Key Takeaways

- Applying technology to the process of general academic advisement yields the more flexible, mobile approach called e-advisement, as explained in this case study.

- E-advisement integrates videoconferencing hardware (a webcam) and contemporary software with IM and uses online instructional tools in an advising capacity to improve student success.

- Further research should examine more student narratives in order to gain a better understanding of the student perspective and where they see themselves at the intersection of technology, academic advisement, and accessibility.

By intention and design, the educational process of academic advisement facilitates students’ understanding of the meaning and purpose of higher education and fosters their intellectual and personal development toward academic success and lifelong learning.1 The “intention and design” component has changed as technology quickly became an increasingly important part of academic advisement and student services.2 In this article I discuss the intersection of technology and academic advisement, using literature and data to show that research supports the implementation of e-advisement at public four-year universities.

Delivery of Academic Advisement

The modes of delivery for online academic advisement fall into two broader categories, asynchronous and synchronous advisement. An example of asynchronous advising would be an e-mail exchange between advisor and student.3 This type of advisement provides a delayed response to student inquiries, however, and participants potentially occupy different places at different times.4 Advisors may find it more difficult to establish the most important aspect of student advisement — the interpersonal connection and relationship.5 Synchronous advisement, delivered through videoconferencing technology in real time at the same pace but in a different place, retains the person-to-person feature. Research indicates that this method of advisement has succeeded in higher education institutions.6

Along with videoconferencing technology, the use of instant messaging (IM) between advisor and student has been successfully implemented in many higher education settings.7 Lipschultz and Musser identified the need to share best practices in how to use IM in advising settings as the fields of higher education and technology continue to grow together. Most notably, they explained that the flexibility of IM is both its strength and its weakness. IM increases connectivity and communication, since it allows the student to initiate direct contact with the advisor, as opposed to more traditional methods. In addition, IM allows the advisor to contact the student in the same manner. IM operates between both asynchronous and synchronous categories,8 which can be perceived as a limitation because advisors or students have the ability to intentionally or unintentionally delay their IM responses.

E-advisement integrates videoconferencing hardware (a webcam) and contemporary software with IM and uses online instructional tools in an advising capacity to improve student access, efficiency, and success while maintaining face-to-face communication, the ability to view documents, and live academic goal setting.9 Rey Junco identified three overarching issues as to why higher education institutions need to integrate technologies into effective advising tools:

- Primarily, advisors seek to engage students as the advisement process advances with the hope that they continue to stay engaged and develop their metacognition in terms of academic advisement, even when advisors are not present, as opposed to a student sitting in front of the advisor waiting to be told which courses to select.

- Second, advisement resources are scarce given the current economic climate, and advisors must work with what is available.

- Third, institutional advisors need to meet the students where they are, online.10

Students experience virtual academic advisement almost as if it occurred face-to-face with their advisor. As a result, the student associates a face with the institution and the advisor watches for visual clues from the student.11 Additionally, advisors can share general education charts and graphs, transcripts, and catalog information with students. The student can view these items and respond to the advisor's voice through voice if webcams are used and texts via IM if not. One of the most important notions about e-advisement is that its technological components are not meant to replace the one-on-one student advisor experience, but to supplement that experience in a virtually identical way.12

Case Study

Recently, a public four-year university, a federally designated Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI), piloted online general education and academic probation student workshops using university-provided VC software. Students who attended the academic probation workshops were required to do so per university policy as a form of intrusive advisement. Students who attended the general education workshops did so voluntarily. One of the limitations to the study reported in this article is that the researchers did not disaggregate between General Education Workshop attendees and Academic Probation Workshop attendees in the data. Additionally, student attendance at most of the workshops was consistently lower than expected when compared to “in-person” attendance at comparable public four-year institutions' advisement workshops. Student attendance ranged from 5 to 15 maximum per workshop at this university.

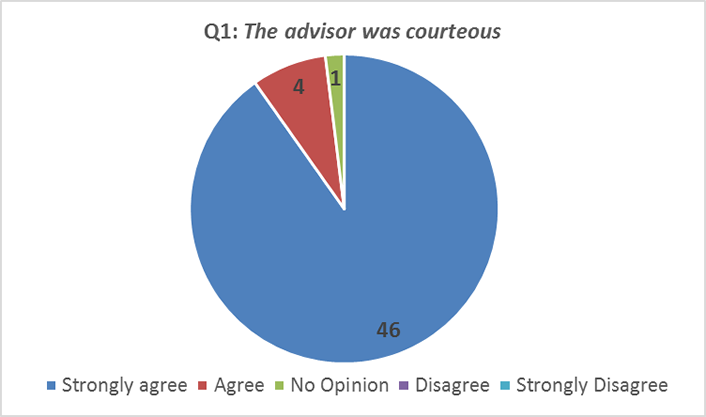

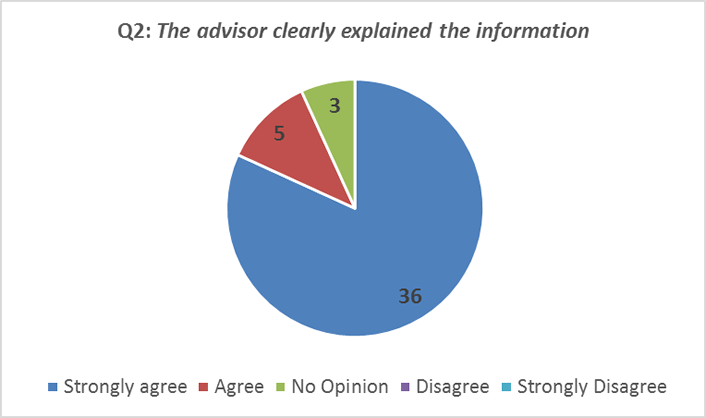

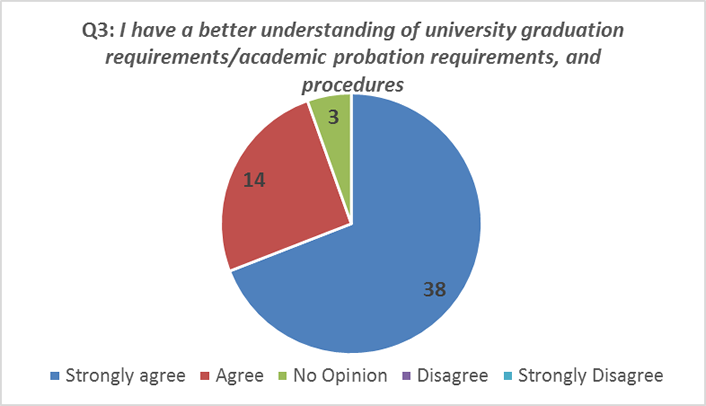

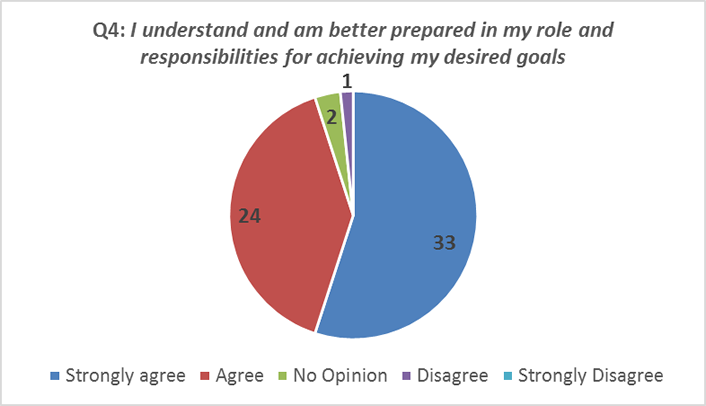

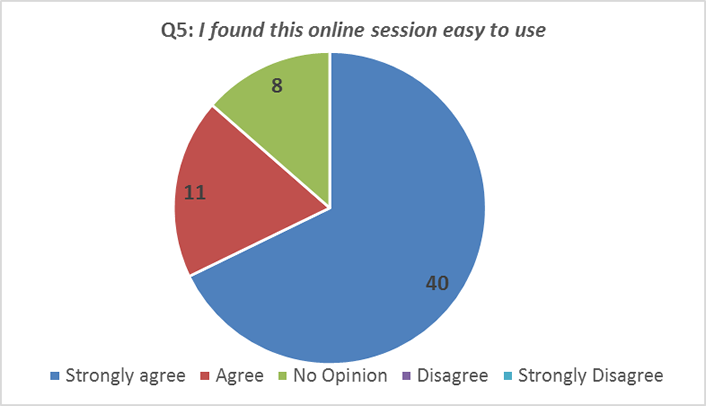

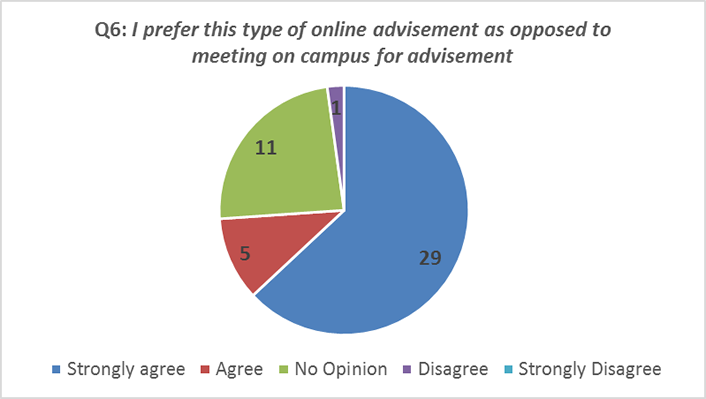

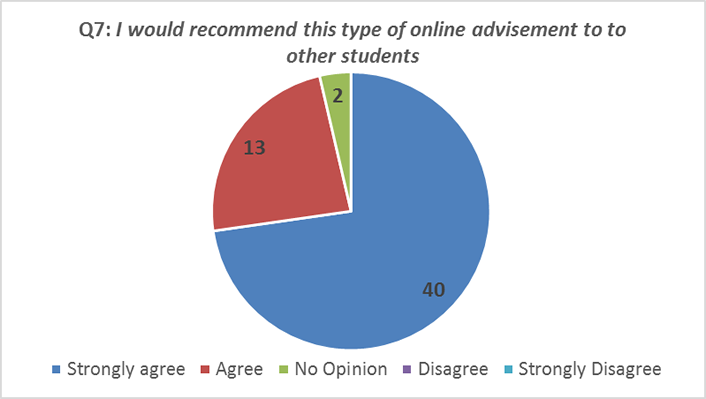

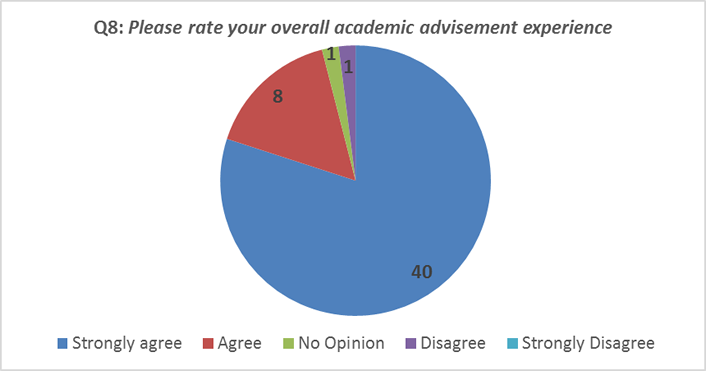

The data for this study was collected on a quarterly basis between fall 2012 and winter 2015. The students were surveyed using contemporary data collection software.13 Not all students who participated in these workshops completed the online survey, which asked them to respond to the following nine statements, with results as shown in the accompanying pie charts:

Q1. The advisor was courteous.

Q2. The advisor clearly explained the information.

Q3. I have a better understanding of university graduation requirements/academic probation requirements, and procedures.

Q4. I understand and am better prepared in my role and responsibility for achieving my desired goals.

Q5. I found this online session easy to use.

Q6. I prefer this type of online advisement as opposed to meeting on campus for advisement.

Q7. I would recommend this type of online advisement to other students.

Q8. Please rate your overall academic advisement experience.

Q9. Do you have any comments or suggestions?

Research shows that positive institutional experiences with institutional agents contribute to students' academic success.14 As the survey data show, the majority of student participants highly approved of this pilot program. In response to questions one through seven, the majority of students strongly agreed or agreed that the workshops were valuable. In response to question eight, an overwhelming majority of students stated they had a positive experience participating in the online workshops. A few students shared their experiences, including the following statements:

“It was very helpful, I recommend everyone to get this type of info.”

“There should be more online advisement workshops at different times.”

Lastly, question nine was intentionally open-ended so that students could share with the advisor their perspective on their own experiences and also recommend any changes. Most of the qualitative feedback was positive, as noted by the following examples of student experiences:

“Highly recommend!”

“No comment, everything was fine, no complaints.”

“The online academic probation workshop helped me to better understand the position I am in and what I need to get out of probation, thank you.”

A small number of students pointed out some technical issues. A few students also suggested sharing more documents prior to commencement of the online workshop session.

Overall, the most recent literature along with more than two years of data and student feedback has shown that, in general, online student engagement works and has been well received by students at the public four-year institution studied. I recommend that more practitioner-researchers further examine the topic and attempt to implement this innovative type of academic advisement. Also, universities should extend their online presence in terms of student services, beginning with offering group or one-on-one online academic advisement sessions.

Concluding Thoughts

The data show that students found integrating technology in their education to be useful. Students should be able to attend an e-advisement session using VC, IM, or a combination of the two, from wherever they are. These sessions should target students who need basic general education academic advisement. Also, the data show that e-advisement works for students on academic probation. Because teaching and learning can be reciprocal, I expect that the skill level of e-advisors, in terms of student services, will increase as more students use e-advisement to meet their needs. This will contribute to the professional development of academic advisors as they incorporate technology into conventional methods of student service.

The structure and details of scheduling an e-advisement appointment depend on the campus environment and academic advisement model implemented. Further research should examine more student narratives in order to gain a better understanding of the student perspective and where they see themselves at the intersection of technology, academic advisement, and accessibility.

Notes

- NACADA statement of core values of academic advising, NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources (2004).

- Zuhrieh Shana and Shubair Abdul Karim Abdullah, "SAAS: Creation of an e-advising tool to augment traditional advising methods," Computer and Information Science, 7, No. 1 (2014): 41.

- Jeff Carter, Utilizing Technology in Academic Advising, NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources (2007).

- Ibid.

- Leora Waldner, Dayna McDaniel, and Murray Widener, "E-Advising Excellence: The New Frontier in Faculty Advising," MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7, No. 4 (2011): 551–561.

- Terri R. Hernandez, Academic Advising in Higher Education: Distance Learners and Levels of Satisfaction Using Web Camera Technology, doctoral dissertation, University of Central Florida (2007).

- Pamela A. Havice, William L. Havice, Tony W. Cawthon, Guy E. Ilagan, "Using Desktop Videoconferencing to Promote Collaboration and Graduate Student Success: A Virtual Advising System," The Mentor: An Academic Advising Journal (December 2, 2009).

- Wes Lipschultz and Terry Musser, "Instant Messaging: Powerful Flexibility and Presence," NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources (2007).

- Waldner et al., "E-Advising Excellence"; and Shana and Abdullah, "SAAS."

- Rey Junco, "Using Emerging Technologies to Engage Students and Enhance Their Success," Academic Advising Today, 33, No. 3 (September 1, 2010).

- Hernandez, Academic Advising in Higher Education.

- Carter, "Utilizing Technology in Academic Advising"; and Shana and Abdullah, "SAAS."

- The student survey was collaboratively designed by the author and the director of online instruction at the four-year university prior to fall 2012.

- Vincent Tinto, Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1987); Ricardo Stanton-Salazar, "A Social Capital Framework for Understanding the Socialization of Racial Minority Children and Youths," Harvard Educational Review, 67, No. 1 (1997): 1–41; and Anne Marie Nuñez, "Latino Students' Transitions to College: A Social and Intercultural Capital Perspective," Harvard Educational Review, 79, No. 1 (2009): 22–48.

Jimmy Solis is an EdD student in the Department of Education at the University of Southern California. His research interests include underrepresented student access and achievement, technology in higher education, multicultural education, and administrative leadership.

© 2015 Jimmy Solis. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.