Key Takeaways

- Online formative feedback using Google Forms and Sheets combined with FormMule facilitated instant data collection and structured feedback for a course at the University of Colorado Law School to optimize learning outcomes.

- By giving and receiving ongoing, timely feedback, students can practice and modify their behavior during the learning experience, which stimulates motivation and deeper learning.

- Adopting a low- or no-cost approach can make formative feedback easy to implement.

- Investing time and effort to give and receive feedback benefits both instructors and students by providing valuable information to adjust teaching and learning and helps ensure shared goals.

Many instructors approach teaching like baking. Baking requires the perfect assembly of a recipe — the right ingredients in the right quantities combined in the right way. Once you put it in the oven, you hope for the best. Courses, however, can become more successful if we viewed teaching and learning more like cooking and less like baking. Instructors and students are more likely to have a successful and satisfying experience if everyone has the opportunity to taste, offer constructive comments, and adjust the seasonings along the way. Communication provides important feedback to make the dish the best it can be. This is what formative feedback can do for teaching and learning — it can optimize the experience for the instructor and students.

Why Formative Feedback Is Key

Formative feedback is a way for instructors to check in with their students and give and receive timely, constructive feedback. Think of it as a dialogue that can help everyone involved actively contribute to achieving the learning outcomes.

From the start, formative feedback can help ensure that instructors and students are on the same page with regard to course expectations. You can get a sense of where students are with the subject matter, their level of interest and experience, whether they have questions about or concerns with the course syllabus, if they understand the expectations for their participation, how learning will be assessed, etc. All of this may be clear to the instructor, but there will likely be some gaps or areas of confusion for some students, particularly if they're being introduced to a field of study.

Formative feedback can also include "low stakes" assessments so that students can earn some credit for their efforts, but even feedback with no associated point value can prove beneficial. Affording students the opportunity to practice and find out what they could do to improve can reduce anxiety and increase their confidence with "higher stakes" assessments. By identifying their strengths and weaknesses early on, students will gain a better sense that they're on the right track or greater awareness of areas that need more attention. For those students who might be way off course, clear instructor feedback can steer them in the right direction before they're completely lost.

What makes incorporating formative feedback incredibly rewarding is that it can further stimulate motivation and more meaningful learning. When it comes time to formally assess learning, students will find themselves better prepared, and instructors may find that grading is not as demanding.

This also holds true for soliciting course feedback from students. An instructor might think students are following along, but won't know for sure without checking in with them. This feedback can help guide instruction for the remainder of the course and make sure everyone stays on track. The dialogue also helps strengthen the instructor-student relationship because working together demonstrates mutual effort to accomplish the learning goals.

Giving and soliciting feedback doesn't have to be difficult or work intensive as Bill Mooz, scholar in residence at Colorado Law, discovered. Having worked in the tech industry, he had a strong focus on delivering results efficiently and effectively while enhancing the customer experience.

Feedback in a Flipped Classroom

Mooz was tasked with teaching a negotiation skills course for second- and third-year law students and sought my advice in my role at the time as an academic technology consultant serving the Law School at the University of Colorado Boulder. To provide sufficient support for skills development among the 24 students enrolled in the course, he recruited three adjunct instructors who would each rotate in and co-teach with him for three consecutive weeks during the semester. The adjuncts were working professionals whose jobs included negotiating deals, which gave students the opportunity to interact and develop relationships with a network of legal professionals.

Mooz envisioned using a flipped model where students would review PowerPoint lectures with narration prior to class. During class, students would split into four teams of six to practice developing their negotiation skills. He would observe two teams; the co-instructor would observe the other two. He also wanted a way to let the instructors easily and quickly provide feedback to all the students every week, so they could review the comments and focus on improving their skills for the following week's negotiations. Whatever approach we adopted, it needed to be easy to implement, easy for the instructors to learn and use, and beneficial to the students.

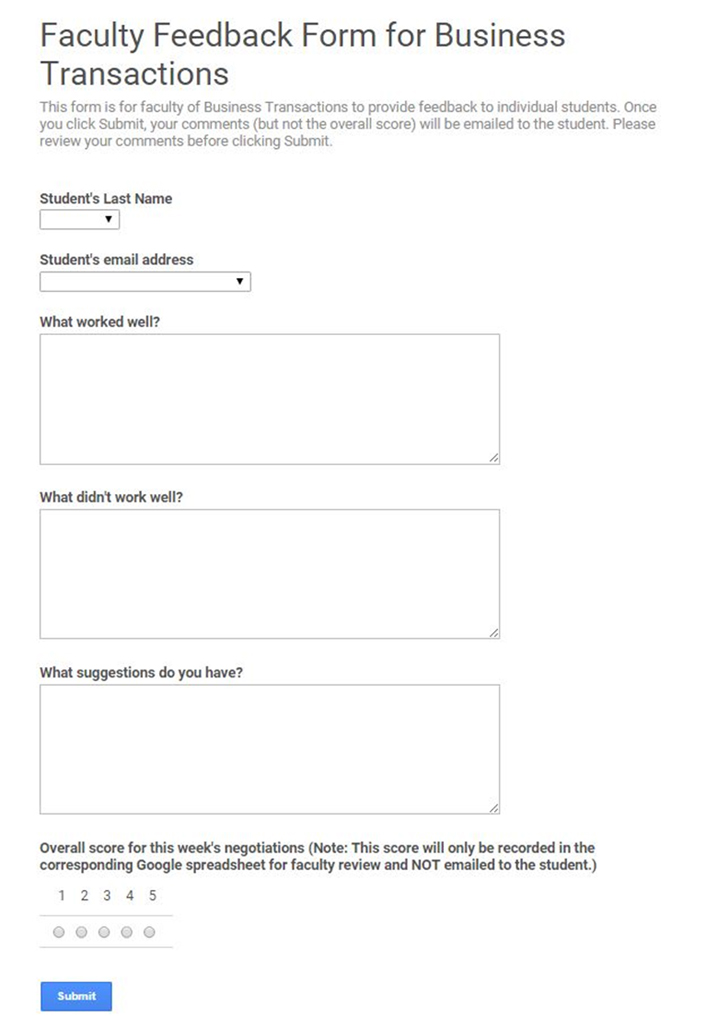

We investigated potential technologies and decided Google Forms would meet the requirements. The form included drop-down menus and comment fields, which made learning how to use the form and entering information simple. Because Mooz would only observe half the class at any time, we had the instructors give a score for the student's negotiations to give him a sense of how each was performing. This score would be kept private and not calculated into the student's overall course grade. See figure 1.

Figure 1. Google faculty feedback form

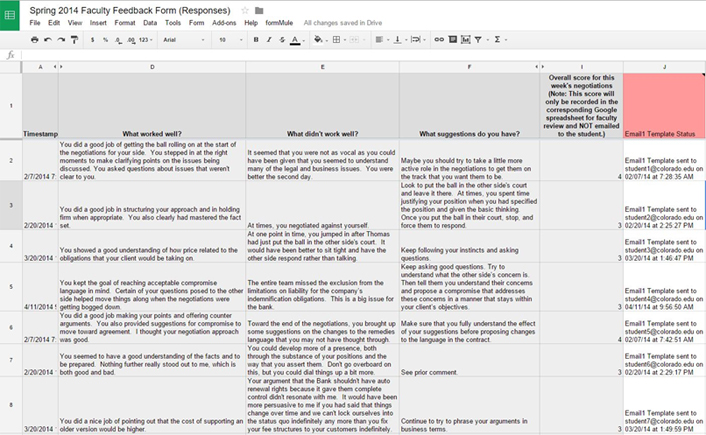

The data the instructors entered would then populate a Google Sheet as soon as they clicked the Submit button. The sheet, accessible only to the instructors, allowed Mooz to easily view the overall class performance and progress, identify trends, and even sort by student to view individual progress.

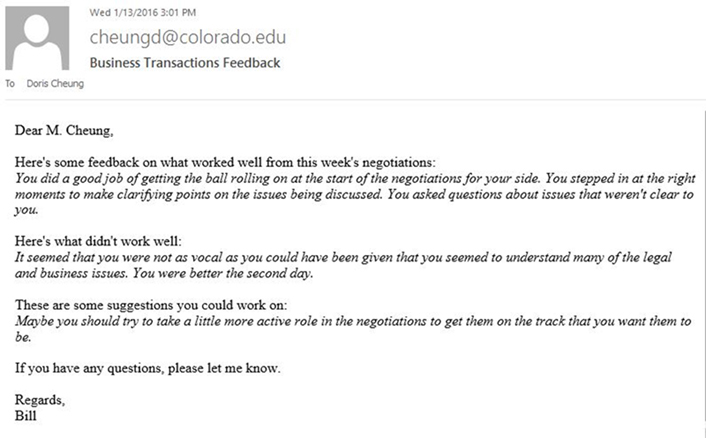

We also wanted to streamline the process for e-mailing the instructors' feedback to the students and accomplished this with FormMule, a third-party e-mail merge utility that works with Google Sheets. We installed and configured it to automatically merge the feedback with an e-mail template and send a personalized e-mail to each student with their instructor's comments. The form and e-mail template were tested and tweaked extensively before course launch. See figure 2.

Figure 2. Sample student feedback e-mail

Once these components were in place, Mooz and I met briefly with the other instructors to walk them through the Google login process and how to use the form. All appreciated the perceived ease of use of the Google Form and were quite enthusiastic to begin teaching.

With the students also being new to Google Forms and Sheets, we included a brief orientation on the first day of class to explain the process and expectations and to make sure students knew how to log in to their Google accounts. Mooz let them know that once the course was under way, the instructors would provide feedback to each student on in-class negotiations.

As instructors completed the form for all of the students they'd observed, comments would compile in the Google Sheet (figure 3). FormMule gave us confirmation of when the e-mail had been sent to each student. As expected, the consolidated feedback provided a running record of the instructors' feedback and straightforward review of the overall performance and weekly progress of individuals and the entire class. The instructors greatly appreciated the convenience and simplicity of using the Google Form.

Figure 3. Google Sheet showing faculty responses to students

This method of providing student feedback worked well, but we did have one small hiccup — a few weeks into the course, one student commented that he had not received any feedback. Once we discovered we had entered an incorrect e-mail address into the Google Form, we quickly rectified the situation, and the student began receiving feedback. We learned that we should have sent a test e-mail to each student at the start of the course and announced that the first feedback e-mails had been sent to ensure timely receipt.

Mooz firmly believes providing students with ongoing feedback is making a difference; the data showed improvement in the students' skills from week to week. What did students think about receiving regular and timely feedback from their instructors? Every semester, Mooz receives positive comments from the students on the process:

"Very, very helpful, thanks Bill. It's unusual to get this kind of detailed feedback in law school and I know it raises some effort on your part to put together, so thank you, I appreciate it and will incorporate your suggestions!"

"Thanks, Bill, I appreciate the feedback. I thought yesterday's negotiations were very productive and I learned a lot of helpful things."

"This morning, I was asked to take the lead to do my first 'real' negotiation at work on a vendor agreement I've been working on with the other side's attorneys, and this class helped me tremendously in moving the negotiation forward."

Mooz, the adjunct instructors, and the students found the feedback forms extremely helpful and the instructors continue to use them for the negotiations course.

Formative Feedback about the Course

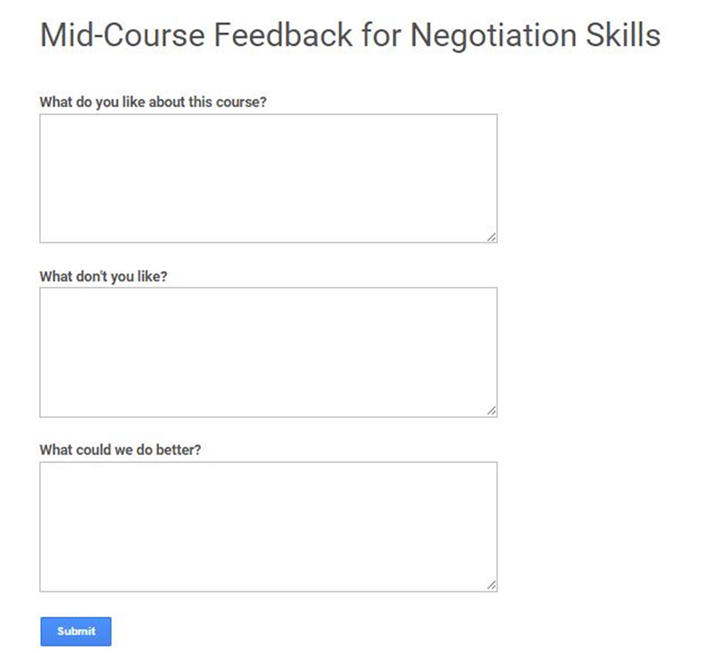

Mid-course, Mooz and I used a similar Google Form to solicit anonymous feedback from the students about the course's strengths and weaknesses to see where we might be able to make improvements. See figure 4.

Figure 4. Mid-course feedback form

We intentionally phrased the third question with "we" to suggest to students the idea of shared responsibility for learning and to reflect on what they could do to make the course better. By asking three simple questions, Mooz was able to identify common themes and concerns, some of which he could address during the remainder of the term. He discussed the comments in general with his students, how he planned to modify his teaching strategies, and how students could contribute to that effort to improve learning. Other comments helped inform him about improvements for future course offerings.

Giving and Receiving Peer Feedback

In the following semester, Mooz experimented with peer feedback, using a student version of the Google Form that asked the following with regard to the negotiations in general:

- What was the most effective aspect of this week's negotiations and why?

- What was the least effective aspect and why?

- What suggestions do you have for the negotiators?

The rationale was that students would likely benefit from reviewing the different comments that their team and the other teams had received and becoming more aware of the qualities that contribute to becoming a better team of negotiators. This approach also emphasized that the course was a collaborative class effort, with everyone learning from each other.

We required students to enter their names on the Google Form to foster professionalism and transparency, and we gave the students view-only access to the Google Sheet, so they could review all student comments from observing team negotiations throughout the semester. All of the feedback was constructive and appropriate. Students became more engaged by having to observe their peers' negotiation skills, and they had an opportunity to learn how to give and receive feedback.

While the experience of giving and receiving peer feedback was worthwhile, Mooz had noticed that as the semester progressed, comments became repetitive and less useful. Rather than spending time coaching the students on how to provide more meaningful feedback, he focused his efforts on improving the students' negotiation skills and elected to phase out peer feedback for subsequent course offerings.

Conclusion

Mooz has incorporated online formative feedback for four semesters now and strongly believes it has made a difference for his students.

Formative feedback benefits both students and instructors by providing valuable information to adjust teaching and learning before it's too late. The idea is really about communicating with students and letting them know how they're doing. It affords students opportunities to practice, get a reality check, and make adjustments, so as to enhance the learning experience and, subsequently, improve learning outcomes.

The use of an online form can facilitate immediate data collection and review of the feedback in a timely manner. As a result, I recommend using Google Forms and Sheets with FormMule1 or other similar low- or no-cost online tools for those interested in incorporating formative feedback into their courses. It can be highly effective for:

- Providing feedback to students during the learning process

- Soliciting feedback from students about how the course is going

- Actively engaging students in learning using reflection and peer feedback

Comparing what it takes to implement online formative feedback with the payoff, it can be an easy sell to instructors designing their courses. Formative feedback works. Taking a little bit of time and effort to give and receive feedback is not only worthwhile, it's good practice for optimizing learning outcomes. It means fewer surprises and, even better, shared success and satisfaction.

Acknowledgment

My sincere gratitude to Bill Mooz, without whom this formative feedback project and article would not have been possible. Your innovative spirit and "This isn't the first cliff I've jumped off of" outlook made collaborating with you fun and rewarding. Thanks, Bill!

Note

- Since our initial implementation, Google has developed a new version of Google Sheets that uses add-ons rather than scripts. Though FormMule is now available as an add-on, our university elected to disable all add-ons, so Mooz continues to use the old Google Sheets with the FormMule script. We don't know how long the old Google Sheets will remain available, but the script has been updated and continues to function. Eventually, we will need to either transition to the new version (if our university decides to enable add-ons) or implement a comparable alternative.

Doris Cheung joined the University of Colorado Boulder in 2006 as an academic technology consultant working with faculty to enhance their teaching, research, and creative works. She is now a learning experience designer collaborating with the campus community to solve high-impact learning problems. In her other life as an educational consultant, Cheung specializes in curriculum and instructional design for online learning. Her teaching experience includes helping others learn how to plan and facilitate learning that makes a difference. She has an MSEd in Adult and Continuing Education and a BS in Community Health Education.

© 2016 Doris Cheung. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC 4.0 license.