Key Takeaways

-

As the use of nontraditional learning management systems has increased in online courses, so too has the need to understand how students use and experience these systems.

-

A recent study of graduate student use of Google Classroom offers insights into nontraditional LMS use and its potential benefits and challenges.

-

The study also highlights ways to improve the effectiveness of nontraditional LMSs and increase students' interactions with each other and their instructors when using them, thereby helping build community within online courses.

Web applications such as Facebook and Twitter have been used in higher education for many years.1 As use of these tools has increased, they have come to function, in some ways, as nontraditional learning management systems (LMSs). For example, Krishna Bista noted that graduate students had a generally positive experience using Twitter for several activities, including developing professionally, sharing course information, and interacting with classmates and the professor.2 These activities, which typically take place in a traditional LMS, are now increasingly occurring on social media sites — that is, on de facto nontraditional LMSs.

Some companies have created nontraditional systems to mirror these more popular sites; consider, for example, the resemblance between Schoology and Facebook. Google has created its own nontraditional LMS in Google Classroom. Although it is quite popular and often discussed in the context of K–12 settings, very few studies address the use of Google Classroom in higher education. I sought to address this gap in the literature by examining graduate students' experiences with Google Classroom in fully online courses.

The Google Classroom Study

In addition to addressing the current gap in the literature related to the use of the nontraditional LMS Google Classroom in higher education, I chose to conduct a study on this nontraditional LMS because its use was unique to graduate education. While elements of the LMS were troublesome for graduate students, there were also aspects of Google Classroom that enhanced course interactivity.

My research question was: What are students' perspectives on using a nontraditional LMS? Even though the study deals specifically with Google Classroom, I chose to focus on the nontraditional LMS aspect of the tool in order to situate the work in a larger conversation about nontraditional LMSs and avoid the impression that the work is a review or tool critique, which it is not.

Basic Approach

I conducted a hermeneutic phenomenology3 and used the concept of connectivism4 as a framework. Hermeneutic phenomenology is an appropriate methodology for this particular project because it emphasizes the nuances of lived experience.

In planning the study, I sought participation from students who have used Google Classroom beyond just the students in my own courses. To obtain their perspectives on Google Classroom, I asked participants open-ended questions via a Qualtrics survey that I posted to their Google Classroom spaces with a note indicating that their participation was voluntary.

Although phenomenology "attempts to describe and interpret … meanings to a certain degree of depth and richness"5 and is often associated with in-depth interviews, I thought that the open-ended electronic survey might result in a larger response from students because it was easy to use and accessible for those who work full time while attending classes or who have schedules that make it difficult for them to participate in more traditional interviews. Also, the open-ended questions gave students space to share their perspectives on Google Classroom.

Participants and Data Collection

Because Google Classroom's use is still quite new in higher education, the pool of potential participants was not very large; a total of seven graduate students participated in the study. Because the responses were anonymized via Qualtrics, I did not know who the participants were and did not ask them to provide e-mail addresses or any other identifying information.

The questions were all open-ended, so participants had an opportunity to express their own ideas about impact, interaction, and overall experiences with Google Classroom. Also, because I teach courses using Google Classroom, I was able to triangulate data via my general observations of the Google Classroom area,6 even if I did not observe a particular participant's specific classroom space, as the Google Classroom layout is similar for all courses.

Findings

I was looking forward to receiving participants' feedback on their experiences with this nontraditional LMS because, as noted previously, Google Classroom is not widely used in higher education. The findings are divided into two sections based on participants' contributions: student-to-student interactions and student-to-professor interactions.

Student-to-Student Interactions

Six of the seven participants had not used Google Classroom prior to the courses they were enrolled in during this study. Participants reported mixed experiences with certain aspects of Google Classroom. For example, when asked how Google Classroom affected interactions with other students, Participant 1 noted minimal interaction with classmates, generally. Participant 2 did not indicate appreciable differences in interactions with other students and noted that other tools, such as Facebook Messenger and e-mail, facilitated the "most impactful" interactions with classmates.

Participant 4's situation was unique in that course participants had opportunities to interact with classmates in a face-to-face environment, despite it being an online course, and Participant 4 took advantage of those opportunities.

Other participants noted different experiences with student-to-student interactions. For example, Participant 6 spoke positively about being able to "follow what other students were doing in their assignments and learn from their perspectives" via Google Classroom. Participant 6 added, "We could view one another's work and provide comments or ask questions." Likewise, Participant 5 stated, "Google Classroom made it easier to interact with other students in the course … because on Google Classroom, the communication is upfront." Participants 5 and 6 both found Google Classroom to be very interactive, but other participants did not notice much difference in the interactions compared to traditional LMSs they had used such as Blackboard.

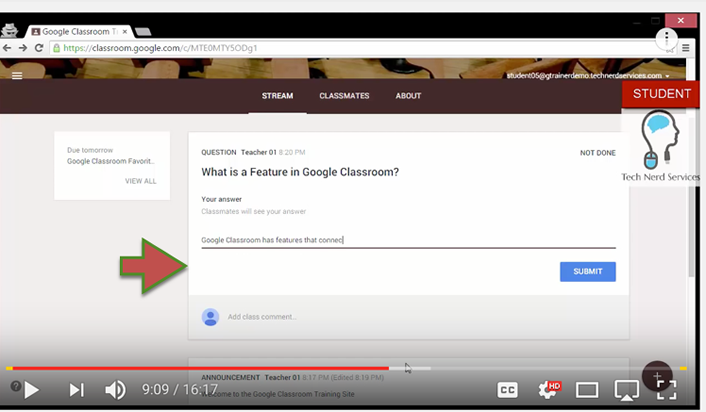

One of Google Classroom's major features is the course stream (see figure 1). Some of the study participants did not like this feature. For example, Participant 3 stated that interactions with other students in the course were "fairly straightforward," but continued, "… Google Classroom's 'course stream' was often confusing. I had a difficult time seeing when another student added something, said something, or made a comment on my posts. Not user friendly or engaging, I'm afraid." Participant 7 offered similar comments, stating, "I didn't like the stream, it was awkward and didn't feel natural to use."

Figure 1. The Google Classroom course stream

In contrast, Participants 5 and 6 had positive comments about the stream. For example, Participant 5 highlighted the "upfront" communication of Google Classroom and preferred it to the "discussion board" that other LMSs use. Participant 6 noted, "Communication via the stream was always encouraging between students." Although Participant 6's comment can also be viewed as commentary on the positive course climate, if the participant found the stream problematic, this would have been the logical juncture at which to mention it. Therefore, I surmised that Participant 6 had a positive perception of the course stream.

Student-to-Professor Interactions

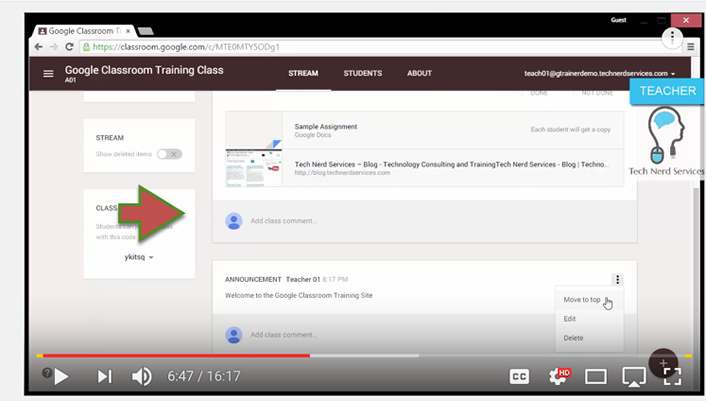

As for interactions with professors using Google Classroom, some participants found they were similar to interactions with professors in other LMSs. Participant 4 said, "It was neither better nor worse than Blackboard would have been." Participant 2 made similar comments: "Google Classroom didn't make an impact on my interaction with my professor, I would say the same level of interaction was available … on Blackboard." Participant 6 expressed a different perspective (see figure 2):

"Because it was an online course, I had no in-person interactions with the professor. If I needed, I could create or engage in dialogue with the professor on the classroom stream. I could also communicate details of the assignment with the professor…"

Figure 2. Students can post comments in the course materials section.

Finally, Participant 7 said the Google Classroom course stream "was okay — it seemed more natural than with other platforms I've used."

In addition to the course stream, part of what made courses so interactive for students who highlighted student-to-student and student-to-professor interactions was the Google Docs function. On all submitted assignments, students could add comments to each other (via document invitation only) and to the professor, and also respond to the professor's comments. Thus, in addition to communicating on the course stream, students could communicate and collaborate via Google Docs. Although Google Docs is available to people who are not using Google Classroom, it is automatically included with Google Classroom.

Recommendations

The current study, although small, provides helpful suggestions and considerations for using Google Classroom and other nontraditional LMSs in higher education.

Nontraditional LMSs such as Google Classroom are new to some students in higher education, so tutorials can be helpful. Several students in my study mentioned discomfort with the course stream. Given this, it would be beneficial to use a tag via Google Classroom's "Topics" section and post the Google Classroom tutorial to the Google Classroom space. For example, my institution provides access to Lynda.com accounts, so I found a Google Classroom tutorial on Lynda.com and shared it with my students via e-mail.

Tags can also be helpful for organizing course data if the course stream begins to get crowded, which can occur in large courses or courses with lots of material. Those teaching large courses will need to keep this in mind. Although some students may not be bothered by a full course stream (as was true of some participants in my study), tags also provide a way to keep course information organized. For example, I created an "Assignments" tag so that students could go directly to their assignments without searching the course stream. I also created a "Course Trailer" tag that directed students to the trailer I made for the course — just as a reminder of some of the concepts we would cover in the course and perhaps for a bit of fun as well. I enjoyed making a trailer for each course, and some of the students in my courses remarked that they enjoyed seeing the trailers.

Students can also benefit from Google Classroom's interactive components, particularly if they have no face-to-face access to the instructor and other students. In my study, for example, Participant 6 did not have a face-to-face option, but still felt connected to classmates and the professor because of the interactive opportunities in the classroom space. Among those opportunities are posting comments under stream-uploaded information and on assignments that are submitted through Google Docs. Students can also upload videos and photos to the course stream to interact in non-text-based ways. Currently, however, students cannot post non-text contributions in the comments section under assignments.

In addition to providing opportunities to interact, encouraging students to take advantage of those opportunities and post comments and questions when using Google Classroom or other nontraditional LMSs is also important. Such interactive moments can be meaningful and help build community within the course, as well as help improve experiences with group assignments or other collaborative elements of the class. For example, when a student in one of my courses had a question about an assignment, another student was able to provide a response via the course stream. Students in my courses also seemed to enjoy the introduction assignments where they could comment on each other's text and photo contributions. These interactions proved helpful, as students had pair and group work later in the classes. By interacting early on in the courses, students had the opportunity to get to know each other and establish connections.

Conclusion

Overall, the graduate students in my study seemed to have a positive experience with Google Classroom. When asked if they would use Google Classroom again, five of the seven participants said, "yes." I would consider using Google Classroom again as well, but only for a small course. Knowing that the stream can be a bit daunting for some students gives me pause about relying on it for larger classes. With smaller courses, the stream is much more manageable. My students and I were able to have meaningful discussions about their work via Google Docs, and although study participants did not mention Google Docs specifically, I would still encourage students to interact with my comments so that we can continue a dialogue regarding their work. I would also encourage them to use Google Docs for peer review assignments in the course. Although Google Classroom has its challenges, aspects of the nontraditional LMS enhanced interactions in online courses.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Associate Provost for eLearning (APeL) Office and the School of Education Technology Integration Center at William & Mary.

Notes

- Casimir C. Barczyk and Doris G. Duncan, "Facebook in Higher Education Courses: An Analysis of Students' Attitudes, Community of Practice, and Classroom Community," International Business and Management, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2013: 1–11; and George Veletsianos and Royce Kimmons, "Scholars in an Increasingly Open and Digital World: How Do Education Professors and Students Use Twitter?" Internet and Higher Education, Vol. 30, 2016: 1–10.

- Krishna Bista "Is Twitter an Effective Pedagogical Tool in Higher Education? Perspectives of Education Graduate Students," Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2015: 83–102.

- Max van Manen, Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy, State University of New York Press, 1990.

- George Siemens, "Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age," [http://www.itdl.org/journal/jan_05/article01.htm] International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, January 2005.

- van Manen, Researching Lived Experience, 11.

- John W. Creswell and Dana L. Miller, "Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry," Theory into Practice, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2000: 124–130.

- Tech Nerd Services, “Tutorial: A Guide to Google Classroom,” 2015.

- Ibid.

Stephanie J. Blackmon, PhD, is an assistant professor of higher education in the School of Education at William & Mary.

© 2017 Stephanie J. Blackmon. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.