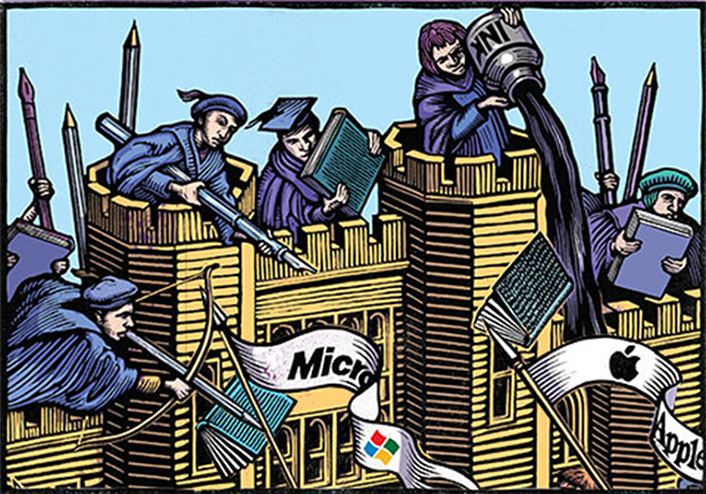

Since the advent of computing, higher education's IT chiefs have undergone many wardrobe changes. The shifts—from tinkerers to code talkers to enterprise architects—now require another wardrobe change. Can we energize our institutions' capacity to socialize the next wave of information technology in ways that fulfill technology's promise while respecting our institutions’ culture and legacy?

The emperor is in his dressing room.

As a young graduate student in history in the late 1970s, I was deeply influenced by David Landes's 1969 book Unbound Prometheus, a history of technological and social change during the Industrial Revolution.1 Landes's framework describing the interplay of functional need, technological innovation, and behavioral response has shaped my outlook over the ensuing 40 years.

As an IT professional, I have watched this interplay repeat itself as waves of new technologies arrived on campus. Each new wave seemed to carry with it an obligation for technology leaders and practitioners to reinvent their wardrobes, if not themselves. Every new wave signaled a shift in the required skill set and outlook of those who lead the organization and deployment of information technology.

We can metaphorically imagine the white lab coat–clad mathematicians and engineers who dominated the landscape from the mid-1940s through much of the 1970s. Thin ties, pocket protectors, horn-rimmed glasses, and Hush Puppies helped define the software engineer of the 1970s. The broad introduction of personal computing in August 1981, the spread and interconnection of networks, and the deployment, by the mid-1990s, of HTML, URI, and HTTP brought computation and communication to the office and, increasingly, to the home. The simplification and standardization of web search by Google created the preconditions for a revolution in work, commerce, and everyday life. Wardrobes became nearly as diverse as IT professionals. Larry Ellison, it was noted, wore Armani while Steve Jobs will be remembered for wearing blue jeans and his signature black turtleneck. As the titans of technology conquered each challenge of the OSI's 7-layer model,2 information technologies moved from the glass house of enterprise mainframes to everyone's house. The release of the iPhone in 2007 placed computational power and ubiquitous connectivity in everyone's pocket.

Every challenge posed in the OSI model was met with a technological innovation. Every innovation, in turn, begat widespread social and behavioral responses—some intended, some unintended. Clayton Christensen and others introduced language and analysis around the notion of disruption—the modern phraseology for this matrix of social and behavioral response.3 As software applications—like spreadsheets—became refined, entire professions were recast. As search and presentation technologies matured, great libraries became accessible over networks. As worldwide networks were connected and as English became the world's unofficial language of business, international-scale collaboration became widespread. And as connectivity became truly universal and mobile, core aspects of how we live, learn, interact, work, and do business have shifted.

Wardrobe Changes

While computation and communication continue to have deep and demanding technical challenges, the roles of the IT leader and organization have evolved. This is particularly true in higher education. Outside of computer science departments, IT leaders are no longer the "tinkerers-in-chief"—the inventors of new technologies. As they move their locus of operations increasingly to the cloud, IT leaders also rely less on their engineering sophistication. In broad terms, IT leaders have moved from making things, to running things, to socializing things. As leaders position themselves to play leading roles in socializing technology-enabled change, the question of wardrobe arises again. What are the clothes—that is, the skills—that tomorrow's IT leaders will need? Are the challenges of socialization so vastly different that yesterday's IT leaders will in fact have no clothes to suit? Is the IT leadership cadre ripe for a total makeover, or—like Google, Facebook, and others—will we need to find ways for technologists, marketeers, and increasingly, ethicists to share a clothes rack? Will IT leaders be accountable for technology's socialization, or will provosts, deans, business officers, and others play decisive roles?

According to writers for Forbes, the New York Times, and McKinsey & Company, among others, today we are all living in the Age of Big Data.4 IDC predicts that by 2025, the world will create and replicate 163 zettabytes (163 trillions of gigabytes) of data annually. This represents a tenfold increase over the annual amount of data generated in 2016.5 The social and behavioral landscape associated with the technologies defining the Age of Big Data will demand a radically new set of skills among IT leaders and in the IT organization of the future (see table 1).

Table 1. Challenge and Response: Prometheus Today

|

Challenge |

Response |

Disruption |

Skills Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Prediction and Personalization |

Analytics Big Data Management Cloud Computing and Storage High-Performance Networks Adaptive Courseware |

Changed capacity to manage institutional, organizational, and individual performance and learning outcomes |

Ethical leadership Capacity to shape and instantiate a service philosophy Institutional strategy Ecosystem management Data management |

|

Rapid Prototyping |

3-D Printing |

Changing economics of design and manufacturing Consumerization of "making" |

Management of IT security Oversight and governance of institutional connectivity standards |

|

Remote Control Supply Chain Management |

Internet of Everything |

Most human activity now assuming connectivity between people and smart "things" |

5-G and beyond mobile network architectures Identification, tracking, authentication, and authorization of "things" |

|

Human-Machine Interaction |

Artificial Intelligence Natural Language Processing Robotics Augmented Reality Virtual Reality |

Widespread changes to significant aspects of institutional work and program and service delivery |

Legal and ethical leadership (community standards, disclosures …) Governance of IT Change management User awareness building Ecosystem management |

|

Nurturing Communities |

Social Networks Governance Codes of Conduct Filtering, Screening, and Vetting Capabilities |

Alignment of institutional information resources and practices with the institution's beliefs and policies about truth, academic integrity, diversity of ideas, intellectual "safety," etc. |

Legal and ethical leadership Promotion of information literacy Establishment and enforcement of community standards |

|

Community and Asset Protection |

IT Security Infrastructure Surveillance Technology

|

Reconciliation of community safety and security with privacy rights, openness of infrastructure, and information resources |

Legal and ethical leadership Deep listening Data management, including responsibility for record retention, access control, and preservation |

While the entries on this list of possible priority challenges could be argued, clearly these challenges—and others that could replace them—bear little resemblance to the OSI's 7-layer challenge model of the 1970s. While the engineering and technical challenges of information technology will never go away, they are increasingly tucked in the realm of making things faster, more reliable, cheaper, and easier to use. Moreover, while many technical responsibilities are becoming more focused on incremental improvement, many are also migrating to corporate research and development organizations and to cloud providers who are leveraging nearly unimaginable scale economics and security capabilities.

When the Anchor of Truth Disappears; or, Seeking Questions Hidden by Answers

Remarkable people have opined on the nature and purpose of the university. Thomas Jefferson argued that universities exist to form "the statesmen, legislators and judges, on whom public prosperity and individual happiness are so much to depend." William Harper, the founding president of the University of Chicago, stated that the mission of the modern university is to "maintain for democracy the unity so essential for its [democracy's] success." Thought leadership, the search for truth, and Woodrow Wilson's spirit of service are the pillars that have both supported modern higher education and imbued the university enterprise with special standing in local, regional, national, and global life.6

We should recall that the search for truth both drives academic inquiry and underpins its skepticism. It spans the disciplines. The mathematician Blaise Pascal advised, "Nothing gives rest but the sincere search for truth." B. H. Liddell Hart agreed: "The search for truth for truth's sake is the mark of the historian." Linus Pauling described science as "the search for truth," while Alwar Balasubramaniam identified artists as "the root of a tree. They can search for truth or reality in their own way." This search for truth is the glue that holds the disparate elements of academic inquiry together and is the basis of mutual comprehension, purpose, and respect across diverse academic disciplines.7

If the university is a servant of the truth, a beacon of the truth, a sanctuary of truth seekers, and an enabler of future generations of truth seekers, what will happen if the anchor of truth disappears? More specifically for us, what is the role of information technology and of IT leaders in protecting, preserving, or even extending what the theologian Cardinal John Henry Newman described as the university's role in teaching students "to think and to reason and to compare and to discriminate and to analyse"—that is, to separate the true from the "fake"?8

There can be little doubt that truth is under assault or that the pace of this assault is being conditioned (or constrained) by information technologies. As the professor and philosopher Marshall McLuhan warned: "The more the data banks record about each one of us, the less we exist." His friend John Culkin reminded us: "We shape our tools and thereafter they shape us." As we have moved from McLuhan's typographical age deeply into the electric/electronic age, more and more of his concerns and predictions have shaped our environment.9

McLuhan was never more correct than when he cautioned: "A point of view can be a dangerous luxury when substituted for insight and understanding."10 Modern 7x24 newscasting became the canary-in-the-coal-mine social response to challenges overcome by a variety of technologies. The former Fox News host Bill O'Reilly inspired Stephen Colbert's "truthiness" punditry, which was based on the belief or assertion that a particular statement is true based on one's intuition or perceptions without regard to evidence, logic, intellectual examination, or facts. The New York Times columnist Farhad Manjoo, in his 2008 book True Enough: Learning to Live in a Post-Fact Society, opined that many of us have begun to organize ourselves into echo chambers that harbor diametrically different facts—not merely opinions—from those of the larger culture. Modern social networks put an ominous accent on McLuhan's warnings about the dangerous side of individual viewpoints. Bogus virality on social media enabled the reputation-damaging Pizzagate scandal and the Russian planting of divisive posts on Facebook in 2016. In the summer of 2018, more than 20 people were lynched by mobs in India as a result of child-abduction rumors spread via WhatsApp. In July the social media app was modified to reduce the pace of forwarding messages. Online mobbing and storming have also led directly to the editorial repudiation or scrubbing of articles in the Business Insider and The Nation. In July 2018 the actress Scarlett Johannsson "respectfully withdrew" from a controversial film project in the wake of a forceful Twitter storm.

IT leaders—for a time—flew below the radar on issues like these. While they led institutional efforts to acculturate incoming students to net citizenship, shaped network bandwidth, opened or closed ports, and filtered content from dubious sources, IT leaders preferred to think of themselves as network providers. Such providers, they reasoned, bear little responsibility for the content or community behaviors that travels across the institutional networks. But as we have all witnessed with the recent market drubbing of Facebook, providers of social networks are now at the center of debates about the ethical and appropriate management and uses of information technologies and content. Though IT leaders do not want to become the thought police for higher education, they can no longer remain outside these policy debates.

The pitch of these debates will rise as so-called third-wave technologies find their way into broad adoption. Increasing use of video surveillance and progress on facial recognition will surely both improve campus security and raise issues about privacy, free speech, and the limits of in loco parentis monitoring. One wonders how the free speech movement might have played out under the watchful eyes of modern surveillance. Smart buildings and embedded sensors will log the paths of students, faculty members, and staff on campus, leaving a record of their collegiate experiences. Adaptive learning tools are showing dramatic learning results at Georgia State University, the University of Central Florida, and elsewhere, but they depend on large datasets of student work and raise privacy concerns. And while adaptive courseware can unearth students' behavior patterns and nudge students toward effective learning strategies, many educators worry that the increasing reliance on algorithms and automated responses will promote formulaic or even rote approaches to learning.

Ivory Tower or Tower of Babel?

In the end, the outcome of the debates about how, whether, and when any specific institution is to socialize emerging information technologies may be less consequential than the debates themselves. In many ways IT leaders have seen how the networks they have engineered and operated have become higher education's public square. For many of today's public speakers, mobile devices and networks have replaced makeshift podiums and megaphones. Tech-savvy opinion shapers can now project information (or disinformation) across campus or across neighborhoods, cities, states, and nations, tilting opinions (or voting patterns) or inspiring and choreographing spontaneous mobs.

Technology tools have the capacity—as Bill Gates warned—to create filter bubbles. Technology such as social media "lets you go off with like-minded people, so you're not mixing and sharing and understanding other points of view. . . . It's super important. It's turned out to be more of a problem than I, or many others, would have expected."11 Filter bubbles make it possible for technology users to become separated from information that disconfirms, and from people who disagree with, their viewpoints. Our technologies and the bubbles they enable risk isolating us culturally and ideologically. Isolation and the echo-chamber effect, in turn, can lead to tribalism. Intellectual isolation and tribalism—while sprinkled throughout the history of higher education—are antithetical to nearly every conception of the university and erode the capacity of those in higher education to uncover truths. When combined with uneven student information literacy and abundant fake information, intellectual isolation and tribalism splinter our institutional communities, stoking—rather than extinguishing—the fires of intolerance that seem to plague modern society. It is a sign of the times that John Ellison, dean of the College at the University of Chicago, felt obliged to remind the entering class of 2016: "We expect members of our community to be engaged in rigorous debate, discussion, and even disagreement. At times this may challenge you and even cause discomfort."12

As higher education embeds artificial intelligence (AI) or installs intelligent speakers throughout its dormitory rooms or injects other technologies into student prospecting, loan counseling, crisis hotlines, and classrooms, commonplace objects and processes will take on increasingly "black box" aspects. In some respects, institutional processes—including teaching—will become like autonomous vehicles. The processes will get most people where they're going, but few people will understand how they got there. Between now and then—and certainly when objects and processes fail— issues will surface, opinions (informed and otherwise) will proliferate, and tempers will flare. Emerging technologies raise grave issues, carry significant risks, and beg consequential choices. Recently, more than 1,400 Google employees signed an internal petition decrying the company's secret efforts to censor a fact-limiting browser being readied for use in China. A similar protest prompted the company to cease defense-related contracts with the U.S. Department of Defense. AI "bug hunters" at DeepMind Technologies are chronicling myriad examples of algorithms that are doing what their builders said but not what they wanted. Such algorithms take shortcuts that their creators had not thought to define as off-limits. As Tom Simonite put it in Wired: "Teach a learning algorithm to fish, and it might just drain the lake. . . . If a neural network managing an electric grid were told to save energy . . . it could cause a blackout."13

How any specific institution will approach socializing these new and fraught technologies—amid possible pitchforks and torches carried by the academy's righteous and fearful—may depend on the CIO. The CIO has always kept an eye on the possible: on the vision of how information technologies can enable or even transform core institutional activities. Even more, the CIO can create or support an institution's capacity to see inside the black box. And most important, the future CIO must become the great communicator—not only of the capabilities and workings of new black boxes but also of the strengths and shortcomings of these technologies in the social and political context of the institution.

To succeed, this future CIO must

- be deeply attuned to institutional history, mission, and culture;

- employ a governance that informs and confers credibility on CIO actions that increasingly brush against the soul of the institution;

- be a keen listener;

- have the ability to communicate complex technical ideas and concepts in ways that lend compelling meaning to the institution's social and political context;

- connect what is technologically possible to the student experience, the institutional outcomes, and the vitality of the institutional community; and

- ensure fidelity to higher education's first principles—that truth seeking is mission-critical and that divided houses fall.

The CIO's new clothes are not wholly new. Even as those of us who still cherish or even wear Hush Puppies make for the profession's exits, we are being succeeded by professionals who are attuned to their institution's heartbeat and who possess many of the skills outlined above. Likely, ethics is the CIO's next sartorial frontier. Forty years ago, when Reed College CIO Marty Ringle taught a course on the ethics of technology, he went to great lengths to emphasize that the thrill of inventing new technologies needed to be tempered by an understanding of how those technologies might alter society and impact individuals." Today, Ringle warns: "The need to be mindful of the ethical implications of what we do—especially in education—is greater than ever." Former CIO Susan Metros agrees: "As IT professionals, we need to provide services and invent tools that will help students sort through the moral and ethical issues of seeing while questioning whether to believe."14

So much more can be—and will be—written about how the technologies shaping the Age of Big Data are, in turn, shaping us. As we read about the unfolding of events such as Facebook's privacy debacle, or the censoring of search by Google in China and elsewhere, or the Russian tampering with U.S. and other elections, or the rise of cybermobs or cyberbullies or filter bubbles, it is easy to become dispirited or downright dystopian in outlook. AI is highlighted here because, in part, it is such an easy target for those of us who have borne witness to a few of the unintended consequences of information technology over the years. As with automobiles, information technologies are becoming more powerful and more reliable. And as with automobiles, information technologies are becoming sealed systems. Their internals can be understood only by the certified high priests or priestesses of IT. It is also becoming less obvious who is in control of the human/technology interface at any given moment. Is your car driving, or are you? Is that a TA you are texting, or is it a teaching bot? It is likely that just as the "e" is dropping from e-commerce or e-learning, the word artificial will drop as we discuss intelligence. At some point, we are simply unlikely to know or understand the sources of our own knowledge.

The things we cannot see and do not understand often frighten us the most, especially when potent technologists—such as Bill Joy—warn us that accelerating technological change could cause something like the extinction of human beings within two generations.15 IT leaders must evolve. They need another wardrobe upgrade. They must become those priests and priestesses who can see what's in the black box. They must understand how what they see inside the black box connects to not only the mission of their institutions but also their institutions' cultures, leading characters, aspirations, and communities. They need to mind and respect their institutions' ethical guard rails. And they need to become the great explainers whose credibility and standing can promote either caution or experimentation, when appropriate.

Maybe now is the time to ask professional organizations and philanthropic foundations to join forces to create a kind of Underwriter's Laboratory for educational technology. Maybe there is more to techno-skepticism or techno-evangelism than shouting across filter bubbles. Maybe we should not fully entrust the education of young people to the marketing hype of well-intentioned edupreneurs and edupunks. Maybe we can collectively organize the technical capacity to look "under the hood" of emerging technologies and verify (or not) that these technologies perform the functions represented by their creators in the marketing literature. With testing and certification as a foundation, maybe we can sharpen our current research agenda's focus on the keys to effective socialization of technologies. The potent combination of testing, certifying, and guiding the socialization of emerging technologists will surely help both the eager early adopter and the die-hard skeptic. In any case, more information cast in clear terms could both enable the communicator and lower the possibility of the debate's polarization. Situating such information in both ethical and cultural contexts is key. Paul LeBlanc, president of the University of Southern New Hampshire (SNHU), makes a compelling prediction: "We will need as many ethicists and sociologists at EDUCAUSE gatherings as IT staff and edtech vendors."16

With machine learning ahead of us, the pace of technological change is about to quicken. It is not likely than any of us will be able to keep up. If we lose the capacity to deeply influence the adoption and socialization of technologies at our higher education institutions, we risk becoming just another opinion echoing inside another filter bubble. The stakes are high. As Ringle said: "Let's not screw it up."

Notes

- David S. Landes, The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present, 1972 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969). ↩

- See Vangie Beal, "The 7 Layers of the OSI Model," Webopedia, April 3, 2018. ↩

- Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997); Clayton M. Christensen, Michael B. Horn, and Curtis W. Johnson, Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008). ↩

- Brad Peters, "The Age of Big Data," Forbes, July 12, 2012; Steve Lohr, "The Age of Big Data," New York Times, February 11, 2012; Nicolaus Henke et al., "The Age of Analytics: Competing in a Data-Driven World," McKinsey Global Institute, December 2016. ↩

- David Reinsel, John Gantz, and John Rydning, "Data Age 2025: The Evolution of Data to Life-Critical" [https://www.seagate.com/www-content/our-story/trends/files/Seagate-WP-DataAge2025-March-2017.pdf], IDC white paper, April 2017, p. 3. ↩

- Thomas Jefferson, "Report of the Commissioners for the University of Virginia, 1818" [https://www.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/92uva/92facts3.htm], quoted in National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Thomas Jefferson's Plan for the University of Virginia: Lessons from the Lawn, n.d. [accessed September 3, 2018]; William Harper, "The University and Democracy," The Cosmopolitan 26 (November 1898–April 1899), p. 686; Woodrow Wilson highlighted the spirit of service in speeches delivered on the occasion of Princeton University's 150th anniversary and at his inauguration as Princeton's president in 1902 (see, for example, "Our History," Woodrow Wilson School of Public & International Affairs website). ↩

- Blaise Pascal, Thoughts, trans. W. F. Trotter, The Harvard Classics, vol. 48, pt. 1 (New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1909–1914); B. H. Liddell Hart, Why Don't We Learn from History? (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1944); Pauling quoted in "Linus Pauling Biography," Linus Pauling Institute website; Balasubramaniam quoted in Elizabeth Kuruvilla, "Alwar Balasubramaniam: The Reclusive Superstar," LiveMint, January 17, 2015. ↩

- Newman quoted in Sophia Deboick, "Newman Suggests a University's 'Soul' Lies in the Mark It Leaves on Students," The Guardian, October 20, 2010. ↩

- Marshall McLuhan, with Wilfred Watson, From Cliché to Archetype (New York: Viking Press, 1970), 13; John M. Culkin, "A Schoolman's Guide to Marshall McLuhan," The Saturday Review, March 18, 1967), 70; Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962). ↩

- McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy, 216. ↩

- Kevin J. Delaney, "Filter Bubbles Are a Serious Problem with News, Says Bill Gates," Quartz, February 21, 2017. ↩

- John (Jay) Ellison, "Dear Class of 2020 Student" (letter to the University of Chicago undergraduate student body), n.d. ↩

- Tom Simonite, "When Bots Teach Themselves to Cheat," Wired, August 8, 2018. ↩

- Quoted in "Twenty Years: EDUCAUSE and Higher Education IT," EDUCAUSE Review 53, no. 4 (July/August 2018). ↩

- Bill Joy, "Why the Future Doesn't Need Us," Wired, April 1, 2000. ↩

- Paul LeBlanc, "Reading Signals from the Future: EDUCAUSE in 2038," EDUCAUSE Review 53, no. 4 (July/August 2018). ↩

Richard N. Katz is President of Richard N. Katz & Associates.

© 2018 Richard N. Katz. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review 53, no. 6 (November/December 2018)