Key Takeaways

- Although inevitable — and often beneficial — change is hard for everyone involved because it forces us think, feel, and act in new ways.

- IT personnel often struggle with change more than people working in other areas; in particular, they perceive a lack of personal influence on their larger group or the overall enterprise.

- Understanding how change affects people and working with key factors such as motivation and trust can help leaders manage inevitable change in a way that empowers and improves IT organizations and the people who work within them.

- Penn State University's IT Transformation Project offered fertile ground for a study of how IT people experience change and how to help them best navigate change in their work tasks and roles, as well as in their overall environment.

Change has become a trademark characteristic of today's IT context. To meet the demands and fluctuations of an unpredictable environment, the leader's role must increasingly focus on instigating the change required to meet the needs of a dynamic world.1 For more than a decade, IT management trends and concerns have included the need for all IT organizations to align with business needs, have more agility, and manage relationships more productively.2

Although changing with the times usually benefits people, it can be difficult for those involved because change forces us to think, feel, and act differently, which requires personal effort. Change makes heavy demands on people in terms of workload, uncertainty, competing priorities, and meeting client and customer needs; it also taxes us mentally, emotionally, and behaviorally. Such pressures must be acknowledged, appreciated, and addressed.

In my research on change and motivation among IT personnel, three important findings emerged related to how IT personnel deal with organizational change, identify with their work, and get work done.3

- IT personnel tend to struggle with organizational change.

- IT personnel are generally motivated workers, and yet they do not feel they have much impact on the group or organization for which they work.

- The level of trust people have in their supervisors is a critical component in the relationship of employees to the organization as a whole.

In this article, I highlight how change affects people and how working with the related factors of motivation and trust can help those going through or leading the process of change. I also offer practical ways to think about and manage change.

How Do IT Personnel Respond To Change?

Finding 1: IT personnel in higher education struggle with change more than personnel in other occupations.

Responses to Change

An informal comparison of my research to studies of other groups showed that IT personnel in higher education tend to be more resistant to change than personnel in almost all other occupations and sectors.4 This might surprise some people; after all, IT is a field in which change is constant. However, I suspect that the pace of change in IT pushes IT personnel to work closer to a threshold for change tolerance than people in most other fields. Also, the type of change my research focuses on is not technological change per se, but rather organizational and interpersonal changes that affect not only how we do our work but also how we see ourselves and our lives. As Tech Data CIO John Tonnison noted, "when you change something, you put at risk the confidence an individual has in their ability to get things done."5 Examples of this type of change include improving organizational culture, implementing or revising organizational processes, adopting new technologies, reorganizations and establishing new reporting lines. Elspet Garvey, business process manager at the University of Auckland, noted that the way people perceive this type of change depends on a person's organizational role: "Executives see [change] as something happening to the enterprise, and employees think of it as something happening to them."6

Everyone has a different level of comfort with uncertainty, so it seems reasonable that everyone has a different response to changes imposed on them. The range of change tolerance is broad, but we can measure (and therefore anticipate more accurately) the level of difficulty individuals might have with a given change. More importantly, we can do things to help individuals become more comfortable with the change process. Also, it is important to recognize the strong emotional component of change and to avoid both diminishing levels of trust in the organization and emotional withdrawal from the organization.7

The "Resistance" Problem

Discussing "resistance to change" in itself can unnecessarily polarize people because the mere mention of the term "resistance" implies clearly drawn battle lines, which might not exist. In fact, research remains divided on the issue.8 Still, individual resistance is part of the change puzzle.

With a balanced approach, leaders can focus on removing barriers to change, which are neither beneficial nor productive. Think of resistance here as a symptom rather than a cause of problems. The cause might be individual, of course, but other factors could also interfere that we can improve (reward systems, communication channels, conflicts that can be resolved or averted, etc.). Once underlying sources of concern are addressed, people might become open to embracing the change initiative in question.9

Managing Change vs. Change Management

As a case in point, in IT at Penn State University we are undertaking the IT Transformation Project (ITX), a large change initiative focused on taking a more IT service orientation in our systems and offerings. Among the project goals are to

- improve efficiency and effectiveness;

- create a more unified experience for our customers and clients; and

- free up local IT units to provide higher levels of white glove service, more support for research, and increased innovation.

As part of ITX, we've devised and launched a phased approach for transitioning to 11 common service-management processes in the ITIL framework.10

The purpose of change management is to keep processes and procedures in place so that IT can provide continually improved service. In contrast, managing change is an intra- and interpersonal process focused on how each individual copes with or adapts to the changes occurring. As such, managing change relates to employee attitudes and habits, because change requires people to alter how they work. It can also cause people to think about themselves in fundamentally different ways, to call upon additional cognitive resources, and/or to change their emotional state or stress levels. To succeed, this more personal aspect of change requires personal effort and, sometimes, personal sacrifice.

Because change brings uncertainty, projects such as ITX can represent risks to individuals. These risks can be even more compelling when the change requires a fundamental shift in how members of the organization think about themselves and the organization as a whole11; for example, when an organization changes from a technology provider to a service provider.12 This uncertainty is highlighted by the fact that more than half of all change initiatives fail.13

Change is hard for everyone, but building resilience at both the individual and organizational or group level can make it easier.

How Individuals Can Build Resilience

To build resilience in individuals requires understanding the differences between adapting to change and coping with change, and to act on that understanding.

Research shows that when confronted with change, people generally ask themselves two questions — and quickly reach answers to both14:

- Is this change an opportunity or a threat?

- How much control do I have in this situation?

If the change represents an opportunity, individuals will likely get more involved in the situation and be more agreeable toward it. If looks like a threat, they will likely engage in protective behaviors. For question two, when people have a high level of control, they will likely work to either maximize the opportunity's advantage or minimize the threat's effect. If they feel they have little control, they will tend to be less involved, but remain agreeable toward the opportunity; in the case of a threat, they will begin to engage in self-protective behaviors to ward off the negative effects. Table 1 summarizes these user adaptations.

Table 1. Coping model of user adaptation15

|

|

High Control |

Low Control |

|---|---|---|

|

Opportunity |

Benefits maximizing |

Benefits satisficing |

|

Threat |

Disturbance handling |

Self-preservation |

An individual's answers to the two questions typically results in one of four responses16:

- Benefits maximizing occurs in an opportunity/high-control situation. In these cases, most adaptation efforts will be problem-focused — concentrating efforts and resources on those aspects that will bring the greatest benefit.

- Benefits satisficing occurs when the circumstances of a change are seen as an opportunity, but the respondent has little control. In this scenario, both problem- and emotion-focused adaptation efforts are likely to be minimal, because the person has no real ability to intervene and no need to self-soothe.

- Disturbance handling occurs when changes pose a threat and the person has a high level of control; in this case, a mixture of problem- and emotion-focused strategies is likely to emerge. The problem-focused tactics will be used to manage the situation in the best possible way, while the emotion-focused tactics will help the person return to a calmer emotional state.

- Self-preservation occurs when there is a threat and the person has a low level of control; here, efforts will focus on restoring emotional stability by reducing anxiety or discomfort emanating from the event (such as through self-soothing, avoidance, and/or self-protective behaviors).

The more problem-focused the response, the healthier it is likely to be. Responses become less healthy when they become more emotion-focused. Knowing this allows individuals to self-monitor as well as provide support to others as needed throughout the process of change; being more adaptable also improves performance.17

A great example of this occurred during our ITX change process when the newly formed project team was still coming together and needed a process manager. An individual was chosen, but this project was already six weeks behind schedule and no effort was made to rebalance the person's existing workload or address the considerable backlog of project work. Mixed expectations also existed regarding how to clear the project backlog.

In such a situation, many people might initially curl up and hide from the world rather than face the overwhelming amount of work expected of them. Instead, this individual took it upon himself to learn the program's structure and engaged people in conversations to gain a proper perspective regarding what was actually expected of him. He then made arrangements with his supervisor to adjust his workload so that he could focus on the priorities of the change initiative, considerable though they were. So, instead of succumbing to the crushing amount of work he inherited, this individual took time to breathe and to make arrangements for his day-to-day work so that no balls would be dropped. He then ran large data collection efforts and workshops that improved data accuracy and managed the expectations of program stakeholders, both of which contributed to the program's success. So, in this case, individual initiative and poise, combined with a little organizational flexibility, were the ingredients needed to move through a six-week backlog. By focusing on the problem rather than the burden, he was able to bring about an important turnaround; this work became one of the strengths of the program.18

As this example demonstrates, dispositional, interpersonal, organizational, and environmental factors can contribute to — or soften — resistance to change.19 It is thus important to understand as much of a given scenario as possible to enable an effective response to factors that can be addressed, particularly in cases where other factors (such as conflict) might increase resistance among all involved.

Additional ways to encourage adaptability include defining job responsibilities by role, competency, and niche — rather than by technology or task — thereby allowing individuals the ability to explore, seek development opportunities, and think of themselves in different ways. Offering and visibly delivering training and growth opportunities encourages people to invest in their situation; it also increases loyalty to the organization. Finally, understand that many of those you are trying to develop might be relatively new to their positions and/or may only be in that position for a few years before seeking a new opportunity. Developing those employees' skills and emphasizing their contributions to the group engender trust and encourage reciprocity.20

When people feel their leaders and managers have their best interests at heart and see the promise that change offers, they are likelier to view change as an opportunity rather than a threat. They are also more likely to feel that they have some control of their situation and act accordingly.

Organizations and Resilience

Individuals and organizations alike have simultaneous and sometimes conflicting needs for stability and change. One effective way to achieve a balance is to engage in organizational rituals that allow organizational members to momentarily suspend their focus on how things are and consider how things could be.

We've found that getting people in a room is bar none the best way to get them to deal with change.

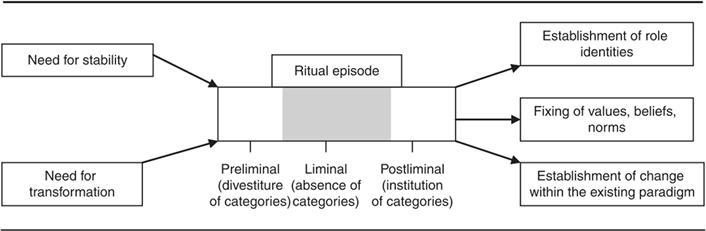

The frequency and intensity of rituals can vary, but consistency in holding them is a good way to keep a team or organization adaptable and nimble. This is because rituals help organizations balance — or rebalance — the needs for stability and change, manage anxiety, provide meaning and direction, build solidarity and commitment, and prescribe and reinforce significant events.22 Gazi Islam and Michael Zyphur23 analyzed the literature on the effects of organizational rituals and ceremonies on organizations and suggest a powerful model for the organizational ritual process that captures these characteristics (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual model of the organizational ritual process24

Healthy organizational rituals give members tools to manage change and foster an atmosphere in which members understand that change is a part of organizational life. These rituals also help build strong relationships among organizational members at all levels. Having rituals in place before undergoing a change initiative helps change go more smoothly. The likelihood of successful change initiatives increases when organizations share information as freely and quickly as possible, encourage participation in the change process, and facilitate relationships of trust among members.25

Two elements are key for successful rituals: they occur predictably, and they have symbolic meaning in terms of helping (re)balance the simultaneous needs for stability and change. In addition, a number of other characteristics also contribute to success, including that the rituals involve activity; are organized, have elements of predictability and variety; are communally focused; carry expectations for behavior going forward, and are interpreted by the ritual's consumers rather than its producers. The more of these additional characteristics that are present, the more likely that a ritual will be an effective instrument of change.26

Rituals are powerful community building tools. A recent article by Henry Mintzberg highlights the need for leaders to create a community that can mobilize and take action in meaningful ways. As Mintzberg put it, "We tend to make a great fuss about leadership these days, but communityship is more important. The great leaders create, enhance, and support a sense of community in their organizations, and that requires hands-on management. Hence managers have [to] get beyond their individual leadership, to recognize the collective nature of effective enterprise."27

For example, at Penn State we recently created a new sub-unit of our central IT organization focused specifically on making IT more service oriented. This involved approximately 120 individuals overall and affected many more than that after new reporting lines were drawn, groups were formed, and responsibilities were created. In order to make this reorganization as successful as possible, a series of meetings were organized, and a strong percentage of the new organization was engaged in the process over several months. One common objective of the meetings was to continually strike a balance between meaning making and enjoyment. This allowed us to get outside of our own heads and make the process as enjoyable as possible, but still tackle the weightier matters of the transition. Because the reorganization was structured as a work in progress with intentional goals and guidelines that organizational members were involved in creating, the transition was relatively smooth. Successful change requires factors beyond simply implementing the right types of events — actions like encouraging involvement and sharing information early give organizational members time to think about and accommodate changes. That is, it gives them time to respond, rather than react.

Of course, rituals need not be complex to be effective; indeed, simplicity makes ongoing rituals easier. For example, one IT group at Penn State is heavily involved in the ITX initiative and therefore felt more of the pain of change. This group started a simple practice of having daily stand-ups, in which everyone shares what they are working on and what their "blockers" are. This simple routine has become an important component to building camaraderie: it helps all members become accustomed to the idea of reporting out, talking about successes, offering support when others feel overwhelmed, and asking questions when challenges are outside their expertise. It also helps get people out of their chairs and puts faces and names together, both inside and outside of the group. What's more, the daily stand-ups have given this IT group a more unified face for its customers and helped improve those customer relationships. Although not sophisticated, this activity is consistently practiced, and, as a result, the unit manager said the group has become "socialized,"28 which is making a difference in terms of improved teamwork, pulling in the same direction, and more graceful handoffs of requests.

Some rituals should aim to create ongoing meaning, clarity, and understanding, regardless of whether change is imminent. Others should be meaningful in terms of creating enjoyment. One administrator recently lamented to me, "We don't celebrate anything in (our) IT." Different IT units approach celebration in different ways, but large or small, public or private, deliberate and regular attempts to recognize accomplishments and create meaning and enjoyment benefit employees, regardless of the organization or their position in it.

What Motivates People Who Work in Higher Ed IT?

Finding 2: People who work in IT in higher education do not feel that they have an impact on departmental outcomes or decisions.

Lacking Impact

Among the higher education IT personnel who participated in this research, most find meaning in what they do, feel they have autonomy, and believe they are good at what they do. However, 68.5 percent of respondents felt they had little or no impact on their department.

Intrinsic motivation — also known as psychological empowerment — relates to high levels of performance on the job resulting from the enjoyment found in doing it.29 Such empowerment leads to increased effectiveness and innovation. When all team members are (or feel) empowered, there is a sense of vision that team members strive toward with energy and dynamism. This increase in momentum affects creativity and performance, which in turn further feeds into the energy that comes from feeling empowered.30 However, as leaders, it is important to remember that empowerment is something fostered and facilitated, not given.31 In other words, we must learn to create an environment in which individuals can develop a sense of empowerment. This requires consideration, planning, and (sometimes) patience.

When you break psychological empowerment down into its component parts, higher ed IT employees rank fairly high on three out of the four factors — a sense of meaning, autonomy, and a feeling of competency. However, most do not believe they have much impact or influence on their group or organization. This is an interesting finding; research shows that a follower's sense of impact is related to increased delegation of responsibility by leaders after three months' time.32

Individuals and the Sense of Impact

To improve a person's sense of impact, it's important to understand the principles associated with exerting influence.

Some researchers argue that every organization primarily exhibits one of four mindsets in terms of how they think about the work they do, how they do it, and why they do it in that way. In an influential book that not only captures this idea but also gives guidance on how to work within each mindset, Lee Bolman and Terrence Deal provide a good representation of the different ways organizations function.33 These default modes of thinking, or frames, that organizations use (usually without even being aware of it) play an important role in how individuals within each organization interact and how all individuals, including effective leaders, are expected to act — and why.

- Structural frame: In some units, efficiency and exactness are the core drivers and measures of success; the more solved tickets or widgets created without error, the better.

- Human resources frame: Units that operate in this frame focus on ensuring that all individuals are well supported; development is a high priority.

- Political frame: Here, different actors work to build coalitions and exercise influence in favor of objectives. As one leader put it, "To make a system self-sustaining, you need buy in."34

- Symbolic frame: In a unit where this is dominant, inspiration and serving a higher purpose are paramount.

Table 2 briefly outlines leadership roles and their effectiveness for each of these frames.

Table 2. Effectiveness and the four leadership frames35

|

|

Effective Leadership |

Ineffective Leadership |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Leader's Role |

Leadership Process |

Leader's Role |

Leadership Process |

|

Structural |

Analyst, architect |

Analysis, design |

Petty tyrant |

Management by detail and fiat |

|

Human Resource |

Catalyst, servant |

Support, empowerment |

Weakling, pushover |

Abdication |

|

Political |

Advocate, negotiator |

Advocacy, coalition building |

Con artist, thug |

Manipulation, fraud |

|

Symbolic |

Prophet, poet |

Inspiration, framing experience |

Fanatic, fool |

Mirage, smoke and mirrors |

Every organization will have elements of all four frames, but will typically privilege one above the others. Furthermore, subunits within an organization can manifest preferences for different frames, particularly if the organization is large or subunits are loosely coupled. Thus, in IT units spread across a college or university, different groups will develop preferences for different frames and operate in those frames — often without thinking about it. The ability to effectively move between frames based on circumstance and group lets individuals build unity and a common vision with others and therefore increases their impact.

I have observed that, of the four frames, the political frame is perhaps the most distasteful to many in IT. However, those individuals who venture into this realm find it an effective way of getting things done — and a way that many of their peers are unwilling to attempt. As such, the political frame becomes a disproportionately useful way of gaining influence and having impact in IT. deliver

Many ways exist to analyze a situation from a political perspective, including mapping stakeholders; using strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analyses; and using force-field analyses. However, these methods look only at a situation. Two crucial characteristics of pretty much any influence strategy include having a relationship with the person or group you are trying to influence36 and understanding that influence is an iterative phenomenon.37

An example here comes from the ITX project, where a member of our transition team recognized that progress comes in a variety of packages.38 He noted how difficult he found it to continually make small improvements to a deliverable and provide those improvements iteratively as opposed to perfecting the deliverable and providing the final version all at once. Once he got the process, however, he felt the momentum really kick in. As this example shows, when people struggle with a particular effort, they engage with it — which is far better than apathy. That said, first attempts might succeed. In fact, first attempts at persuasion succeed more frequently than many of us think.39 If not, keep in touch and try a different approach next time (and maybe the time after that). This could be the ticket to gaining support for an initiative or program.

Understanding and working in the political frame by building relationships is critical to both present and future effectiveness and success. Although common knowledge, this component in practice is frequently overlooked or neglected due to fear, inertia, and so on. Regularly and deliberately acting to develop relationships builds networks that provide sources of support, information, inspiration, guidance, growth, and opportunities. This is vital in an era when the boundaries between IT and the rest of the enterprise must decrease to bring about change and maintain a competitive advantage.40

Organizations and the Experience of Impact

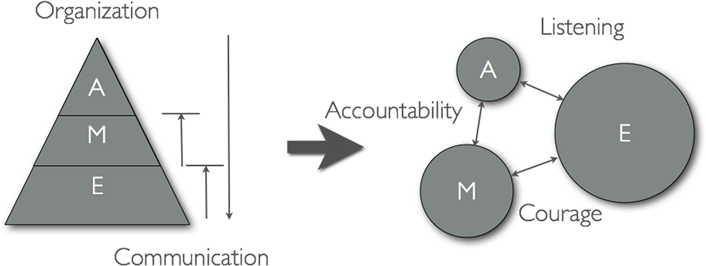

It is important to revisit communication paths and processes. In addition to understanding and responding to the mode of thinking that a group or organization most values — and speaking to that way of thinking — it is wise to examine the organization's flow of communication and information pathways, which rarely follow the organizational structure. In my research, individuals at different levels of the organization clearly had different communications needs. For example, higher-level administrators needed more information from employees (in particular, more accurate information about their needs); thus, that relationship would be best improved by developing better practices and methods of listening. Managers, who typically have considerable influence on administrators and employees, must have more accountability for the fidelity of the information that passes through them. Thus, communication from them needs less filtering. Finally, to effect change, employees might need to muster more courage and find the avenues through which they can voice their concerns or difficulties without fearing retaliation. Figure 2 outlines these suggested changes in organizational communication patterns.

Figure 2. Suggested changes to communication patterns (A = administrators, M= managers, E = employees)

"We Started Listening"

After collecting and analyzing a second round of data, I discussed the findings with Steve Fleagle, CIO at The University of Iowa, noting the impressive improvement in its motivation and trust level scores. When I asked him what they did to inspire change in these areas, he said: "We started listening."41

Fleagle told me about some of the efforts he and his leadership team had undertaken, including holding office hours so that staff could talk with supervisors and leaders about concerns and ideas. In part due to these efforts, the team also learned that staff members found several processes (including a project proposal system) both confusing and intimidating. So, the leadership team made changes.

By demystifying processes and freeing up managers' and administrators' time, the team could give members of the organization an increased sense of impact and greater levels of trust. Small changes can sometimes have significant effects.

How Can Organizations Build Trust and Relationships?

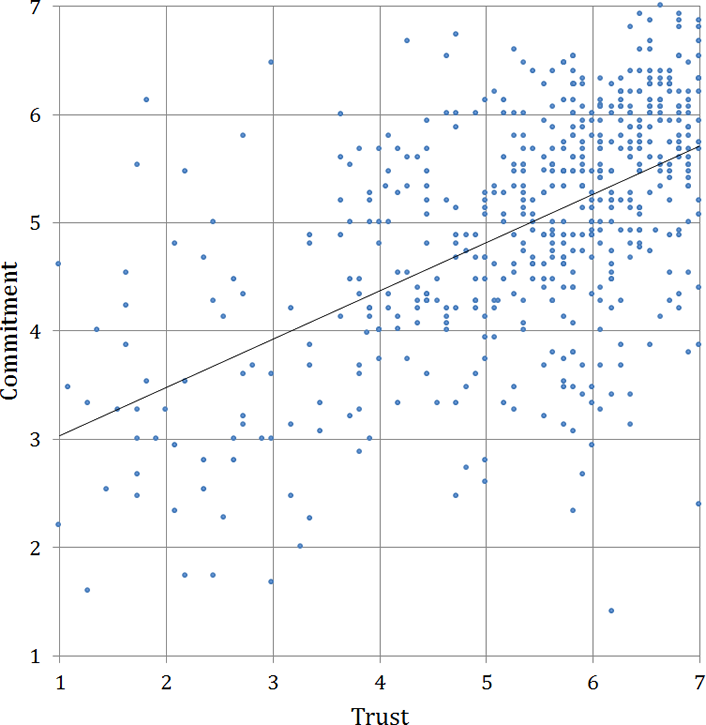

Finding 3: A strong connection exists between employees' trust in their supervisors and how committed or invested they are in their work and workplace. (See figure 3.)

Figure 3. Relationship between trust and commitment among IT personnel42

Leaders and Trust/Relationships

It's important to foster trust to drive change (and because it is the right thing to do). Identical behaviors are not always viewed or interpreted in the same way. What seems trustworthy to one might seem untrustworthy to another. Those who lead others and strive for transparency must understand which behaviors others associate with trustworthiness and then act on what they learn.

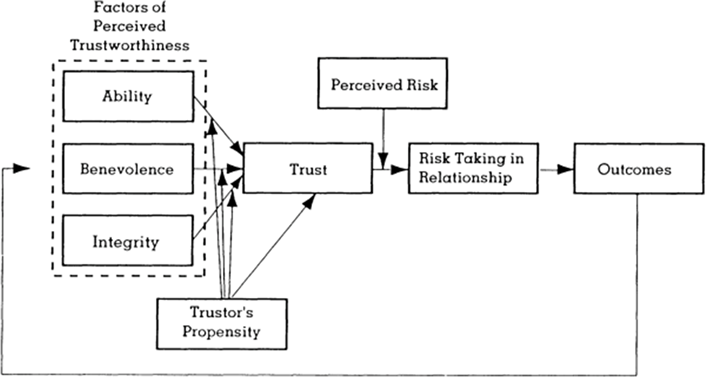

Although trust is a basic part of work and life, establishing and maintaining it can be a complicated and unpredictable process. One important trust model outlines several factors that contribute to a person's sense of trust in another; prime factors include the person's perceptions about the prospective trustee's ability, benevolence, and integrity.43 Such factors are tempered by the prospective trustor's propensity to trust and the perceived magnitude of the risk. As figure 4 shows, these factors are considered before any real action or risk taking occurs.

Figure 4. Model of organizational trust44

Clearly, trust can be subjective. Trust also has ramifications in many areas, including the costs of turnover and training, investment in a person's work/productivity, and a person's ability to work independently and take on new responsibilities. The degree of trust a person has in his or her supervisors and leaders affects how inclined that person is to stay with the organization.

Rachel Botsman shares a good example of this, pointing out that trust in an institution is increasingly shifting toward person-to-person trust.45 The implication is that relationships between individuals can have much to do with how we perceive organizations.

Although we cannot control others' trust in us, as with all the other variables here, we can at least practice behaviors and create environments that foster trust. Several types of behaviors can foster trust between supervisors and supervisees,46 including building solidarity, accepting influence, preventing misattributions, preventing disappointments, and bolstering self-confidence. In practical terms, creating mentoring or coaching opportunities, offering growth and/or lateral opportunities, and creating cross-functional experiences and opportunities for experimentation and collaboration all work toward greater transparency and trustworthiness.47

Individuals and Trust/Relationships

In building trusting relationships, all parties (leaders and followers alike) must clearly communicate expectations. This is the other side of the leadership coin: followers also have responsibility. An emerging discussion in organizational literature involves the notion of followership. Put simply, this notion embraces the idea that a relationship always includes at least two people and, while leaders have certain responsibilities in organizations, followers do as well. The relationship between leader and follower is crucial to reducing unnecessary turnover and fostering organizational, personal, and professional well-being. Although leaders focus on accountability, transparency, and other behaviors important to leadership, followers have a responsibility to act with integrity and communicate with their supervisors and leaders about the discrepancies, difficulties, frustrations, successes, and opportunities they observe. Increasing communication and trust among all parties increases investment in mutual success.

An example of this is the daily stand-up ritual I described earlier among personnel responsible for much of our IT department's support requests. In these daily stand-ups, everyone shares successes, challenges, and vulnerabilities — however large or small — which helps build stronger relationships and easier communications rather than "just lobbing [support request] tickets over the fence."48 In this example increased socialization and relationship building leads to increased trust. The key takeaway here is that, like trustworthiness, trust takes effort, and even subtle payoffs can be valuable.

Conclusions

This article offers a lot of information to digest, but there's also more to discover as we continue to explore factors related to how people in IT respond (and sometimes react) to change. One of the challenges and beauties of human behavior is that it varies. This variability gives us the chance to try new ways to help people adjust to the circumstances around them.

Building resilience; fostering trust; discovering new ways to exert influence; considering how we communicate with other individuals, groups, and organizations; and building community through rituals are only some of the factors to consider when working to build a culture responsive to change. Of course, the discussion here is not a comprehensive list of the organizational or individual factors that influence how people perceive change. It does, however, offer a first look at characteristics that affect responses to change and suggest ways in which those responses might be more efficient and effective. As we learn more about these issues, we can update our knowledge of how to manage the mental, emotional, and behavioral tax that change places on each of us and our organizations.

Learning more about ourselves and those around us, and then acting on the knowledge gained, offers concrete advantages. Although I have found this project gratifying, it will ultimately be useless if it does not result in practical improvements that make organizations better and individuals happier. It is challenging to gather, analyze, interpret, and report on such data, but the harder part is to discern what is useful and put it into practice in meaningful ways. The fulfillment of this second challenge rests with all of us as we look to meet changing and increasing client and customer demands — and keep our wits about us in the process.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to several individuals for their help with this project, including Mairéad Martin, senior director of ITS Services and Solutions at Penn State (now associate chief information officer at Tufts University), and Brian McDonald, president of MOR Associates, for their time and helpful feedback. I also appreciate constructive suggestions from a group of anonymous reviewers. For their interest and support, I thank Steve Fleagle, CIO at The University of Iowa; Kevin Morooney, CIO at Penn State; and John Harwood, associate CIO at Penn State. Finally, to Nancy Hays, EDUCAUSE editor, for her support and help in bringing this to pass.

Notes

- The EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues has been tracking the biggest concerns of IT leaders in higher education since 2000. As described in this article and elsewhere, many of the issues these reports document relate directly to how IT practitioners interact with and lead one another. Addressing these issues requires leadership and change among organizational members. We can all benefit from looking at how we interact with our colleagues at every level and in every organization so that we can address any concerns in the best possible way. It is in this spirit that I share this article. My hope is that the information it contains will be beneficial to leaders, followers, and colleagues alike.

- Jerry Luftman, Barry Derksen, Rajeev Dwivedi, Martin Santana, Hossein S. Zadeh, and Eduardo Rigoni, "Influential IT Management Trends: An International Study," Journal of Information Technology, vol. 30 (September 2015): 293–305.

- I conducted the first iteration of this research at the University of Iowa as part of my PhD dissertation, I.T. Changes: An Exploration of the Relationship Between Motivation, Trust, and Resistance to Change in Information Technology. The second iteration, presented on the Change and Motivation in I.T. website, involved participants from The University of Iowa and Penn State University.

- In this study, the average score was 3.22 on a scale of 1–7 (low to high resistance). Almost all populations in existing research that used the same scale averaged a lower score than 3.22. Participants in these studies included job applicants, undergraduate students, faculty, managers, and employees in the defense industry; employees in the housing, high-tech, manufacturing, and service sectors; and elderly individuals across a wide variety of cultures. This is an informal comparison; other studies have used the measure with a scale of 1–5 and 1–6. Although the results look consistent across these studies, I'm neither including them here nor stating that deeper analysis would not reveal more nuanced results. The purpose of this article is not to conduct a meta-analysis of resistance to change in academic literature, but rather to provide a comparison for the sake of providing perspective and bringing attention to solutions we can apply to concerns among those who work in higher ed IT. Study references are as follows: Alice H.Y. Hon, Matt Bloom, and J. Michael Crant, "Overcoming Resistance to Change and Enhancing Creative Performance," Journal of Management, vol. 40, no. 3 (2014): 919–941; Florian Kunze, Stephan Boehm, and Heike Bruch, "Age, Resistance to Change, and Job Performance," Journal of Managerial Psychology, vol. 28, nos. 7-8 (2013): 741–760; Shaul Oreg, "Resistance to Change: Developing an Individual Differences Measure," Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 88, no. 4 (2003): 680–693; Shaul Oreg, "Personality, Context, and Resistance to Organizational Change," European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, vol. 15, no. 1 (2006): 73–101; Shaul Oreg, Mahmut Bayazit, Maria Vakola, Luis Arciniega, Achilles Armenakis, Rasa Barkauskiene, and Nikos Bozionelos, "Dispositional Resistance to Change: Measurement Equivalence and the Link to Personal Values across 17 Nations," Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 93, no. 4 (2008): 935–944; Noga Sverdlik and Shaul Oreg, "Personal Values and Conflicting Motivational Forces in the Context of Imposed Change," Journal of Personality, vol. 77, no. 5 (2009): 1437–65; and Karen Van Dam, Shaul Oreg, and Birgit Schyns, "Daily Work Contexts and Resistance to Organisational Change: The Role of Leader–Member Exchange, Development Climate, and Change Process Characteristics," Applied Psychology: An International Review, vol. 57, no. 2 (2008): 313–334.

- Howard Baldwin, "8 Ways to Master Change Management," CIO Magazine, February 4, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Tina Kiefer, "Feeling Bad: Antecedents and Consequences of Negative Emotions in Ongoing Change," Journal of Organizational Behavior, vol. 26, no. 8 (2005): 875–897.

- Celine Bareil, "Two Paradigms about Resistance to Change," Organization Development Journal (Fall 2013): 59–71; and Eric B. Dent and Susan Galloway Goldberg, "Challenging 'Resistance to Change,'" Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, vol. 35, no. 1 (1999): 25–41.

- An influential and practical book on leading change is John P. Kotter and Dan S. Cohen, The Heart of Change: Real Life Stories of How People Change Their Organizations, Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

- I am grateful to Mark Linton, Matt Soccio, Mark Warren, and Ryan Wellar for sharing their experiences with the ITX program.

- Mark Warren, in discussion with the author, April 2015.

- Mark Linton, in discussion with the author, April 2015.

- Jerry I. Porras and Peter J. Robertson, "Organizational Development: Theory, Practice, and Research," in Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed., M. D. Dunnette and L. M. Hough, eds. Consulting Psychologists Press, 1992, 719–822.

- Anne Beaudry and Alain Pinsonneault, "Understanding User Responses to Information Technology: A Coping Model of User Adaptation," Management Information Systems, vol. 29, no. 3 (2005): 493–524.

- Ibid., 501.

- Ibid., 500–503.

- Mindy K. Shoss, L.A. Witt, and Dusya Vera, "When Does Adaptive Performance Lead to Higher Task Performance? When Does Adaptive Performance Yield Higher Overall Job Performance?" Journal of Organizational Behavior, vol. 33, no. 7 (2012): 910–924.

- Matt Soccio, in discussion with the author, April 2015.

- Sebastian Bruque, Jose Moyano, and Jacob Eisenberg, "Individual Adaptation to IT-Induced Change: The Role of Social Networks," Journal of Management Information Systems, vol. 25 no. 3 (2008): 177–206; Shaul Oreg and Yair Berson, "Leaders' Characteristics and Behaviors and Employees' Resistance to Organizational Change," Proc. Academy of Management, Meeting Abstract Supplement, 2009, 1–6; and Shaul Oreg and Noga Sverdlik, "Ambivalence toward Imposed Change: The Conflict between Dispositional Resistance to Change and the Orientation toward the Change Agent," Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 96, no. 2 (2011): 337–349.

- Although many of these suggestions can also be demonstrated with academic rigor, they were generated by IT managers and leaders during a presentation and discussion of practical steps that leaders and managers can take to respond positively to change and help others do the same. I thank my colleagues in the MOR Associates Information Technology Leadership Program, CIC2015 cohort, for generously sharing their ideas and experience (February 11, 2015).

- Matt Soccio, in discussion with the author, April 2015.

- Janice Beyer and Harrison M. Trice, "How an Organisation's Rites Reveal Its Culture," Organizational Dynamics, vol. 15, no. 4 (1994): 5–23.

- Gazi Islam and Michael J. Zyphur, "Rituals in Organizations: A Review and Expansion of Current Theory," Group & Organization Management, vol. 34, no. 1 (2009): 114–139.

- Ibid., 124.

- Karen Van Dam, Shaul Oreg, and Birgit Schyns, "Daily Work Contexts and Resistance to Organisational Change: The Role of Leader–Member Exchange, Development Climate, and Change Process Characteristics," Applied Psychology: An International Review, vol. 57, no. 22 (2008): 313–334.

- Aaron C.T. Smith and Bob Stewart, "Organizational Rituals: Features, Functions and Mechanisms," International Journal of Management Reviews, vol. 13, no. 2 (2011): 113–133.

- Henry Mintzberg, "We Need Both Networks and Communities," Harvard Business Review, 2015.

- Ryan Wellar, in discussion with the author, April 2015.

- Gretchen M. Spreitzer, "Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation," Academy of Management Journal, vol. 38, no. 5 (1995): 1442.

- M. Travis Maynard, Margaret M. Luciano, Lauren D. Innocenzo, John E. Mathieu, and Matthew D. Dean, "Modeling Time-Lagged Reciprocal Psychological Empowerment—Performance Relationships," Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 99, no. 6 (2014): 1244–1253; and Xiaomeng Zhang and Kathryn M. Bartol, "Linking Empowering Leadership and Employee Creativity: The Influence of Psychological Empowerment, Intrinsic Motivation, and Creative Process Engagement," Academy of Management Journal, vol. 53, no. 1 (2010): 107–128.

- Gretchen M. Spreitzer and David Doneson, "Musings on the Past and Future of Employee Empowerment," in Handbook of Organization Development, edited by Thomas G. Cummings, Sage Publications, 2008, 311–324; and Robert Quinn and Gretchen M. Spreitzer, "The Road to Empowerment: Seven Questions Every Leader Should Consider," Organizational Dynamics, vol. 26, no. 2 (1997): 37–49.

- Dirk Van Dierendonck and Maria Dijkstra, "The Role of the Follower in the Relationship between Empowering Leadership and Empowerment: A Longitudinal Investigation," Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 42, no. S1 (2012): 1–20.

- Lee G. Bolman and Terrence E. Deal, Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership [http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118573331.html], 3rd ed., Jossey-Bass, 2003.

- Ryan Wellar in discussion with the author, April 2015.

- Bolman and Deal, Reframing Organizations [http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118573331.html], 349.

- Julie Battilana and Tiziana Casciaro, "Overcoming Resistance to Organizational Change: Strong Ties and Affective Cooptation," Management Science, vol. 59, no. 4 (2013): 819–836.

- Wayne K. Hoy and Page A. Smith, "Influence: A Key to Successful Leadership," International Journal of Educational Management, vol. 21, no. 2 (2007): 158–167.

- Mark Warren, in discussion with the author, April 2015.

- Vanessa Bohns, "You're Already More Persuasive than You Think," Harvard Business Review, August 3, 2015.

- Martha Heller, "The CIO as Champion of Change," CIO Magazine, October 6, 2015.

- Steve Fleagle, in discussion with the author, Sept. 2013.

- Source: Author's collected data, April 2013. In the earlier data collection (June 2011) as a part of my PhD dissertation research, an almost identical relationship was found.

- Roger C. Mayer, James H. Davis, and F. David Schoorman, "An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust," Academy of Management Review, vol. 20, no. 3 (2008): 709–734.

- Ibid., 715.

- Rachel Botsman, "The Changing Rules of Trust in the Digital Age," Harvard Business Review, October 20, 2015.

- Frederique Six, Bart Nooteboom, and Adriaan Hoogendoorn, "Actions That Build Interpersonal Trust: A Relational Signalling Perspective," Review of Social Economy, vol. 68, no. 3 (2010): 285–315.

- Although many of these suggestions can also be demonstrated with academic rigor, they were generated by IT managers and leaders during a presentation and discussion of practical steps that leaders and managers can take to respond positively to change and help others do the same. I thank my colleagues in the MOR Associates Information Technology Leadership Program, CIC2015 cohort, for generously sharing their ideas and experience (February 11, 2015).

- Ryan Wellar, in discussion with the author, April 2015.

Nathan Culmer earned his doctorate in Education Policy and Leadership Studies with an emphasis in Higher Education Administration from The University of Iowa. He currently works as an instructional designer at Penn State University. His interests (research focused and otherwise) include change, motivation, technology, work relationships and how they affect the organization, and how people interact with one another and with technology. He enjoys meeting new people, learning new things, travelling, service projects, and spending time with his family. If you have inquiries about this article or the research conducted around it, he would be happy to discuss it with you. Please feel free to contact him at [email protected].

© 2015 Nathan P. Culmer. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.