Key Takeaways

- Students expect the higher education institutions they attend to provide appropriate learning and technology support, along with security and privacy for the personal information they share with the institution.

- Given the many reported system/data breaches, colleges and universities could clearly do a better job of protecting the student, faculty, and staff information entrusted to them.

- The college or university should have a CIO who is a member of the leadership team, reports directly to the university president, and is empowered, authorized, and supported to exercise the appropriate technical judgment to benefit the institution.

It seems that almost weekly we hear of amazing technology breakthroughs and innovations that leave little doubt we truly live in the knowledge age. In this new era, businesses and organizations operate in a global information technology economy and environment thanks to the level of technology employed. Because knowledge and ideas have become an increasing source of economic growth, education and IT are increasingly pertinent to an individual's success. Many people attend colleges and universities to increase their knowledge and competencies, which helps them become better qualified to take advantage of the employment opportunities available. In doing so, they expect the higher education institutions they attend to provide appropriate learning and technology support, along with security and privacy for the personal information they share with the institution. Given the many reported system/data breaches, colleges and universities could clearly do a better job of protecting the student, faculty, and staff information entrusted to them.

Vulnerabilities of IT in Higher Ed

Similar to many businesses, colleges and universities participate globally in this new economy via their IT infrastructure connectivity to the Internet — which makes them equally vulnerable to information security breaches.

Due to the frequency of security breaches in higher education systems, we can easily become anesthetized to them. The various security reports regarding the rise of data breaches in higher ed foretell a potentially systemic challenge that must be addressed aggressively. Although many industries suffer similar breaches, colleges and universities must address the problem to maintain their integrity. They must apply more than just the latest technology to defend the university's data and information systems if they are to adequately protect the information and data entrusted to them.

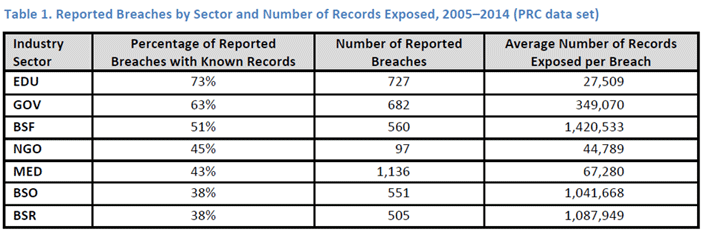

The past few years have seen a steady increase in system breaches of various organizations connected to the Internet. Although this by itself is alarming, we are also seeing that within these breaches has been a rise in the level of data/records compromised. For colleges and universities, however, this issue holds particular importance because the amount of higher education systems breached have increased in the past few years. Just in Time Research: Data Breaches in Higher Education reported that from 2005 to 2013, colleges and universities made 551 breach reports — a rate of just over one per week. The largest proportion of the reported breaches fell into the hacking/malware classification (36 percent). Based on the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse (PRC) data, education (K–20) as an industry has the second largest number of reported breaches (727), and 73 percent of breaches attributed to the education sector included data about the number of records exposed per breach. See table 1.1

© 2014 ECAR. Used with permission.

According to the Identity Theft Resource Center's (ITRC) January 2016 report, the number of U.S. data breaches tracked in 2015 totaled 781, which represents the second highest year on record since the ITRC began tracking breaches in 2005. Of the various sectors breached, ITRC explained that the education sector ranked fifth with 7.4 percent.

Based on the magnitude of recent university data breaches, one can only question whether institutions have lost sight of the importance of the information contained in their systems, or if they understand the value of such vast amounts of data in the wrong hands. Such information as thousands of records of personally identifiable information (PII), which might include data such as names, dates of birth, Social Security numbers, addresses, and phone numbers of students, faculty, and staff members, are not important just to the owners — hackers also consider this key data that is easy to obtain.

Such information is so easy to obtain that

throughout the civilian [IT] arena, there are active, open source discussions about how to penetrate computer networks, and sophisticated penetration tools are available to anyone with Internet access. Many of the sites generated by the [search] term 'computer hacking' display and teach specific tools for mischievous or malevolent activity. These malevolent sites run the gamut from 'point and click' procedures that can be used by anyone with a computer mouse to powerful tools for experienced hackers. From the hacker's perspective, the information is already available, and thousands of users already know how to attack networks.2

While much discussion about the importance of security takes place within the hallowed halls of higher education, lots of it centers around the latest technology. This is unfortunate because it negates the focus on the appropriate internal actions required to better defend higher education information systems from data breaches. It might therefore give those with nefarious objectives the opportunity to further exploit systems.

Since technology alone is not the answer, institutions must take a deeper look at what is contributing to the security challenges in higher ed. These challenges appear, for the most part, to be predicated on operational and systemically related issues pertaining to how colleges and universities operate. Due to operating distinctions, institutions of higher education have six specific challenges to overcome that might be hindering their ability to better secure the enterprise and defend against electronic data breaches:

- Experienced CIO

- CIO reporting line

- Institutional silos of technology

- Talented technical IT staff

- Formal information assurance/security department

- Appropriate information assurance framework

Experienced CIO

Public and private industry and institutions in general have embraced the strategic benefits of IT to facilitate organizational success. However, within the confines of higher education, it is not uncommon to find colleges and universities that still do not have a formal CIO role, and for some that do, CIO is merely a title lacking the authority, legitimacy, and latitude to function appropriately. The importance of having an experienced CIO requires more than having an individual in the position with little real-world executive experience. At many institutions where a CIO exists in principle, in practice this person simply runs the institution's technical operations from a basement-like facility. IT is treated as a necessary evil; the IT staff's voices and ideas are seldom heard. Rarely, they are summoned and their opinions sought to help senior leadership reach a conclusion on a specific matter. In many of these cases, unfortunately, other than asking for information, the leadership does not adequately consult, treat, or understand the CIO as the person best able to strategically infuse technology to accomplish business objectives. These institutions do not see IT as a core enabler of their success. Not having a CIO as the senior leader charged with protecting the institution's data and information can also mean the oversight of and day-to-day responsibility for information assurance and information security does not adequately fall under the purview of senior leadership until a security breach occurs.

In his 2015 article "5 Reasons the CIO Matters More Than Ever," Thornton May explained that

the world has gone digital. Companies rise and fall on the quality of their information technology. The CIO plays a critical role as he or she creates a competitive business advantage with that technology, leads the company effectively into the digital space, coordinates the multiple parts of the business that connect through the Internet, engages in strategic conversations with their peers, and oversees a digital environment that is growing exponentially year by year.3

In doing so, the CIO must understand the necessity of protecting all aspects of their institution's digital investment and data.

CIO Reporting Line

Additionally, if a CIO role exists, it is not uncommon for this position to have a reporting line to someone other than the university president. Colleges and universities that operate in this way do themselves a disservice!

"The CIO ought to be a part of the executive team given the incredible impact IT can and does have, and how intertwined IT and business are today," said Rudy Puryear, partner at consultancy Bain and leader of its global IT practice. "What major action can you take in this business that doesn't have IT implications in one form or fashion?"4

Would the position of chief financial officer ever report to some other leader than the head, such as the provost in an institution of higher education? When a CIO or other technical leader reports to someone in the leadership team other than the president, that institution has effectively decided to have the benefits of technology and technical business solutions reinterpreted, rebroadcasted, and potentially redefined. Unfortunately, this can happen because solutions and decisions communicated up the leadership chain change along the way.

In the article "Why Your CIO Should Report to the CEO," E-N Computers reported:

"If the top IT manager instead reports to the top financial person or the head of operations, the voice of IT may not be fully heard 'around the table' of top management. In this case, financial, operations, or other executives can sway the organization's priorities in directions that favor their own departments but do not serve the best interests of the whole organization for the technology it needs.5

Such a situation should be cause for concern. For the college or university to be most effective, it is essential for the CIO to sit at the table where institutional decisions are made. The CIO must be proactively engaged in all levels of business discussions to appropriately steer, recommend, and suggest how the considerable technological and information investment the institution has made can be leveraged as an enabler to facilitate organizational goals and objectives.

Although the role of technology is critical, IT hiring practices for senior positions in higher education revealed that in this current competitive environment, many institutions advertised senior IT positions in higher education that incorporated reporting lines to other vice presidents, the provost, and even to those in finance. In a time when universities and colleges compete for students and need to work strategically to raise graduation rates and improve learning, we need to ask why such reporting practices persist. Based on various online open position announcements for senior IT positions in higher education, the practice of having senior IT personnel report to others than the university president still seems prevalent, as their wording indicates:

- Reporting to the Senior Vice President & Chief Operating Officer, the VP/CIO…

- Reporting to the Senior Associate Dean for Administration & Finance

- As XX's first Vice President-level Chief Information officer

- The Executive Director is a direct report to the Provost/Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs

- The Associate Vice President and Chief Information Officer, reporting to the Executive Vice President of Finance

- Reporting to the Provost, the VP/CIO provides…

- This position reports to the Vice President for Administrative, Enrollment & Student Services

- … invites resumes for a Chief Information Officer (CIO) reporting to the Vice President for Administrative Affairs

- Reporting to the Chief Financial Officer and the Assistant Vice President/CFO

- Reporting to the Vice President, Administration and Finance

- The VP/CIO reports to the Provost

- Reporting directly to the Vice President for Finance and Administration

- Reports directly to the Vice President for Administration and Finance

- Under the general direction of the Vice President for Administrative Services

- Reporting to the Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs

"But if IT reports to the CFO or another officer, then accurate information about and critical analysis of the organization's technology needs may be watered down, reprioritized, or even discarded before it reaches the CEO," pointed out E-N Computers.6 Where the CIO reports is important for information assurance/security to remain a top priority never far from the notice of the university president and senior leaders. The college or university should have a CIO who is a member of the leadership team, reports directly to the university president, and is empowered, authorized, and supported to exercise the appropriate technical judgment to benefit the institution.

Institutional Silos of Technology

Because of the size, scope, course offerings, and complexity of some higher ed institutions, they might have individual technology domains, networks, systems, applications, and structures under the control of specific colleges or departments. Some might argue this approach is not a duplication of services, but required to facilitate the success of the specific program. Still, when colleges and departments establish and operate their own technical operating environments, it often makes effective security and network defense more difficult. This situation can catalyze breaches, as security in these areas are not as robust as the overall security of the enterprise directly under the control of the day-to-day IT organization. Institutions that realize this risk have two options:

- increase security spending to include added or even redundant IT security services and personnel, or

- re-architect the environment from the top with security as an essential driver.

Protecting a standard security infrastructure is nearly impossible — or unrealistic — because of the difficulty of standardizing systems and processes across the enterprise. Similar to how some private industry breaches were perpetrated via third-party systems connected to the infrastructure, educational institutions must consider compromises based on technology directly connected to the enterprise. In the case of higher ed systems, these challenges may lie beyond the span of control or not receive the appropriate attention for political, social, financial, or other reasons. Autopsies of security breaches at colleges and universities often trace the source of entry to a security weakness. Recent audits have shown how this practice of silos of technology can lead to a breakdown in security.

Thomas Barnickel [a state auditor] explained an audit finding where some clusters of computers on the fringes of the campus network were not protected by firewalls. Mainframe computers and other central servers were protected, he said, but there was no campus-wide policy for protecting the local networks of individual departments.7

To understand how and why institutional silos of technology can contribute to insecure information systems, the institution must first be familiar with what technology leaders refer to as an enterprise service architecture (ESA). The ESA is designed and developed around an understanding of how the business should be organized, which is predicated on business goals. These business goals are met through the design of complex interrelated business processes, for which IT must be configured and implemented to support the organization and the underlying business processes.8 IT leaders such as the CIO must work to ensure specific IT systems are designated to support the organization.

With the understanding and knowledge of which systems support the various aspects of the institution, and the technical underpinnings to accomplish this, the CIO can ensure the appropriate defense mechanisms protect systems and their data, and that the defense mechanisms do not disrupt other enterprise components. If systems function as silos under various colleges and institutional compartments with different technology or application standards, the exposed gaps in system functionality weaken the institution's security fabric. This can lead to a compromise of the network.

Talented Technical IT Staff

University budgets do not differ much from everyone else's in the sense that not enough resources are available to address the level of demand throughout the institution. College and university administrations must consider tradeoffs in selecting which areas to fund and where to spend their limited dollars. University leaders need to remember that information systems are one of the few structures that touch every aspect of the operation, and the security of data is vital — it's one of the most important assets of the university. Administrators should also be reminded that in the current digital economy, businesses do not become great in spite of their technology but because of it. However, to achieve the potential value and level of efficiency and effectiveness for systems in place, educational institutions need appropriately trained individuals and administrators. This presents a paradox in that many organizations across the country are experiencing a shortage of talented IT professionals. Unfortunately for higher ed, qualified individuals often come with salary expectations indicative of the rules of supply and demand.

One strategy that has helped many colleges and universities is using tuition remission to attract and retain qualified IT talent, which can benefit the employee and their immediate family members seeking higher education. Even so, we must constantly seek to grow our own talent (develop internal competencies in our employees) and live in a constant atmosphere of succession planning. Clint Boulton, senior writer for CIO.com, explained:

"CIOs are starving for talent, particularly for professionals who can glean insights from large volumes of data, as well as employees who can cultivate digital capabilities and protect corporate assets from hackers."9

Without an adequate, talented, and technically adept staff, the college or university cannot realistically expect to maintain an appropriate level of security over the data in their systems. Furthermore, if these critical assets are not in place, the institution can face having their systems compromised and data stolen without even knowing their systems have been compromised.

Formal Information Security Department

Based on security reporting statistics, hackers are targeting institutions of higher education for security attacks. Nearly a third of CIOs surveyed reported that they had to respond to a major security incident in the past two years. They cited organized cybercrime at the top of this list of attacks, followed by amateur hackers and malicious insiders. Only 22 percent of CIOs said they "feel confident" their organization is very well-prepared to identify and respond to cyberattacks.10

Unfortunately, many colleges and universities believe they have adequately addressed this concern by appointing someone to serve in the security leadership capacity without a staff. Realistically, charging one individual with the responsibility — to implement secure on the network via working through various IT department manages to implement an enterprise security posture is grossly inadequate. The risk is much greater than one fulltime IT professional can address. Wallace Loh, president of the University of Maryland, explained that

"Security in a university is very different than the private sector because we are an open institution. There are many points of access because it is all about the free exchange of information. And that is the challenge for all colleges and universities. In 2014, 50 universities had major data breaches, and not all of them bothered to report it."11

These attacks can often make their way through firewalls and other technical equipment via an e-mail containing a virus. Veronica Rocha noted on January 11, 2017, that a "Community College District paid a $28,000 ransom in bitcoin last week to hackers who took control of a campus email and computer network. The virus locked the campus' computer network as well as its email and voicemail systems."12

Institutions of higher education should seriously consider their current defense strategy; contemplate what will happen when they are attacked (an inevitable event); determine what their internal technical response will be; decide how they will defend the institution via their public relations message; and estimate the cost for damages (monitoring for each account compromised for one year, special security consultants to address the issues, cost of unproductive downtime and operational disruption, loss of potential student enrollment, and negative media portrayal of the administration). Regarding one breach in higher education,

Auditors found that only 15 of more than 500 campus departments lay behind a campus-wide firewall. That meant that in many departments, including the officers of the president and the bursar, workstations could be accessed through student computer labs, dormitories or the Internet.13

Clearly, a formal information security department staffed with trained security professionals — not just a single network security professional, but instead a team of information assurance professionals — is critical to defend the network.

Appropriate Security Framework

Unfortunately, many believe and fall into the misguided notion that cybersecurity is the ultimate tool for securing systems, and therefore leave much of the system under-protected. As a chief information security officer with formal training in information security/information assurance, I understand the vital importance of adopting an information assurance framework. Cybersecurity is not information assurance, nor is it a replacement for an information assurance framework.

While the topic of information security seems synonymous with cybersecurity, and thus the conversation tends to occur from this perspective, a greater concern is potentially overlooked. As an IT security professional, I agree that cybersecurity is a critical tool for defending the network. However, cybersecurity is one tool, not a framework. For defending the network, the appropriate framework on information security, which at its heart is information assurance, should be the wider focus. Within this framework, cybersecurity is one of a few other capable approaches for defending the network. In working with information assurance from the early 2000s in the U.S. Department of Defense, I quickly realized that many higher education institutions had not fully adopted an information assurance framework. For this reason, many institutions are just beginning to understand the critical importance and necessity of information assurance, along with its true value.

Once again, it is important to understand the distinction between network security, cybersecurity, and information assurance. Because of this, just a formal security department is not enough. If the sole purpose of a security department is to oversee and execute cybersecurity and/or network security measures, then the institution is not doing all it can to address the security of its systems. While required to defend the network, network security and cybersecurity should be considered additional tools within a security-in-depth methodology of protecting the network. Because these tools lie within the larger scope of information assurance, a successful university must adopt a formal information security framework.

Institutions of higher education must understand that

Information Assurance (IA) relies on people, operations, and technology to accomplish the mission/business and to manage the information infrastructure. Attaining robust IA means implementing policies, procedures, techniques, and mechanisms at all layers of the organization's information infrastructure.14

An appropriate framework is required to ensure that all efforts to defend the infrastructure are connected strategically and effectively.

Data Security: Everyone's Responsibility

While the security community can make the case for having a CIO, and for him/her to be accessible not just to the university president but also to the entire leadership team, the importance in this reporting relationship has to do with working with university leadership to protect critical information. This must include personally identifiable information for students, staff, and faculty in order to maintain the confidentiality, integrity, and accessibility of critical data. Data security must also ensure all aspects of the university's technical operations to include telecommunication and wireless and network communication are protected. Should anyone think this reporting distinction and the potential cost of a breach are insignificant, you only need to look at the results (and costs) of those universities whose networks were compromised. The state of security is everyone's responsibility, but the CIO must champion that cause and have direct access to the university president to deliver all the news: good, bad, and breached.

Notes

- Joanna Grama, "Just in Time Research: Data Breaches in Higher Education," EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, 2014.

- Linton Wells II, "Understanding Cyber Attacks," in Global Strategic Assessment 2009: America's Security Role in a Changing World, Patrick M. Cronen, ed. (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2009), 57–59.

- Thornton May, "5 Reasons the CIO Matters More than Ever," CIO, February 16, 2015.

- Thomas Wailgum, "Why Is the CFO Still Boss of IT?" Network World, April 22, 2010, quoting Rudy Puryear, a partner at consultancy Bain and leader of its global IT practice, for a CIO.com article titled "From the CEO: 5 Questions CIOs Need to Answer. "

- E-N Computers, "Why Your CIO Should Report to the CEO," June 24, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Scott Dance, "Audit finds flaws remain in UM network security, even after data breach," Baltimore Sun, December 10, 2014.

- Dan Woods and Thomas Mattern, Enterprise SOA, Designing IT for Business Innovation, O’Reilly Media, 2006; 92).

- Clint Boulton, (2016). "More CIOs report to the CEO, underscoring IT’s rising importance," CIO.com, May 24, 2016.

- Ibid.

- Jedidiah Bracy, "UMaryland President: Breach Would Have Bankrupted Many Institutions," Privacy Advisor, March 27, 2014.

- Veronica Rocha, "Los Angeles Valley College pays $28,000 in bitcoin ransom to hackers," Los Angeles Times, January 11, 2017.

- Dance, "Audit finds flaws remain."

- Information Assurance Technical Framework, release 3.1 [http://gravicom.us/downloads/docs/IATF/FtMatter.pdf], September 2002, National Security Information Assurance Solutions Technical Directors.

E. Wayne Rose is vice president of Information Technology and CIO at Bowie State University.

© 2017 E. Wayne Rose. The text of this article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0.