What effect do digital devices have on our digital brains? To uncover the influence on learning of using digital tablets for reading, the Coast Guard Leadership Development Center conducted an experiment to ascertain differences in recall and comprehension between tablet and paper readers.

As of 2014, 63 percent of colleges reported using e-textbooks, while 27 percent planned to in the near future.1 But what drives these digital book policies and practices in higher education — technology or research?

Considering the pervasiveness of digital devices, the lack of sufficient guidance for educators to make informed decisions about instruction and learning is disconcerting. Despite the widespread adoption of tablets in schools, ranging from elementary through higher education, research about the effects of tablet use on student learning has obvious gaps. Rapid technological advances and changing features in electronic devices create challenges for those who study the effects of using them; specifically, researchers face limitations in understanding the effects of digital reading on student recall and comprehension. More important, increasing our understanding of the influence of electronic devices on learning will inform educators about the implications of test scores and performance.

Digital Brains: What Research Reveals

"We're spending so much time touching, pushing, linking, scrolling and jumping through text that when we sit down with a novel, your daily habits of jumping, clicking, linking are just ingrained in you."

—Professor Andrew Dillon, University of Texas, who studies reading2

Research yields conflicting results in learning between digital and paper reading in part due to advances in technology and design features.3 While some contradictions reflect variations in research design and methodology, other differences may result from page layouts, such as single- or double-column format. Despite challenges from continuous technological enhancements, studies that investigate differences between digital and paper learners contribute to our understanding of cognitive processes. Collectively, results suggest that students engage in different learning strategies that might short-circuit comprehension when interfacing with digital devices compared to print.

Short Circuits

Researchers have noticed changes in reading behavior as readers adopt new habits while interfacing with digital devices.4 For example, findings by Ziming Liu claimed that digital screen readers engaged in greater use of shortcuts such as browsing for keywords and selectivity.5 Moreover, they were more likely to read a document only once and expend less time with in-depth reading. Such habits raise concern about the implications for academic learning.

According to Naomi Baron, university students sampled in the United States, Germany, and Japan said that if cost were the same, about 90 percent prefer hard copy or print for schoolwork.6 For a long text, 92 percent would choose hard copy. Baron also asserts that digital reading makes it easier for students to become distracted and multitask. Of the American and Japanese subjects sampled by Baron, 92 percent reported they found it easiest to concentrate when reading in hard copy (98 percent in Germany). Of the American students, 26 percent said they were likely to multitask while reading in print, compared with 85 percent reading on-screen.

David Daniel and William Woody urge caution in rushing to e-textbooks and call for further investigation.7 Their study compared college student performance between electronic and paper textbooks. While the results suggested that student scores were similar between the formats, they noted that reading time was significantly higher in the electronic version. In addition, students revealed significantly higher multitasking behaviors with electronic devices in home conditions. These findings uphold recent results involving multitasking habits while using e-textbooks in Baron's survey.8 Likewise, L. D. Rosen et al. found that during a 15-minute study period, students switched tasks, on average, three times while using electronic devices.9 Taken together, these studies point to adaptive habits and cognitive shortcuts while using technology even though learning is the primary objective.

Development and Performance

A 2013 UK survey conducted by the National Literacy Trust with 34,910 students ranging in age from 8 to 16 reported that over 52 percent preferred to read on electronic devices compared to 32 percent who preferred print.10 The data points to possible influences of technology on reading ability: compared to print readers, those who read digital screens are almost twice less likely to be above-average readers. Furthermore, the number of children reading from e-books doubled in the prior two years to 12 percent. According to John Douglas, the National Literacy Trust Director, those who read only on-screen are also three times less likely to enjoy reading. Those who read using technological devices said they really enjoyed reading less (12 percent) compared to those who preferred books (51 percent).

Survey results from the Joan Ganz Cooney Center suggest that parents who read to their three- to six-year-olds with tablets recalled significantly fewer details compared to the same story read using print.11 Together, data from these studies raise concern about overall literacy development in young people.

"Because we literally and physiologically can read in multiple ways, how we read — and what we absorb from our reading — will be influenced by both the content of our reading and the medium we use."12

—Maryanne Wolf

Natalie Phillips conducted fMRI studies to examine brain activity of graduate students while reading Jane Austen (deep reading for literary analysis and reading for pleasure).13 According to Phillips, the research team saw dramatic increases in blood flow to diverse cognitive regions of the brain far beyond those responsible for executive function, regions associated with tasks requiring close attention, suggesting that how people read may be as important as what they read. Phillips concluded, "It's not only the books we read, but also the act of thinking rigorously about them that's of value, exercising the brain in critical ways."14

For example, Ackerman and Goldsmith sought to understand differences in university students' metacognition skills and the effect on the learning process between digital and paper reading modes.15 Compared to digital readers, Ackerman and Goldsmith purported that paper readers manifested greater self-regulation that resulted in better performance. Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick conducted an experiment investigating comprehension with high school students to determine differences between paper and digital forms.16 Students completed an open-book test (hour-long) while they reviewed and navigated either a digital or paper reading. According to the researchers, paper readers showed significantly higher comprehension scores compared to digital readers.

Findings from Johnson's experiment illustrate the challenges in replicating effects.17 Studies by Johnson and Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick compared digital and paper textbook readings followed by open-book assessments. However, Johnson's experiment consisted of college students, whereas Mangen and colleagues studied high school students. Results from Johnson's study did not indicate significant differences in group test scores between digital and textbook readings,18 contrasting with findings by Mangen's team.19 What's more, Johnson's findings were independent of student preferences for either paper or tablet.

Method: Paper or Tablet

Similar to other educational institutions, students at the Coast Guard Leadership Development Center use digital tablets for reading assignments (figure 1). However, we lacked research data to inform us about the effects on our students' learning or performance. Therefore, to uncover the influence on learning of using digital tablets for reading, I conducted an experiment to ascertain differences in recall and comprehension between tablet and paper readers.

Photo: Dave Plouffe, U.S. Coast Guard Leadership Development Center

Figure 1. Senior Enlisted Leadership Course students use tablets for course readings.

I randomly assigned students from existing class groups, enrolled in leadership courses (N = 231), to read either digital (n = 119) or paper (n = 112) versions of a leadership article.20 The experiment consisted of two conditions: paper and tablet readers as the independent variable, and assessment scores from each group as the dependent variable. The randomly assigned groups read either a digital tablet or paper version of the same leadership article, approximately 800 words in single-column format.21 After the reading, students completed an assessment consisting of 10 multiple-choice items for recall accuracy and two short essay questions for comprehension.

Two hypotheses were tested:

- H1: Students who read a paper article will have a statistically significant difference in greater recall accuracy as shown by test scores compared to those who read the same digital article using a tablet.

- H2: Students who read a paper article will have a statistically significant difference in reading comprehension as shown by higher test scores compared to those who read the same digital article using a tablet.

Results

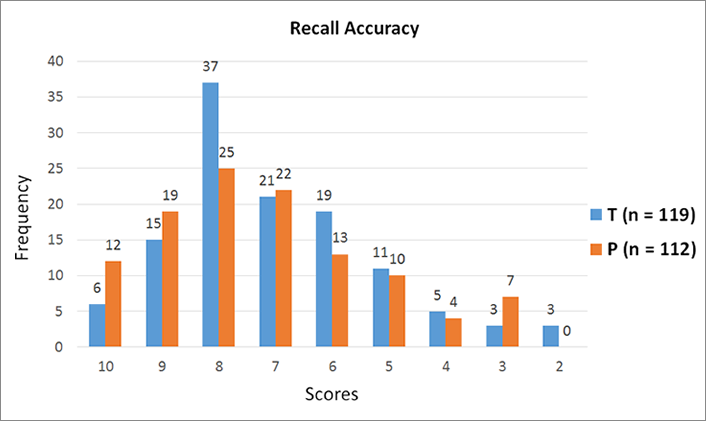

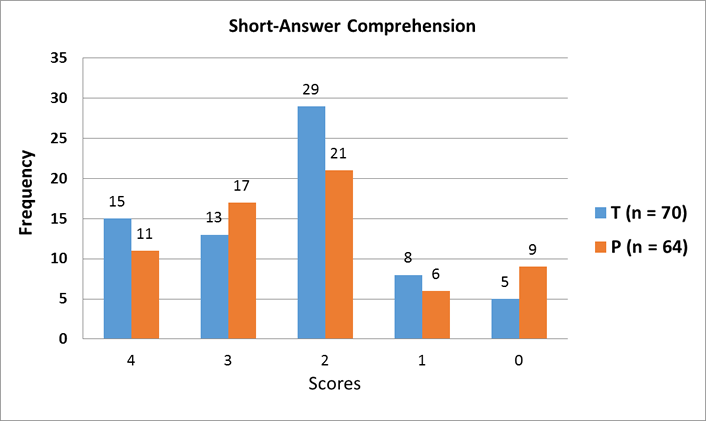

The total sample size comprised 231 students, 119 digital tablet and 112 paper readers. The 10 multiple-choice items were scored 10–0 (high to low), while the two short-answer items were coded for comprehension (4–0, high to low). To determine group differences, t-tests compared scores between paper and tablet readers. Results did not show a statistically significant difference in group means between paper and tablet readers for either the multiple-choice or short-answer items.

Nevertheless, an examination of the range and frequencies of score distributions indicated an emerging pattern: Compared to tablet readers, paper readers had greater frequencies of higher scores for both multiple-choice recall and short answers that measured comprehension (tables 1 and 2; figures 2 and 3). When combining the top two scores for comprehension, paper readers showed a higher percentage. Although there is a greater frequency of score 4 with tablets, this corresponds with a higher frequency and percentage of the mean score, 2. Despite no difference between group means, there may be a difference in individual scores. In particular environments or for specific test purposes such as military selection and ranking, this might indicate a significant factor.

Table 1. Frequencies, multiple-choice, recall (N = 231)

Note: High to low score (10–0).

|

Score |

Frequency Tablet (n = 119) |

Percent Tablet |

Frequency Paper (n = 112) |

Percent Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

10 |

6 |

5% |

12 |

11% |

|

9 |

15 |

13% |

19 |

17% |

|

8 |

37 |

31% |

25 |

22% |

|

7 |

21 |

18% |

22 |

20% |

|

6 |

19 |

16% |

13 |

12% |

|

5 |

11 |

9% |

10 |

9% |

|

4 |

5 |

4% |

4 |

4% |

|

3 |

3 |

3% |

7 |

6% |

|

2 |

3 |

3% |

0 |

0% |

Table 2. Short answers, comprehension (N = 134)

Note: Students for this sample were drawn from the same course. High to low score (4–0).

|

Score |

Frequency Tablet (n = 70) |

Percent Tablet |

Frequency Paper (n = 64) |

Percent Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4 |

15 |

21% |

11 |

17% |

|

3 |

13 |

19% |

17 |

27% |

|

2 |

29 |

41% |

21 |

33% |

|

1 |

8 |

11% |

6 |

9% |

|

0 |

5 |

7% |

9 |

14% |

Figure 2. Multiple-choice items measuring recall accuracy, high to low score (10–0)

Figure 3. Short-answer comprehension scores of students drawn from same course; low to high score (0–4)

Results: Hypotheses

H1: Students who read a paper article will have a statistically significant difference in greater recall accuracy as shown by test scores compared to those who read the same digital article using a tablet was not supported.

H2: Students who read a paper article will have a statistically significant difference in reading comprehension as shown by higher test scores compared to those who read the same digital article using a tablet was not supported.

Although there were no significant differences in group means, there were differences in score frequencies for both recall and comprehension.

Individual score differences can be important for ranking and selection purposes, as in military domains or in granting awards.

To further explore elements that influence test scores, a second experiment replicated the first design and method while also probing for additional factors. Consequently, data collection extended to include (1) student frequency of reading on digital devices for coursework versus paper, and (2) college student status (N = 205). Comparable to the first experiment, no group differences in mean scores appeared between paper (n = 103) and tablet readers (n = 102), but the pattern of greater frequencies of higher scores for paper readers continued. Unexpectedly, frequency of digital device use and college status produced no significant difference.

Discussion and Implications

Johnson's finding offers an interesting comparison with those of this study. Both studies were conducted during the same year and used the same brand of digital tablet (iPad), allowing comparisons between features of the experiments as depicted in table 3.

Table 3. Niccoli vs. Johnson study comparison22

|

Niccoli Study (N = 231) |

Johnson Study (N = 233) |

|---|---|

|

iPad tablet vs. paper |

iPad tablet vs. paper |

|

Unfamiliar reading |

Unfamiliar reading |

|

Two-page article |

E-textbook chapter |

|

Closed-book test |

Open-book test |

A comparative evaluation of the results from both studies indicates two similar patterns:

- No significant difference in group test score means between digital tablet and paper readers

- Higher frequency rates for paper readers of the two highest scores (for recall and comprehension)

Note that both studies display similar patterns in score distributions despite differences in reading length (two pages vs. a chapter). What’s more, the patterns were comparable even though this study was a closed-book assessment compared to Johnson’s open book. However, the shorter reading length for this study and the open-book feature of Johnson’s may present design limitations that influenced results.

Furthermore, both experiments showed no difference in group means, even though the samples differed demographically. Whereas Johnson's study consisted of traditional college students, those for this study were military students with approximately eight years of professional experience.23

Perhaps a longer reading combined with a closed-book assessment will reveal significant differences, especially in comprehension scores. Individual differences of higher scores of paper readers from this study and Johnson’s may reflect factors related to working memory. Studies of reading from computers conducted by Wastlund, Norlander, and Archer highlighted the influence of page layout and scrolling on cognitive demand and individual working memory capacity.24 Likewise, experimental results by Noyes and Garland suggested that reading from screens might interfere with cognitive processing of long-term memory.25

Inconsistencies in cognitive load, reading complexity, study notes, and environment (i.e., classroom, home, and workplace) present contributing factors that influence performance results. Baron asserted that 92 percent of students find it easier to concentrate while reading from paper compared to electronic texts.26 According to Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick’s study, students who used hard-copy texts performed better in comprehension scores compared to those with computers for an open-book assessment.27 Moreover, as reported by Muller and Oppenheimer, students showed higher recall and conceptual scores when studying handwritten notes compared to electronic note taking.28 All together, several design qualities point to variables that contribute to contradictory results.

Final Thoughts and Recommendations

Uncertainties remain about the influence of digital reading for in-depth reading comprehension for adults and raise more unanswered questions about the developmental implications for children.29 The effects of reading from digital devices on children's cognitive developmental skills and literacy abilities are just beginning to emerge. Questions linger regarding the consequences of nonlinear reading on brain processing, especially adaptive shortcuts due to scrolling, scanning, and hyperlinks.30 "There is physicality in reading," explained developmental psychologist and cognitive scientist Maryanne Wolf of Tufts University, "maybe even more than we want to think about as we lurch into digital reading — as we move forward perhaps with too little reflection. I would like to preserve the absolute best of older forms, but know when to use the new."31

Although current findings are conflicting and inclusive, future studies may shed light on the number of variables involved with digitized text and identify features that impede cognitive processing.

If educators understand the effects of digital reading on the development of deep reading and students' grasp of difficult material, they can formulate instructional decisions. Given the current pace of technological change, educators should seize opportunities to further advance our understanding of students' learning while using electronic devices.

Recommendations

- Consider assigning longer readings that create a slight increase in cognitive load for digital readers.

- Include a longer time interval between assigned reading and assessment of students' recall and comprehension.

- Extend these studies of digital vs. paper reading to primary and secondary students to explore their effects on learning and on children's developmental patterns.

- Consider other factors that might affect recall and comprehension among readers using digital and paper texts, such as the types of reading (deep, analytical reading vs. pleasure reading, for example) and the academic discipline of the students studied.

Acknowledgments

The research in this article was presented in the Digital Devices, Digital Brains session at the NERCOMP 2015 Conference.

Sincere appreciation to the volunteer participants of Boat Forces School, Chief Warrant Officers Professional Development School, Officer Candidate School, and Senior Enlisted Leadership Course students at the U. S. Coast Guard Leadership Development Center. Special thanks to the school chiefs for their support in granting time for this study.

Notes

- "Learning technologies being used or considered at colleges, 2013," Almanac of Higher Education, Chronicle of Higher Education, August 18, 2014.

- Michael S. Rosenwald, "Serious reading takes a hit from online scanning and skimming, researchers say," Washington Post, April 6, 2014.

- See, for example, Jim Johnson, "Students perform well regardless of reading print or digital books," ScienceDaily, May 24, 2013; Anne Mangen, Bente R. Walgermo, and Kolbjorn Bronnick, "Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen: Effects on reading comprehension," International Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 58 (2013): 61–68, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.12.002; and Erik Wastlund, Torsten Norlander, and Trevor Archer, "The effect of page layout on mental workload: A dual-task experiment," Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 24, No. 3 (May 2008): 1229–1245, DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2007.05.001.

- Maryanne Wolf, "Our 'Deep Reading' Brain: Its Digital Evolution Poses Questions," Nieman Reports (Summer 2010), Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University.

- Ziming Liu, "Reading behavior in the digital environment: Changes in reading behavior over the past ten years," Journal of Documentation, Vol. 61, No. 6 (2005): 700–712.

- Naomi S. Baron, "How E-Reading Threatens Learning in the Humanities," Chronicle of Higher Education, February 24, 2015.

- David B. Daniel and William Douglas Woody, "E textbooks at what cost? Performance and use of electronic vs. print texts," Computers in Education, Vol. 62 (March 2013): 18-23, DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.016.

- Baron, "How E-Reading Threatens Learning in the Humanities."

- L. D. Rosen, K. Whaling, L. M. Carrier, N. A. Cheever, and J. Rokkum, "The Media and Technology Usage and Attitudes Scale: An empirical investigation," Computers in Human Behavior, Vol. 29, No. 6 (2013): 2501–2511.

- National Literacy Trust, "Children's on-screen reading overtakes reading in print," Media Centre, May 16, 2013 [http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/media/5371].

- Sarah Vaala and Lori Takeuchi, "QuickReport: Parent Co-Reading Survey," Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, September 13, 2012.

- Wolf, "Our 'Deep Reading' Brain."

- Natalie Phillips, interviewed in "MSU lab examines literature's effects on the brain," Current State podcast, WKAR, October 22, 2013.

- Tom Oswald, "Reading the classics: It is more than just for fun," MSU Today, September 14, 2012, Michigan State University.

- Rakefet Ackerman and Morris Goldsmith, "Metacognitive regulation of text learning: On screen versus paper," Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, Vol. 17, No. 1 (March 2011): 18–32, DOI: 10.1037/a0022086.

- Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick, "Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen."

- Johnson, "Students perform well regardless of reading print or digital books."

- Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick, "Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen."

- Johnson, "Students perform well regardless of reading print or digital books."

- Anne M. Niccoli, "The Effects of Reading Mode on Recall and Comprehension," Paper 2, NERA Conference Proceedings 2014 (2015).

- Amaani Lyle, "Chairman Champions Character in Graduation Address," DOD News, June 13, 2013, American Forces Press Service, U.S. Department of Defense.

- Niccoli, "The Effects of Reading Mode on Recall and Comprehension"; and Johnson, "Students perform well regardless of reading print or digital books."

- Ibid.

- Wastlund, Norlander, and Archer, "The effect of page layout on mental workload."

- Jan Noyes and Kate Garland, "Computer- vs. paper-based tasks: Are they equivalent?" Ergonomics, Vol. 51, No. 9 (September 2008): 1352–1375.

- Baron, "How E-Reading Threatens Learning in the Humanities."

- Mangen, Walgermo, and Bronnick, "Reading linear texts on paper versus computer screen."

- Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer (2014, Jun 4). "The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking," Psychological Science, Vol. 25 (June 4, 2014): 1159–1168; Rosenwald, "Serious reading takes a hit from online scanning and skimming"; and Maryanne Wolf and Mirit Barzillai, "The Importance of Deep Reading" [https://www.mbaea.org/media/documents/Educational_Leadership_Article_The__D87FE2BC4E7AD.pdf] Educational Leadership, Vol. 66, No. 6 (March 2009): 32–37.

- Wolf and Barzillai, "The Importance of Deep Reading."

- Rosenwald, "Serious reading takes a hit from online scanning and skimming"; Wolf, "Our 'Deep Reading' Brain."

- Maryanne Wolf, quoted by Ferris Jabr, "The Reading Brain in the Digital Age: The Science of Paper versus Screens," Scientific American, April 11, 2013.

Anne Niccoli, EdD, is an instructional systems designer, Performance Support Department, U.S. Coast Guard Leadership Development Center. She develops curriculum and training programs that cultivate leadership skills for U. S. Coast Guard officer and enlisted personnel. Dr. Niccoli strives to design and instruct resident and blended learning courses to foster critical thinking. In addition to creating the Leadership Development Resources portal, she was a member of the Unit Leadership Development Implementation team awarded the Coast Guard Meritorious Team Commendation. Niccoli holds a doctorate in Education and qualifications in Instructional Systems Design, Master Training Specialist, and Coast Guard Instructor.

© 2015 Anne Niccoli. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.