Key Takeaways

- Online, competency-based WGU has developed a model that allows the university to deliver personalized learning to its ever-increasing student body — currently over 70,000 students.

- All WGU faculty and systems support student success, providing individualized pacing, coaching, intervention, and support.

- On national surveys of graduates, WGU graduates report better employment outcomes, stronger employee engagement, and higher levels of graduate well-being, validating the effectiveness of the WGU model.

Personalized learning is evolving rapidly, with many different approaches and technologies that promise to improve learning by adapting some or all of an educational system to each learner's needs and goals. The New Media Consortium's Horizon Report: 2016 Higher Education Edition classifies personalized learning as a "Difficult Challenge: Those that we understand but for which solutions are elusive."1 The same report and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation website for postsecondary success suggest that personalized learning, though promising, has not been adequately demonstrated at scale.2 The model built by Western Governors University (WGU) has been refined over the last 19 years around a model of competency-based education (CBE) for all 70,000 of its students.3 We will describe WGU's personalized learning approach and present evidence to support its effectiveness at scale.4

Defining Personalized Learning

Before describing WGU's approach to personalized learning, we propose a definition broad enough to encompass the models being practiced. The Glossary of Education Reform, created by the Great Schools Partnership, describes personalized learning as a form of student-centered learning implemented through a "diverse variety of educational programs, learning experiences, instructional approaches, and academic-support strategies that are intended to address the distinct learning needs, interests, aspirations, or cultural backgrounds of individual students." The key in this description is that personalized learning combines many parts of an educational system and encompasses more than technology-only solutions. WGU has implemented personalized learning by rethinking traditional education to address the individual needs of learners.

Principles for Implementing CBE

WGU's success with students is characterized by the following principles for implementing a personalized approach based on CBE:

- Measure learning and not time: each student is provided with the time needed to master the competencies.

- Competencies align with employers' expectations: students attend WGU to become prepared for a profession and the program competencies also align with the student's personal learning goals.

- Provide individualized support: this principle is designed to help each learner succeed.

- No waiting to learn: once mastery of the competencies in a course has been demonstrated, the student advances to the next course immediately.

- Regular and substantive progress: students are encouraged to engage regularly and make significant progress each term to achieve their personal educational goals.4

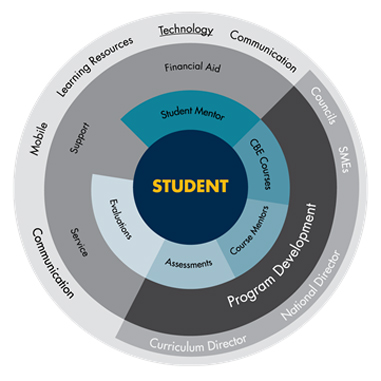

The elements that implement personalized learning at WGU are shown in figure 1, which puts the learner at the center surrounded by rings of support for learning.

Figure 1. The student-centric organization

The student and all support resources needed by the individualized support principle are connected by a comprehensive technological infrastructure, as depicted by the outer ring of the figure. Our description will start with program development and the team used to develop competencies, courses, and assessments. We'll then describe how mentors, evaluators and other learning support is employed.

The measure learning, not time principle requires WGU to advance students at their individual learning rates. WGU assembles related competencies into courses with supportive learning resources. A collection of competencies and one or more assessments form a course. A course may contain many formative assessments to guide learning. Summative assessments measure whether a student has mastered the competencies, and are taken when the student and mentor agree the student is ready.

The competencies are specified by program councils, subject matter experts, national director for the college, and curriculum designers following the employer alignment principle. Assessments are constructed using Robert Mislevy and Michelle Riconscente's evidence-centered design.5 Assessments are designed to be valid and are monitored and maintained by psychometricians who ensure reliability.

Students personalize their learning in each course based on their levels of knowledge and learning preferences. In accordance with the individualized support principle, when students need support, a variety of resources are available. Although students may progress through a course and need no support, each is assigned to an additional faculty member called a course mentor. This subject matter expert is available to the student to answer questions, provide guidance, and help learn the material associated with the competencies. A course mentor is available for individual or group sessions and monitors a learning dashboard to determine whether to reach out to a student who appears to be struggling. Course mentors offer "flipped classroom cohorts," or live events, that suggest the best ways to approach the course and to deal with the most difficult concepts in a course. Student mentors may also recommend any one of the supports in figure 1, depending on a student's need. Mentors coordinate their support through the student relationship management system.

Students receive feedback to help them make efficient and effective learning choices. As mentioned above, mentors use a dashboard that presents the student's likelihood of finishing all courses in a term based on learning analytics, which includes more than a thousand variables (e.g., engagement, assessments taken, successful and unsuccessful patterns, and evaluation data).

The personalized learning plan is generally modified based on formative and summative feedback. Within a course, knowledge checks, pre-assessments, self-assessment, and dialogue with mentors provide indicators of competence that allow each student to skip, survey, or delve into a given course module. Assessments, whether done as objective exams or as essays, videos, or in other media, result in an evaluation and coaching report. A coaching report for an exam provides ratings by competency and guide further learning. Faculty evaluators, a distinct faculty group, provide feedback on performance assessments (projects, essays, papers, etc.) within 72 hours. This feedback includes not only the evaluation results, but also detailed feedback on what was done well and what needs further development.

The no waiting to learn principle means that as soon as a student demonstrates competency through the required assessments, he or she has completed the course and continues forward. At WGU, all courses are offered continuously, with students starting and completing at their own pace. A student completes a program when he or she has completed all courses in the program.

As reported by Complete College America, making full-time progress is vital to student success.6 WGU confirms that full-time, regular and substantive progress is a key to higher graduation rates and uses learning analytics to assess a student's likelihood to complete a full-time load each term. If a student completes at least a full-time load in the first term, they are much more likely than others to graduate and the likelihood increases substantially if a second full-time term is also completed. This predictive measure is based on more than a thousand variables measured during a student's term and appears as a risk indicator on the mentor's dashboard, allowing both course and student mentors to reach out to any student who appears to be at risk. This use of technology not only helps faculty present the right learning at the right time, but also helps students develop their capacity as learners to choose the right learning strategies. The analytics and mentor follow-up allow the appropriate support to be applied to a given situation.

Measuring Success

WGU's use of adaptive learning is expanding in general education and core courses within various programs. Similar to the personalization course findings reported by David Wiley,7 we have found that adaptive learning works best when technology is coupled with appropriate faculty interventions and actions.

WGU uses a number of nontraditional measures to determine the efficacy of the university's model and support structure and publishes them in the WGU 2015 Annual Report.8 Improvements in the number of graduates relative to enrollment growth is one measure: while enrollment has grown over the last five years at 21 percent compounded annually, the cumulative graduate compound annual growth rate is 43 percent for the same time period. The approach has good results for retention. The one-year rate in 2015 was 79 percent, compared to an average one-year retention rate at U.S. public four-year institutions of 74 percent. Students had an overall satisfaction rate in 2015 of 96 percent.

Apart from internal measures, WGU's model compares favorably in engagement, employment outcomes, and graduate well-being. The 2015 National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) polled more than 315,000 students from nearly 600 U.S. and Canadian institutions, finding that students gave WGU scores well above the national average, as shown in table 1.9

Table 1. Comparison of WGU's 2015 NSSE results to national averages

|

WGU |

National |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Acquisition of job-related knowledge and skills |

79% |

69% |

|

Challenged to do their best work |

77% |

60% |

|

Quality of interactions with faculty |

72% |

60% |

|

Quality of academic support |

85% |

73% |

|

Would attend the same institution again |

92% |

82% |

|

Rating of entire educational experience |

93% |

87% |

In a recent Harris Poll survey of 1,255 new college graduates nationwide and 1,144 WGU graduates,10 WGU alumni expressed higher satisfaction with their education (table 2) and have done well in employment (table 3).

Table 2. Satisfaction of WGU graduates

|

Graduate Satisfaction |

WGU |

National |

|---|---|---|

|

Majority of competencies related to work |

80% |

65% |

|

Recommended university to others |

96% |

75% |

|

Satisfied with overall experience |

82% |

69% |

Table 3. Employment outcomes of WGU graduates

|

Employment Outcomes |

WGU |

National |

|---|---|---|

|

Total employed |

94% |

89% |

|

Employed in degree field |

86% |

76% |

|

Employed full time |

86% |

74% |

WGU graduates have demonstrated their ability to apply the competencies they gained through personalized learning. In a 2015 survey by Harris Poll of 305 employers, also reported in the WGU Annual Report 2015:

- 100 percent said that their WGU graduates were prepared for their jobs.

- 98 percent said that WGU graduates meet or exceed expectations; 92 percent said WGU graduates exceed expectations.

- 93 percent rated the job performance of WGU graduates as excellent or very good.

- 94 percent of employers rated the "soft skills" of WGU grads as equal to or better than those of graduates from other institutions.11

WGU has shown by example that a personalized approach to CBE can reduce costs and time to complete a degree while being affordable for the institution. (WGU is self-sustaining on its tuition, with no increase since 2008.) Moreover, WGU has structured personalized, relevant learning that gets out of the way of a student's success, while knowing when and how to support and continuously improve the approach to achieve better outcomes. Though others have found personalized learning to be problematic, especially at scale, WGU demonstrates that an implementation of CBE that employs personalized learning principles — combining faculty interventions and technology — can be successful at scale.

Notes

- New Media Consortium, NMC Horizon Report: 2016 Higher Education Edition (Austin: NMC, 2016): 28.

- "Personalized Learning," [http://postsecondary.gatesfoundation.org/areas-of-focus/personalized-learning/] Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Postsecondary Success website.

- For more on WGU, see John Gravois, "The College For-Profits Should Fear," Washington Monthly (September/October 2011), and "The Unique History of WGU," Western Governors University.

- Sally M. Johnstone and Louis Soares, "Principles For Developing Competency-Based Education Programs," Change 46, no. 2 (March–April 2014): 12–19.

- Robert J. Mislevy and Michelle M. Riconscente, "Evidence-Centered Assessment Design," in Handbook of Test Development, ed. Steven M. Downing and Thomas M. Haladyna (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum): 61–90.

- Complete College America, Time Is the Enemy of Graduation (Washington, DC: Complete College America, 2011).

- David Wiley, "Personalization in Lumen's 'Next Gen' OER Courseware Pilot," iterating towards openness (blog), August 19, 2016.

- Western Governors University, Annual Report 2015 (Salt Lake: WGU, 2016).

- WGU, Annual Report 2015.

- WGU, Annual Report 2015.

- WGU, Annual Report 2015.

Maria Andersen, PhD, is director of Learning Design at Western Governors University. She leads the university's instructional design by creating innovative learning strategies to ensure seamless, intuitive, and engaging curriculum. After years of experience in higher education, Andersen transitioned into the development of learning software by developing educational games for learning algebra. She left higher education to spend three years in the software world, first working for Instructure (Canvas) leading the course designs for a MOOC platform, and then focusing on the design and development of adaptive learning products for Area9 Labs/McGraw Hill Education. Andersen's PhD is in Higher Education Leadership, and she also holds degrees in math, chemistry, business, and biology.

David Leasure, PhD, is provost at Western Governors University and has been involved with online learning since 1995. He has developed online UG, master's, and doctoral degree programs and implemented problem-based online learning. Leasure has advanced degrees in computer science. As associate professor of Computer Science at Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi, he researched technology-assisted learning and teaching with NSF and USDE funding. Prior to WGU he was provost at Colorado Technical University and helped create and shepherd CTU Online.

© 2016 Maria Andersen and David Leasure. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.