Key Takeaways

- Two University of Wisconsin–Madison MOOCs added in-person activities to supplement the online experience and reach statewide audiences.

- These targeted interactive events and targeted interactive partnerships reached beyond MOOC participants to reach local communities where the events occurred.

- Evidence showed that participation in either type of event improved appreciation of the learning experience and strengthened the feeling of connection with the university.

Tromping the Wisconsin backcountry with a group of beginning hunters, rifle in hand and snow in your boots, is not the typical massive open online course (MOOC) experience — unless you took a MOOC from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 2015. (See "MOOCs for Wisconsin and the World" in this publication, March 2, 2015.) In-person activities supplemented the online experience: targeted interactive events (TIEs) and targeted interactive partnerships (TIPs). This article explores the lessons we learned, both positive and negative, and how we engaged our supporters to build dedicated communities of learners using both the TIE and TIP models.

Targeted Interactive Events

The first MOOC, "The Land Ethic Reclaimed: Perceptive Hunting, Aldo Leopold, and Conservation," featured two major events. "From Hunt to Harvest," a two-day event, gave 26 beginning hunters a crash course in handling and shooting rifles. Accompanied by mentors and dog-handlers, they roamed the Pine Island Wildlife Area in search of pheasant on the first day. The second day included a hands-on deer butchering workshop; a cooking demonstration with a hosted lunch featuring local foods and wild game; "flashtalks" by wildlife and ecology experts; a hunting/outdoors-related fair; dog training workshops; and guided tours of Aldo Leopold's hunting shack.

In the second major event for "The Land Ethic Reclaimed," Steve Rinella, a television personality and author of Meat Eater, came to campus for two appearances: an intimate talk with invited guests and a larger public lecture followed by a meet-and-greet with Wisconsin fans.

For the "Climate Change Policy and Public Health" MOOC, a New York Times journalist hosted a well-attended panel of experts at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting in Chicago. This event brought together key thinkers involved in major climate change and public health initiatives to advance the topic among healthcare professionals.

Some of the lessons we learned from holding these face-to-face events1 included:

- Dedicated staff with expertise in outreach were critical to planning and running successful community engagements.

- Outreach staff observed that participants were especially enthusiastic when presented with activities that allowed them to directly engage with university faculty and staff.

- Events that had a partner closely involved in planning and marketing the event were more successful in reaching and engaging local populations.

Targeted Interactive Partnerships

For the "Changing Weather and Climate in the Great Lakes Region" MOOC, we developed a TIP with the Wisconsin Library Service (WiLS) and 21 participating libraries across the state. These partners entered the process early and received training from the MOOC instructors in advance of the course debut. The partners then set up and promoted discussion groups at their libraries, and the instructors attended at least one of the library discussions in person. Much of Wisconsin is rural, which often means unreliable or nonexistent access to high-speed Internet. For this population, the face-to-face discussions supplied a unique entry point into the course content. Approximately 200 people regularly attended these face-to-face MOOC discussion sessions across the state.

After receiving feedback from the partner libraries, a few key best practices became evident:

- Partners appreciated being brought in early and given the chance to provide input on content and ask questions. The partners did not want to appear ill-informed in front of community members and patrons, and this initial training was important in making them feel both comfortable with the content and motivated to promote the discussions.

- The fact that the MOOC instructors committed to attending at least one discussion in person was important to participants and partners. Additionally, for many participants this was the first time they could have a conversation with an instructor from the state's flagship institution.

- Setting and meeting deadlines was critical. The partners had to wait for the MOOC team to provide materials, and they had to schedule staff, rooms, time to make copies, etc. Delays or changes had ripple effects for these partner organizations.

This TIP aimed to engage local communities in the MOOC and give them ownership of a topic. We hoped the partnerships would bring in individuals who would not normally participate in a MOOC and make the material more approachable.

Which Worked Better?

We decided to compare the TIEs associated with "The Land Ethic Reclaimed" MOOC and the TIPs associated with the "Weather and Climate" MOOC through a survey at the end of each. We wanted to understand the relative effectiveness of these two approaches to engagement in terms of learner motivation and perceptions of their classmates. Table 1 shows the results.

Table 1. TIE and TIP surveys

|

|

Land Ethic Reclaimed MOOC (TIEs) |

Weather and Climate MOOC (TIPs) |

|---|---|---|

|

Total Survey Responses |

805 |

655 |

|

Number Participating in TIE or TIP |

58 |

83 |

|

Percentage of Survey Responses |

7.2% |

12.7% |

Motivation

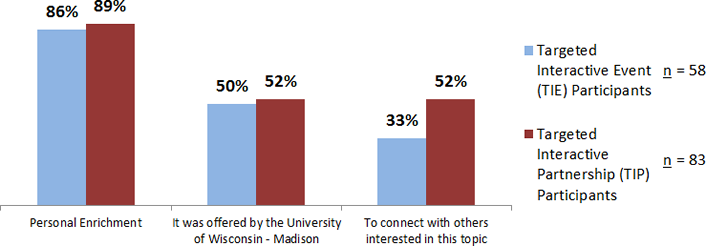

Both TIE and TIP participants had a similar primary motive for taking the MOOC courses, as did all MOOC participants: personal enrichment. However, TIE participants were significantly less motivated by a desire "to connect with others interested in this topic" than were TIP participants.

Figure 1 answers the question of what motivated participants to take the MOOC. The percentages in the graph indicate the number of participants by percentage who chose among the three options of personal enrichment, offered by the flagship university, or to connect with others interested in the same topic.

Figure 1. "What motivated you to take this MOOC?"

We see that individuals who participated in a TIP came to the MOOC with a greater desire to connect with others on a topic than did participants in TIEs. It is difficult to know whether this desire to connect with others would have been met in other ways in the absence of a TIP; however, across all of the other MOOCs in the UW–Madison series, the motivation to connect with others fell in the 20–30 percent range. This provides a bit of circumstantial evidence that the TIP might be an important element for individuals who place a high degree of importance on the social context of learning.2

Classmate Perceptions

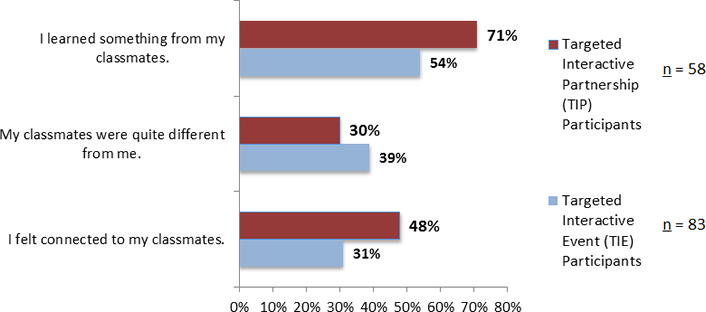

An examination of these TIE and TIP contexts relative to how similar or different these participants viewed their MOOC classmates appears in figure 2. As the figure illustrates, participants in the TIP felt they learned more from their classmates and felt more connected to them than TIE participants. TIE participants were slightly more likely to report that they felt quite different from their classmates. The percentages represent those who agreed with the statement on the left in the graph, with numbers rounded to the nearest whole number.

Figure 2. Classmate perception ratings

Outcome Measures

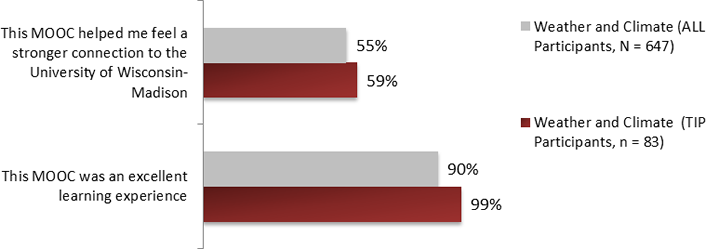

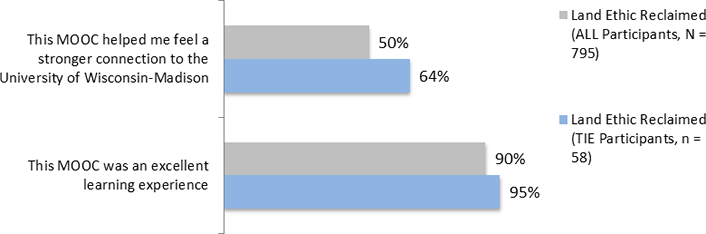

The issue of connection to classmates presents some interesting differences between TIEs and TIPs, although it is not clear whether there were differences on any broader outcomes of interest. To address this question, we examined two measures: perception of the learning experience, and the degree that the experience fostered a connection to UW–Madison. To obtain these measures, we compared the survey responses to those of all the MOOC participants who did not participate in a TIE or a TIP, as shown in figures 3 and 4. Note that percentages indicate those who agree with the two outcome statements at the left of the graph. Percentages are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Figure 3. Outcome measures comparing TIP participation

Figure 4. Outcome measures comparing TIE participation

In terms of key outcome measures, not much difference separates TIPs or TIEs, but note the modest effect for participating in either a partnership or event experience versus the MOOC alone. A moderately positive impact from participating in these outside activities manifests itself in the perception of the learning experience and in the connection back to the university.3

Implications and Discussion

Our findings present some interesting points with implications beyond MOOCs. TIPs and TIEs provide a means by which online education can introduce real-world authentic learning experiences. Understanding some best practices and relative impacts of each approach will be important as higher education institutions consider ways to engage and draw in new learners. While TIEs yielded higher perceived ratings of value and connection to the originating institution, TIPs, when done well, can more deeply engage new partners and learners who previously had little or no connection with the university. Both TIPs and TIEs can validate a university by providing direct access to faculty and staff who may not have the opportunity to engage directly with people throughout the state. In addition, faculty and staff are exposed to learners outside the university who can inform and enrich their own work. It is possible for these face-to-face, interactive experiences to facilitate learning in both directions.

To create successful learning engagements, however, requires time and a skilled team. Even in the case of partnership events, team members with outreach and marketing expertise need to be involved. In general, meaningful connections that foster educational exchanges outside of the immediate university setting do not happen quickly — partnerships need to be carefully identified, cultivated, and sustained to work well.

Surprisingly little research examines different types of ancillary events relative to a core learning experience. As lifelong learners become a greater focus of instruction, however, understanding the impact of these types of events will become increasingly important. This early examination is a first step at highlighting best practices and lessons learned around different types of learner activities.

Key Lessons from the 2015 MOOCs

- Think about and define your audience before designing the MOOC. These audiences are not the same as the traditional classroom audience.

- Larger numbers of participants do not necessarily mean larger numbers of active or engaged participants. In fact, sometimes the inverse is true, with smaller numbers of engaged participants.

- Most local Wisconsin event and partnership attendees heard about these opportunities because of promotion outside of the MOOC. Some became MOOC registrants retroactively.

- While the environmental theme initially drew many people to join the MOOCs, some partners and participants expressed a desire for more thematic variety.

As our approach to MOOCs evolved, we shifted from a strictly online, course-based approach to a community-engaged approach that leveraged partnerships and face-to-face events. In the end we saw that our virtual classroom was strengthened in unexpected ways by real relationships with partners and community members. Although there wasn't a direct relationship between people taking the MOOCs and people coming to the events, the events provided a unique opportunity to bring new audiences to the MOOCs, including those who did not naturally gravitate toward virtual learning. Partnerships offered a similar opportunity to engage new audiences in their own community spaces. In these spaces, institutions of higher education can learn how to design learning experiences that speak to local concerns, reinforcing the value of their teaching, research, and outreach to the population of their home state.

Recommendations

- When working with partners, listen first. Early conversations should highlight partner goals as well as university goals. Details about the partnership — longevity, roles, hosting responsibilities — should be negotiated with some understanding of an outsider's perspective of the institution. It is easy to collaborate and share costs, but a true partnership is transformative and requires more than a transactional interaction.

- If you don't know the communities involved, do your research. Skilled outreach work can be the key to understanding these often complex contexts, and such intelligence can be the difference between good partnerships and events and inspired ones. Our outreach specialists spent the majority of their time out of the office in community settings for face-to-face interactions. Being mindful of the investment involved here, and the return on that investment, can also help in defining and refining the goals of the enterprise.

- Institutions should not rely on the hosting platform but take some ownership of how and to whom they market MOOCs and other open online learning opportunities. For us, leveraging existing university communications and marketing support to develop a comprehensive marketing plan was key. Others might want to consider outside, professional resources. For the targeted, high-touch, university-driven approach we took to communicating and engaging with learners and community members, it was important to put the UW–Madison name and face on all our communications. Regardless of the approach, be intentional with how you engage with your audience.

Where will we go next? Though we are not currently producing new MOOCs, we know that as digital learning becomes more sophisticated and open educational resources become more readily available, integrating these assets and using them in the service of meaningful learning is essential. What might these learning experiences look like? Understanding and creating impactful combinations of events and partnerships together with digital content is our newest exploration. One of our answers for now [https://uwnarratives.wisc.edu/] uses short video and audio media to address the broader-impact imperatives of grant-funded faculty. In this project, we use online resources that are shorter, more portable, and generally designed to fit into the lives of today's learners. We will explore how partnerships and events might enhance this digital outreach, thus sparking unique relationships with new learners in Wisconsin and around the world.

Acknowledgments

Because the University of Wisconsin–Madison MOOCs have been a collaborative effort, the authors wish to thank the MOOC faculty and course design team members, consisting of instructional designers, librarians, data custodians, evaluators, and communication experts. We also want to thank our campus Educational Innovation co-leads, advisory board, and point people, who offered wise advice along the way. Thanks to Linda Jorn, Michael Fay, Greg Konop, and Dean Robbins for their assistance with this article. Finally, a special thank you to outreach specialists Terry Ross and Emily Sprengelmeyer for all of their work in 2015.

Notes

- While these were three major events, the outreach team attended smaller events happening in the community. The estimated number of event attendees across all the MOOCs was roughly 3,500.

- Albert Bandura, Social Learning and Personality Development (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1963).

- It is especially worth noting that among the TIE participants, 30 of 58 individuals had no current or prior relationship with the university, and among the TIP participants 58 out of 83 individuals had no prior relationship with the university.

Jeffrey Russell is vice provost for Lifelong Learning and dean, Division of Continuing Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Linda Jorn is assistant vice provost for Learning Technologies and director of Division of Information Technology, Academic Technology.

Joshua Morrill is a senior evaluator, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Lika Balenovich is project manager, Educational Innovation, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Terry Ross is project manager, Division of Continuing Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Mary Thompson is assistant dean, Division of Continuing Studies, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

© 2016 Jeffrey Russell, Linda Jorn, Joshua Morrill, Lika Balenovich, Terry Ross, and Mary Thompson. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.