Key Takeaways

- When Indiana University adopted a policy for cyber risk mitigation responsibilities, it represented a first step toward understanding and better managing the cybersecurity risk profile of the entire university.

- Known as IT Policy 28, or IT-28 for short, the policy states that IT services should operate from secure facilities (university data centers) and, when practicable, use central IT shared services, as this case study explains.

- However, a successful policy needs to be sufficiently flexible to accommodate services that cannot be run centrally, as long as the service administrator understands, mitigates, and ultimately accepts the risks.

- Other universities should not only consider their university's culture and ability to implement cyber risk policies but also actively prepare for a policy's success by properly provisioning central IT shared services in a reliable, cost-effective manner.

Several universities have had valuable intellectual property breached because of distributed cyber risks at departments and schools outside of the shared services provided by central IT. At one large, public university, valuable data had been exposed and accessed by bad actors for two years before the FBI alerted the university to the intrusion. At other universities, entire schools were taken offline because of deep network-based intrusions.

When Indiana University (IU) adopted a cyber risk mitigation responsibilities policy — known as IT Policy 28, or IT-28 for short — in May 2013, it represented a first step toward understanding and better managing the entire cybersecurity risk profile of the university. The thesis of IT-28 is that IT services should operate from secure facilities (IU data centers) and maximize the use of central IT shared services "to the greatest extent practicable." However, IT-28 also has provisions for considering when specific circumstances necessitate that a particular service can continue to be managed by a local unit.

IT at Universities

IT at universities has generally evolved over many decades to reflect the values of the institutions: highly distributed, decentralized, and within the purview of faculty and other users. The different schools often run their own websites, file servers, and local software systems. Researchers, labs, and administrative units often have their own racks of servers in rehabilitated closets or offices converted to machine rooms, with growing needs for power and cooling. The evolution of technology matches the culture of the academy, except for some "centralized" big systems for administrative use (e.g., Financial, HR, Registration, etc.).

Yet, the risk profile has not followed the culture. A compromised server in one department could create severe legal and financial consequences for the institution. University CIOs generally lack line authority over IT staff and systems in schools and departments, so despite many efforts to educate and inform, no obvious authority exists to ensure IT security vigilance.

Security and IU: IT-28

IU is home to nearly 115,000 students, 9,000 faculty, and 11,000 staff across eight campuses. It is organized as a single university with two research-intensive campuses and six regional campuses, with an annual budget of $3.3 billion. Despite the university's approaches to multi-layered defense, the collective cyber threat surface area is vast. Departments and units must be deliberate about where they store data, ask questions about the security of possible locations, and periodically verify security settings that they assume to be in place. IT-28 is meant to guide them through the process.

IT-28 initially required IU departments and units to perform an extensive self-review. After inventorying unit-level IT systems and services, each created a formal risk assessment and mitigation plan for approval. The process required input, discussion, and analysis by deans, directors, business managers, and IT professionals. In turn, these leaders needed input from their constituents — in other words, contextual understanding of the inherent risks and potential impacts of various mitigation options. Ultimately, IT-28 requires understanding and accepting responsibility for any cyber risks remaining within the department or unit.

In spring 2015, IT-28 completed its first round of reviews and plans. Some faculty and staff voiced concern or outright opposition to the first public draft of IT-28, and in due course IU replicated the approach used in an existing financial practice and policy for mitigating financial risk, deriving an IT policy that balances creative, individual activities with the pressing, collective need to mitigate cyber risk.

The policy is already achieving its primary goal: to reduce the threat surface area of the university's many servers, which are potential targets for bad actors (identity thieves, hackers, and countries looking to steal intellectual property). IU accomplished this by completing one of the first comprehensive inventories of all the distributed servers at a top research university. Was the reduction in risk worth the expense of political capital to help IU stay ahead of cyber threats? The answer was a clear yes: Identification efforts alone led to a 33 percent reduction in the number of servers outside secure, hardened, IU data center facilities.

Factors in IT-28's Success

Surprisingly, IT-28 implementation encountered little pushback in its first year, as noted. Partly that was due to the timing through which the policy was introduced; partly to the policy-driven culture at IU; and partly to the ability to thread the needle with the final precise policy language and processes chosen for implementation. The language and the processes needed to be firm enough to achieve IT-28's purpose yet flexible enough to fit the essential culture of a research-intensive university.

Timing: From Concept to Policy

Leading up to 2012, IU IT leadership had growing concerns that the risks of individual actions and institutional consequences were accelerating, with malicious cyber-attacks becoming more professional and increasingly targeted from all over the world. Independent University Audit staff (not IT staff) revealed a pattern of recurring policy violations in many locally managed servers; these lapses exposed not only that server but also the entire university to risks of sophisticated attacks.

At the time the draft IT-28 policy began to take shape in January 2013, the New York Times and Wall Street Journal announced that Chinese hackers had infiltrated their networks. The next month, the seminal Mandiant report "Advanced Persistent Threat 1" came out, alleging that a division of the Chinese military was hacking U.S. targets. Against this backdrop, presidents, CIOs, and managers across all industries scrambled to reduce cyber risks at their organizations.

IU's departmental IT administrators knew they were ultimately responsible for their units' cybersecurity and wanted to reduce risk, but many just didn't have the training or time in their wide-ranging IT jobs to consistently confront a world of dynamic, escalating cyber risks. IT-28 was designed to give deans and department chairs the information necessary to make informed decisions about the increasingly acute cyber risks in their units.

Shortly after publication of the Mandiant report, the university's central IT leadership recommended that the IT Managers' Council — a group representing IT service professionals from schools and departments across IU — discuss the need for a new policy to expressly address cyber risk. Over the next 90 days, an accelerated effort began to craft a new policy and post it for community comment. Meetings with the president's cabinet, deans, and faculty council at the two largest campuses culminated in a spring town-hall meeting attended by many of the university's IT professionals, staff, and faculty.

Some individuals translated the policy in ways that incited alarm about central IT "taking away faculty research servers." Policymakers opted to "run into the fire" when such concerns arose, offering to meet with faculty as soon as possible. Ten meetings gathered relevant stakeholders across the university. Not everyone warmed to the idea, but all understood the university had to take steps to mitigate the growing cybersecurity risks and agreed to participate constructively.

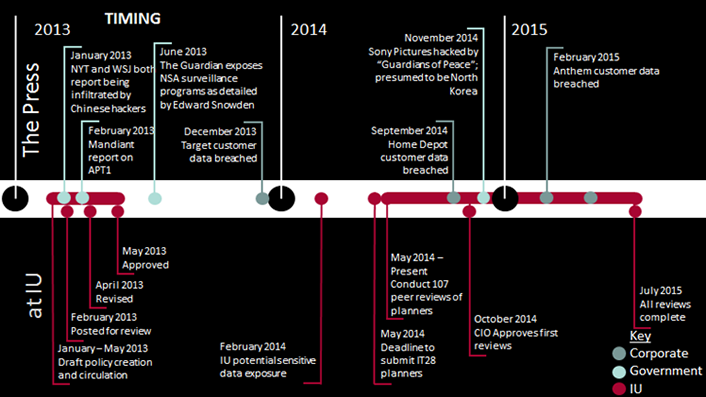

Based on feedback, the development team made revisions to the policy that clarified presumptions and differences for academic and administrative offices. The final policy was approved May 17, 2013. Figure 1 shows the timeline for development and implementation of IT-28, comparing the university's situation to what the press reported in the same time periods.

Figure 1. Timeline for development and implementation of IT-28

The policy first called for a university-wide inventory of all servers within each academic/administrative unit. Without a comprehensive inventory, deans and department chairs might never know about a server under someone's desk, an unsupported or unpatched operating system, or other threats hiding in plain sight. The inventory identified over 5,000 servers at IU — 1,500 more than the University Information Security Office knew existed. Of those, over 700 were located outside secure facilities.

The inventories gave the deans and department chairs their first-ever picture of their individual cyber-threat surface area. Servers would have to remain outside of the secure IU data centers if, for example, they connected to lab equipment that required a direct server connection. However, the deans, department chairs, and their IT professionals identified over 200 servers that they could either migrate to secure facilities or retire from service.

Policy-Driven Culture

The proverb that culture eats strategy for breakfast applies here, as well. IT-28 and its strategies could only be implemented because of IU's existing policy-driven culture. Hundreds of university-wide policies detail everything from what kinds of space heaters are permitted on campus to what information can be sent via e-mail.

The IU trustees' Internal Audit department periodically evaluates departments against a policy or set of policies. However, its capacity is limited, and the department can conduct only a few dozen IT audits each year. If they discover a unit out of compliance with a policy, they document the findings and send the information to the trustees (who meet every two months).

From 2013–2015, IT leadership provided several IT-28 implementation progress updates to the president, deans, and trustees. As the policy neared the two-year mark — the deadline for all reviews — IT leadership presented progress status to a group of deans. The Office of the Vice President for IT had approved 101 out of 107 reviews and would report that to the trustees in a few days. After the meeting, several deans anxiously approached to ask if their units were among the six not yet approved. No one wanted to be the unit out of compliance.

The policy-driven culture at IU is not a given in higher education. Colleagues at peer institutions have expressed appreciation for IT-28 while noting their internal audit departments lack stature and authority. The unfortunate upshot of these conversations? "It's amazing what you've done here at IU, but at [our school], just because it's a policy doesn't mean people will follow it."

Policy Development: Threading the Needle

A cyber risk mitigation policy needs to recognize the needs of both individual units and the university as a whole, balancing the tension in any organization between individual choice and institutional risk. Higher education deans, department chairs, and administrators must balance the demands of senior officers and trustees, who advocate for reducing risk, with the demands of faculty and staff, who advocate for the intellectual freedom to carry out their teaching and research.

IT-28 allows deans to balance the concerns of both sides with the critical phrase "to the greatest extent practicable." The success of the entire policy hung on carefully chosen words: "The primary means of reducing and mitigating Cyber Risks at IU is for units to use the secure facilities, common information technology infrastructure, and services provided by UITS to the greatest extent practicable for achieving their work." A unit could still choose to operate its own IT services if it could warrant sufficient investment in staff time, training, etc. to ensure vigilant cybersecurity. The unit head (usually a dean, department chair, or administrator) would then make a value judgment: Is it feasible to move this server to the data center, or do we require it on premises?

Many unit heads decided against the risk of hosting a service locally, and they could effectively move to a university service or co-locate their server inside the data center. The maturity of virtualized servers and IU's large service offering also eased the transition. Others assessed that the real costs in terms of productivity and dollars would be too severe to use a shared service, so they documented procedures already in place to protect their local services. These choices would eventually be subject to an Internal Audit assessment of IT-28 policy compliance.

In addition to threading the needle with careful phrasing, implementation also drew on two familiar concepts from the university culture: sub-certification and peer review. Both were crucial to gaining acceptance of the principle that cyber risks had to become the visible, formal responsibility of school and departmental leaders.

First, the policy replicated the familiar financial concept of sub-certification. For many years, heads of IU academic/administrative units have had to certify the accuracy of their financial transactions at the end of the fiscal year. The unit leader — typically the dean — then affirms that a checklist of controls and policies have been applied. Finally, the university's chief financial officer reviews and signs off on the statement. The sub-certification warrants the accuracy of the internal controls in a unit. The process gives the CFO, who otherwise has no ability to affirm transactions and controls, a degree of confidence in the integrity of controls and transactions across a highly distributed university.

IT needed a similar process. IT-28 took the concept of financial sub-certification and applied it to cybersecurity: Departments still have purview over their local information technology, but unit leaders have to verify policy adherence. Administrative review then ensures they are being good IT stewards.

After a unit completes an inventory, who decides if local servers and staffing are indeed policy compliant or just a preference? Here, IU replicated the well-known academic concept of peer review. After departments complete their IT inventories, they submit a review to a volunteer panel of IT professionals. Each panel includes three to four reviewers, with at least one member from central IT, one from departmental IT professionals, and one from the IT security office. The panel meets with the unit making the submission and ultimately signs off on their risk mitigation plan.

Considerations for Other Institutions

IU finished its first complete round of IT-28 reviews in the summer of 2015. The policy calls for reviews to continue every two years, beginning the process again. The initial round of reviews focused on hardware, in particular servers. Subsequent reviews may focus on other IT-28 language around using shared services, including content management systems and file storage, already provided by central IT.

Some antecedents that enabled IT-28 at IU provide important context for its success. First, IU invested over $32 million to build its Bloomington data center in 2009. The university has dedicated 11,000 square feet of this data center to housing research systems, including physically co-located servers and virtualized servers. The data center is designed to withstand most natural disasters (including an EF-5 tornado), and the 24/7 operations team constantly monitors systems, servers, and infrastructure to ensure the highest levels of safety and security. Prior to IT-28 adoption, IT staff worked to drive down the cost of using the data center, creating more options for those with limited budgets. Universities that do not have on-premises secure data centers can use cloud services and infrastructure-as-a-service to accomplish most of the same services.

Second, IU's central IT spent many years cultivating a collaborative culture with its department-level IT staff. The initiative, deemed "1IUIT," began building a culture of IT professionals working together for the good of the university several years before IT-28 was proposed.

Other universities should not only consider their university's culture and ability to implement policies but also actively prepare for the policy's success. Before departments and units choose to leverage centralized services, the university needs to properly provision such services in a reliable, cost-effective manner. Even at IU, there was no roadmap for an endeavor of this scale, involving so many parts of the university. The broad cooperation required was achievable due to the long-term success of central IT in serving the needs of the entire university community.

Questions to Ask Before You Begin

To identify considerations for adopting a cyber risk mitigation policy, ask yourself the following questions about the situation at your institution:

-

Could a cyber risk mitigation policy be perceived at your university as a way to force centralization of IT, and how would that affect its successful implementation?

Many universities with a distributed culture of IT decision making probably have easier ways to leverage scale than implementing a comprehensive cyber risk mitigation policy. Adopting such a policy is likely easiest for a university that has already achieved substantial success in implementing shared services.

-

Which process choices in crafting, reviewing, and implementing the policy would be most useful on your campus(es)?

Concepts like peer review and financial sub-certification resonate at most institutions of higher education; would your deans and administrators embrace shifting responsibility for cyber risks to IT, or would they consider increased cyber-independence worth the greater risk?

-

What are the risks to a CIO in pushing for a cyber risk mitigation policy to formalize risk ownership? How should a CIO make that career decision?

Cataloging the risks associated with distributed IT can be perilous to a CIO's career if a university does not have both the means and the will to mitigate those risks. A data breach caused by risks that were known and ignored is potentially career-threatening.

-

If a faculty member at your university had a service that she felt needed an exception to the policy, what arguments could she make? How would your CIO receive these arguments?

IU faculty made arguments for why certain services needed an exception to policy. IT leadership often responded that an exception might require the department to make financial tradeoffs; for example, hiring additional IT staff to ensure a local server is constantly patched, updated, and scanned might mean having to cut funding for post-docs or research stipends. Ultimately, unit leaders (department chairs and deans) have to decide which risks they consider worth taking.

Resources

For more on IT-28 and IU's policy implementation approach:

- IU Knowledge Base overview

- Video of a Lessons from IT-28 [http://meetings.internet2.edu/2015-global-summit/detail/10003685/] presentation at the Internet2 Global Summit

- Campus Technology interview

Dan Calarco is chief of staff in the Office of the Vice President for IT and CIO at Indiana University. He previously served as associate director at Indiana University's Center on American and Global Security. Prior to that, he was co-founder and director of programs for the technology-focused nonprofit One Global Economy. Calarco holds degrees from Brown University and Georgetown University.

Brad Wheeler is vice president of IT and CIO for Indiana University's eight campuses. He is also the interim dean of IU's School of Informatics and Computing. He has co-founded and led collaborations including the Sakai Project, Kuali, the Hathi Trust, and Unizin. Wheeler earned his PhD from IU's Kelley School of Business, where he is also a professor of information systems. He has twice received the CIO 100 award from CIO Magazine, is a recipient of the EDUCAUSE Leadership Award, and was named CTO of the year for 2015 by the Indianapolis Business Journal.

© 2016 Daniel Calarco and Bradley Wheeler. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0 International.