Today, websites must be designed to raise the international profile of institutions and clearly communicate their mission.

We hear much about both globalization and internationalization today, but while the two terms are related, they have distinct meanings in the higher education context. Globalization refers to the 21st century's economic and academic trends.1 In higher education, globalization refers to many trends—including the emergence of the "knowledge society" as result of global capital investments, dependency on knowledge products and highly educated personnel for economic growth, the use of English as the lingua franca for scientific communication, and the rise of e-learning providers offering academic programs—that tend to concentrate wealth, knowledge, and power in the hands of those already possessing them.

In contrast, internationalization in higher education refers to a range of academic practices and programs aimed at increasing collaboration, student diversity, and institutional growth. Among these practices and programs are study abroad, international student recruitment and enrollment, faculty mobility, distance education, research and scholarly collaboration, and extracurricular programs that include an international and intercultural dimension.2, 3

According to an International Association of Universities survey, 53 percent of the 1,336 higher education institutions surveyed across 131 countries have an international policy/strategy, while 22 percent are preparing one. Further, 61 percent have a dedicated budget for internationalization and 66 percent have explicit targets and benchmarks to assess their internationalization policy implementation.

Clearly, internationalization has become an integral part of higher education's continuous change process — and is increasingly the central motor of that change. As such, it offers new opportunities and poses new challenges.4 Among those challenges are finding ways to communicate the value of an institution and its programs to a global audience. Enter the institution's website. Although once aimed primarily at local, regional, or national audiences, websites today must be designed to serve broader international aims. This typically means including content written in English, which is the standard language for international collaboration.

As described here, I explored this issue through a study of higher education websites in Spanish-speaking countries. I also investigated and identified best practices for creating websites to capitalize on internationalization opportunities.

The Website's Importance

Young adults use the internet more frequently and for longer time periods than other groups. Millennials are known for their advanced access to and use of the internet, and this trend is expected to continue and increase in importance as Generations X and Y become parents.5 An experience described in a University of Kansas blog exemplifies the role of a higher education institution's website in our increasingly internet-centric world: "When I was looking at universities at which to apply, their websites did make an impact on me. Granted, their website was not as important to me as the credentials of the school, but it did make a difference in how I viewed the school."6

Institutional websites give site visitors — including prospective and current students, prospective and current faculty, researchers, parents, alumni, employers, and companies — information about a university.7 They also reflect the institution's style, activities, and reputation.8

In one study, 94 percent of student participants responded positively to the statement: Prior to considering a school, I examine its website.9 Such a response rate highlights the importance of having an attractive, clear website that acts as a tool to "sell" the institution. That goal has become even more challenging in today's highly collaborative world, where content must make that sale across cultures and national boundaries.

A Study of Ibero-American University Websites

As Simon Marginson and Marijk van der Wende confirmed in their work, higher education is a globally competitive, asymmetrically resourced market dominated by the dynamics of the English language.10 Further, since 2004, the Webometrics Ranking Web of Universities has been performing a scientific exercise in cooperation with the Spanish National Research Council's Cybermetrics Lab to provide information on international universities' web presence and impact. In their decalogue of good practices for institutional web positioning,11 Webometrics recommends using English, advising universities to think both locally and globally by offering selected sections for an international audience.

Inspired by this work and my experiences attending international conferences, I decided to investigate the websites of Ibero-American universities — that is, universities in Spanish-speaking countries — to identify whether their websites offered information in English, and if so, whether that content was suitable to an international audience.

I further studied the universities' technologies, information systems, innovations, and practices that impact internationalization. Among my findings were that most Ibero-American universities with relatively high international rankings include substantial English-language content on their websites.

Language and Global Reach

While attending international conferences, I learned that people were interested in engaging with institutions in Ibero-America but that they had trouble doing so when online information was offered only in Spanish. In fact, during one Spanish-language presentation I attended, the speaker noted that: "If your information is not in English, you are invisible to the rest of the world."

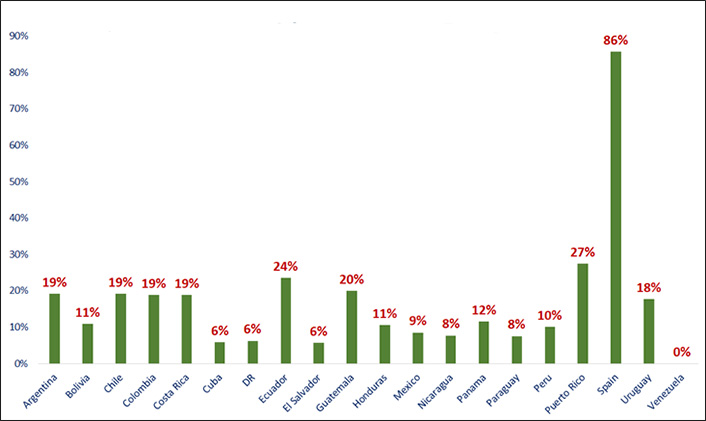

To determine the extent of this language issue, I examined 1,881 institutional websites from 20 countries in Ibero-America. Figure 1 shows results on the availability of information in English: On average, only 13 percent of the institutions in Ibero-America have information in English; in contrast, 86 percent of universities in Spain have information in English. This much larger percentage reflects Spain's very different geographic location as part of Europe and as a member of the European Union, which results in greater interdependencies.

As the results in Figure 1 show, if Ibero-American universities are to expand their visibility in the international market and enhance international collaborations, they must offer more website content in English.

I also analyzed the websites of the 100 top-ranked and most prestigious universities in the Ibero-American region according to Webometrics. Of those 100 websites, 26 included content in English. Table 1 shows the sections and percentage of institutions that publish some English-language content, sorted by the highest percentage.

Table 1. Top Ibero-American university websites and their English-language content

|

Website section |

Percentage |

|---|---|

|

General: An overview of the country, the university, and the university's academic offerings and admissions process. |

100% |

|

Academics: Information on undergraduate and graduate courses, courses taught in English, courses taught only in Spanish, study abroad programs, and OpenCourseWare. |

92% |

|

About: A welcome from the president; a general description of the university, including key facts and its history, mission, and goals; the university's place in the wider world; and campus information, recent news, and testimonials. |

92% |

|

Faculty/schools: A list of schools and faculty coordinators, including contact information. |

81% |

|

Research/transfer: Information about the university's research impact, innovation, and consultancy; research centers and institutes; research groups; strategic areas; international collaboration and research projects; knowledge transfer; and research opportunities. |

69% |

|

University life/surrounding community: Getting to the university, living in the area, campus life, academic experiences, sports, cultural diffusion, FAQs, heritage, housing and dining, and maps, directions, and information on public transportation. |

62% |

|

Support services: Information about libraries and museums, orientation and educational services, medical services, employment opportunities, and social services. |

58% |

|

International credit mobility and international agreements: Bilateral agreements with universities in the European Commission's Life Long Learning Program–Erasmus [https://www.welcomeurope.com/european-funds/llp-erasmus-609+509.html#tab=onglet_details]; agreements with other Ibero-American universities; cooperation with US, Australian, and Canadian universities; various international networks and groups; and opportunities for student, staff, and faculty mobility. |

58% |

|

Research centers and institutes |

46% |

|

International resources: International student guide, university guide, impact and dissemination, welcome videos on YouTube, and photo galleries. |

23% |

|

Identity: Elements that define the university as a community and offer a sense of belonging including the logo; the motto (slogan); the school anthem and cheer; the university colors; and the sports anthem, logo, and organization. |

19% |

Best Practices for Internationalizing Websites

Based on my study of academic papers, blogs, and websites, I've assembled a list of five best practices for institutional websites aiming to expand their international presence.

1. Offer Key Features and Functionality

To increase their effectiveness, Angela Taylor12 recommends that websites offer users the following features and functionality:

- Optimized search engine

- Compatibility with all major browsers

- Attractive visual design that communicates brand values

- Easy/intuitive navigation

- Enticements to thoroughly explore and revisit the site

- Fast download

- 24/7 availability

- Interactivity

- Up-to-date content

- Accessibility on mobile devices

2. Focus on User Experience

Nielsen Norman Group provides insightful guidelines13 for institutions that want to guarantee a positive user experience on their websites:

- Clearly identify the university on every page

- Use images that reflect the university's values and priorities

- Make the "About Us" section count

- Emphasize strengths and achievements

- Make it easy for users to view a list of academic majors and programs

- Provide information about job placement after graduation (such as through a link from the website's alumni section)

- Clearly show application deadlines and offer a step-by-step description of the application process

- Follow the user journey by checking the main tasks for each type of visitor

- Beware the perils of making the website "cool"

- Be prepared for users to search for information about the university on external sites

3. Ensure Accessibility

The University of Pennsylvania's website [https://www.upenn.edu/about/styleguide-best-practice] offers tips to ensure that websites meet the Web Content Accessibility guidelines (WCAG 2.0):

- Keep navigation consistent throughout the site; users should always be able to return easily to the homepage and other major navigation points

- Divide information into clearly defined sections

- Use a logical naming convention for page headers, menu labels, and web addresses

- Ensure that all images include an ALT tag and height and width information to indicate the presence and nature of visual content for nonvisual users with screen reader software

- Provide contact information for site owners

- For links, use descriptive text — rather than simply "click here" — that makes sense when it is read out of context

- Understand and capitalize on the importance of search usability and search engine optimization

4. Use Professional Translators

If your institution decides to offer website content in a different language, it is important to have it professionally translated by a native speaker as the international higher education community is an educated audience.

Also, while English is the common language for international collaboration, institutions might also want to offer website content in other languages — such as French, Chinese, Portuguese, and German — depending on their location and target audiences.

5. Focus on Key Content Sections

Finally, you should ensure that your website offers five key sections in English (and possibly other languages) for international audiences: About, Studying at the University, Research/Transfer, Support Services, and University Life/Area. Table 2 shows the standard recommended content for each of these sections.

Table 2. Recommended English-language website content

|

Website section |

Content |

|---|---|

|

About |

|

|

Studying at the University |

|

|

Research/Transfer |

|

|

Support Services |

|

|

University Life/Area |

|

Seizing Global Opportunities

Because a website reflects an institution's identity and is often the first point of contact for prospective students, faculty, and researchers, universities should view their website as a tool for selling the institution and its values, and design its content and features accordingly.

Having the right content, language, user experience, accessibility, and effectiveness for an international audience is especially important now, as internationalization is an integral part of higher education's continuous change process. As such, it offers powerful opportunities for expanding an institution's global reach and reputation.

Notes

- Philip G. Altbach and Jane Knight, "The Internationalization of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities," Journal of Studies in International Education, Vol. 11, No. 3-4, 2007: 290–305. ↩

- Nelly P. Stromquist, "Internationalization as a Response to Globalization: Radical Shifts in University Environments," Higher Education, Vol. 53, No. 1, 2007: 81–105. ↩

- Adrian Curaij, Liviu Matei, Remus Pricopie, Jamil Salmi, and Peter Scott, eds., The European Higher Education Area — Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies, Springer, 2015. ↩

- Eva Egron-Polak and Ross Judson, Internationalization of Higher Education: Growing Expectations, Fundamental Values, IAU 4th Global Survey, 2014. ↩

- James Pick, Avijit Sarkar, and Elizabeth Parrish, "Internet Use and Online Activities in U.S. States: Geographic Disparities and Socio-economic Influences," Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2018: 3853–3863. ↩

- "The Importance of a Website," blog, College of Arts & Sciences, University of Kentucky. ↩

- Layla Hasan, "Using University Ranking Systems to Predict Usability of University Websites," [http://www.jistem.fea.usp.br/index.php/jistem/article/view/10.4301%2FS1807-17752013000200003] Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2014: 235–250. ↩

- Kurt Schimmel, Darlene Motley, Stanko Racic, Gayle Marco, and Mark Eschenfelder, "The Importance of University Web Pages in Selecting a Higher Education Institution," Research in Higher Education Journal, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2010: 1–16. ↩

- Gyorgy Losonczi, "Competitive Website Evaluation in Higher Education," Proceedings of FIKUSZ, 2012: 147–160. ↩

- Simon Marginson and Marijk van der Wende, "To Rank or to Be Ranked: The Impact of Global Rankings in Higher Education," Journal of Studies in International Education, Vol. 11, No. 3-4, 2007: 306–329. ↩

- Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, "Decalogue of Good Practices in Institutional Web Positioning." ↩

- Angela Taylor, "Good Website Design — Not Just a Pretty Face," In Practice, Vol. 33, No. 9, 2011: 486–489. ↩

- Katie Sherwin, "University Websites: Top 10 Design Guidelines," Nielsen Norman Group, April 24, 2016. ↩

Gabriela Gerón-Piñón is an Associate Researcher at Universidad de Monterrey and Founder and President of Connecting Iberoamerica.

© 2018 Gabriela Gerón-Piñón. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 International License.