Key Takeaways

- When no meaningful relationship exists between an educational technology and pedagogy, the tool itself loses value.

- We should start with a vision for our courses and curricula, and then identify the technologies or strategies that can help us achieve or further develop that vision.

- Open educational resources provide a relevant example of how pedagogy can point toward a richer way to integrate technology into our courses and our teaching philosophies, shifting to a student-centered approach to learning.

A few months ago, we gave a presentation where we poked fun at the educational technology industry's obsession with shiny new tools by suggesting that in addition to the learning management system (Canvas, Moodle, Blackboard), we'd soon be trying to find ways to use the cutting-edge technology of drones in our classrooms simply because they exist. Of course, that sarcastic opening would fall flat now, since it seems as if a new story pops up every day about how drones actually are being used in education.

One familiar example of an initially hyped ed tech tool that turned out to have a longer life cycle is the interactive whiteboard. A tremendous amount of money went to purchasing, installing, and training instructors to use a variety of "smart" boards in classrooms over the past 10–15 years. The widespread investment in the technology indicated that just about anyone could and would benefit from its presence in the classroom. Time has shown that in many cases, the technology has been massively underutilized. The reasons for this are numerous. While studies show this technology can positively affect learning outcomes, any positive effect relates primarily to how teachers use them. In other words, when no meaningful relationship exists between the technology and pedagogy, the tool itself loses value. Many instructors at our university use smartboards as dry erase boards, since they were installed in most classrooms without significant conversations with faculty about their needs or a thorough understanding of how faculty could use them to advance pedagogical goals. Without debating the merits of what drones or smartboards can offer a university, all of us need to rethink the relationship between technological tools and the pedagogies within which we embed them.

Faculty and administrators need to remember the motivations driving the adoption of technology in the classroom. New tricks and tools, shiny new apps and devices, should not motivate us to integrate technology into our courses. Instead, we should start with a vision for our courses and curricula, and then identify the technologies or strategies that can help us achieve or further develop that vision. PowerPoint presentations, for instance, will not necessarily further particular learning objectives just because we pack them with impressive animations or amusing photos. Reading slides word for word likely will not, either. The value is not in the tool, but in how the tool is used to achieve specific learning objectives. As much as it's possible for a tool to engage viewers and advance objectives, it's also possible for the tool to annoy viewers and impede learning objectives. A fine line divides a useful tool for communication and teaching from a tool that is, as Rebecca Schuman has called PowerPoint, "deleterious to the successful dissemination of knowledge."

Source: Schuman, Power pointless: Digital slideshows are the scourge of higher education

What motivates faculty and institutional decisions about adopting new tech tools and engaging in new tech-based initiatives? It's crucial that we understand how the drivers for ed tech influence the learning outcomes as we engage with technology in our classes.

Motivations for Technology Adoption: An Example

A good, and timely, example for discussing the motivations behind adopting classroom technology arises from the broad realm labeled open educational resources (OER). OER are free, digital, easily shared learning materials. Open licensing (usually with Creative Commons licenses) means that OER can be reused, remixed, revised, redistributed, and retained. In other words, OER is flexible, and it empowers faculty and students to work together to customize learning materials to suit specific courses and objectives.

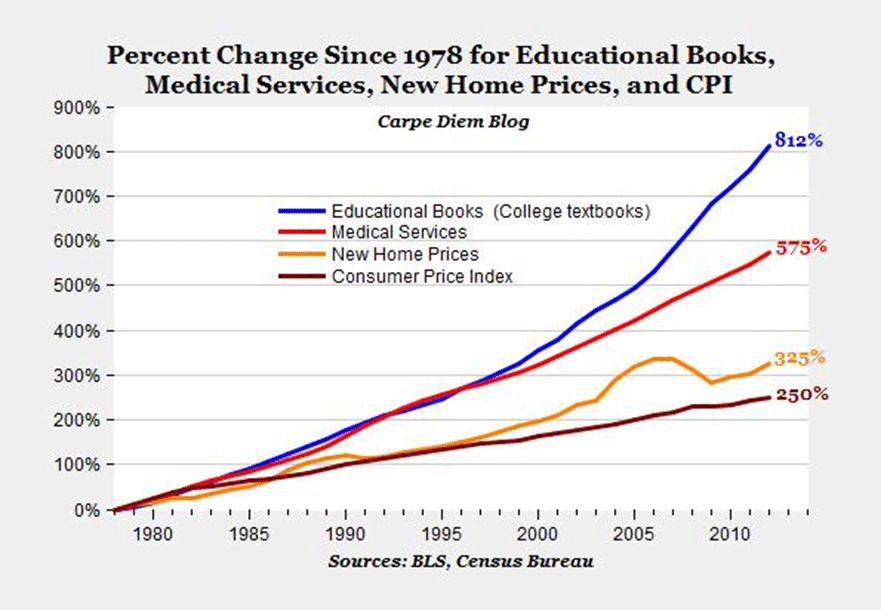

When you look at the majority of research and press about OER, they focus on the rising costs of textbooks and the phenomenal cost-saving potential [https://opentextbookalliance.org/] of OER. Individual students could save thousands of dollars over the course of an academic degree; colleges and universities could save hundreds of thousands — even millions — for their student bodies.

In addition, institutions stand to improve retention and enrollment rates by committing to OER initiatives. So should faculty convert to OER because it's cheaper? Should we adopt OER because the technology is easy to adopt? Or is something larger at stake here?

Cost savings and technical capabilities alone do not seem enough of a reason to encourage the widespread adoption of OER in contemporary higher education. There are lots of ways that schools can — and do — lower costs for students, but some of these approaches can negatively affect student learning. Our institution recently curtailed library hours (among other things) to address a serious budget deficit, for example; while perhaps necessary, it's not ideal. The fact that learning materials now exist in digital formats does not necessarily mean that these learning materials can compete with traditional printed textbooks or other analog tools in terms of helping students learn. We have probably all tried some new-tech way of doing some old-tech process and found that the old-tech way worked better. So what about OER makes them a good choice for adoption in the classroom?

A simple answer: the possibilities for pedagogical change that OER makes explicit. Student-centered pedagogy is clearly in fashion at the moment. But what does it mean to call an educational experience "student-centered"? In many cases, people seem to conflate student-centered pedagogy with a customer service model aimed at student satisfaction. Often, we hear "student-centered" trotted out in policy discussions aimed at eliminating bureaucratic obstacles for students (for example, making transferring credits between institutions easier), or in faculty conversations about teaching methods. In the latter, faculty often talk about increasing class discussion and refocusing classroom dynamics away from traditional lectures and toward a more interactive model. But in many cases, these new "student-centered" policies do little more than respond to market demand, and these "student-centered" pedagogies do little more than acknowledge a baseline student voice as part of the course. How can OER offer a more robust vision for centering our students in their educational experience?

By replacing a static textbook — or other stable learning material — with one that is openly licensed, faculty have the opportunity to create a new relationship between learners and the information they access in the course. Instead of thinking of knowledge as something students need to download into their brains, we start thinking of knowledge as something continuously created and revised. Whether students participate in the development and revision of OER or not, this redefined relationship between students and their course "texts" is central to the philosophy of learning that the course espouses. If faculty involve their students in interacting with OER, this relationship becomes even more explicit, as students are expected to critique and contribute to the body of knowledge from which they are learning. In this sense, knowledge is less a product that has distinct beginning and end points and is instead a process in which students can engage, ideally beyond the bounds of the course.

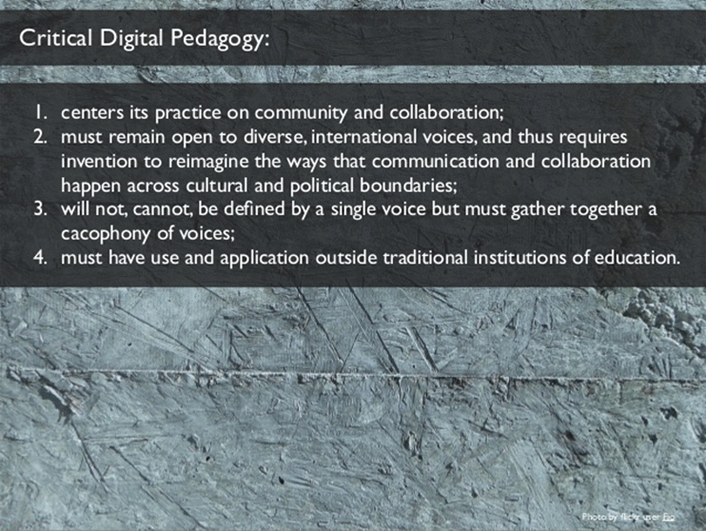

If texts — content — are at the heart of a course, and content is now shaped into a process that depends on learner engagement in order to function fully, then OER propels us into truly student-centered territory. This territory might more aptly be described as "learner-centered" or even "learner-directed" if we follow through on the open pedagogy toward which OER gestures. (For the purposes of this inquiry, this article defines "open pedagogy" in a way that remixes and revises the complex definition of "critical digital pedagogy" set forth by Jesse Stommel.)

Source: Stommel, Critical digital pedagogy: A definition

OER makes possible the shift from a primarily student-content interaction to an arrangement where the content is integral to the student-student and student-instructor interactions as well. What we once thought of as pedagogical accompaniments to content (class discussion, students assignments, etc.) are now inextricable from the content itself, which has been set in motion as a process by the community that interacts with it. Moreover, students asked to interact with OER become part of a wider public of developers, much like an open-source community. We can capitalize on this relationship between enrolled students and a broader public by drawing in wider communities of learners and expertise to help our students find relevance in their work, situate their ideas into key contexts, and contribute to the public good. We can ask our students — and ourselves as faculty — not just to deliver excellence within a prescribed set of parameters, but to help develop those parameters by asking questions about what problems need to be solved, what ideas need to be explored, what new paths should be carved based on the diverse perspectives at the table. Open pedagogy uses OER as a jumping-off point for remaking our courses so that they become not just repositories for content, but platforms for learning, collaboration, and engagement with the world outside the classroom.

Extrapolating the OER Example

OER is an excellent tool for thinking about the role of technology in higher education. Primarily enabled by the ability to freely share and modify materials in digital formats, OER seems like a technology-driven idea. But by finding our pedagogical motivations for using OER, we can mine the full benefits of what the technology makes possible. If we think of OER as just free digital stuff, as product, we can surely lower costs for students; we might even help them pass more courses because they will have reliable, free access to their learning materials. But we largely miss out on the opportunity to empower our students, to help them see content as something they can curate and create, and to help them see themselves as contributing members to the public marketplace of ideas. Essentially, this is a move from thinking about tech tools as finished products to thinking about them as dynamic components of our pedagogical processes. When we think about OER as something we do rather than something we find/adopt/acquire, we begin to tap its full potential for learning. The same lessons apply to any ed tech considered for adoption in the classroom. If we start with questions related to our vision, we can pull in the tools to help us realize it. What do we want to make? What do we want to do? How can our pedagogy be served by apps and gadgets (and not vice versa)? How can we hack them, adapt them, use them to enhance the learning in our classrooms? How can students use tools in unexpected ways to explore the questions that interest them? Technology makes so much possible. Let's be careful not to allow apps and gadgets to drive or limit where learning can go.

Ed tech is only as good as the vision we have for what education is and can be.

OER provides a relevant example of how pedagogy can point toward a richer way to integrate technology into our courses and our teaching philosophies. Surely many faculty are doing marvelous things with drones in the curricula. But the cutting edge in ed tech shouldn't align as much with the flashy new trick as with technology's ability to help us more richly collaborate with our students and more effectively share the fruit of those collaborations with the wider publics that our universities serve.

Robin DeRosa served as the University of New Hampshire OER Ambassador Pilot Consultant and is Plymouth State University Professor of English and Chair of Interdisciplinary Studies. She has a PhD in English from Tufts and undergraduate degrees in English and Women's Studies from Brown. She is an editor for Hybrid Pedagogy and recently served as a fellow at the Digital Pedagogy Lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Scott Robison is the director of Learning Technologies and Online Education and co-director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at Plymouth State University. Robison received his PhD in Instructional Technology from Ohio University. Current research interests include connected learning, technologies for public digital annotation, and issues around the "quality" of open educational resources.

© 2015 Robin DeRosa and Scott Robison. This EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY 4.0 International license