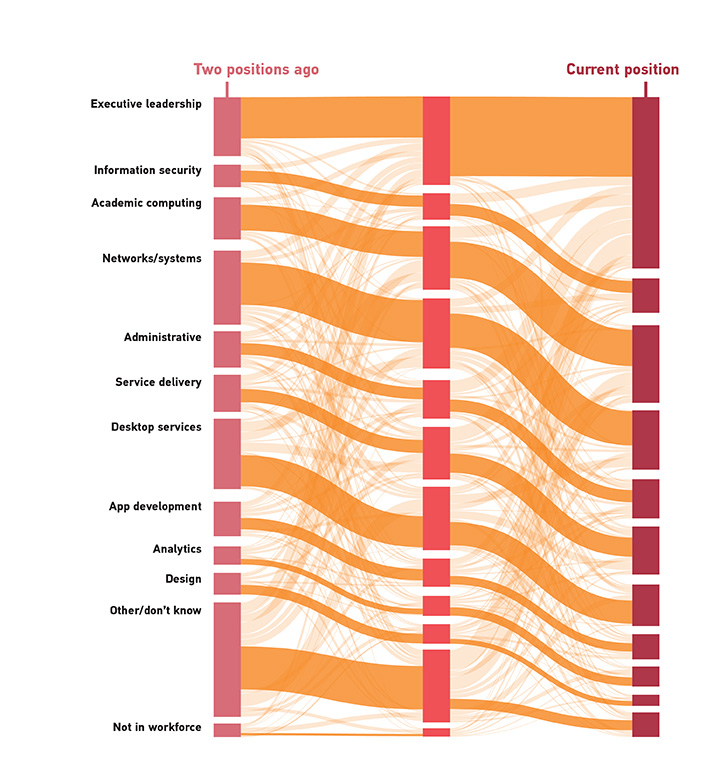

The career paths for higher education IT staff tend to be highly stable, with most individuals remaining in the same job category over time. Those who move into executive leadership positions, however, often change job categories during their career.

The breakneck pace of change in the field of information technology demands constant attention, intense workloads, and long hours from the higher education IT workforce. Dedication to completing daily work and projects with efficiency, while maintaining the high quality of the deliverables for which IT is responsible, means that IT staff might rarely take time to examine the longer arc of their careers. If you are reading this article, we invite you to pause for a moment to reflect on your career up to this point and consider your longer-term aspirations. Even if your own professional story to this point is not reflected in the research findings about career paths and executive skill sets presented here, this research into the higher education workforce can be a valuable way of taking stock, especially for those who aspire to a C-level position.

This article draws on two major lines of research within the most recent EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) higher education IT workforce project. The first draws on data collected for The Higher Education IT Workforce Landscape, 2016, analyzing how previous jobs relate to one's current position and how one's present position shapes the choices of jobs one hopes to have in the future. The second uses data collected for the four studies in the IT Workforce in Higher Education, 2016 research series. These studies of four specific IT leadership positions (the chief information officer, the chief information security officer, the enterprise architect, and the chief data officer) aimed at developing a better understanding of the skills required to execute their duties well. Although we do not intend the results of our research to be prescriptive, we do think that the lessons learned can provide readers with some insight about where they are, how they got there, and what the next steps might be.

The Past

One of the most notable findings of the IT leadership reports is that the IT workforce is quite stable. Most individuals remain in the same sector of IT across multiple jobs over time: one-third to two-thirds of employees in any given sector remain in that same sector from one job to the next.

The data from which these findings come from three questions asked on the IT Workforce Landscape survey:

- What position did you hold two positions ago?

- What position did you hold immediately before your current position?

- What is your current position?

All three questions had the same set of 109 jobs as possible responses, grouped into 12 categories, which we refer to as "IT sectors."1 Figure 1, which breaks down the career moves of those in higher education IT according to these 12 IT sectors, makes clear that the majority of these individuals have been employed in the same sector across multiple positions — at least a third of those in each sector remained in the same sector each time they took on a new position.

The career paths of higher education IT employees tend toward specialization and domain-sector expertise. That is, the best predictors of one's current IT sector are the sectors of one's previous positions. This is of course hardly surprising. When job hunting, one generally sticks more or less with what one knows rather than trying to go into an area that one knows little or nothing about. Although there's quite a lot of common ground across all IT jobs, one would experience a considerable learning curve to gain the appropriate skills in going from, for example, web design to information security, or business intelligence to academic computing.

There are no clear and definitive paths to IT executive leadership. Executive leaders emerge from virtually all higher education IT sectors, though not from all sectors uniformly. Individuals whose previous positions were in the sectors of analytics, design, desktop services, and networks and systems are less likely to currently be executive leaders than individuals from other sectors.2 That said, having a background in more than one sector is a positive benefit: switching IT sectors at least once in one's career increases the probability of holding an executive leadership position later. In other words, despite the real and understandable tendency to remain within a sector and develop expertise in it, the "reward" of IT executive leadership more often goes to those who change sectors. Given the importance of IT leadership to institutions of higher education, this finding indicates that the field of possible candidates for those positions may be wider than previously assumed.

The Present

EDUCAUSE and Jisc recently collaborated on two reports that address common concerns: understanding the skills required by technology leaders in higher education, and helping midcareer IT professionals prepare to become the next generation of IT leadership. Those two reports present findings from discussions among working groups of CIOs and other IT leaders.3 A number of issues appeared time and again during the course of those discussions, issues that were articulated in the reports as "key roles" played by IT leaders. Those key roles, and the skills necessary for them, became the starting point for questions asked of IT leaders in all four leadership role surveys and the frame used in the analyses presented here.

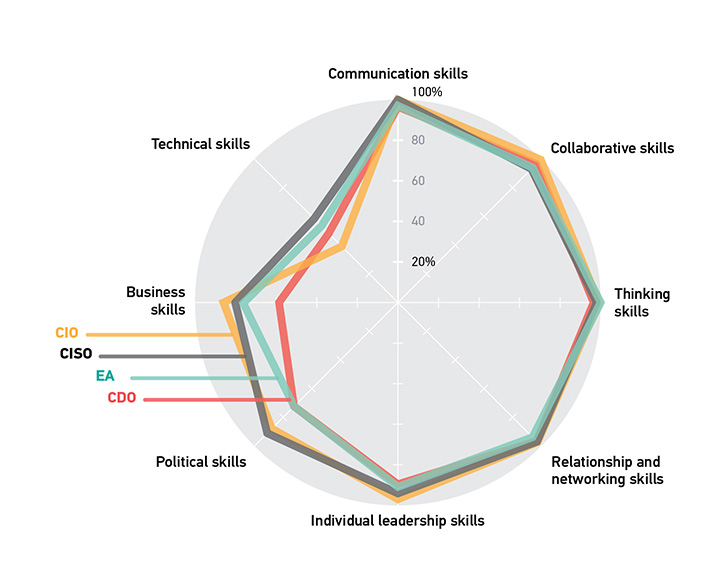

Although all IT leadership positions require some combination of the same skill categories, the specific skills necessary for success in IT leadership are naturally different for different leadership positions. On each of the four surveys, respondents were asked a set of questions about the extent to which they possess specific skills, about 25-40 specific skills in all.4 These position-specific skills roll up into a set of eight broad skill categories that are shared across all of these IT leadership positions.

Respondents to all four surveys were asked to rate the importance of these skill categories for success in higher education IT leadership.5 As shown in figure 2, leaders in all four positions provided strikingly similar ratings of the importance of these skill categories6; the order in which these categories are ranked is almost identical across all four positions. This makes a strong statement about what is most important for institutional leadership. Indeed, the similarity of these ratings indicates that despite the differences across these four positions, the important factor here is that they are institutional leadership positions.

IT leaders in each of the four positions rated communication as either the most or second-most important skill category. This should surprise no one, given that written and oral communication are almost universally acknowledged as critical for personal and organizational success.7 Indeed, the top 5 skill categories rated most important by all four positions are all soft skills: communication, collaborative, thinking, relationship and network, and leadership skills. It is of course widely accepted that skills of this type are critical for leadership roles, but it is nevertheless useful to have data that so clearly bear this out.

Also noteworthy is that, across the board, the category rated the least important concerns technical skills. This is perhaps unexpected for a set of positions that are specifically IT-related. However, this is the flipside of the previous finding — that soft skills are uniformly ranked as the most important skills. Technical skills are important for success in the positions that feed into these leadership roles, but once one is in a leadership role, other skills become more important.8 In short, IT leadership positions are not primarily about IT: IT leadership positions are fundamentally about institutional strategy and politics.

As mentioned above, each of the eight skill categories was broken out into specific skills unique to each position, and respondents were asked questions about the extent to which they agree that they possess those specific skills. Respondents in all four positions evaluated their possession of most of these specific skills lower than their rating of the importance of the corresponding skill category. For example, 99% of CIOs rated thinking skills as important for success, but only 55% agreed that "I identify trends before my peers." In another example, 80% of CISOs rated business skills as important, but only 70% agreed that "I have deep knowledge of current legislation, standards, and compliance requirements."

This finding, combined with the fact that very few respondents in any of the four leadership positions have earned professional certifications in their chosen areas of IT, indicates that there are many opportunities for organizations that provide professional development in the soft skills necessary for success in leadership roles. Indeed, respondents across all four surveys acknowledged that these soft skills are harder to develop than technical skills.

A key finding in all of the ECAR reports on leadership positions is that individuals in these four positions — as well as those who aspire to these positions — have a great need for professional development to enable individuals to grow into new roles throughout their career. This is a call to action for supervisors throughout the institution to provide time and resources for employees to pursue professional development opportunities appropriate to their career paths and the needs of the institution. IT leaders emerge from across the institution and from across all IT sectors. It therefore serves the institution — and the field of higher education generally — to cultivate future leaders across the institution and across all IT sectors.

The Future

In addition to the two past-facing questions discussed in the first section, an additional pair of future-facing questions were asked on the most recent IT Workforce Landscape survey:

- What position do you aspire to hold immediately after your current position?

- What position do you aspire to hold after your next position (two positions in the future)?

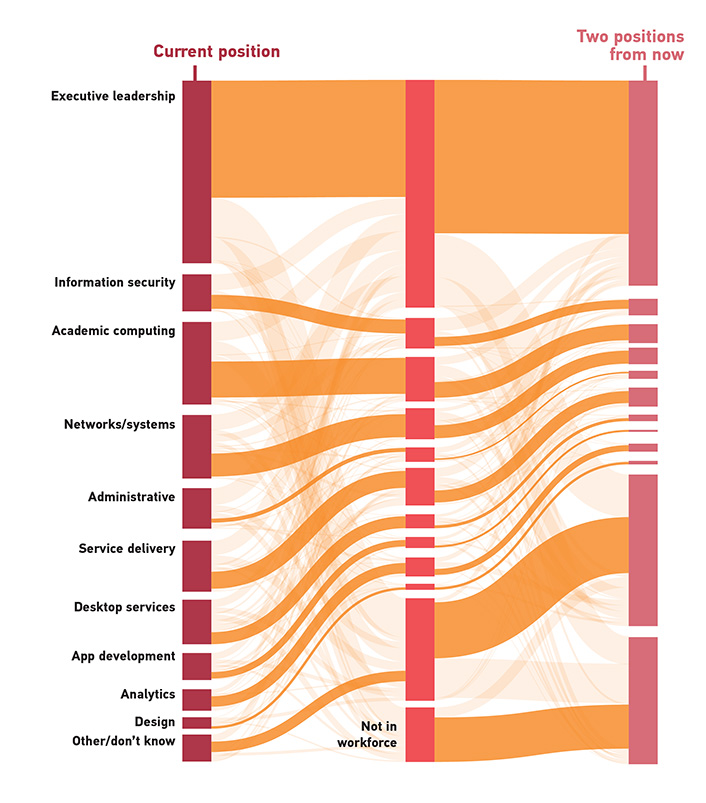

Like the past-facing questions, these had the same set of 109 jobs as possible responses, grouped into 12 IT sectors. Figure 3 breaks down aspirational career moves of those in higher education IT according to these 12 IT sectors.

Even a quick glance at figure 3 makes two findings clear. First, leadership positions exert a strong pull, as a large percentage of the IT workforce aspire to those positions. Second, the number of staff in each sector shrinks steadily over the next two positions, as nearly 1 in 10 current higher education IT employees expect to leave the workforce (i.e., retire) immediately following their current position and fully 21% expect to do so after their next position. An even larger percentage of current higher education IT employees plan to do something else within IT (e.g., become a consultant or take on a new position that does not yet even exist) or leave IT altogether.

To put this another way, our data suggest that the proportion of IT staff is increasing in only three areas over time, two of which are leaving the profession. For IT staff who remain in the IT workforce, executive leadership is the only area of anticipated growth. Of course, not everyone who aspires to executive leadership will in fact achieve that goal. But the fact that so many do, and so many more wish to, leads inevitably to attrition in all other sectors of the IT workforce.

As IT staff move up into executive leadership or out of the IT workforce entirely, positions in these sectors need to be filled by younger employees. As discussed above, there is a need to cultivate staff for IT leadership positions. But mirroring this, there is a need to recruit new IT staff. Recruiting and hiring for IT positions is always challenging, and it can be especially so for institutions of higher education, which often cannot match the salaries offered by the private sector for similar IT positions.9 The IT Workforce Landscape survey found, however, that IT staff are quite loyal to higher education — greater than 50% agreed or strongly agreed that it is very important to them to work in higher education rather than in any other industry. Indeed, a majority (55%) of respondents said their next position will be in higher education IT, and about a quarter (27%) said they expect their next position to be at the same institution.10 The IT Workforce Landscape survey also found that issues related to quality of life were the most important factors for retaining IT staff at their current institution.11 This knowledge should be valuable for institutions in recruiting and retaining IT staff.

Conclusion

The career paths of higher education IT employees are incredibly stable, with most individuals remaining in their respective IT sectors over time. Disruption to this pattern comes in the form of longer-term aspirations to move into executive leadership positions and plans to leave either higher education or the IT workforce or both. Each of these scenarios pose different challenges to growing and maintaining the staffing levels required to run an IT organization. Our data offer some practical solutions that may mitigate or moderate these threats to its stability.

First, our data suggest an array of skill sets that are decidedly not technical but are critical for the future leaders of IT organizations to possess. To cultivate the soft skills of leadership required to advance, we offer several suggestions. For those in the early stages of thinking about these transitions, seek opportunities to develop new technical skills. This will allow you to transition from one IT sector to another; the likelihood of achieving a leadership position is improved by switching sectors at least once in one's career. Additionally, seek professional development opportunities that cultivate the soft skills required to run a higher education IT organization and/or identify a mentor in a leadership position who can nurture growth in these areas.

Second, to retain higher education IT staff, consider the ways in which the institution or organization can help employees prioritize quality-of-life issues. Quality of life is the most important factor in keeping employees at their current institution, eclipsing the tangible compensation of both salary and benefits. Consider job retraining or new opportunities for those who may need new challenges to remain engaged in their work.

Third, there is little one can do to stave off the steady march of time that leads people to leave the workforce completely at the end of their careers. However, time taketh away and time giveth to the workforce — as older people retire, younger people are entering the workforce. To facilitate the replacement of retirees with new blood requires understanding the needs and aspirations of the emerging IT worker. Competition with private sector employers puts higher education IT at something of a disadvantage with respect to salary, but highlighting the intangible quality-of-life issues associated with the higher purpose of educating people, working in an intellectually stimulating environment, and providing opportunities for professional growth may very well attract the best of the best.

Acknowledgments

This article is derived from a presentation titled "Roads Taken, or What Robert Frost Can't Tell Us about Higher Ed IT Career Paths," given by the authors at the EDUCAUSE Connect conferences in Portland, Oregon, in March 2017 and Chicago, Illinois, in April 2017. The data for the analyses in this article come from the Landscape Report and the IT Leadership Role Reports in the IT Workforce in Higher Education, 2016 research series. Many thanks are due to Ben Shulman for his preparation of the data set on which these analyses are based; to Mike Roedema for his work on developing the career path interactive; and to Kate Roesch for creating the graphics for this article. Thanks also to the Connect attendees in Portland and Chicago for allowing us to interrupt their lunch with this presentation.

Notes

- The response for these questions was n = 1,188.

- See Career Paths: Higher Education CIOs and Career Paths: Higher Education IT Sectors.

- EDUCAUSE and JISC, Technology in Higher Education: Defining the Strategic Leader (Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE in partnership with Jisc, March 2015); EDUCAUSE and JISC, Technology in Higher Education: Guiding Aspiring Leaders (Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE in partnership with Jisc, February 2016).

- These specific skills will not be discussed here, in favor of a focus on commonalities across IT leadership positions; for more data on IT leaders' self-evaluation of their skills, see the 4 IT Leadership Role Reports. As a quick example, however, all four IT leadership surveys contained the communication skills question "I communicate with others by adapting the message for the intended audience." Many of the technical skills questions, however, differed across the four leadership positions: CIOs, for example, were asked about the degree to which they agreed with the statement "I trust my staff to be the technology experts," while CDOs were responded to the statement "I have experience working with metadata."

- Responses to this question were on a Likert scale, ranging from not at all important to extremely important.

- Specifically, figure 2 shows percentages of IT leaders who evaluated the importance of these skill categories as very important or extremely important.

- Greg Satell, "Why Communication Is Today's Most Important Skill," Forbes, February 6, 2015.

- This is a central point made by Marshall Goldsmith in What Got You Here Won't Get You There: How Successful People Become Even More Successful (New York: Hyperion Books, 2007). This is also arguably one factor that leads to the ubiquity of the Peter principle, the well-known and only slightly tongue-in-cheek management principle that everyone rises to his or her level of incompetence. A technically skilled employee may be promoted to successively higher positions in an IT organization, but once taking on a leadership role, those technical skills are no longer the skills that are important for success: see Laurence J. Peter and Raymond Hull, The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1969).

- See May 2016 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates, United States, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016.

- See Career Paths: Institutions and Industries.

- Jeffrey Pomerantz and D. Christopher Brooks, The Higher Education IT Workforce Landscape, 2016, research report (Louisville, CO: ECAR, April 2016), 31–32.

Jeffrey Pomerantz is Senior Researcher with the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research.

D. Christopher Brooks is Director of Research with the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research.

© 2017 Jeffrey Pomerantz and D. Christopher Brooks. The text of this article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0.