IT leaders describe how their institutions are building technology strategy that enables a next generation enterprise IT approach.

This article is the first in a 2018 series that presents case studies related to the theme of next generation enterprise IT:

-

Building a Technology Strategy to Enable Next Generation IT

-

Connecting Enterprise IT Models to Institutional Missions and Goals

-

Understanding the Shifting Role of IT in Institutional Sourcing Decisions

-

Maintaining Business Process Redesign Efforts through Change Management

-

Using Data from Multiple Systems for Personalized Study Experiences

Traditional enterprise IT can be considered centralized, monolithic, and vendor-driven. Next generation enterprise IT, on the other hand, is characterized by a movement beyond siloed, transactional systems to a multifaceted, interconnected ecosystem that substantively contributes to and advances the mission and effectiveness of the institution. Because end users are essential to the success of next generation enterprise IT, it is mission-driven and client-centric. It is enabled by a variety of trends in technology and its management that include cloud computing, business process reengineering, social networks, mobile technologies, analytics, artificial intelligence, enterprise architecture, and service management methodologies. It is driven by the migration of authority and responsibility closer to the edges of organizations, and by expectations such as hyper-personalization of services, a closer link between IT and the institutional mission and goals, and greater system agility, flexibility, and scalability. These trends and drivers are pushing us to rethink enterprise IT.

To take advantage of emerging trends and to meet expectations, IT faces several challenges that the Enterprise IT Program will consider throughout 2018. In this first set of case studies, IT leaders from University of the Pacific and Pomona College take a look at the challenge of technology strategy, and they consider ways to position their institutions for success. Developing an effective technology strategy requires a deeper understanding than ever before of institutional culture and the needs of the business unit. And because it involves an ever-expanding set of systems and applications, data integration and data governance efforts are critical, along with the ability to be flexible and nimble enough to adapt to the disparate data sources as they emerge.

University of the Pacific

Peggy Kay, Assistant Vice President, Technology Customer Experience

Institutional Profile

University of the Pacific is a nationally ranked university with three distinct campuses united under one common goal: to educate and prepare the leaders of tomorrow through intensive academic study, experiential learning, and service to the community. Drawing on its rich legacy as the first chartered university in California, Pacific is a student-focused, comprehensive educational institution that produces outstanding graduates who are prepared for personal and professional success. Our student body thrives in Pacific's small classes and dynamic cultural environment, while our distinguished alumni are transforming their communities every day.

Overview

Most universities spend significant time developing a master/strategic plan for their facilities, often reflected in a consistent "look and feel" to buildings on campus. That same sense of context is not often used by institutions when creating a strategy for technology. Often the strategic part of a technology master plan is more a vehicle for phasing and funding tactical projects. Creating context for technology strategy involves working with university leaders, stakeholders, and team members to help create a shared understanding of the present state of technology on campus, how it appears and functions within the community, and how it provides a cross section of the long-term and short-term needs and goals for planning. A shared understanding that connects people to the strategy enables an organization to fulfill its mission. Pacific Technology is following a strategic methodology of creating its plans in the context of outcomes specifically related to operational excellence and innovation.

In August 2013, University of the Pacific's president and her executive team recognized the strategic importance of technology and convened a review by external consultants to examine the operations and capabilities of the technology department. This review resulted in the following:

- Recognition of a need for all university leadership within and external to the technology department to fully embrace ownership of the technology directly affecting their unit. As a result, university leadership acknowledged technology ownership, and this improved capacity for scheduling of projects and created a safer environment for controlled failure and recovery.

- Creation of the first vice president for Pacific Technology directly reporting to the president. This raised the visibility of the strategic importance of technology at the university.

- Creation of an ad hoc technology committee for the university board of regents. This provides oversight, guidance, and advocacy to university technology initiatives.

- Creation of internal technology university governance that is achieved by the Information Strategy and Policy Committee, which acts as an advisory group composed of a cross section of university constituents.

- Development of the first technology strategic plan for the university. This provides context for all future technology-based initiatives.

Developing the Pacific Technology Strategic Plan

As a result of the technology organization review in 2013, an interim Pacific Technology CIO was appointed to lead and assess the department. The initial focus of building the technology strategy was based on aligning the initiatives with the university's goals. It also included:

- Meeting with various university stakeholders

- Assessing the current state of Pacific Technology and the department, including people, processes, and tools

- Understanding the university's strategy, including the political, economic, social and technology impacts

- Analyzing emerging technologies

- Defining IT initiatives to map to university goals

- Developing the strategy roadmap, including risk assessment and stakeholder buy-in and approval

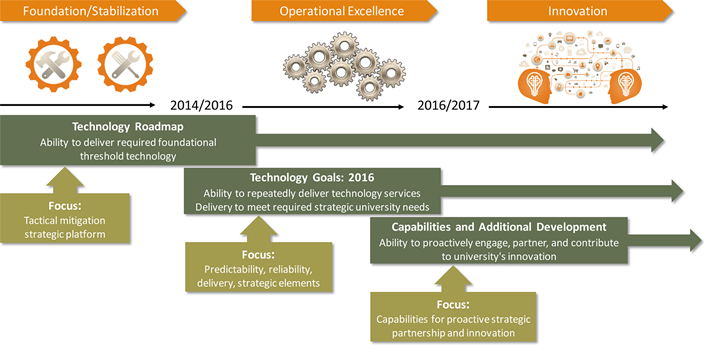

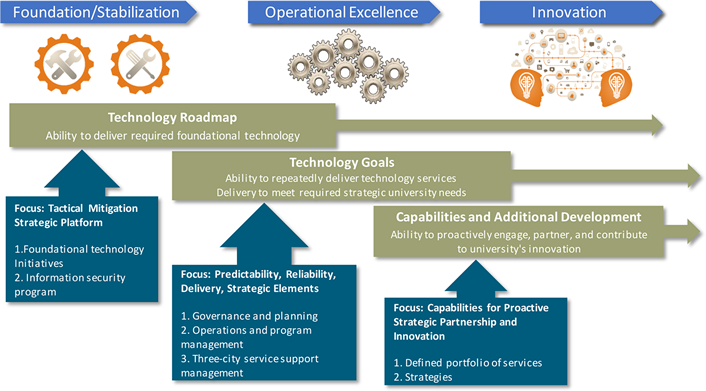

Assessment of the current state of Pacific Technology (see figure 1) revealed foundational issues across the technology department that needed to be addressed. The principal strategy focused on strengthening foundational technology while improving operational performance to create a culture of innovation. The focus for the first two years was on stabilizing the technology infrastructure as well as moving the technology organization to ITIL to improve overall practices. These efforts, combined with a series of meetings with university leadership on the need for technology governance, slowly turned the Pacific Technology organization in a new direction.

In July 2015, the university hired its first vice president of technology, reporting to the president. Our new CIO, Art Sprecher, reviewed the defined strategy and roadmap, and expanded our strategic direction through an organizational change that introduced technology enterprise architecture and customer experience, information security and risk management, and strategy and planning groups. This organizational change provided a structured focus for technology planning and end-user improvements (see figure 2). Within the context of our outcomes planning model, each department targeted its planning in two dimensions, university institutional priorities and divisional goals, as follows:

University Institutional Priorities:

- Becoming a three-city university

- Student success

- Building the quality and reputation of academics

- Developing the talent within our organization

- Empowering our future through our fundraising campaign

Divisional Goals:

- Emphasize the importance of the customer experience

- Build organizational foundation for operational excellence guided by a robust technology architecture

- Expand our capabilities for managing Information security risk

- Develop our capacity for planning and innovation

- Enable the engagement of all Pacific Technology team members

- Successfully deliver specific customer and technology projects

For the last two years, Pacific Technology departments have developed fiscal-year operational plans in support of the goals and objectives of the university and the division strategy. An operational governance activity was also defined to ensure we are controlling and coordinating our activities to operate effectively, work as an aligned team, and make progress toward our desired outcomes. We identified three levels of performance that we must maintain while working with our limited pool of staff and contractors, as well as finite funding. These levels include

- Consistent day-to-day delivery of operational services

- Management of initiatives, programs, and projects focused on the change and growth of the division as a technology and services organization

- Management and facilitation of programs and projects required by the university as a whole

Lessons Learned

We are implementing our outcomes-based strategy. We would like to see the strategy executed at a faster pace to achieve the desired success for our constituents. We are discovering obstacles and working to address them. We've seen progress on partnerships for new academic program development. Where we once were brought in toward the end of the program development, we are now part of the team developing and scoping the program. Having visibility at all levels of the university is key to achieving our defined outcomes.

Here are a few of the lessons we've learned in developing our strategy:

- It's not enough for us as leaders to talk about the context or even provide examples of context to execute on strategy. These tasks are the work of every individual who contributes to the achievement of our strategy. Managers need to be communicating with their teams on how they are directly affecting the achievement of strategic goals in their day-to-day work.

- Working with university stakeholders needs to extend beyond just the formal tabletop meetings. We need to go to their meetings with their teams to discuss and create shared understandings of goals and set direction.

- Understanding the skills and abilities of team members is also a key factor in executing strategy. Assumptions that either overestimate or underestimate the skill of a team member can affect timelines and execution.

- An engaged university governance committee is an extremely helpful partner for advice and feedback on university technology direction and can foster a shared environment of technology ownership.

Pomona College

William Morse, Vice President and Chief Information Officer

Institutional Profile

Located in Claremont, California, Pomona College is widely regarded as one of the nation's premier liberal arts colleges. Established in 1887, Pomona College is the founding member of The Claremont Colleges, a unique consortium of seven colleges and graduate schools, offering the advantages of a small liberal arts college and the resources of a large university. Pomona is home to about 1,650 students.

IT Strategy for Next Generation IT

Anyone who works in higher education IT these days will tell you that we are living in absolutely amazing times. The proliferation of targeted, micro best-of-breed applications in the cloud is empowering offices outside of IT to be self-sufficient and entrepreneurial beyond what they could have imagined just a few years ago. The excitement this is generating has awakened people to the long-held promise and power of IT. They all want to move forward — and quickly. The troubling issue is that this desire to move forward involves every office at the institution at the exact same time. This can be overwhelming to a traditional IT unit, even frightening.

So, what is an IT unit to do? Just like so many times in the past, it is time to evolve.

The first point to recognize is that central IT units absolutely still have a critical role to play. It is their duty to look over the entire institution and take all needs into account. It is they who have the responsibility to see that the institution's data are secure, that there are clear systems of record, and that the overall architecture of enterprise systems makes some sort of coherent sense. It is their job to bring the various offices together to see if there are synergies to be had with all these new tools, and to look for overlap and try to see if offices can leverage tools together. IT also has to build an internal architecture that is flexible and robust enough to work under the new paradigm.

To meet these needs, the IT unit must understand that it will likely have to change. As painful as it might be for some, the central IT unit of the future is very unlikely to be directly delivering services as it did in the past. Yes, there will still need to be a central core to bring all the services together, and it is IT that needs to take a holistic look at the various technology tools the institution offers. IT units will be coordinators and consultants; their job will be to design a security, integrations, analytics, and data architecture that is flexible and robust enough to work in a micro best-of-breed world. IT will need to ask questions such as: Do all these tools work together coherently? Are they easy to use when taken together, or are we deploying so many different unrelated things that we have just created "IT noise" for our constituents? Has our infrastructure become too much, too complex for our end users?

For an IT unit to meet the needs of the future, it has to address the following concerns: governance, project management, security, integrations, and data architecture. In addressing these issues, the goal is to create transparency, engagement, and effectiveness. It is definitely not meant to set up unnecessary bureaucracy or roadblocks that have the effect of keeping offices from moving forward with their ideas. After all, an IT unit should want other offices to come to them for assistance. Offices will only do that if they trust the IT unit and have faith that it will diligently help them achieve their goals. If IT cannot offer that, people will work around IT instead of through IT.

Governance

A lot of IT units struggle with governance. Of particular difficulty is striking the balance between useful, important input versus micromanagement direction. It is a difficult needle to thread. If participants on the governance committee do not feel their input is valued, a governance structure can quickly fall apart no matter how well designed. However, there are times when IT needs to do unpopular things that are simply for the good of the institution. The IT governance structure should not be in a position to stop necessary work. Collaboration and transparency are key tools that can yield success in this push-and-pull environment. If IT units can explain what they are doing and why, that will generally earn the trust of the community and allow IT to do what needs to be done.

However, as difficult as it is to get right, governance is absolutely essential for IT to be successful in the micro best-of-breed world. The reason is actually quite simple: Good IT governance brings the institution together. Done well, IT governance is the place where various institutional offices sit down and discuss IT solutions holistically. It is the place where questions of "how does all this fit together?" can be asked and resolved. It is the place where offices can ideally put their particular interests aside and look to the greater institutional good.

The ultimate goal, of course, is to use the committee to help IT develop a comprehensive IT architecture. That architecture will, in turn, help the IT unit know how it is going to get things done. It will bring synergy across the services IT offers and almost certainly make the use of those services more coherent to the community.

Here at Pomona College, we have an overarching governance committee that gives feedback across all the services we offer, administrative, educational technology, or otherwise. This committee is where strategic issues are discussed and feedback is taken. We also have a variety of subcommittees that deal with specific areas of concern. For example, we have a faculty committee that is helping guide our research computing initiative. We also have a dedicated committee for our administrative systems, and soon we'll have one for educational technology.

With each of these committees, transparency and engagement are keys to our success. That builds trust. In addition, we actively report back to the committees how their input affects what we are doing or have done. That is what makes people want to participate: They know what they think matters.

Project Management

As part of the transition to a more service-oriented, consultative department, the development of a project management methodology and culture within the IT unit is absolutely essential. The best way to do this, even at small institutions like Pomona College, is through a true Project Management Office (PMO).

Why does all this matter? With the proliferation of micro best-of-breed applications, there are a lot of demands on the IT unit to bring things to production quickly. A department can literally have dozens of requests processing simultaneously in the project queue. Without good project management methodology and the process structure that goes with it, an IT unit can quickly find itself overwhelmed by the sheer number of requests it gets.

Project management methodology and the PMO that operationalizes that methodology provide the solution to managing both the prioritization of the workload and the entirety of the portfolio itself. They create the processes and the procedures for project intake, needs assessment, scope documentation, and more. They also provide the workflow to ensure projects get a proper technical overview, including a security assessment and an integrations and data architecture review. Finally, they manage the flow of projects to ensure things get done in a timely manner that offices can rely on, and they prevent the department from being overwhelmed such that work becomes nothing more than a game of whack-a-mole.

Here at Pomona, our PMO does all of these things and more. In addition, it operationalizes our governance committees and is primarily responsible for the presentations to those groups when projects come up for approval. This brings consistency, efficiency, and order to the process. Offices appreciate the support they get bringing their projects through the process.

That said, some have noted that all this process looks bureaucratic. On paper, it does. However, a consistent and transparent approval process actually smooths the path of project approval. Everyone knows how things get done, and that makes it easier for all.

Security

Like it or not, security is going to be of ever-increasing importance to every higher education IT unit. Yes, it is frustrating, because investments in security do not obviously translate into improved services to the institution. Further, security is a multi-FTE effort with very expensive support needs. Yet it is also a fact of life. No CIO wants to be on the front page of a local or national newspaper because of a security breach at their institution. More importantly, investing in this area is the right thing to do. It is, frankly, what is needed to protect the community in a pretty daunting internet world.

A focus on security is uniquely important with administrative systems, particularly because many are hosted entirely in the cloud. Just because a contract exists between an institution and a cloud provider does not mean that the IT unit can absolve itself of security responsibilities. Indeed, the IT unit's responsibility for security is even more important in the cloud context. After all, a breach of institutional data from a cloud provider is your breach. With a vendor relationship, protecting the institution starts right at the beginning, before a contract is even signed.

At Pomona College, we have a comprehensive survey we ask every prospective vendor to complete. The survey does not deal with just the obvious security issues (backups, data protection strategies, disaster recovery, etc.); it also covers issues of company viability and our own ability to recover should the firm suddenly cease operations. After all, a lot of these new micro best-of-breed solutions are coming from very small vendors. We want to reasonably take advantage of their creativity while protecting ourselves and our community's data. In addition, we have standard contract terms that we ask all our vendors to accept. We worked with our lawyers to make the terms reasonable and fair, which in turn has made them much more acceptable to our prospective vendor partners. This has helped us get the terms we want in the contract without overly drawing out the contract negotiating process.

Finally, we periodically review our vendors and are particularly attuned to warning signs. If a company stops being responsive, if their platform becomes unstable, and if update deadlines start being missed, the team should reasonably expect that security is also a problem. It might be time to look elsewhere.

Integrations and Data Architecture

In a micro best-of-breed world, the issue of integrations and data architecture quickly becomes a top priority. The reasons for this are twofold.

First, without a comprehensive strategy, the sheer number of integrations in a micro best-of-breed environment can become overwhelming in both the origination of the integrations themselves and the long-term maintenance of those integrations. The IT department definitely does not want to be in a position where they have to proverbially recreate the wheel every time they do a new integration, nor does it wish to have integrations done inconsistently, which would greatly increase maintenance costs. To address these concerns, IT should have a well-formulated strategy and a standard architecture for doing integrations. In addition, an integration broker―a system that manages all the integrations holistically―might be a wise investment. Finally, having a standard structure in place is also important for maintaining security standards.

Second, analytics depends on the strategic flow of information among the various administrative systems. In most cases, when two systems are integrated, that integration passes on only the data needed for the next system to complete the transaction. However, analytics depends on a richness of data that is often lost when the goal is simply to get transactional systems to work together. This issue becomes compounded as more and more systems are brought together. The answer to this problem is, again, to think strategically about how data flows within administrative systems. What data would be valuable for the analytics systems? How can the richness of data be preserved as data flows through various systems?

At Pomona, we are looking to address both issues. Through the Claremont Consortium, we are collaborating with other institutions to select a common integration broker that we will all use with our core administrative system. In addition, we are strongly considering adding the position of data architect to the IT team to help us be intentional with data flow as we build integrations. This in turn will ensure that the analytics program has full access to the complete richness of the data.

Lessons Learned

If there is one thing those of us who work in IT can count on, it is this: Change will always be constant. That has never been truer than now, with the rise of cloud-based micro best-of-breed applications. They are empowering campus offices, making IT services richer, and changing the very nature of what an IT unit should be and can do. In the end, this will make IT more important to the institution. It will be IT that helps offices leverage these tools effectively, safely, and in a way that works throughout the institution. These are truly exciting times, and that makes it a great time to be in IT.

***

Effective technology strategies are characterized by a close alignment of IT and overall institutional mission. The case studies in this article describe their institutions' efforts to achieve that alignment and develop technology strategies that position themselves for the kinds of deeper technology engagement that come with next generation enterprise IT. The authors note that IT governance is a critical piece of their success, and they stress that the process must be transparent and engaging. Other important considerations for a successful technology strategy include close attention to data security, an understanding of the importance of data integration, and the use of a framework such as project management. Finally, authors noted that this work is not just for IT leaders. The close alignment of IT and institutional mission means that every individual should be able to understand how their work contributes to institutional goals.

Peggy Kay is Assistant Vice President, Technology Customer Experience, at University of the Pacific.

William Morse is Vice President and Chief Information Officer at Pomona College.

© 2018 Peggy Kay and William Morse. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.