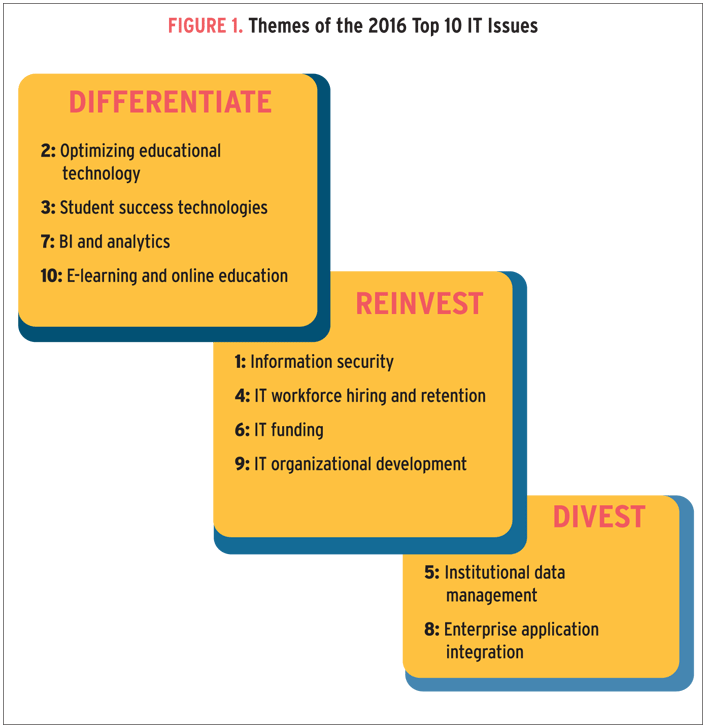

In 2016, higher education IT organizations are divesting themselves of technologies that can be sourced elsewhere and of practices that have become inefficient and are reinvesting to develop the necessary capabilities and resources to use information technology to achieve competitive institutional differentiation in student success, affordability, and teaching and research excellence.

The difficult I'll do right now. The impossible will take a little while.

Information technology in higher education has never been easy to manage, but these days doing so seems like a choice between the merely difficult and the impossible. That is partly because so much is changing so quickly—technology and higher education, opportunities and expectations, requirements and funding—and partly because we are trying to apply existing methods to new problems. Imagine driving a car in the first years of automobiles. There were roads, certainly. But they were narrow and rough and had been built for different, previous kinds of vehicles and traffic. The necessary fuel sources were hard to find, and the rules of the road that worked for wagons and carriages frustrated car drivers. Early drivers were inexperienced, of course. The existing infrastructure thus limited the potential of the new automobiles. In many ways, colleges and universities are similarly expecting the existing ecosystem—their people, processes, and culture—to be able to support, without change, today's new and very different technologies.

How can we align our timelines and change our ecosystem? The 2016 EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues1 offer a clear response: divest, reinvest, and differentiate. As will be explained below, the ten issues divide into these three categories (see figure 1). Higher education IT organizations are divesting themselves of technologies that can be sourced elsewhere and of practices that have become inefficient and are reinvesting to develop the necessary capabilities and resources to use information technology to achieve competitive institutional differentiation in student success, affordability, and teaching and research excellence.

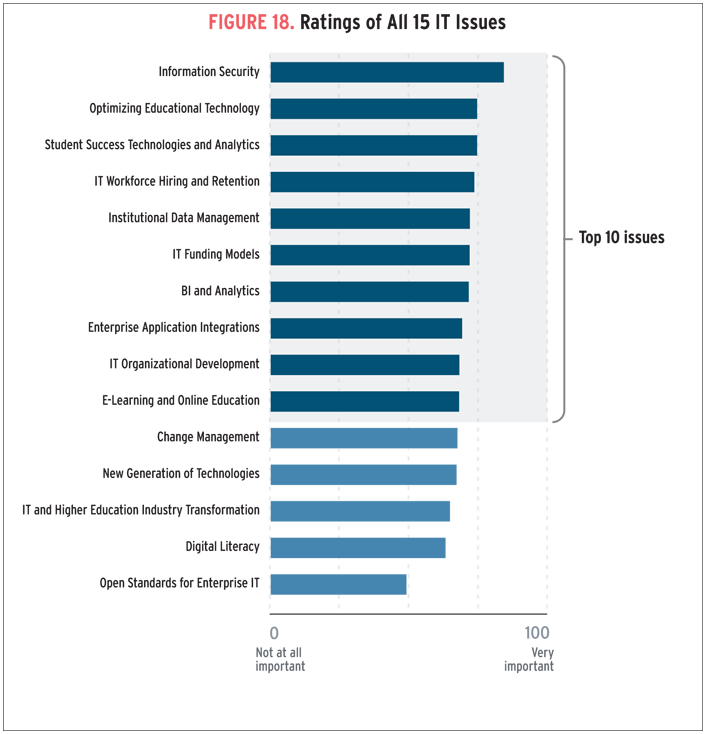

Top 10 IT Issues, 2016

- Information Security: Developing a holistic, agile approach to information security to create a secure network, develop security policies, and reduce institutional exposure to information security threats

- Optimizing Educational Technology: Collaborating with faculty and academic leadership to understand and support innovations and changes in education and to optimize the use of technology in teaching and learning, including understanding the appropriate level of technology to use

- Student Success Technologies: Improving student outcomes through an institutional approach that strategically leverages technology

- IT Workforce Hiring and Retention: Ensuring adequate staffing capacity and staff retention as budgets shrink or remain flat and as external competition grows

- Institutional Data Management: Improving the management of institutional data through data standards, integration, protection, and governance

- IT Funding Models: Developing IT funding models that sustain core services, support innovation, and facilitate growth

- BI and Analytics: Developing effective methods for business intelligence, reporting, and analytics to ensure they are relevant to institutional priorities and decision making and can be easily accessed and used by administrators, faculty, and students

- Enterprise Application Integrations: Integrating enterprise applications and services to deliver systems, services, processes, and analytics that are scalable and constituent centered

- IT Organizational Development: Creating IT organizational structures, staff roles, and staff development strategies that are flexible enough to support innovation and accommodate ongoing changes in higher education, IT service delivery, technology, and analytics

- E-Learning and Online Education: Providing scalable and well-resourced e-learning services, facilities, and staff to support increased access to and expansion of online education

The EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues website offers the following resources:

- A video summary of the Top 10 IT issues

- Recommended readings and EDUCAUSE resources for each of the Top 10 IT issues

- An interactive graphic depicting year-to-year trends

- IT Issues lists by institutional type

- The Top 10 IT Issues presentation at the EDUCAUSE 2015 Annual Conference

Divest

The only way to move higher education's people, processes, and culture into the developing future is by moving away from methods whose effectiveness is waning and by adopting practices that better fit that new world. Reform is insufficient, because it optimizes today's practices in lieu of developing tomorrow's. To make room for a new set of practices—a new infrastructure—we need to divest ourselves of today's practices. Higher education institutions are doing just that, with 58 percent of them reporting that business process redesign (not optimization) is a major influence on their IT strategy.2

Divestment also extends to technologies and services. Many colleges and universities have moved or are moving beyond the question of whether to run their own infrastructure and applications in the presence of reliable, effective, and up-to-date external solutions; IT organizations are reengineering and resourcing their systems and services. Moving from historical services onto emerging platforms is a major part of IT strategy at six in ten (61%) colleges and universities, and shared services is a major part of IT strategy for over half (54%).3 Two of this year's Top 10 IT Issues focus on this divestment challenge:

Issue #5. Institutional Data Management

Issue #8. Enterprise Application Integrations

IT as a Service

How can institutions divest effectively to address both of these issues? IT as a Service is a model for running the IT organization more like a business—one that has to compete with alternative providers—and less like a cost center. The model focuses the IT organization on efficiency and transparency to contain and clarify costs and on service and agility to best meet the changing needs of the institutional community. IT as a Service includes methods to help IT organizations achieve a balance of efficiency and excellence.

Standardization and simplification are core principles of IT as a Service. Complexity kills efficiency. Copious, distributed, and disjointed, today's higher education's enterprise applications exemplify unintentional complexity. That complexity resulted from optimizing departmental authority and decision making. Now higher education needs applications and systems that can cost-effectively share data and processes to support services and analytics. Well-engineered systems integrations can meet current and future needs efficiently.

Systems integrations include data integrations, which require data governance and management and can address multiple objectives: developing effective analytics while reducing costs and risk. Data needs to be standardized and integrated to lay the groundwork for cost-effective, scalable, and valid analytics. Standards and integration are almost impossible to achieve without an institutional commitment to data governance. Using data in broader and more consequential ways increases its exposure and the potential impact of data breaches, making data protection more important than ever.

Reinvest

Divestment alone addresses only part of today's challenge. IT organizations need to lay the groundwork for using information technology to deliver meaningful value to higher education. They need to develop funding models that focus on information technology as an investment instead of a cost, and they need to reinvest in their people (the organization's most important asset) and information security approaches. Reinvestment is a theme of four of the 2016 Top 10 IT Issues:

Issue #1. Information Security

Issue #4. IT Workforce Hiring and Retention

Issue #6. IT Funding Models

Issue #9. IT Organizational Development

Feeling Insecure

Information security is the top issue for 2016, by a significant margin.4 Our understanding of information security has deepened as the security ecosystem has advanced. Addressing the challenge of information security encompasses technical controls, policies, outreach and education, and risk management. The EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel was clear that institutions need to constantly respond to changing circumstances and need to consider information security holistically rather than responding separately to each new threat, security layer, or component.

People

The changes under way are most disruptive to those in the IT workforce—those who must also design and implement the changes. IT organizations are shifting as surely as IT services and infrastructure. Many current roles are becoming obsolete, to be replaced by new roles.5 Adapting both the workforce and the organization will require special skills of CIOs and IT managers and will place more emphasis on the partnership between the human resources (HR) and IT organizations. Yet organizational change is not the only workforce challenge for CIOs: many institutions are reducing budgets and benefits or flat-lining compensation at a time when new IT hires are essential to fulfilling institutional objectives, and an improved job market for IT professionals may make it hard to keep existing and prospective staff.

Follow the Money

Funding continues its unbroken streak of achieving a place in the EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues list every year. The funding challenge remains unchanged from the previous two years: how to fund ongoing operations, growth in demand, and institutional innovation.

Panel members emphasized that to contain the IT budget, institutions need to introduce an ongoing discipline of continual divestment, replacing outdated foundations (services, processes, and technologies), and of continual reinvestment, ensuring that the IT workforce is agile and adaptable and that risks like information security are well-managed.6

Differentiate

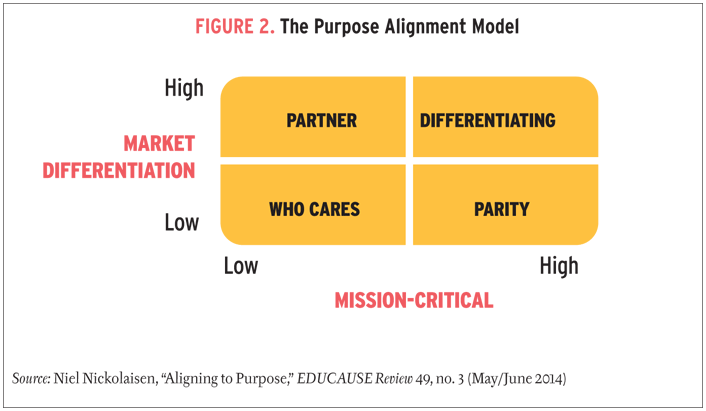

The term special snowflakes has been used to describe institutions or departments that can't standardize or collaborate because they do things their own way.7 To achieve value, IT organizations must distinguish between difference and differentiation. Niel Nickolaisen's Purpose Alignment Model (see figure 2) provides a framework for understanding when variability is meaningless and when variability adds value.8 On the bottom half of the model, services with low market differentiation are good candidates for the most efficient yet effective solutions (for mission-critical needs like payroll or e-mail), the very lowest cost solutions, or even divestment (for needs that may no longer be relevant). Needs that are not mission-critical but are differentiating are uncommon (the model's top-left quadrant); when they exist, they provide opportunities to partner or share services to contain costs.

A few mission-critical services can also create market differentiation (the top-right quadrant). They provide opportunities to use information technology for a competitive advantage. In Nickolaisen's words, "These differentiating activities are the few things—somewhere between one and three in number—that we must do better than anyone else. They deserve our innovation and creativity because these are the things that create our competitive advantage, our unique value proposition." It is these genuinely special activities that the IT organization and the institution should invest in, not simply pay for. Differentiating activities will vary from institution to institution, however. Even when many institutions have the same differentiating activity, they will mold their solutions to reflect meaningful differences in mission, values, and constituents. E-learning, student success technologies, and analytics are priorities for many institutions,9 and they can and should be designed to strengthen and extend each institution's unique value to the higher education marketplace.10

Four of this year's Top 10 IT Issues reflect higher education's efforts to use information technology to differentiate:

Issue #2. Optimizing Educational Technology

Issue #3. Student Success Technologies

Issue #7. BI and Analytics

Issue #10. E-Learning and Online Education

Where to Differentiate

James Hilton, University Librarian and Dean of Libraries and Vice Provost for Digital Education and Innovation at the University of Michigan, has predicted: "The multivariant pressure on higher education going forward—over the next five years and beyond—is going to be to get better at telling a story that embraces differentiation."11 Information technology can help. Information technology has begun to deliver services that can be directly mapped to higher education's most strategic priorities, including student success, affordability, excellence in research and teaching, and analytics. Integrated student planning and advising systems contribute measurably to student success. Institutions are starting to accrue cost savings from standardization and outsourcing. Research not only benefits from technology; it depends on it. We seem finally to have entered an era in which technology-supported education is fulfilling its aspirations to improve pedagogy and learning and to expand access to all types of underserved populations. And the use of analytics is enabling institutions to make more timely intelligent decisions to benefit themselves and individual members of their communities. These are examples of potentially differentiating activities that institutions identify as priorities that they "must do better than anyone else."

How to Differentiate

These differentiating activities are innovations that require new investments. Innovation is an inherently inefficient process: close to 90 percent of innovations fail.12 A financially beleaguered institution under intense scrutiny from a governing board and perhaps also a state legislature may have little appetite for spending money and for making bets with long odds.

Divestment and reinvestment are foundations upon which differentiation depends. Divestment paves the way for differentiation by developing the IT organization's ability to operate efficiently; the organization can institute needed simplifications, integrations, and new processes, and by achieving savings in one area, it can deploy those savings in another area to support differentiation. Reinvestment strengthens the organizational and technical foundations on which successful innovation depends.

Collectively, the Top 10 IT Issues represent enormous change, challenge, and promise. Though each deserves separate consideration, they are inseparable.

2016 EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel Members

|

Name |

Title |

University |

|---|---|---|

|

Gerard W. Au |

Associate Vice President, Information Technology Services |

California State University, San Bernardino |

|

Michael Bourque |

Vice President, Information Technology Services |

Boston College |

|

Jonathan Brennan |

Chief Information Officer |

SUNY College of Technology at Delhi |

|

Karin Moyano Camihort |

Dean of Online Programs and Academic Initiatives |

Holyoke Community College |

|

Timothy M. Chester |

Vice President for Information Technology |

University of Georgia |

|

Keelan Cleary |

Director of Infrastructure and Enterprise Services |

Marylhurst University |

|

Andrea Deau |

Information Technology Director |

University of Wisconsin Extension |

|

Cory F. Falldine |

Chief Information Officer |

Emporia State University |

|

Patrick J. Feehan |

Information Security and Data Privacy Director |

Montgomery College |

|

Dwight Fischer |

Assistant Vice President and CIO |

Dalhousie University |

|

Craig A. Fowler |

Chief Information Officer |

Western Carolina University |

|

Darcy A. Janzen |

E-Learning Support Manager |

University of Washington Tacoma |

|

Jim Jones |

Interim Chief Information Officer |

Gonzaga University |

|

Brad Judy |

Director of Information Security |

University of Colorado System |

|

Kirk Kelly |

Associate Vice President and CIO |

Portland State University |

|

Deborah Keyek-Franssen |

AVP, Digital Education and Engagement |

University of Colorado System |

|

John C. Meerts |

Vice President for Finance and Administration |

Wesleyan University |

|

Celeste M. Schwartz |

Vice President for Information Technology and College Services |

Montgomery County Community College |

|

William R. Senter |

Chief Technology Officer |

Texas Lutheran University |

|

David Starrett |

Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs |

Columbia College |

|

Gordon Wishon |

Chief Information Officer |

Arizona State University |

The EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel comprises individuals from EDUCAUSE member institutions to provide feedback to EDUCAUSE on current issues, problems, and proposals across higher education information technology. Panel members are recruited from a randomly drawn and statistically valid sample to represent the EDUCAUSE membership.

Top 10 Strategic Technologies

The EDUCAUSE IT Issues research is complemented by Higher Education's Top 10 Strategic Technologies for 2016 from the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR). The strategic technology reports provide a snapshot of the relatively new technological investments on which colleges and universities will be spending the most time implementing, planning, and tracking, as well as the trends that influence IT directions in higher education. Together, the trends and forecasts reported in the Top 10 IT Issues and Strategic Technologies research help IT professionals enhance decision making by understanding what's important and where to focus.

Issue #1: Information Security

Developing a holistic, agile approach to information security to create a secure network, develop security policies, and reduce institutional exposure to information security threats

"The expectations and needs of the user community at an institution of higher education are wide-ranging and fast-changing—agility in our delivery of technology-based solutions and services is key. But, without appropriate security measures, any open and agile solution lessens in value."

—Michael Bourque, Vice President, Information Technology Services, Boston College

Across the entire spectrum of higher education missions—from teaching and learning to business operations to community outreach to innovation and discovery—we rely on technology that is constantly under threat. Protecting the institution from the myriad of security threats is a fundamental challenge for IT leadership. Information security has evolved from a largely technical field to one that encompasses not only technology but also risk-management practices, user training and education, and business acumen. With information security now acknowledged as a field in which "perfection isn't nearly good enough," one security incident can ruin an IT leader's day(s), expose confidential data of users or the institution, lead to significant out-of-pocket costs connected with responding to the incident, and diminish an institution's reputation and consumer confidence. A bad day indeed.

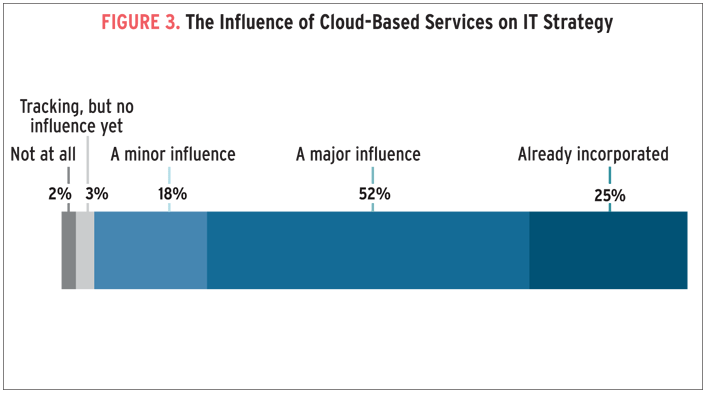

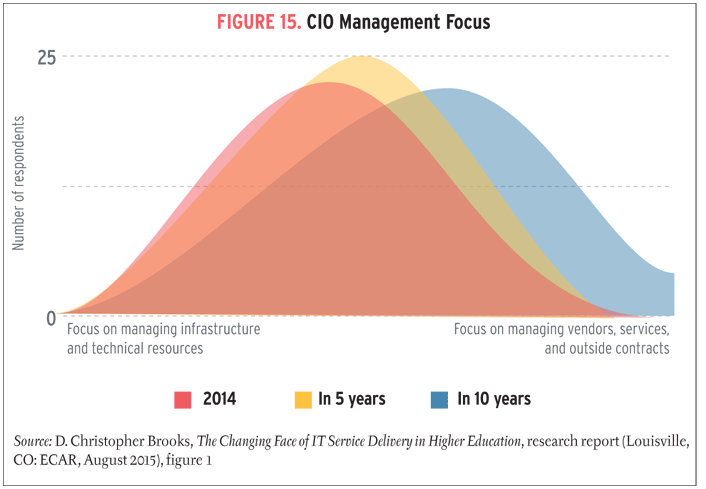

Against this backdrop of constant threats is a higher education technology environment where the expectations and needs of the user community are wide-ranging and fast-changing. IT leaders anticipate that the time currently spent managing infrastructure and technical resources will shift to time spent managing services, vendors, and contracts.13 Agility in the delivery of technology-based solutions and services is key—especially with the fast-paced adoption of cloud-based services (see figure 3). Services and solutions need to be architected so that they can be introduced, modified, and even retired in rapid fashion.

Without appropriate security measures, however, any open and agile solution lessens in value. Higher education is challenged to quickly design and build systems that include proper safeguards for reliability and security. This challenge is further exacerbated by the changing nature of IT service delivery and the move toward the cloud. Even though the number of institutional security and privacy professionals is increasing because of the changed nature of service delivery,14 the central IT organization is still perceived as being slow to review and approve the implementation of cloud and other outsourced services. If the central IT organization cannot be agile enough in its review and implementation of cloud services, the path of least resistance for users may be to go it alone, without institutional IT involvement. In those instances, it is also entirely likely that the path of least resistance may not include effective security safeguards and that users may unwittingly put institutional and/or individual data at risk.15

The truth is that institutional information security is everyone's job. Recent news reports of high-profile data breaches have highlighted that organizational approaches to information security must be holistic, agile, and comprehensive. No longer content to merely "secure the perimeter," institutional approaches must encompass technical safeguards (i.e., those approaches implemented in technology solutions) and administrative safeguards (i.e., those approaches implemented in institutional policies), in order to be effective. Due to its unique mission and cultural need for transparency and openness, higher education has long adopted multifaceted information security approaches:

- 96 percent of institutions have an institutional IT acceptable use policy.16

- 92 percent of institutions have deployed malware protection technologies.

- 90 percent of institutions have deployed secure remote-access technologies.

- 78 percent of U.S. institutions have conducted some sort of IT security risk assessment.

- 71 percent of U.S. institutions have mandatory faculty/staff training on information security.17

Even with these numbers, institutions still have much work to do to secure networks, systems, and applications; develop security policies (only 27% of U.S. institutions have an information security policy that is fully approved by leadership);18 educate campus IT users; and reduce institutional exposure to information security threats. Recent news reports of data breaches provide IT leaders with a springboard to launch discussions with institutional leaders about improving campus information security.

Information security can be a daunting topic for IT departments with limited resources: managing security effectively is not free. So there must be buy-in from the executive level to secure funding and create enforceable policies. All institutional departments and all users of IT resources (students, faculty, and staff) must understand and promote good information security practices to protect institutional data. Making modest institutional improvements in information security posture can give institutions and their IT departments the confidence to tackle the more challenging information security tasks that will inevitably arise as service-delivery approaches evolve.

Advice

- Create comprehensible and enforceable information security policies. Make sure that these policies are understandable and actionable by all community members, and post them conspicuously.

- Develop a comprehensive approach that addresses the information security concerns of mobile, cloud, and digital resources. The changing nature of service delivery is inevitable, and institutional leaders must develop strategies for handling an environment in which institutional data and services are located on third-party resources and are accessed by computing devices not owned or controlled by the institution.

- Develop a training framework for information security awareness to educate all members of the campus community about threats and how to take action to protect institutional data. The training framework should include initial training and ongoing educational opportunities.

- Continue to engage in proactive information security activities that adopt a defense-in-depth approach. Use scanning tools to identify and respond to system vulnerabilities; actively and aggressively identify and block malicious activity; implement reliable identity-management technologies; perform penetration testing and act on the results; collect logs and monitor for suspicious or concerning events; and back up critical institutional data and make sure data can be restored from those backups. Do not rely on a single control.

- Participate in organizations that work together to improve higher education information security. Organizations such as EDUCAUSE, Internet2, and the Research and Education Networking Information Sharing and Analysis Center (REN-ISAC) provide opportunities to improve understanding about information security practices in higher education, develop higher education information security professionals, and collectively respond to information security threats.

- Provide the institution's governing board with an annual IT security risk update, which can greatly help board members as they assess and govern the institution's overall enterprise risk assessment.

- Use the EDUCAUSE Information Security Maturity Index and the HEISC (Higher Education Information Security Council) Information Security Program Assessment Tool evaluate the institution's current state of information security.

Issue #2: Optimizing Educational Technology

Collaborating with faculty and academic leadership to understand and support innovations and changes in education and to optimize the use of technology in teaching and learning, including understanding the appropriate level of technology to use

"As the availability of technology grows on our campuses, virtualizing and extending the campus environment and the faculty-student interaction becomes central."

—Karin Moyano Camihort, Dean of Online Programs and Academic Initiatives, Holyoke Community College

Today's collegiate classroom and pedagogy look very different from those of ten years ago.19 Almost every institution is supporting a set of core educational technologies (e.g., LMS, technology-enhanced spaces, hybrid/blended courses), and most faculty are adopting them.20

Innovation comes in response to concrete problems. To find the most useful educational technology innovations, we should give thought to the issues and challenges that technology could help us address. For example, technology provides real opportunities to enhance both faculty-student and student-student interactions and to virtualize and extend the campus environment:

- Faculty-student interactions. Most current interactions outside the physical or digital classroom are asynchronous, via LMS or e-mail. However, students appreciate having their questions answered by instructors in real time. Holding virtual online office hours can create a number of benefits: meetings can take place at convenient times, and relevant discussions can be archived and shared with the entire class.

- Student-student interactions. Students who have the opportunity to communicate and work with each other become more effective and successful learners. According to the Pew Research Center, 92 percent of teens report going online daily, including 24 percent who say they go online "almost constantly."21 Providing tools, training, and guidelines to reinforce formal and informal student-to-student interaction is a vital part of virtualizing the campus experience.

- Student–campus environment interactions. Today's students live in a digital environment that needs to be embraced to effectively engage students and prepare them for the future. Technologies such as gaming, simulations, open educational resources (OERs), and courseware are transforming the way faculty teach, the way students learn, and how the two groups interact with each other. New technologies such as alerts and pathways are also transforming other administrative and academic areas like advising and planning. Not all technologies translate well from personal to academic use: for example, students use social media extensively in their personal lives, but a growing majority prefer to keep their academic and social lives separate.22

The impact of these and other teaching and learning technologies needs to be assessed and shared to ensure that educational technology is truly effective and continues to flourish and evolve. Optimizing educational technology isn't actually about the technology. It's about understanding and working within the complex system in which postsecondary learning and teaching take place. It's about understanding learning objectives from the macro (institutional, disciplinary) to the micro (course, module, class period) level. It's about understanding what facilitates learning: strengthening and leveraging relationships (among faculty, students, and advisors), delivering relevant and engaging content, supporting active student learning, and helping students understand and focus on priorities.

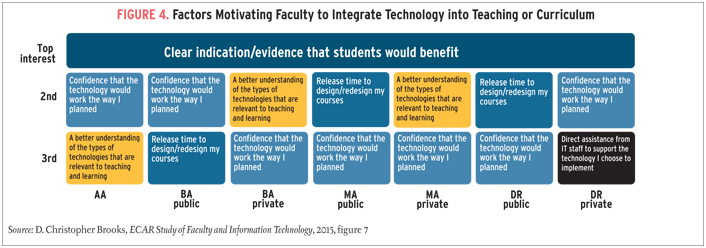

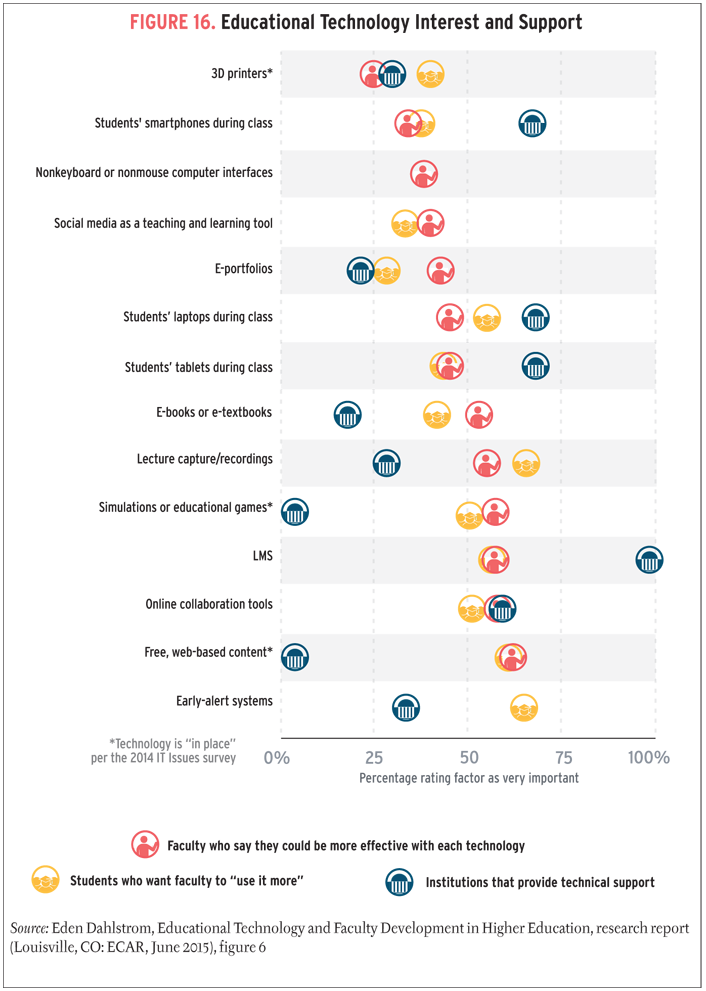

Optimizing educational technology is also about understanding how faculty on a particular campus are, or aren't, rewarded for delivering excellent teaching and services, partnerships, and support—and also how they are motivated to do so. The most important motivator for faculty is clear indication or evidence that students benefit from technology. Faculty also want help with incorporating technology into their courses (see figure 4).23

Technology has many faculty at hello but loses them soon after. Trying a new technology in the learning environment is easy. It is much less easy for faculty to accurately and easily recognize how effectively the tool is working, whether learning is being enhanced, and whether and how to modify the use of the tools to make them more effective. Without evidence of impact, the majority of faculty will not be motivated to incorporate new technologies into their teaching. Without support, many will struggle to do so, even if they are motivated. Instructional design support can be an important component of optimizing the appropriate level of technology to use.

The evaluation of technology-based instructional innovations is

- a major part of IT strategy at 44% of institutions,

- a minor influence on IT strategy at 34% of institutions, and

- not considered at all at 19% of institutions.

—Susan Grajek, Trend Watch 2016 (ECAR, forthcoming)

Finally, increasing use of technology is not always the best way to improve teaching and learning. Students have made it clear that technology-enhanced learning is appealing. However, technology-dominated learning in the form of fully online courses is not: 61 percent of students say they learn best in courses with some online components, 18 percent prefer mostly online courses, and only 9 percent learn best in fully online courses.24 Different levels and applications of technology are appropriate for different institutional missions, individual faculty, and individual learners. Ideally, learners will find the faculty and institutions that best fit them, and institutions and faculty will help students make those choices. IT leaders' roles are to help raise awareness of the possibilities and to execute with excellence. Academic leaders and instructors, not IT professionals, should determine the pedagogical and mission-driven priorities. Most effective is when all stakeholders—IT leaders, academics, advisors, and students—collaborate on solutions.

Advice

- Implement practices (don't start with technologies) that strengthen relationships: faculty to student, student to student, faculty to faculty. Secure collective acknowledgment that (a) strengthening relationships leads to learning, (b) certain practices strengthen relationships, and (c) certain technology tools can facilitate those practices.

- Consider how faculty curate and create relevant content (and partner with libraries for this). Then, make it easier for them to curate, create, and provide access to that content through the use of OERs, videos, simulations, and other resources. Secure collective acknowledgment that (a) relevant content leads to and supports learning, (b) certain processes are involved with curating and creating that content, and (c) certain technology tools, services, and support can facilitate those processes.

- Promote active involvement by students in and out of the classroom. Understand how the brain works (e.g., using 10-minute chunks in lectures) and how to encourage student reflection. Secure collective acknowledgment that (a) active involvement of students promotes learning, (b) certain practices strengthen active involvement, and (c) certain technology tools can facilitate those practices.

- Keep students on-task/invested/engaged/persisting. Secure collective acknowledgment that (a) engaged, persistent students are more likely to be students who learn (and complete), (b) certain practices strengthen engagement and persistence, and (c) certain technology tools can facilitate those practices.

- Partner with other service units, faculty affairs, and administration to

- define (learning objectives) or inventory (practices for strengthening learning relationships/community, curating and creating relevant content, promoting active learning, promoting student engagement and persistence);

- probe for ideas for new practices;

- link existing practices to current and desired tools, services, support; and

- pilot and evaluate new tools and services, which might be different by discipline. Be careful not to overpilot (i.e., introduce too many different solutions) so that you can drive for a (hopefully flexible) standard offering.

- Tap into existing expertise in the faculty ranks, using effective practitioners as role models and facilitators.

- Provide appropriate and effective instructional design support and resources to maximize opportunities for effective use of technologies.

- Develop ways in which faculty and students can share their experiences with one another and showcase innovative uses to campus stakeholders and leadership.

Issue #3: Student Success Technologies

Improving student outcomes through an institutional approach that strategically leverages technology

"Institutions must be able to generate the appropriate alerts for their students, and if institutions can't participate in tweaking algorithms that might be proprietary to a vendor, that's a red flag for me. More important, institutions benefit from having a full understanding of which interventions will take place across any number of student service or academic units, how those will be communicated across those units, and how they will be judged for effectiveness."

—Deborah Keyek-Franssen, AVP, Digital Education and Engagement, University of Colorado System

Student success technologies involve the use of data collection and analysis tools at all levels to predict student success or risk, alert those who can intervene, and assess the effectiveness of those interventions. Student success technologies can be broken into three categories: (1) tools that support advising and other student services, (2) tools that support teaching and learning, and (3) tools that inform curricular design and institutional priorities.

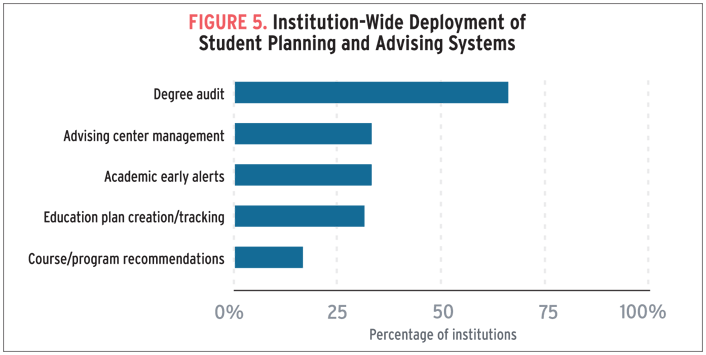

In the first area—advising and student support services—there has been interest over the past few years in the redesign of the advising process and the inclusion of early-alert technologies that provide opportunities for faculty and advisors to send manual alerts or to trigger automated alerts providing students with reasons for the alert, recommendations, and next steps. Student academic planning tools are also available at many institutions. Some institutions require each student to have an educational plan, which facilitates a more in-depth conversation with advisors and provides the institution with data to develop an academic course schedule that aligns with students' plans (see figure 5).

In the second area—teaching and learning—technologies that support student engagement and that provide students and faculty with learning analytics are being used to improve student outcomes. While technologies are being developed and enhanced to support student success, the institutional processes and usage of the tools contribute more to improvement than do the technologies themselves.

Finally, analytics also plays a major role in the third area: curricular design and institutional priority-setting. Metadata about student swirl—in and out of majors, in and out of courses, and in and out of institutions—can and should inform curricular design, academic programming, and even faculty assignment or development. It can also identify different pathways for students through a degree program. In addition, many student success technologies support interactions between the students and the institution.

Students are conceptually interested in having their instructors receive feedback about their performance: 59 percent are extremely or very interested, and only 13 percent are not interested. They are equally interested when instructors actually have access to this kind of feedback: 58 percent find these technologies extremely or very useful when their institutions provide them, and only 11 percent find them not very or not at all useful.25

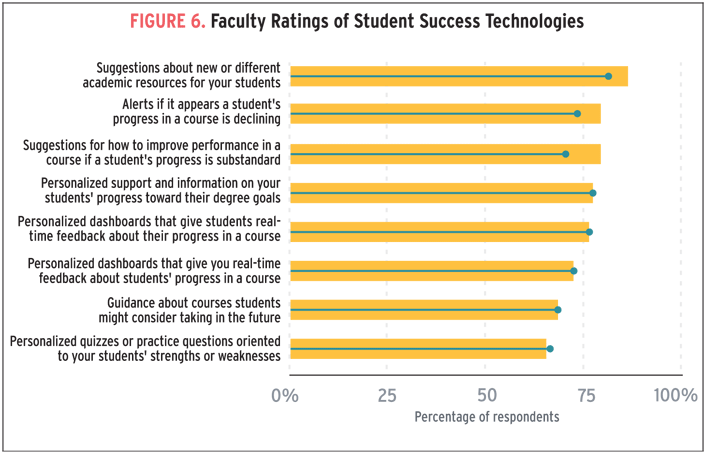

The real challenge in the application of student success technologies to student outcomes is the institution's ability and willingness to embrace change. Faculty are unlikely to resist in large numbers. When asked about an array of technologies that use analytics to improve student success, faculty found them both highly interesting and useful (see figure 6).

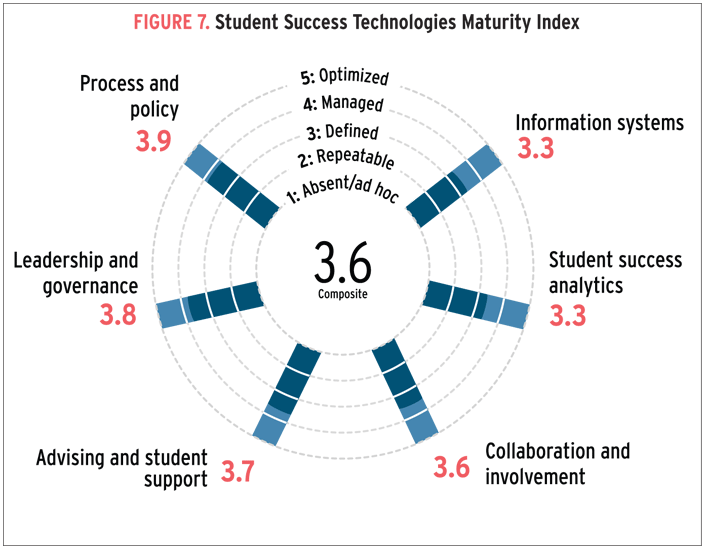

New technologies are only one component of the design that supports improved student outcomes. Effective student success initiatives often entail institutional policy updates, redesigned processes, organizational and role changes, new governance structures, and implementation of tools that require training of and adoption by faculty and staff. Combining expert opinion and research, EDUCAUSE has identified six overall success factors that compose maturity in student success initiatives (see figure 7):

- Process and policy. Policies and requirements for degree attainment, security, and access are clear and adaptable.

- Leadership and governance. Initiatives have leadership support and oversight and adequate funding.

- Advising and student support. Faculty, advisors, and others who work directly with students support the student success goals and use student success technologies.

- Collaboration and involvement. IT, faculty, institutional research, students, staff, student affairs, and other key stakeholders collaborate and participate in decision making.

- Student success analytics. Analytics initiatives and tools are used and useful.

- Information systems. Needed student success technologies are deployed, their data is integrated, and end-users have sufficient training.

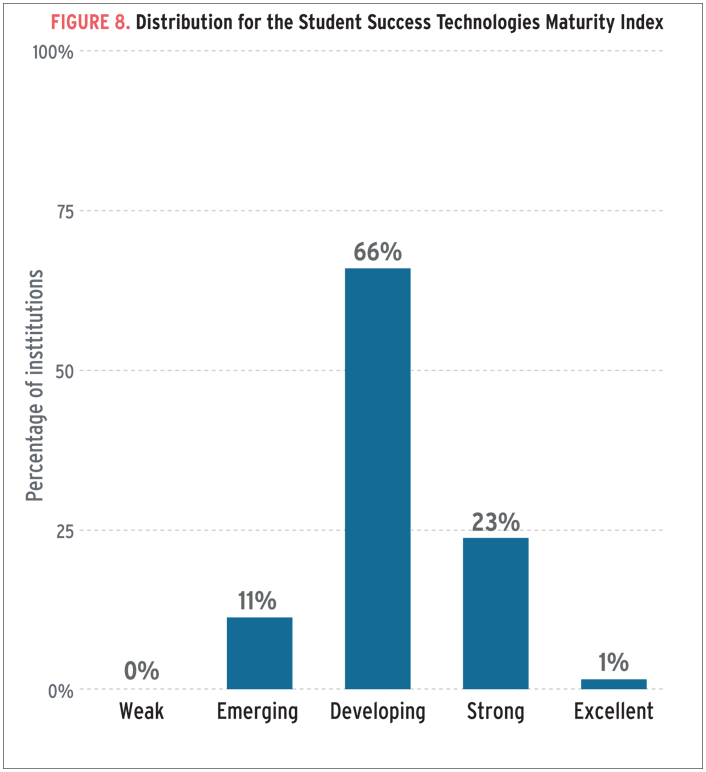

Almost one in four institutions have reasonably strong student success initiatives; the rest are still launching their efforts (see figure 8). Of course, student success efforts are not a "one and done." New technologies will provide new opportunities. The institutions that are leading the way will constantly raise the bar for all. The most successful institutions will be those that adopt continuous improvement practices, so that the cycle of plan-do-check-act is incorporated into ongoing institutional management.

Advice

- Before technology selection, contact other institutions that have deployed similar tools to understand best practices in implementation and outcomes achieved.

- Before launching new student success initiatives, set goals and determine how to measure success.

- Include all stakeholders (e.g., faculty, students, advisors, academic leaders, IT managers) in the selection, implementation, and testing to ensure that the solution will be feasible, affordable, and useful.

- Don't stint on communication and training, which are key components of successful projects.

- Adopt continuous-improvement practices: assess success systematically, use the results to modify, and reassess, always with a goal of improving student outcomes.

- Prepare to play the long game: major change initiatives may take months or even years to bear fruit. Estimate a realistic ROI timeline to help make the decision of whether to stay the course or move on.

- Ensure the institution owns and can modify the algorithms that generate alerts. More important, design the business and support processes that will apply the alerts: determine which interventions will take place across which student service or academic units and how those will be communicated to those units and judged for effectiveness.

- Understand how to integrate data sources and manage private data across a spectrum of student services and academic units, ensure staff and faculty are trained accordingly, and develop a communication strategy so that uses of data are not perceived as intrusive or controlling.

- Complete the EDUCAUSE Student Success Maturity Index to benchmark institutional maturity.

Issue #4: IT Workforce Hiring and Retention

Ensuring adequate staffing capacity and staff retention as budgets shrink or remain flat and as external competition grows

"Speaking on behalf of smaller institutions, I know there is little margin for error if a staff member does not fit within an IT group. It is thus very important for management to do whatever they can to retain good employees. Explore creative compensation ideas with your HR department. Don't be satisfied with the 'we have never done that before here' reasoning."

—William R. Senter, Chief Technology Officer, Texas Lutheran University

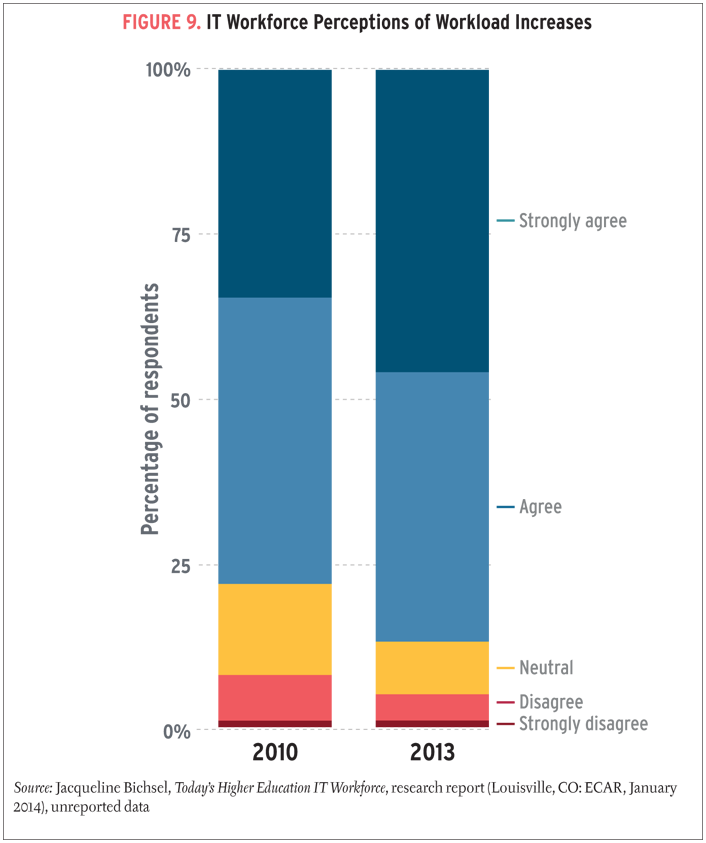

Higher education is now using many of the same technologies as are corporations and private industries around the world, looking for the same technical and management skillsets, and thus competing for the same IT talent. In past years, academic institutions offered staff an appealing set of tangible and intrinsic benefits: more time off, more opportunities to apply technology creatively, the appeal of working in a campus setting with faculty and students, and a highly collaborative professional network—all of which more than offset the generally lower compensation. With the economic situation over the past several years, however, numerous IT organizations have experienced budget reductions, minimal salary increases, declining benefits, and relocations that have separated IT staff from the academic community. Many IT professionals would argue that the one increase they have seen is in workload and expectations, an untenable trend (see figure 9). Today, with cautious rebounds in the economy, particularly in technology jobs, IT talent is a hot commodity. As a result, higher education IT organizations are experiencing increased staff turnover, more aggressive staff recruitment, increasing market salaries they cannot match, and more failed searches. This is not an abstract concern: an estimated 1 in 8 CIOs, 1 in 6 managers, and 1 in 5 IT professionals are likely to leave their current institution.26

Retaining staff becomes a critical priority. In many technology areas, and particularly at small institutions, IT organizations are "one deep" in knowledgeable staff expertise; as a result, those departures could severely disrupt campus services. Many colleges and universities have difficulty offering salaries that are competitive with private industry, but a creative and proactive management team and HR department can improve the odds. Options such as completion bonuses after a long project or even a temporary stipend during a period of critical need can make a difference.

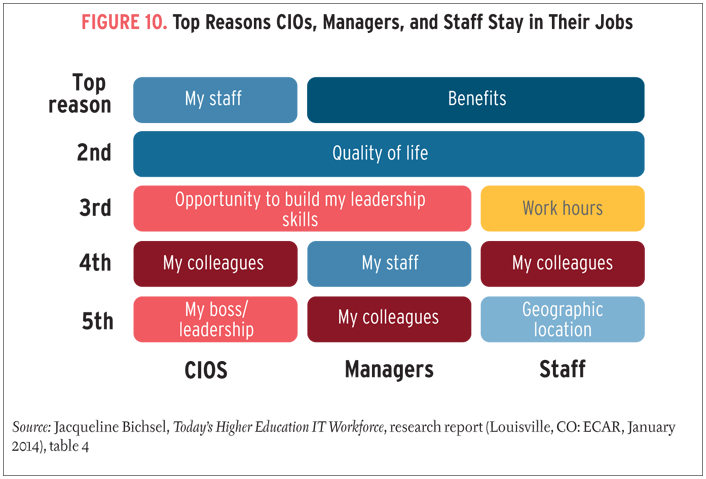

However, compensation is not what primarily attracts or retains most professionals.27 The hard-driving, live-to-work Baby Boomers are giving way to Gen Xers and Millennials who want a better work-family balance. They expect more opportunities for flexible schedules, telecommuting, and updated family and parental leave. Boomers too are hoping to continue past traditional retirement ages in different roles or capacities that flexible organizations can provide. Professional development opportunities and new assignments or projects can also motivate staff to stay. But it is primarily people and quality of life (including the quality supported by good benefits) that retain staff, no matter their age or position (see figure 10). Managers who can develop and foster a collaborative and congenial workplace are the superpower of a stable, high-performing organization. They should be identified, developed, and nurtured.

Workforce diversity is increasingly understood to be both essential and beneficial. Higher education's cultural and organizational structures have evolved within the context of a majority population, a fact that may introduce unconscious and unintentional biases against non-majority students and staff. For IT organizations to be agents of change, IT staff and leaders need to better understand how organizational structures and culture continue to reflect the contexts of a majority population and must then improve those structures and culture to benefit all. And all will benefit. Diverse teams outperform homogenous teams, improving innovation, problem-solving, and productivity.28 Conceptions of diversity should be broad and various: gender, race, age, religion, and sexual orientation are just the beginning.

Advice

- Ensure that staff witness and learn about the benefits of working at the IT organization and the institution. Ensure also that the best employees know their interests are being kept in mind over time.

- Set annual organizational and individual goals, and measure achievement so that staff feel valued and understand the contributions they make. Celebrate successes; have senior executives talk with staff about the role and value of the IT organization; link IT initiatives and services to student experiences, faculty accomplishments, new instructional approaches, and new business processes.

- Proactively manage the organization, roles, and careers. Regularly review staff and positions in the department to prepare for opportunities (e.g., new positions, vacancies) that arise. When vacancies develop, consider how work and roles could be restructured to provide growth opportunities for existing staff. Inform institutional leadership of organizational and staffing changes that are under consideration, so that they will have time to reflect, prepare, and support in advance.

- Develop backup and succession plans, starting with the roles that are most difficult to fill or are most mission-critical. Establish useful and measurable cross-training experiences. Find opportunities to share skills and resources within a state university system or other collaborative.

- Ensure that managers are highly effective, and develop management skills on an ongoing basis. Managing technical people is a very special skill, and few are good at it.

- Investigate options for flexible work arrangements and telecommuting.

- Don't settle. Before hiring, be sure you have (1) the right fit, (2) someone who has a passion for the mission of higher education, and (3) someone who shares the organization's values.

- Build and retain a diverse workforce through effective recruitment, retention, and advancement. Understand and try to prevent the effects of unconscious bias in recruitment, retention, and advancement.

- Include risks related to the IT workforce as part of the institution's enterprise risk analysis. Discuss with the chancellor, president, provost, CFO, and institutional board the human resource challenges the IT organization is experiencing. Leadership will likely be more receptive if the discussion is linked to the achievement of, or the risks of not achieving, institutional goals and strategic objectives.

- IT staff crave professional development and expect it to be an organizational priority. Establish a specific budget and a transparent process for requesting training. However, with tight funding, ensure that all development has a particular end in mind. Include staff professional development as part of each person's goals and each manager's and director's performance review.

Issue #5: Institutional Data Management

Improving the management of institutional data through data standards, integration, protection, and governance

"Institutions should begin with identifying a framework for data management decisions: a data governance model. Ensure the model provides for accountability as well as agility. Data must be managed, but in a way that still allows for rapid development of new applications of the data."

—Brad Judy, Director of Information Security, University of Colorado System

Data is the engine that feeds the higher education mission. It is entrusted to us by faculty, students, alumni, parents, donors, staff, and others to support decisions related to admissions, financial aid, curriculum, research, employees, infrastructure, investments, purchases, and health care. As information technology systems and uses have proliferated over the years, managing the underlying data has become increasingly important.

Much data still exists in silos within our institutions today. This situation is a natural result of the decentralized nature of most colleges and universities and the organic growth of departmental services, often in response to the lack of centralized services and the limitations in the central IT organization's ability to support departmental needs and priorities. It also reflects a failure of most institutions, until very recently, to recognize the value of a strategy in which data is viewed as a strategic enterprise asset, to be leveraged to benefit institutional strategic objectives as well as departmental or operational objectives. Current efforts to identify risk factors to student and researcher success depend on data from disparate sources, internal as well as external to the institution, as do efforts to deliver increasingly personalized services to constituents. With many institutions still grappling with multiple answers to even the most basic data-informed questions—for example, how many students and faculty do we have?—higher education has its work cut out for itself.

Institutions must understand not only what data they possess, but how to care for the data through thoughtful governance and administration. Data governance is a structure empowered by institutional leadership to establish effective standards and practices for data handling and sharing and to arbitrate disputes over access to categories or elements of data. Many institutions begin by clarifying data ownership and by classifying data according to varying levels of confidentiality, compliance requirements, and desired uses. Data administration is a structure (or group) that operationalizes standards for institutional data handling and sharing (including integration) and is responsible for maintaining data integrity; data definitions; authorization, retention, and disposition practices and procedures; and technical architectures. Data management requires ongoing assessment and improvement to maintain compliance with new and evolving regulatory requirements and to retain agility and flexibility.

Institutions that report:

- We have policies that specify rights and privileges regarding access to institutional and individual data: 69%

- Our data are standardized to support comparisons across areas within the institution: 47%

- Our data are standardized to support comparisons across areas within institutions: 37%

—EDUCAUSE Core Data Service 2014

Though often viewed as an "IT issue," data governance is really a larger business issue. Multiple roles and responsibilities are associated with data management. Since all institutional constituents need to understand their roles and responsibilities, education, outreach, and training are critical components of effective data management.

Each institution will organize the work of data management differently, depending on existing organizational assignments and strengths. The 2015 ECAR study of analytics showed that depending on the institution, the CIO, institutional research (IR) director, chief academic officer, president, student success leader, and dedicated chief data or analytics officer are all likely leaders of analytics programs.29 There is no one best practice, other than to designate someone to lead.

Advice

- Design a data architecture and infrastructure that supports both enterprise and departmental needs. Carefully consider data flows and schema, data standards, and definitions to facilitate integration between applications, data security, privacy, retention and disposition policies, and effective governance and oversight.

- Ensure that institutional leadership is involved in data governance and is willing to support and endorse data management policies and procedures, which may become contentious.

- Ensure that data management activities are realistically resourced. This is an added responsibility and should be staffed and funded accordingly. Don't wait for a data breach or analytics initiative failure to invest in data management.

- Those just beginning to address data management should take a methodical approach:

- Investigate: Bring together those with a vested interest in institutional data to discuss the pain points, needs, untapped opportunities, and questions. Get a conversation started about how to best manage institutional data.

- Define: Select a data governance framework for assigning data ownership and accountability and for defining a decision-making process.30

- Inform: Once data roles have been defined, start asking what information people in each role need in order to make informed decisions.

- Prioritize: Focus on the largest pain points and greatest opportunities. This can be a very interesting process, as it will combine the priorities for different data groups. If data retention is the #2 issue for student data, but the #12 issue for HR data, where does that place the priority for data-retention processes overall?

Issue #6: IT Funding Models

Developing IT funding models that sustain core services, support innovation, and facilitate growth

"Savings, if they can be identified (even though not necessarily captured) are still important to highlight. Similarly cost avoidance."

—John C. Meerts, Vice President for Finance and Administration, Wesleyan University

IT funding is the only issue that has made the EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues list every year. Since the challenges in 2016 are not appreciably different from those of 2015, the advice and analysis from last year are worth reviewing.31

The role of technology in higher education has undergone a metamorphosis, but the budget processes at many institutions have largely remained the same. At a time when information technology needs to be agile and flexible, financial resources are often stringently allocated and unavailable to assist institutions in transformational work. In 2014, respondents to the EDUCAUSE Core Data Survey reported that 79 percent of the central IT budget is allocated to running the institution, 13 percent to meeting growth in demand, and only 6 percent to transformation. This 6 percent level of spending on innovation is less than half the cross-industry average of 13 percent, according to Gartner.32 The 2014 Core Data Survey also reported that the central IT organization's median spending as a percentage of institutional expenses was 4 percent. These numbers conflict with the realities of widespread interest in technology investments to improve student success, increase operational efficiency, and advance research. Considering the multidimensional challenges facing colleges and universities, campus communities should feel impelled to critically examine and address the issues that impede technology funding.

Most CIOs state that they long ago trimmed the budgetary fat. EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel members reported:

- "IT organizations survived the recession by cutting and renegotiating contracts and agreements, but now they are running out of things to cut and there are many needs on campus."

- "It is becoming more and more difficult to sustain the giant infrastructure that we built and maintained over the past 10–15 years without a fundamental, sustainable budget. We have a $3 million investment in infrastructure and $50,000/year to replace it. That equipment needs to be updated or refreshed every 5–7 years. If we can't maintain that infrastructure, then eventually none of the other stuff will matter because the infrastructure won't be there."

- "Our institution leaders seem very willing to invest in new things and new services, but they don't want to hear the conversation about the millions of dollars in infrastructure and the fact that we never had a capital budget. Our one-time fund is gone. So leadership views requests for infrastructure maintenance as IT asking for money; but we view it as the money we used to have to maintain the infrastructure."

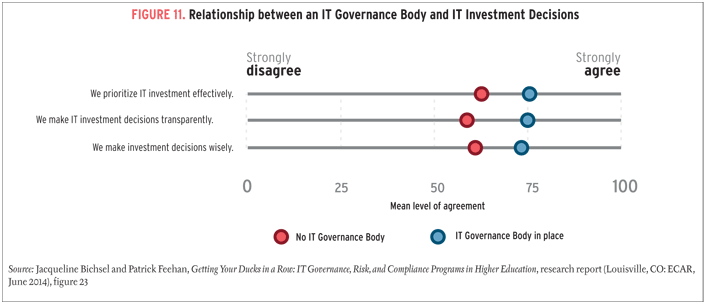

The solution involves improved financial management and reporting and more-effective IT governance (see figure 11). CIOs and CFOs need to develop a shared understanding of and commitment to realistic IT funding. CFOs have the financial knowledge; CIOs understand the magnitude of the investments needed not only to complete a project but also to maintain ongoing operations. A strong partnership can resolve the IT funding challenge. CIOs working with CFOs thus need to make the case for IT investments. Funding for projects that directly affect the mission of the institution (e.g., teaching and learning) is always easier to get than is funding for obscure or hard-to-understand infrastructure. In addition, CFOs hate surprises (who doesn't?). CIOs need to use strategies to minimize surprises: prepare a long-range (five-to-ten years) financial plan for the IT department; present multiyear budgets to the CFO; ask to have carry-forwards to allow underspending in some years and overspending in other years, provided they cancel out within an agreed-upon time frame; and negotiate with the CFO for a fixed incremental amount (or percentage) every year as "new money" and commit to work within those constraints.

For years CIOs have struggled to demonstrate the value of information technology to higher education institutions. Too often "the value of IT" is short-hand for "why we are spending so much money on IT." This framing focuses purely on the cost of information technology and is actually about efficiency rather than value. Value is a function of efficiency and benefits. But when IT organizations are managed as cost centers, and when strategic IT conversations are restricted to expense, information technology will be viewed as necessary but also perhaps as dead weight; an encumbrance rather than an asset.

Advice

- Benchmark IT finances by participating in the EDUCAUSE Core Data Service.

- Ensure that IT projects build models for ongoing operational funding into project deliverables and expectations.

- Establish an institutional IT governance structure that is responsible for allocating funding, not just identifying IT priorities.

- Build the costs of growth and maintenance into funding models for core IT services.

- Tell the story of IT investments to help develop credibility. Help institutional leadership understand and remember the benefits and savings that came from previous investments.

- Work with the CFO to develop a budget model that shows all technology expenditures for the institution, even if they aren't all controlled by the central IT organization and even if they have to be adjusted each year (use forecast modeling). Advocate for IT funding and governance at the institutional level rather than the departmental level to reduce redundant spending and to ensure that the investments benefit the entire institution rather than just those areas that can afford them.

- Align IT services and investments with institutional goals and objectives to show information technology as an investment in the future of the institution rather than as an expense or cost center.

- Adopt ITSM (IT service management) methods for ongoing service management to contain operational costs.

Issue #7: BI and Analytics

Developing effective methods for business intelligence, reporting, and analytics to ensure they are relevant to institutional priorities and decision making and can be easily accessed and used by administrators, faculty, and students

"In order for institutions to continue to expand their analytics capabilities a focused and dedicated effort is needed. No matter the approach, institutions are recognizing that analytics can no longer be an add-on to someone's existing responsibilities."

—Celeste M. Schwartz, Vice President for Information Technology and College Services, Montgomery County Community College

Higher education institutions must become more data driven to capably respond to demands to become more effective and flexible and to meet both mission objectives and regulatory requirements. Business intelligence (BI) and analytics are the keys to unlocking insights that are contained in the numerous institutional data stores. Being able to see trends, ask "what if" questions, discern correlations, move to predictive models, and use those models to take action is becoming a key strategic capability. As IBM CEO Ginni Rometty asserts: "Where code goes, data flows. Cognition will follow."33

IT organizations have developed and managed ever-growing stores of data on students, employees, alumni, and donors, along with a realm of other data from information systems. We have an abundance of data. We also have access to an abundance of technologies and tools. Industry advances in data and analytics are presenting higher education with new opportunities to leverage data and information. IBM Watson Analytics, for example, can take various sets of data from an institution and elsewhere and look for various patterns and information. Adaptive learning tools such as Acrobatiq and Realizeit are cropping up to facilitate and personalize learning. As is all too often the case, however, the real challenge, and the right starting point, is defining the objectives of an analytics initiative and then developing the processes, policies, culture, and people needed to achieve those objectives. As is equally all too often the case, many institutions are starting with the data at hand, purchasing new systems with black-box algorithms, and seeing whether anything useful transpires. Care to wager on the ROI this approach is likely to achieve?

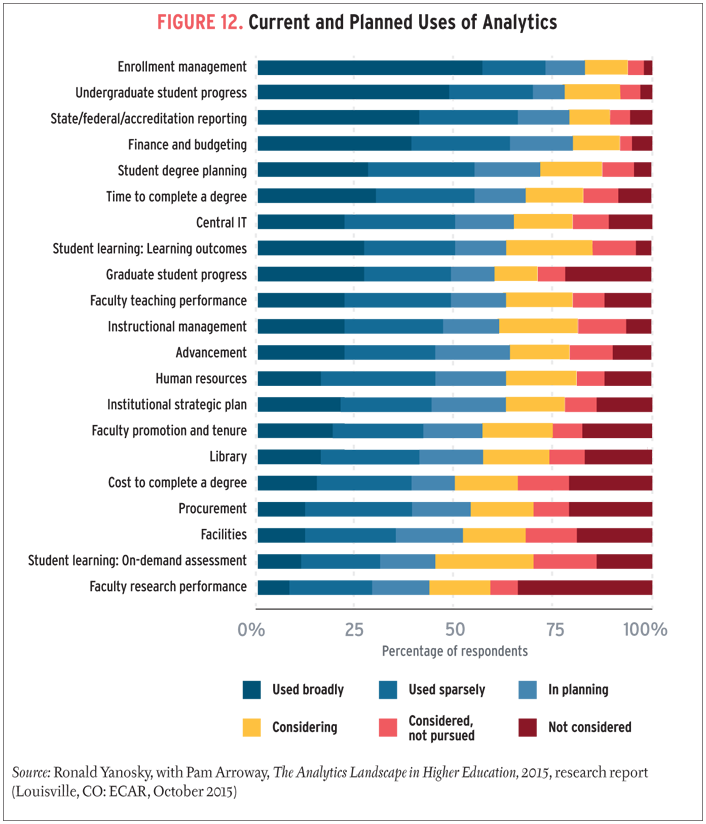

Many colleges and universities have initially focused on applying analytics to the admissions process. Now more attention is being paid to student engagement analytics, individual student learning analytics, and analytics for student success (see figure 12). Both students and faculty are quite interested in the use of student data to achieve these outcomes. Yet whereas institutions are rich in BI reporting dashboard and learning analytics systems, they are poor in predictive analytics for student success.34 As indicated in the NMC Horizon Report: 2015 Higher Education Edition, measuring learning analytics will grow significantly over the next three years.35 We can expect to see growth in higher education analytics for information visualization, in the use of analytics to personalize learning, and in predictive analytics providing actionable insights.

As the use of analytics evolves, institutions will need to advance their analytics maturity. That entails ensuring sufficient funding and resources; fostering a data-informed decision-making culture that results in clear improvements; developing policies for data and analytics security and access; ensuring that data is accurate, standardized, "clean" and useful; and strengthening partnerships between the IR and the IT organizations. EDUCAUSE has an Analytics Maturity Index against which institutions can assess their level of analytics maturity. Overall, higher education has made no measurable progress in analytics maturity in the past two years: fewer than 15 percent of institutional analytics programs might be described as strong or excellent.36

Some existing processes and policies will need to be changed. Data ownership and management currently conform to our highly decentralized leadership models: each office, department, division, or school owns its own data. That's an extremely useful model when the focus is on ensuring that each area has the data it needs to optimize its particular goals and mission and on limiting access to that data. It also works best when data elements are fully contained within individual distributed areas. However, when the focus moves to institutional objectives or when people, funding, and resources are fluid and have multiple "homes," decentralized data ownership can be a serious impediment to achieving such outcomes as student success, resource optimization, and greater transparency.

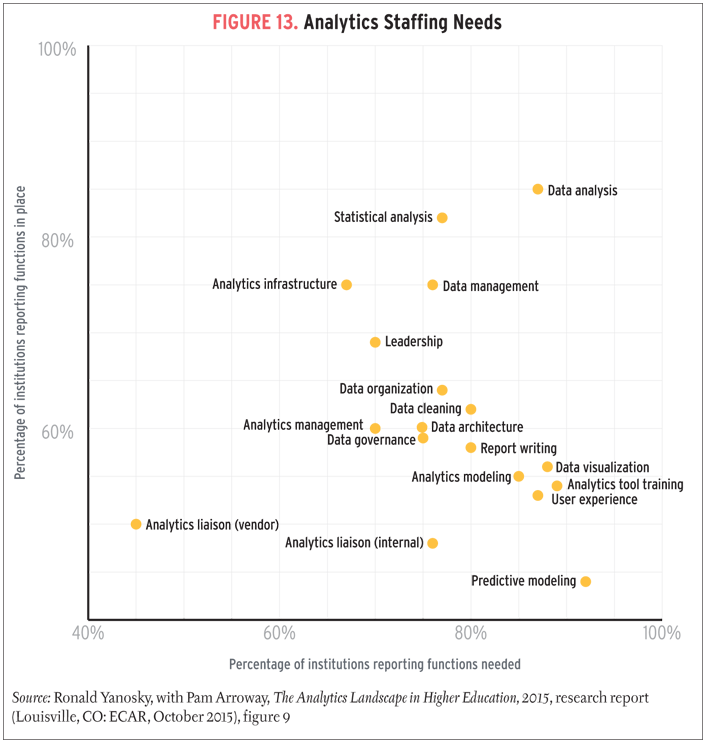

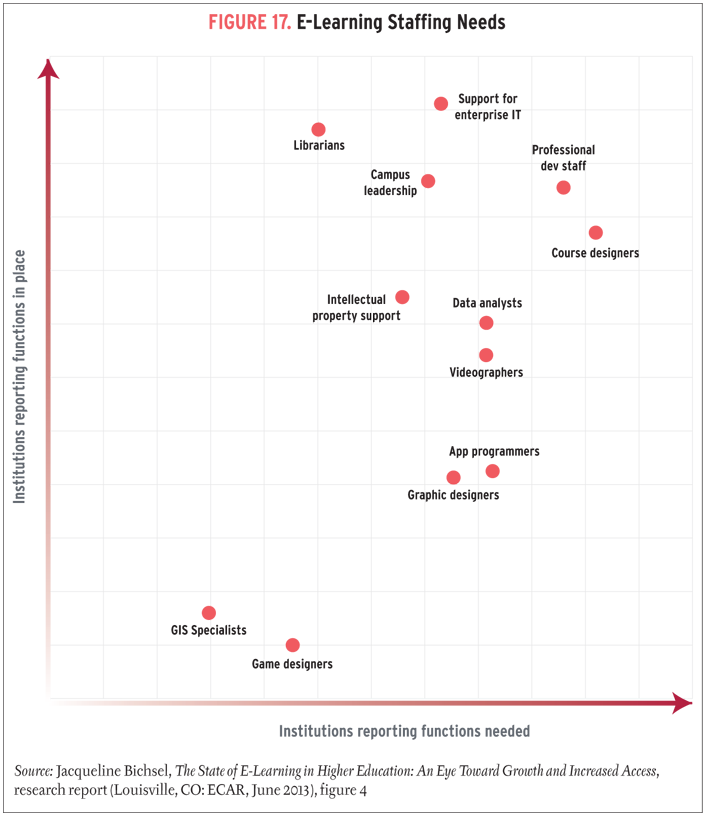

Institutions won't make progress with analytics without the right people. Higher education needs expertise to manage, analyze and model data; to present findings in creative and thoroughly useful ways; and to serve as gateways but not gatekeepers between decision makers and data and findings. Most institutions lack sufficient or any talent in key analytics roles, including analysis and modeling, data management and architecture, data visualization, and user experience (see figure 13).

Advice

- Identify the initial institutional objectives. Look for areas that have urgent, clear needs and want to get engaged. Work with them first. (Student success is often a good starting place.) Always ask what question the initiative needs to answer, how the data will be used, what actions and decisions will result, and what measures should be used to determine if the actions taken have made a difference.

- BI is a collaborative effort. No one has all the keys. A governance structure that consists of an executive steering group of key decision makers with funding authority, aligned with a cross-institution BI working group, can enable progress. At a minimum, the working group should include the IT, IR, and registrar offices.

- Ensure that the initiative has sufficient funding and the right resources. This is not a part-time effort that can be added to existing roles. Consider appointing or hiring an analytics lead whose sole responsibility is to make BI useful on campus. Such a position can provide the glue to keep the various critical data stewards and data users making focused progress and to align the workers with initiative leadership.

- Ensure that the initiative has the right data. Establish, document, and maintain an institutional data dictionary. Institute data management processes.

- After identifying analytics objectives, the data needed, and data governance models, consider business intelligence and data warehouse technology needs. Most institutions will find that initial integrations begin with their ERP data.

- Use an agile, 30-day sprint methodology to provide focus and achieve measurable and timely results.

- Use the EDUCAUSE Analytics Maturity Index to assess the institution's current state of analytics maturity.

- Inventory the institution's current reporting and analytics, and classify items as reports, dashboards, or analytics. Further classify analytics as institutional or learning analytics. Share this taxonomy with others in the institutional community to help enrich their understanding.

- Predictive analytics can provide great insights, but the real test is the actions that are taken based on those insights.

Issue #8: Enterprise Application Integrations

Integrating enterprise applications and services to deliver systems, services, processes, and analytics that are scalable and constituent centered

"For many institutions, service delivery is a competitive differentiator—the ability to deliver 'high-touch, high-quality' services to students, faculty, researchers, and other constituents at scale can have great impact on the level of engagement and, ultimately, the support an institution enjoys from its constituents, as well as on its ability to attract the most talented faculty and most qualified students."

—Gordon Wishon, Chief Information Officer, Arizona State University

Recent changes in the dynamics of the conversation about the value of higher education have caused more institutions to focus on improving constituent services to reduce barriers to student and faculty/researcher success. Today, virtually all services provided by institutions to constituents are delivered through or are supported by enterprise applications—not just those traditionally thought of as part of an ERP solution but also the constellation of ancillary applications that rely on data from the ERP applications or that deliver information in return.

Increasingly, the data contained in these enterprise applications is being used and leveraged through analytics in order to gain insights into what might place a student at risk or to predict certain outcomes and support interventions that might influence those outcomes. In addition, this data may provide insights into ways that service delivery can become more targeted and personalized for each constituent—reducing service "friction," improving constituent satisfaction, and helping to eliminate barriers to success.

Percentage of faculty reporting that their institution

- maintains a highly qualified IT staff: 64%

- has an agile IT infrastructure approach that can respond to changing conditions and new opportunities: 31%

—Brooks, ECAR Study of Faculty and Information Technology, 2015

The wide range of services offered by institutions, coupled with a desire to capture and integrate an equally wide range of service-related data for further analysis, means that most institutions spend a great deal of effort to integrate those applications. The emergence of data architectures and applications that leverage APIs is making the integration challenge somewhat easier. At the same time, the number of applications and data sources is rapidly increasing, along with the amount of data being integrated, frequently resulting in very complex data and applications landscapes and increasingly emphasizing scalability (and supportability). Integration and regression testing becomes more complex and difficult while institutional programming and scheduling demands continue to shrink windows of opportunities to upgrade/update and integrate these applications. In addition, constituents' expectations for the amount of time needed to deploy new systems and services have decreased significantly, and institutions have limited resources to manage and integrate systems and services.

This is a time when both homegrown applications and major ERP and LMS suites are being rethought, reformed, and replaced. Many solutions are moving or have moved outside the institution. It is tempting to believe that the outcome will be a much simpler and smaller IT organization. The reality is not so straightforward. Some management and technical roles are indeed diminishing. But they are being replaced by other, new roles that are essential to having secure, cost-effective, and integrated enterprise applications that meet the institution's business, service, and strategic needs (see figure 14). Most notably, institutions must develop competence in vendor and contract management, information security, enterprise architecture, application integration, and ITSM:

- Vendor and contract management can ensure that the institution is not overpaying, has appropriate terms and conditions, and is purchasing the right components and service levels.

- Information security can audit data and system security and ensure that best practices and policies exist to minimize the likelihood or impact of data breaches.

- Enterprise architecture can ensure that system and data integration is efficient, feasible, and extensible and meets business requirements.

- Enterprise application integration, or middleware, analysts can understand existing and emerging integration best practices and technologies and determine which are most appropriate for the current IT environment and business objectives.

- ITSM can ensure that IT infrastructure and services are well managed to enable fast diagnosis and resolution of problems and to minimize negative repercussions of deployments and changes.

Advice

- Identify the desired outcomes of enterprise application integrations to ensure that they guide the rest of this work.

- Ensure that institutional leaders understand the efficiency and strategic benefits of data and system standardization so that they can and will support the investments and changes needed to achieve these benefits. This work cannot succeed without leadership support.

- Develop an enterprise architecture that can take a holistic perspective on the systems, services, processes, and analytics the institution requires to meet its business needs and strategic priorities. This kind of upfront planning can enable efficiencies and flexibility later. Commit to maintaining it.

- Audit existing enterprise systems and the distributed systems that feed and connect to them to understand current data flows. When new systems and applications are purchased, consideration should be given to whether and how easily they and their data can integrate with existing systems and applications.

- Never lose sight of the importance of the data. Isolated data is of limited use. Vulnerable data is an ugly headline waiting to happen. Ensure that authority and responsibility for data governance, integration, and security are clearly assigned and accountable.

Issue #9: IT Organizational Development

Creating an IT organization structure, staff roles, and staff development strategy that are flexible enough to support innovation and accommodate ongoing changes in higher education, IT service delivery, technology, analytics, and so forth

"Our ultimate challenge is shifting from high operations to high services. But these large systems did not just appear overnight, nor will they change that quickly. We need to have the long game in mind. If we do, our successors will look back favorably on our actions today."

—Dwight Fischer, Assistant Vice President and CIO, Dalhousie University

The IT organization's ability to provide reliable, cost-effective support for daily operations and for innovations in teaching and research is critical to institutional and student success. With the pace of change and the pressures on budgets, an IT organization must be planning for constant and perhaps drastic change in workforce requirements and be preparing to keep those resources aligned with evolving strategies.

The IT organization needs to have a plan to optimize the allocation of human resources in order to maximize the productivity of the individual, the team, the IT organization, and the institution. Three layers should be kept in mind:

- How the IT function is organized and structured at the institution

- How individuals manage their careers and skills

- How the institution supports these activities

Given that IT infrastructures are essentially a very complex system of systems, we need a wide array of skillsets that quickly evolve, and we need a culture of teamwork that supports and encourages the growth of the individual and the team. Organizational development efforts must be part of a long-term and adaptable commitment addressing the people, process, and technology dimensions. Small institutions have very different needs from larger ones. Smaller institutions especially need generalists who have multiple talents and interests, who can thus incorporate several roles into a single job, and who can flex widely as the organizational structure and job duties change.

The organization and structure of the IT function will change over time (see figure 15). It can adapt organically in response to technology changes, personalities, funding changes, day-to-day demands, occasional crises, unclear strategies, and shifting priorities. It can also evolve intentionally to help achieve an institutional vision for using information technology to advance its missions and strategic priorities. The IT organization will change either way, but the outcome will be very different. Using strategy-based organizational development, CIOs can design the organizational structure, competencies and skillsets, and processes and behaviors that the institution needs. Institutional and IT leaders can determine how to most effectively source IT services and functions in order to guide decisions about outsourcing (including to the cloud), centralization versus distributed IT structures, shared services, and even, ideally, which services to stop offering. By doing so, the IT organization can start progressing up the maturity curve and deliver better, more consistent services.

Challenges abound. As technology continues to shift, the clear lines of authority and responsibility may blur, shrink, or even disappear altogether. Much attention is paid to the provision of IT services outside the central IT organization. However, silos can also develop within the IT organization. Without ongoing coordination among the IT leadership team, the IT organization can easily become a series of duplicate "services" centered on the systems and technology (or constituents) that each siloed team supports, rather than a cohesive and continually adapting collection of teams, activities, and roles organized around changing service needs.