Key Takeaways

- A partnership between Excelsior College and Cengage Learning targets those with some college credits but no degree and not currently enrolled in higher education.

- The CourXam model combines a self-paced digital course with a proctored, college-credit-bearing examination, offered directly to consumers.

- The right balance between instruction and assessment is vital, made somewhat easier because instructors and assessment experts have the same goal — better-educated learners.

- One of the most difficult issues to settle is defining success, which can mean mastery of the subject matter or competency in it.

Tens of millions of Americans have some college credits but no degree and are not currently enrolled in higher education.1 This community has traditionally been the target of credit-by-exam products including Excelsior College's UExcel, the College Board's CLEP, and Prometric's DSST examinations. Such products have been available for over 40 years, acting as an on-ramp for adult students thinking of returning to college to complete a degree. But it is a rare student who can learn entirely new material at the college level using only a textbook and a content guide to the examination to study, prioritize, and absorb the material. With no direct instruction in the subject matter, credit-by-exam's appeal has traditionally been limited to those with prior knowledge or work experience in the subject.

Adult and competency-based education (CBE) have served this non-student community mainly through online certificate and degree programs. But what about individual courses that could support multiple purposes? The Center for Educational Measurement (CEM) at Excelsior College and Cengage Learning recently partnered to begin planning and development of a product called a CourXam, which combines a self-paced digital course with a proctored, college-credit-bearing examination and is powered by Learning Objects, a subsidiary of Cengage Learning. Unlike a college course, CourXams will be available directly to consumers.

The pilot project includes five credit-bearing CourXams in Criminal Justice and five in Business. Cengage instructional designers and content experts work with Excelsior's assessment experts to create each CourXam.

The Instructional Design Philosophy

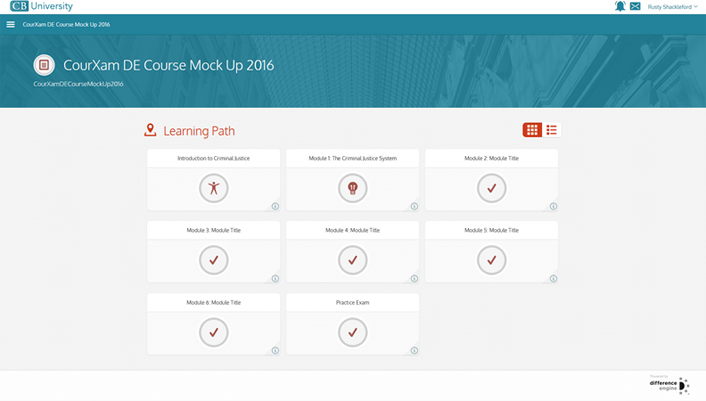

In developing the student study environment, the instructional designers combined diagnostic quizzes, media-rich content, formative assessments with detailed remediation, and a summative practice exam to design a learning path that tailors itself to the learner's needs. Whether the learner is digging into the content for the first time, has been working in a related field for some time, or has previous academic experience, each step in the path directs the them toward clearly delineated learning objectives. Figure 1 shows a mockup of a possible learning path in a Criminal Justice module.

Figure 1. Criminal Justice mockup of a learning path

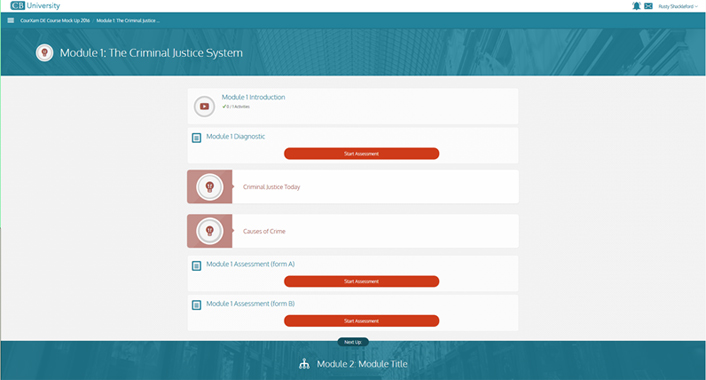

A diagnostic quiz confirms which (if any) of the objectives the learner already has mastered versus what needs further study. A personalized path is created for the learner from the results of that diagnostic. Learning content uses varied text, graphic, video, and interactive forms to ensure multiple cognitive pathways for the learning process. Periodic formative assessments inform learners about their grasp of the content as they proceed through the lessons and modules, and a final, summative practice exam informs the learner of their readiness to take the college-credit-bearing exam or if a review of designated parts of the learning content is needed. Figure 2 shows a mockup of a Criminal Justice module with embedded assessments.

Figure 2. Criminal Justice module with embedded assessments

All design decisions recognized that learners would not be part of a "course" and that no instructor, guide, or peer learners would be available for them. As such, the emphasis went to scaffolding and personalization to help learners assess what they do and don't know, providing feedback to help them focus their efforts where needed.

The Assessment Philosophy

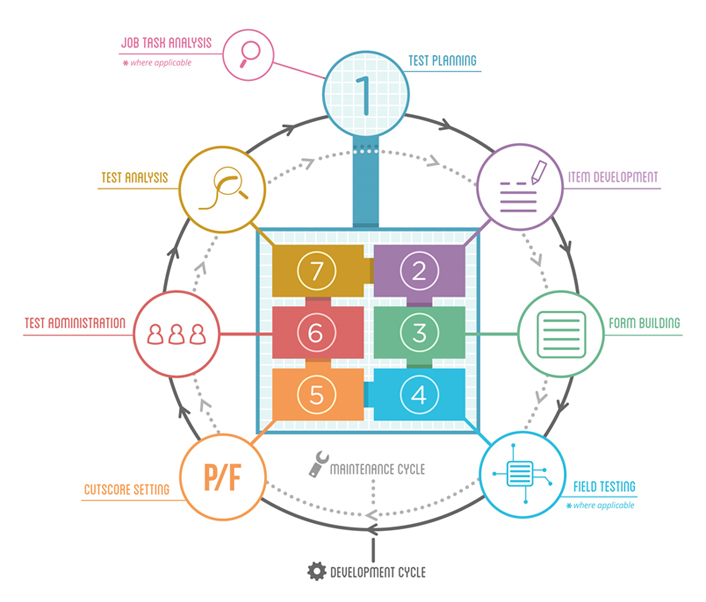

CEM assessment experts approached this project by developing test plan specifications and identifying the material and level of proficiency to test. Then they developed the assessments to meet the plans, following accepted standards for assessment development and quality control, as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Test planning and development cycle

The team designed the test plan in this project to drive not only development of the assessment but also development of the custom instructional design. Like an architectural blueprint for a house, a test plan identifies what needs to be built and how many pieces and substructures are needed, and the assessment developers then act as general contractors to build the pieces and put them together. Assessment developers work with subject-matter experts to write questions (known as items), review them, build them into collections of items (exam forms) that meet the requirements in the specifications, determine the passing scores for each form, and ensure the forms are administered securely. CEM psychometricians then run statistical analyses to ensure the forms and items work properly.

Striking a Balance Between Instruction and Assessment

Most instructors would acknowledge that assessment is a necessary part of teaching and learning; they just don't think highly of educational assessments developed by people who are not hands-on in the classroom. Assessment experts, for their part, often take a dim view of assessments in instructional contexts; they see grades as based on factors other than measurement of learning. Hence the need to find the right balance between instruction and assessment. Ultimately, instructors and assessment experts have the same goal — better-educated learners.

One important component of balance is appropriate separation of the pedagogy and the assessment. If an exam tests knowledge of U.S. history and someone can pass just by remembering an answer pattern, the exam doesn't reveal anything about that person's knowledge of the field. Anyone using the results of that exam to make a decision (determine college acceptance, placement, or credit, for example) can't be certain that the examinees actually achieved the intended learning objectives.2 In large-scale academic assessment of specific subjects, it shouldn't matter at what school the examinee learned the material, who the instructor was, or even whether there was a school or instructor at all. Instead, the assessment should only measure a student's achievement of the stated learning objectives.

In developing CourXams, the design and assessment teams had to determine how to provide instructional design that would align with the areas to be assessed, while guaranteeing that individual assessment items and test forms would remain secure behind a firewall. Joint meetings defined learning objectives in clear, specific, granular, and measurable ways. From these meetings and the shared specification document, both the instructional team and the assessment team could develop their own side of the CourXam. As policy, the items developed for the summative, credit-bearing exam will not be shared with the instructional team, and that exam will be developed and delivered in a separate, live-proctored, secure environment.

The specification process has taught the educators a great deal about assessment and grading and the importance of defining learning objectives. After one such session a participant wrote that the process "provided excellent training that I was able to immediately apply to improve the way in which I approached the development of program and course learning outcomes, curriculum design, and assessment." The assessment team has changed its focus from measuring content areas to which learning objectives apply to breaking down those learning objectives into supporting micro-objectives that are measured explicitly. What Excelsior has learned from this experiment is likely to affect how we develop assessments in the future.

Defining Success

Another interesting challenge arose when the partners discovered that we define success differently — and this difference reflects a major area of debate on CBE. Do we want mastery or a basic level of achievement? If we have properly defined and measured learning objectives, and an examinee demonstrates achievement of those objectives, what should that student's grade be?

If the college credit examination yields only pass/fail grades and the examinee has demonstrated achievement of learning objectives, the answer is easy — the student passes. However, Excelsior College's exam programs use grades of A/B/C/Fail. In our existing process, the achievement of learning objectives is the baseline ("C") below which a student cannot receive credit. Other schools can accept that level of competency in the subject for credit, often a "pass." An examinee who demonstrates learning or understanding beyond the defined learning objectives can earn an "A" or a "B," and the scores that determine those points are based on specific definitions of achievement for each of those levels. Since examinees achieve different scores on exams using the same recommended resource materials, we reason that how much students glean from the materials should determine their success level. Some may simply remember the content, whereas others are able to compare and contrast, draw inferences, or analyze that content better.

The approach differs for instructional designers, who work on building toward the same learning objectives but believe achievement of those objectives, which is how we're defining success, should yield an "A." After all, if we can provide materials that help the student learn all of the learning objectives, what more should it take to reach the A grade? And how can we legitimately expect students to achieve more than is stated in the objectives if we don't provide the instruction and explicit objectives to help them achieve that success?

The difficulty lies in defining separate levels of achievement reflected in separate grades. In standalone assessment, we define the higher levels of achievement in terms of higher Bloom's Taxonomy levels on the totality of objectives and not on the achievement of a subset of the objectives. Assessment in instructional contexts usually works from the top achievement, awarding lower grades to the achievement of something "less than" 100 percent. For example, 75 percent correct answers would yield an unscaled C grade. Unfortunately, the percentage correct does not normally provide sufficient data to validly interpret whether an examinee has met the learning objectives.

The issues raised in this debate are germane to all competency-based-education and assessment. What is implied by "success"? Competency or mastery? And to whom does the distinction matter? Who is the audience for CourXams — the students for whom we strive to accelerate time to completion and reduce the cost of a degree? Their prospective employers, who want to know what they can do? Colleges, for whom the transcripts must impart a clear promise of capability? Accreditors, who seek to improve measurement of student outcomes? Most likely, it is some combination, which is why working to clearly define what success means for this product, and any similar product aimed at an academic market, is so important.

Looking Ahead

By attaching three credit hours to each successful completion of a CourXam, we have the capacity to deliver flexibly managed pathways to a college degree — a vital goal for educators and assessment experts alike, particularly those serving adult, nontraditional, or underserved populations. The challenges we face are a microcosm of the challenges facing higher education everywhere. We look forward to sharing data as CourXams are released to the public and we begin to evaluate results of their use.

Notes

- The Lumina Foundation, "A Stronger Nation: Postsecondary learning builds the talent that helps us rise," 2016; the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey on which the numbers are based was published in 2014.

- For more, read Renee Dudley, "'Massive' Breach Exposes Hundreds of Questions for Upcoming SAT Exams," August 3, 2016.

Nurit Sonnenschein is general manager, Center for Educational Measurement, Excelsior College

© 2016 Nurit Sonnenschein. The text of this article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0.