Key Takeaways

-

Most information security awareness professionals in higher education have earned postgraduate degrees, hold technical certifications, and have worked in the information security awareness field for 10 or more years.

-

The managers leading higher education information security awareness programs tend to those duties part-time, and the programs have limited staff and budgets.

-

Planning of most information security awareness activities occurs as opportunities arise, with a flexible approach applied to compliance activities.

Human behavior is complicated, and information security fatigue is high.1 Numerous studies have proven repeatedly that, given the opportunity, many of us will trade (forgo? sacrifice?) security for expediency. Hungry? Trade your password for chocolate.2 In need of wireless access while on the go? Agree to an overbroad end-user license agreement to get online.3 Want to download the latest, greatest app? Give up your firstborn child.4

In light of these behaviors, it seems that ensuring basic levels of end-user security awareness might be difficult, if not impossible. Yet, such an education effort is critical at higher education institutions, where members of the institutional community have access to an abundance of sensitive and confidential data. From alumni donation records to student and staff financial information, from raw research data to valuable developed intellectual property, institutional data must be protected from the vagaries of human behavior. Institutions recognize this dilemma, and as a result information security awareness programs are prevalent throughout higher education. In 2015, a majority (74 percent) of U.S. institutions required information security training for faculty or staff, and 27 percent of institutions required such training for students.5

These programs seem abundant. Yet, what do information security programs at colleges and universities look like? How are they funded and staffed? How mature are they? And, who are the professionals who direct these programs? What are their backgrounds, and what are the skills necessary to excel in these jobs?

Programs

In 2016 the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) studied the state of the higher education information security awareness program landscape through a partnership with the SANS Institute. This research surveyed 369 information security training and awareness professionals. The educational service sector, which includes colleges and universities, was the largest sector represented in the research and constituted 21 percent of the survey responses.6 The research was designed to capture the demographics of information security awareness programs across many industries.

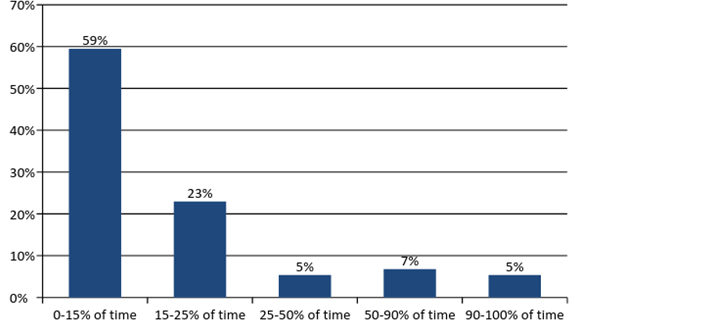

The research found that higher education information security awareness programs are lean, meaning that they are typically led by managers who attend to their awareness duties with only a fraction of a full-time employee’ times; most devote no more than 15 percent of their time to training and awareness activities (see figure 1). Most programs (61 percent) have only one, or less than one, FTE.

Figure 1. Percentage of time devoted to security awareness activities (n = 74)7

In addition to being leanly staffed, these programs also tend to have small budgets. In 2016, over three-quarters of survey respondents didn't know what their annual budget would be or reported budgets of less than $5,000. Only 23 percent of the respondents reported a budget of more than $5,000. Many survey respondents reported that resources and time were the biggest challenges facing their information security awareness programs.8

Practices

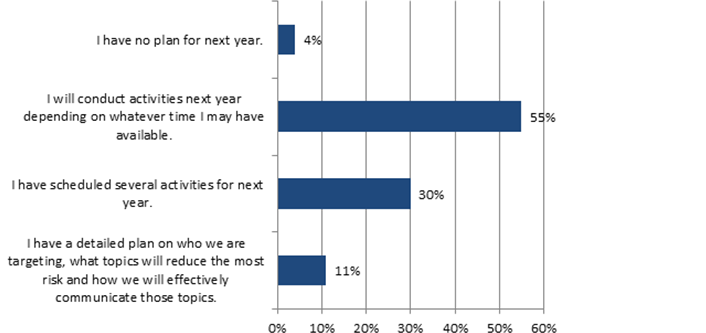

Higher education information security programs tend to be agile and opportunistic in creating educational opportunities for the institutional community. This is not surprising since information security awareness programs are not led by a dedicated awareness manager, comprise small teams, and have minimal budgets. Slightly more than 41 percent of information security awareness professionals had developed a detailed yearly awareness plan or had scheduled multiple awareness activities. A majority (55 percent) of these professionals reported that they would conduct awareness activities as time permits (see figure 2).9

Figure 2. Organizations with 2016 security awareness program plans (n = 71)10

End users often challenge even the best security awareness programs, and effectively influencing end-user behavior to decrease risk is a core component of such programs. Respondents to the research identified end users as the third-largest challenge to effective security awareness programs (behind “resources” and “time”). End-user behavior is often quite complex. For example, in 2015 EDUCAUSE found that, while a majority of students protect their computing devices with strong passwords, over a quarter of them have shared the password for those devices.11 Fortunately, the culture of higher education seeks to teach, and not punish, pernicious password-sharers. Not a single higher education information security program survey respondent cited a punitive approach to awareness compliance, and a majority of institutions (58 percent) reported a flexible approach to behavior correction.12

Professionals

In the second half of 2015, the Higher Education Information Security Council (HEISC)13 Awareness and Training Working Group conducted a survey of security awareness professionals. The goal of the survey was to look closely at the background, certification, and training needs of the professionals responsible for information security awareness programs at colleges and universities. Over 45 individuals with primary institutional responsibility for information security awareness programs responded.14

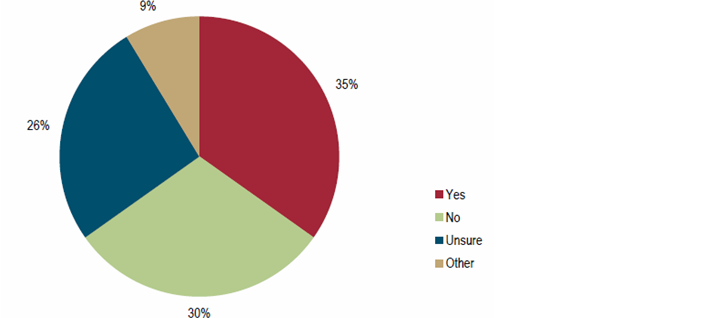

The majority of information security awareness professionals are highly educated: most hold at least a bachelor’s degree, while more than half have earned postgraduate degrees. In addition, almost all respondents (84 percent) hold multiple certifications that tend to be highly technical in nature (e.g., CISSP, CISM, ITIL, GSEC).15 Although a certification for information security awareness and training does not exist at this time, at least one-third of respondents believe that awareness and training certification would be valuable for their career (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Perceived value of awareness and training certification16

Security awareness professionals provide a distinct skill set and knowledge base for their campus information security awareness programs. The identified soft skills, such as public speaking and relationship building, are important enablers of successful campus information security programs.17 The importance of soft skills cannot be stressed enough to higher education IT professionals — those skills help bridge the gap between technical and nontechnical conversations. For example, being able to communicate effectively has been identified as the most important soft skill for the entire workforce of higher education IT professionals, yet the importance of the skill exceeds IT workers’ proficiency in it.18

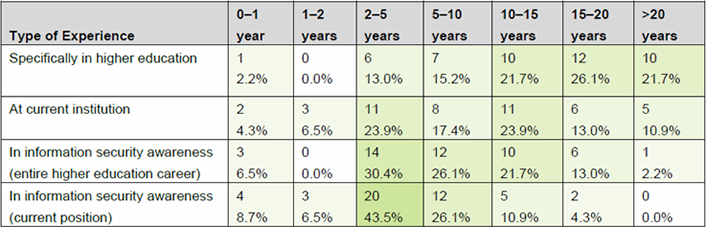

The research from the HEISC awareness and training professionals confirmed the SANS research: Higher education information security awareness professionals often have duties outside of the awareness and training sphere.19 Most respondents to the HEISC survey indicated that they are responsible for tasks beyond security awareness that may include compliance, privacy, risk management, or IT communications.20 They also are not newcomers to their roles: more than 60 percent of these professionals have worked in information security awareness positions in higher education for more than five years (see table 1).

Table 1. Survey respondent experience21

Conclusion

Information security programs in higher education focus on promoting awareness and changing human behavior. The existence of such programs is featured heavily in models that measure the overall maturity of higher education information security capability.22 Have you ever passed up a tasty treat when asked to share your user credentials? Do you think twice before joining public Wi-Fi networks? Do you read the end-user license agreement before you download the hottest new app? If so, you may be able to thank an unsung hero: your campus information security awareness professional. These professionals, and the programs they run, help turn ordinary students, faculty, and staff into savvy end users who nimbly avoid the Internet’s most perilous traps: phishing e-mails, malware, shady websites, and social engineering attacks.

Notes

- National Institute of Standards and Technology, “‘Security Fatigue’ Can Cause Computer Users to Feel Hopeless and Act Recklessly, New Study Suggests,” October 04, 2016.

- BBC News, Passwords Revealed by Sweet Deal,” April 20, 2004.

- Erin Cargile, “4th Grader’s Project on Cyber Security Proves People Will Click on Anything,” KXAN.com. August 23, 2016.

- David Kravets, TOS Agreements Require Giving up First Born — and Users Gladly Consent, Ars Technica, July 12, 2016.

- EDUCAUSE Core Data Service Almanac, All U.S. Institutions, 2015 data, February 2016.

- Joanna L. Grama and Eden Dahlstrom, “Higher Education Information Security Awareness Programs,” research bulletin (Louisville, CO: ECAR, August 8, 2016).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Eden Dahlstrom, with D. Christopher Brooks, Susan Grajek, and Jamie Reeves, ECAR Study of Students and Information Technology, 2015, research report (Louisville, CO: ECAR, December 2015).

- Grama and Dahlstrom, “Higher Education Information Security Awareness Programs.”

- The EDUCAUSE Cybersecurity Initiative is led by the Higher Education Information Security Council (HEISC), whose mission is to support higher education institutions as they improve information security governance, compliance, data protection, and privacy programs.

- Ben Woelk, “The Successful Security Awareness Professional: Foundational Skills and Continuing Education Strategies,” research bulletin (Louisville, CO: ECAR, August 10, 2016).

- Visit the HEISC Information Security Guide’s Training and Certifications resource page to learn more about common information security certifications.

- Woelk, “The Successful Security Awareness Professional.”

- Ibid.

- Jeffrey Pomerantz and D. Christopher Brooks, The Higher Education IT Workforce Landscape, 2016, research report (Louisville, CO: ECAR, April 2016).

- See text accompanying figure 1.

- Woelk, “The Successful Security Awareness Professional.”

- Ibid.

- The EDUCAUSE Benchmarking Service includes information security awareness training as an element of the security services and operations dimension in its information security maturity index.

Joanna Lyn Grama is director of Cybersecurity and IT GRC Programs for EDUCAUSE.

Valerie M. Vogel is senior manager of the cybersecurity program for EDUCAUSE.

© 2017 Joanna Lyn Grama and Valerie M. Vogel. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0.