- Can I combine all these competencies with my knowledge of the real world around me to make that world a better place?

Creative Know How competencies—continuously coupled with those in the three other MyWays domains (Habits of Success, Content Knowledge, and Wayfinding Abilities)—empower us to escape old ways of doing things, solve current dilemmas, and invent new solutions. In many respects, the Creative Know How competencies are the everyday power tools of the information age.

Essential to Career Bootstrapping

Navigating the work/learn landscape is a perplexing "wicked problem" requiring extraordinary resourcefulness and ingenuity. Most postsecondary students are "working learners" today, but the jobs that many of them find are of only marginal benefit to their careers. More and more workers under the age of thirty are temporary, part-time, contingent, free-lance, or self-employed.2 Skills related to entrepreneurial thinking and creativity are especially in demand in such a world. All workers, even those employed by others, need to use entrepreneurial approaches to do their work and to advance their career. As Tom Friedman has advised: "More is on you."3 Creative Know How competencies play a pivotal role in crafting a personal career-building opportunity engine of work experience, marketable competencies, degrees and credentials, and social capital.4

Coveted by Employers

Creative Know How encompasses most of the value-creating skills that employers, in the aggregate, say they want today. Sixty percent of employers say applicants lack interpersonal and communication skills. Seventy-six percent say 4C-related skills (critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity) will become even more important over the next three to five years. Ninety-three percent say these skills are more important than college major.5 These competencies are also vital to the challenges of automation and artificial intelligence (AI): solving problems that do not have clear answers, that computers and AI address poorly or not at all, and that rely more largely on human-to-human interaction.

Instrumental to Self-Development

Creative Know How competencies shape who we are and how we interact with others and the world. The pursuit of Creative Know How through authentic, active means—through maker spaces, entrepreneurial initiatives, collaborative projects, the use of emerging media, and/or community problem solving via service learning—is a way to put learners out into the adult world, where they can access mentors, see potential paths for interests and careers, and take new steps in their web of development. This aligns with Kurt Fischer's notion that opportunities expand as our know how advances: "Each one of us has our own web of development, where each new step we take opens up a whole range of new possibilities that unfold according to our own individuality."6

Given the importance of meaningful work to both adolescent development and the work/learn cycle, we give Bryan Goodwin and Heather Hein the parting word on why Creative Know How is essential for our learners and our future: "Perhaps the most important pivot we might make (with all due respect to Friedman) is to fret less about how our kids will compete in a flat, hot, and crowded world and more about how they can contribute to that world by solving complex problems. We might start by telling our kids to do their homework because their neighbors—locally and globally—are counting on them."7

The Creative Know How Competencies

The five Creative Know How competencies8 map out the kinds of skills learners will need in order to successfully address the two most pressing challenges of the world they will live in: relentless novelty and deepening complexity. These five skill sets can be developed only through real-world application and iterative practice in a variety of situations that promote transfer. The skills cluster into two groups. The first three competencies correlate well with the popular 4C skills noted above—often referred to as 21st-century skills—with an added emphasis on entrepreneurship for the "more is on you" nature of the gig economy:

- Critical Thinking & Problem Solving: the ability to reason effectively, use systems thinking, and make judgments and decisions toward solving problems in educational, work, and life settings. Addressing this competency includes helping students to identify and define problems and propose solutions using analytical thinking approaches, systems thinking approaches, and design thinking approaches. (Design thinking is also included in the Creativity & Entrepreneurship competency.)

- Creativity & Entrepreneurship: the imagination, inventiveness, and experimentation to achieve new and productive ideas and solutions. Addressing this competency includes helping students to think creatively using design thinking and other approaches, work creatively with others, implement innovation, and develop entrepreneurial skills and mindsets to support new value creation.

- Communication & Collaboration: oral, written, and visual communication skills, as well as the ability to work effectively with diverse teams. Addressing this competency includes helping students to articulate thoughts not only orally but also in writing and nonverbally, listen effectively, use communication for a range of purposes, communicate in diverse environments, work effectively and with respect in diverse teams, show flexibility, assume shared responsibility, and value individual contributions.

Following our research on the full range of competency frameworks and the changes occurring in the economic and social spheres, we were compelled to include two further competency sets to complete the Creative Know How toolkit. First, media and technology are increasingly central to work in any field and to the participation in social and civic life. Second, the brains of twenty-somethings are still developing, and the disorderly gig economy and "more is on you" nature of learning and work paths are likely to pose new challenges to navigate in terms of health, housing, and other practical aspects of living. We therefore added the following Creative Know How competencies:

- Information, Media & Technology Skills: the ability to access, evaluate, manage, create, and disseminate information and media using a wide variety of technology tools. Addressing this competency includes helping students to develop information and media literacy, create media products for appropriate expression in diverse environments, and cultivate technology literacy, including computational knowledge and the ability to leverage the capabilities of augmented and virtual reality, big data, robotics, AI, and other emerging technologies.

- Practical Life Skills: the ability to understand and manage personal finances, health and fitness, and emotional, spiritual, and other aspects of personal well-being to enable and support a productive, effective life. Addressing this competency includes helping students to handle personal finances including credit and debt, manage their health, nutrition, and exercise, attend to their emotional, spiritual, and other aspects of well-being, and address practical life tasks that are evolving fast (e.g., ways to shop, find housing, and get around).

Key Principles for Addressing Creative Know How

Given the existence of a range of 21st-century skills frameworks, what are the distinguishing features of the MyWays Creative Know How domain? Our research tells us that efforts to support Creative Know How should incorporate four key principles:

- Develop and transfer competencies in novel, real-world contexts, incorporating a variety of complex and rapidly changing situations

- Work on skills and knowledge in integrated ways—learners need to apply skills to and through content knowledge, in a virtuous cycle

- Focus explicitly on these skills—naming, practicing, and reflecting on them, as well as being coached on them and receiving ongoing and effective feedback

- Explore the ways in which Creative Know How competencies are intimately interrelated with each other and with the Habits of Success domain

Key Principle 1: Develop and transfer competencies in novel, real-world contexts, incorporating a variety of complex and rapidly changing situations

Change is accelerating in the lives of young adults. In a 2017 keynote address Tom Vander Ark, the author of Getting Smart: How Digital Learning Is Changing the World (2011), underlined how drastic and relentless this change is likely to be. After six months of investigating the state and direction of machine learning and AI, he concluded that the future is likely to bring significant changes and surprises and that what educators really need to "get kids ready for" is "novelty and complexity."9 This echoes the concerns of other thought leaders who refer to the impact on education of some version of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA).10

The concepts of novelty and complexity, and VUCA, have for some time been useful in describing the ways in which applying knowledge and skills in the "messy" realm of the real world differ from learning in a more bounded, inauthentic school setting. Recently, however, the evolution of cognitive computing, the Internet of Things (IoT), the flexible workforce, globalization, and other major paradigm shifts have taken VUCA and its cousin concepts to a whole new level. Vander Ark suggests, for instance, that the 4C skills of the early 2000s (communicating, collaborating, critical thinking, creativity) might now be replaced by a different type of 4Cs that instead describe the nature of the world we live in: "connected, contested, complex, and competitive." The result? As Peter Drucker concluded: "Since we live in an age of innovation, a practical education must prepare a person for work that does not yet exist and cannot yet be clearly defined."11

Promoters of 21st-century skills have always aimed to enhance transfer into novel, authentic situations that a learner might encounter in adult life. Now, as we are realizing that we can't even predict what those situations will be, attention to this approach is even more important. For this reason, Creative Know How requires us to focus on the following: student agency; real-world authentic learning; the availability of diverse opportunities to apply and improve competencies in iterative ways; a focus on contextual reasoning and conditional knowledge (which "includes knowing when and why to apply various actions")12; and of course, the goal of transfer itself (i.e., knowing how to apply those actions). In Four-Dimensional Education: The Competencies Learners Need to Succeed, Charles Fadel, Maya Bialik, and Bernie Trilling observe: "Research has shown that educational environments that emphasize students' active roles, that enhance students' self-regulation, that encourage communication and reflection skills, and are social and relevant to the learner (character qualities), successfully enhance the transfer of learning to new situations." The authors add: "In fact, the elusive goal of education transfer—applying what one learns in one setting to another different context—can be thought of as preparation for future learning. This view redefines learning transfer as the productive use of skills and motivations, to prepare students to learn in novel, real-world situations, or in resource-rich environments."13

Key Principle 2: Work on skills and knowledge in integrated ways — learners need to apply skills to and through content knowledge, learning both more deeply, in a virtuous cycle

Fadel, Bialik, and Trilling wisely note the following: "A long-standing debate in education hinges on an assumption that teaching skills will detract from teaching content knowledge. We believe this is a . . . false dichotomy. Studies have shown that when knowledge is learned passively, without engaging skills, it is often only learned at a superficial level (the knowledge may be memorized but not understood, not easily reusable, or short-lived), and therefore not readily transferred to new environments. Deep understanding and application to the real world will occur only by applying skills to content knowledge, so that each enhances the other." Knowledge and skills, they continue, develop together "in a virtuous cycle." For example, knowledge "becomes the source of creativity, the subject of critical thought and communication, and the impetus for collaboration."14

For a glimpse of how this cycle can work, see the Partnership for 21st Century Learning (P21) Skills Maps, which illustrate the intersection between 21st-century skills and the traditional content knowledge subjects of math, science, social studies, geography, English, languages, and the arts. These maps, developed with key national organizations that represent each core academic subject, provide concrete examples of learning experiences and outcomes at gateway grade levels—examples that integrate skills development in "authentic ways that enhance—not replace—robust science [or other subject] content."15 Skill development in any one instance is embedded in the content-based learning activity, while the opportunity for transfer is increased by practicing the skill in multiple, varied learning experiences and by undertaking explicit coaching and reflection that adds a metacognitive element to learning the skill (see Key Principle 3).

Key Principle 3: Focus explicitly on these skills — naming, practicing, and reflecting on them, as well as being coached on them and receiving ongoing and effective feedback

In the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Skill to do comes of doing."16 Creative Know How skills are intellectual "muscles" that can be genuinely strengthened only through doing and practice and not exclusively through study—much like, say, taking good photos or kicking a football. Yet just "collaborating" or "problem solving" as part of learning experiences, like just throwing a football around with your cousins, is unlikely to lead either to optimal progress in mastering the competency or to a better chance of transferring that skill into novel situations.

Educators helping students to develop Creative Know How need to help the learners recognize, develop vocabulary for, and practice the skill, as well as to provide them with ongoing and effective feedback on these efforts. They also need to coach and model the skill, exposing learners to a novice-to-expert progression that moves from structured rules through analysis to intuition; from tinkering through focused practice to fluid expression; and from controlled context through near transfer to far transfer.17

Finally, in Creative Know How, learners need the means to collect evidence of process as much as product. Most importantly, learners need a structure to help them reflect on their progress in Creative Know How competencies, because reflection and metacognition are particularly important in enhancing transfer.

Key Principle 4: Explore the ways in which Creative Know How competencies are intimately interrelated with each other and with the Habits of Success

Within competencies consisting of linked skills—such as Critical Thinking & Problem Solving or Creativity & Entrepreneurship—the pairs are intimately interrelated, even as they feature elements of their own. Indeed, even across the five competencies in each domain and the twenty competencies across domains, there is overlap in some aspects. While the framework is useful for designing goals and tracking attention and progress, it is not always possible or desirable to try to tease out the threads of one competency from the other for the purposes of learning or, in particular, assessment. The value of MyWays lies in its use for planning and tracking the availability of learning experiences within which students can develop, practice, and reflect on their progress in the various competencies.

A particularly strong synergy exists between Creative Know How and another MyWays domain: Habits of Success. Because both can be developed and practiced only within active, authentic learning, their competencies are often interwoven. The Habits of Success, for example, which include those competencies related to students' social-emotional health, directly impact students' creativity, their critical thinking skills, and how students collaborate. We should also highlight that self-directed learning, a competency often grouped with 21st-century skills in other frameworks, appears in the MyWays Habits of Success domain. We placed it there because self-directed learning is central to the Habits of Success, which focus on "behaviors and practices that enable students to own their learning and cultivate personal effectiveness." Of course, placement in a conceptual model in no way separates competencies in the real world of learning and work.

Conclusion: Skills and Improvisation

"To be successful in the emerging society and economy, young people will need skills that previous generations did not. They will need to solve problems that do not have clear answers and that computers address poorly, if at all. . . . It's not just jazz musicians who need to learn how to improvise."

—Elliot Washor and Charles Mojkowski, Leaving to Learn18

The Partnership for 21st Century Learning (P21) came out with its framework of 21st-century skills more than a decade ago. While the skills it outlined were not new, the movement it launched succeeded in establishing the need for schools to address "know how" as well as knowledge. Ten years later, we are beginning to realize just how creative (or adaptive and transferable) that know how must be to prepare learners, in essence, for the unknown—for jobs not yet invented, for the impact of AI, and for engaging with others in ways that evolve every few years.

Already we see glimpses. Who was expecting the major impact of robots and AI? By 2033 (about when today's first-graders will finish four-year degrees or apprenticeships), economists predict that tech innovation could convert 30 percent of existing occupations into services completed "on demand" through a mix of cognitive computing and human labor.19 With the rapid evolution of AI, these will include "thinking" as well as "doing" jobs—from med techs and paralegals to marketers and financial advisors. Indeed, IBM's Watson is solving medical cases that doctors cannot. Those who want to stay relevant in their professions will need to focus both on motivating and interacting with human beings and on working with AI.20

Or, indeed, who was expecting the disruptive power of fake news? Media literacy, a growing concern for over a decade, became a hot issue during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Increasing reports of "fake news" coincided with attention to research indicating just how ill-equipped young people are to critically evaluate information they encounter online and via social media. A Stanford team, led by Sam Wineburg and Sarah Cotcamp McGrew, field-tested news-literacy tasks of varying difficulty. More than 80 percent of middle-schoolers were unable to distinguish a "native advertisement" (ads masquerading as articles) from real news, and nearly 70 percent of high-schoolers identified a Shell advertisement on climate change as a more reliable source of information than an Atlantic magazine news article.21

Preparing for the increasing number of such hard-to-predict, consequential developments—in other words, learning to improvise—will always be an art rather than a science. But it requires skills and competencies. How to address the challenge of AI? Have a look at the Creative Know How competencies of Critical Thinking & Problem Solving, Creativity & Entrepreneurship, and Communication & Collaboration. How to tackle false news? Cue Critical Thinking & Problem Solving, Communication & Collaboration, Information, Media & Technology Skills, and Practical Life Skills.

Some worry that the focus on Creative Know How is overly driven by economic changes and vocational concerns. We see a bright side. Twenty years ago, the educational psychologist Lauren Resnick reflected on the "high-performance workplace," which "calls for the same kind of person that Horace Mann and John Dewey sought: someone able to analyze a situation, make reasoned judgements, communicate well, engage with others to reason through differences of opinion, and intelligently employ the complex tools and technologies that can liberate or enslave, according to use . . . people who can learn new skills and knowledge as conditions change—lifelong learners, in short." In this world of change, "preparation for work and preparation for civic and personal life no longer need be in competition."22 We strongly believe that the five Creative Know How competencies are the basis for this kind of preparation.

Notes

- Daniel Pink quoted in Bill Sheridan, "Today's Top Skills: Adaptability, Lifelong Learning," MACPA (website), November 1, 2012. ↩

- For more information, see: MyWays Report 2, 5 Roadblocks to Bootstrapping a Career; Robert Kuttner, "Why Liberals Have to Be Radicals," The Amercian Prospect, July 21, 2015; Gerald Friedman, "Dog Walking and College Teaching: The Rise of the American Gig Economy," Dollars & Sense, March/April 2014. ↩

- Thomas L. Friedman, Thank You for Being Late: An Optimist's Guide to Thriving in the Age of Accelerations (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), 229. See also the discussion in MyWays Report 10, Wayfinding Abilities for Destinations Unknown. ↩

- For more on the opportunity engine, see MyWays Report 2, 5 Roadblocks to Bootstrapping a Career, and Report 3, 5 Decisions in Navigating the Work/Learn Landscape. ↩

- Martha C. White, "The Real Reason New College Grads Can't Get Hired," Time, November 10, 2013; National Education Association, "Preparing 21st Century Students for A Global Society: An Educator's Guide to the 'Four Cs'" (n.d.); Hart Research Associates, It Takes More Than a Major: Employer Priorities for College Learning and Student Success (Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2013). ↩

- Kurt Fischer quoted in Todd Rose, The End of Average: How We Succeed in a World That Values Sameness (New York: HarperOne, 2015), 138. ↩

- Bryan Goodwin and Heather Hein, "Research Matters: What Skills Do Students Really Need for a Global Economy?" Educational Leadership 74, no. 4 (December 2016/January 2017), emphasis added. ↩

- For expanded descriptions of each competency, see the one-page competency primers at the end of Report 8, Creative Know How—for a Novel, Complex World. ↩

- Tom Vander Ark, "The State of the Edtech Marketplace," LearnLaunch Across Boundaries conference, Boston, February 2, 2017. ↩

- Use of the VUCA acronym derives from a 1990s U.S military study analyzing the implications of rapid change brought about by the information age. For a business take on VUCA, see Nathan Bennett and G. James Lemoine, "What VUCA Really Means for You," Harvard Business Review, January-February 2014; for the psychological perspective, see Michael Woodward's interview of David Smith, "How to Thrive in a VUCA World: The Psychology of Navigating Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous Times," Spotting Opportunity (blog), Psychology Today, July 31, 2017. Both of these approaches share a lot of characteristics with core concepts embedded in the four MyWays competency domains, as well as the kind of adaptability, big-picture view, and design thinking underlying MyWays learning design. ↩

- Vander Ark, "The State of the Edtech Marketplace"; Tom VanderArk, "Five Trends Demand Smart States," Vander Ark on Innovation (blog), Education Week, June 1, 2015; Peter Drucker, quoted in Bernie Trilling and Charles Fadel, 21st Century Skills: Learning for Life in Our Times (San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, 2009), 151. ↩

- Scott G. Paris, Marjorie Y. Lipson, and Karen K. Wixson, "Becoming a Strategic Reader," Contemporary Educational Psychology 8, no. 3 (July 1983), quoted in Grant Wiggins, "On Reading, Part 5: A Key Flaw in Using the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model," Granted, and... (blog), March 30, 2015. ↩

- Charles Fadel, Maya Bialik, and Bernie Trilling, Four-Dimensional Education: The Competencies Learners Need to Succeed (Boston: Center for Curriculum Redesign, 2015), 105–106. ↩

- Fadel, Bialik, and Trilling, Four-Dimensional Education, 106, 121.↩

- P21 Skills Map for Science. ↩

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Old Age," Atlantic Monthly, January 1862. ↩

- For more on the novice-to-expert progression, see the "Levers for Capability and Agency" section in Report 11, Learning Design for Broader, Deeper Competencies. ↩

- Elliot Washor and Charles Mojkowski, Leaving to Learn: How Out-of-School Learning Increases Student Engagement and Reduces Dropout Rates (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2013), 58, 73. ↩

- Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri, "The Humans Working Behind the AI Curtain," Harvard Business Review, January 9, 2017. ↩

- Megan Beck and Barry Libert, "The Rise of AI Makes Emotional Intelligence More Important," Harvard Business Review, February 15, 2017. ↩

- This paragraph summarizes reports on the Stanford study and other research from Benjamin Herold, "'Fake News,' Bogus Tweets Raise Stakes for Media Literacy," Education Week, December 8, 2016, and Chris Berdik, "How to Teach High-School Students to Spot Fake News," Slate, December 21, 2016. For the Executive Summary of the Stanford report, see Evaluating Information: The Cornerstone of Civic Online Reasoning, Stanford History Education Group. ↩

- Lauren B. Resnick, "Getting to Work: Thoughts on the Function and Form of School-to-Work Transition," in Transitions in Work and Learning: Implications for Assessment, ed. Alan Lesgold, Michael J. Feuer, and Allison M. Black (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1997), 258. ↩

Grace Belfiore is Principal Consultant at Belfiore Education Consulting.

Dave Lash is Principal at Dave Lash & Company.

© 2018 EDUCAUSE. The text of this work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

EDUCAUSE Review 53, no. 2 (March/April 2018)