Design thinking focuses on users and their needs, encourages brainstorming and prototyping, and rewards out-of-the-box thinking that takes "wild ideas" and transforms them into real-world solutions.

Holly Morris, Director, Post-Secondary Model Development and Adoption, EDUCAUSE; and Greg Warman, Principal, Experience Point

Albert Einstein famously said, "No problem can be solved by the same kind of thinking that created it." So, assuming we agree, what exactly are our alternatives? How can we go beyond our standard approach to problems in higher education and entertain new possibilities? One promising alternative is to engage in design thinking.

Design thinking offers a creative yet structured approach for addressing large-scale challenges. In September 2014, we conducted an EDUCAUSE webinar, Design Thinking: Education Edition, and offered examples from our Breakthrough Models Incubator (BMI).

Here, we offer a summary of that webinar, discussing design thinking principles and process, describing real-world examples of design thinking in action, and offering possibilities for how you might introduce the approach into your own organization.

Defining Design Thinking

Design thinking was popularized by the Silicon Valley design firm IDEO, and its applicability to a wide range of challenges and solutions is presented in IDEO founder Tim Brown's book, Change by Design.

Design thinkers strive to balance what is desirable from a user's point of view with what is feasible with technology and viable from a business factors perspective.

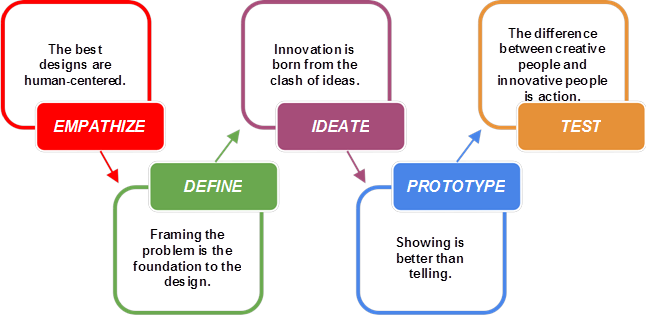

As figure 1 shows, this general overview of design thinking begins to reveal a bit about the five principles behind the approach and the process that brings them to life.

- The best designs are human centered. Putting human beings at the center of the process helps us create and maintain humanity as we innovate and move forward.

- Framing the problem is the foundation to the design. Starting with the right question(s) is everything.

- Innovation is born from the class of ideas. By grafting on to ideas and transforming ideas from different sources to fit our context, we get the best solutions. Rare is the transformative idea that emerges fully formed from one person or one source.

- Showing is better than telling. Experiencing solutions is far more engaging and illuminating than telling people about them. Think about how much more you learn from a sample of food than a description of it.

- The difference between creative people and innovative people is action. Live testing and iterating is what brings innovations to life. Without that essential step, there are just a lot of intriguing ideas.

Each of these principles translates into a process/action that brings it to life. We explore them below.

Figure 1. Design thinking's five principles

Empathy

By centering our work on users, we create empathy with them. With people for whom we feel a strong connection, it is easy to empathize because we know them in an intimate way — we know what they like and dislike, what they love, what makes them tired, what irritates them. With that knowledge, we know better how to meet their needs. With users, we don't typically have that sort of knowledge, and this deficit makes it difficult to design truly responsive solutions to their problems.

Achieving Empathy

Typically, when we seek to understand users, we turn to tools such as surveys and focus groups. Although these methods work well to provide a superficial level of knowledge, there are limits to surveys that block the development of empathy. One key challenge is that, sometimes, what people say they do and what they actually do can be quite different. It's not that people are deliberately trying to mislead; it's just that they sometimes "mis-remember." For example, when you ask students about their study habits in a focus group, they'll often describe their intentions rather than their actual behaviors.

One way to mitigate this tendency is to ask for specific examples about extreme scenarios. For example, if you want to understand students' experience with school, you might ask: "What was the absolute best experience you had in a class?" or "What was the worst experience you ever had studying for a test or working on a particular assignment?" Such specific, extreme examples can provide insight into how people truly respond to the conditions of their environment and lessens the impact of the social desirability bias (which more typically contaminates responses to general questions like, "What are your study habits?")

Another challenge with these tools is that we don't always know which questions are most relevant until we observe people in situ. For example, if we observe students studying during their subway commute, we'll instantly realize the need for questions specific to the environment's challenges — such as how they contend with the noise and crowding, and how they take notes while standing in a moving train — that might not occur to us if we're formulating the questions while sitting at a desk.

Observing people in context not only allows us to ask better questions, it also provides data that we can begin to triangulate on some of the thoughts and feelings that really motivate users. These methods allow us to know people at a level that enables responsive design.

Empathy in Action: An Example

Austin Community College (ACC), one of the BMI Teams for 2014, really embraced the challenge of getting to know their students in a different way and at different levels. Each of the team's eight members, including ACC's president, interviewed at least one (and, in some cases, several) prospective and current students; most interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes. During this time, team members asked students why they chose or were interested in ACC and what types of constraints they were experiencing. Also, because ACC is planning to develop a competency-based education program, they asked students about prior life experiences and what types of things they were looking for from ACC.

Team members came away with two interesting insights. First, they realized that the language they used sometimes alienated students. Team members often spoke in jargon; not only did this interfere with their connection with students, it led to misunderstanding about what ACC had to offer. Second, they learned how important it was to students that their instructors exhibit genuine care about them. Many of the students who had experiences with higher-profile institutions expressed their preference for ACC because of its faculty's concern for them. These findings are influencing how ACC team members approach both their marketing and course design as they develop their competency-based degrees.

Framing the Problem

The next step in design thinking is to frame the problem. This step is absolutely critical, because where you start a design challenge has much to do with where you end up.

Three Questions

We know that a great design challenge starts with a user focus. It should also be broad enough to give us the opportunity to innovate, yet narrow enough that we'll know where to start. To help frame the challenge, we suggest that you ask three simple yet powerful questions:

- Who is your user and what benefit are you trying to provide? This helps put the user at the center of your efforts.

- Why do you want to do this? This helps broaden the frame if it's too narrow.

- What's preventing you from doing it? This can help you narrow the frame to a reasonable starting point.

Although they might seem basic, projects often start with misguided assumptions that fall away once these three questions are seriously considered. The following example from a Stanford University design class shows this process in action, as well as how using real-world observation as a basis for answering these questions is key to design thinking.

Example: Stanford University

First, two key facts: in developing nations, about 4 million newborns die annually because they're born prematurely or otherwise have a low birth weight; the standard treatment — incubators — is cost-prohibitive for most hospitals in such nations. To address this challenge, a reasonable starting point seems clear: we need to somehow radically reduce the cost of incubators. In fact, this was the very challenge a non-governmental organization in Nepal gave a group of Stanford University students enrolled in the university's Design for Extreme Affordability class. This team, however, was using design thinking. So, they didn't simply accept that starting point.

Instead, they started with empathy, conducting observations at hospitals in Kathmandu. In so doing, they discovered three surprising facts. First, the hospitals already had many incubators. These incubators had likely either been donated or were older models bought at a discount. Second, most of the incubators were empty. When the students asked the doctors and nurses why, they learned the third — and most crucial — fact: many of the deaths of newborns were occurring in rural villages. Infants often died en route to the hospitals — assuming the parents could afford to make the journey (many could not).

With this burst of insight, the students immediately changed their research plan, heading out to these rural villages to learn more about healthcare services in context. Their work quickly revealed some critical user challenges:

- no reliable source of electricity;

- low literacy rates; and

- no reliable source of replacement parts.

With all of this experience in mind, the students completely re-framed their starting point. Rather than trying to develop an ultra low-cost incubator, they realized the true need was for an ultra-ultra-ultra low-cost way of keeping infants warm that required no moving parts, no electricity, and no instruction manual. Their final solution resembled a modern sleeping bag (infant-sized, of course), and included a remarkable innovation — a removable heating pad that, after warming up in boiling water, would release heat at a perfect 37C (natural body temperature) for four hours. The students formed a not-for-profit company around this product (Embrace Global) and to date have saved thousands of young lives.

Example: Montgomery Community College

Montgomery Community College's (MCC) initial goal when it joined BMI in 2013 was to give MCC students more/better literacy in three areas: finances, technology, and civics. Using design thinking, MCC redefined the project substantially. The team knew students were dropping out due to poor planning for how they would pay for college. Team members thus defined their challenge as: "How might we give students better information about financial planning for college?" Sounds reasonable, right? It was a good response to the question, and to the situation in front of them.

Their first answer was to offer a MOOC, which answered their problem and the institution's problems (a MOOC required no physical space or staffing increase). It would also be free for students. However, once team members employed design thinking and began truly focusing on the students, they saw that the problem wasn't a lack of information or even information quality.

Most institutions give students plenty of information about financial planning and financial aid. What MCC team members discovered from interviewing students and watching their behavior with respect to the financial aid system was that they were overwhelmed and discouraged, both by the amount of information and timing issues: students were unsure about what they needed to know and do at various points in the process.

This understanding helped MCC completely redefine their objective to: "How can we help students access the right amount of information, at just the right time." The reframing changed everything about how their solution developed. Instead of offering a MOOC or a class or a course, their solution delivered information in atypical ways, including running 30-second videos of critical topics in a loop on campus flat screens. These same videos are linked to social media outlets that provide information and lead to other sources and more complex amounts of information. Students can thus get into the information at the pace that they need and the time they need it. The team followed up by using analytics to map the precise places to plant their information and also determine how often they connected with students in each space.

All of this started because MCC was able to redefine the challenge through design thinking.

Brainstorming

The next step is ideation, or brainstorming. For those who have experienced bad brainstorms, the term can often elicit eye-rolls and deep sighs. However, with great preparation and discipline, brainstorms are an amazing source of small sparks that can combine and ignite into powerful solutions.

In this phase of the design thinking process, quantity is far more important that quality. Indeed, "bad" ideas often give rise to good ideas when they juxtaposed with other ideas and new options arise from grafting and modifying them.

Key Challenges and Solutions

Brainstorming sounds simple, but it's not easy. Our natural human tendency is to present small, safe ideas and spend a lot of time debating them down to something that is a half-step more exciting than the status quo. We end up with things that we've seen work before that don't take us much past where we are. But as Nobel Laureate Linus Pauling put it, "The best way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas." You must move away from the safe ideas; it's fine to catalog great ideas you're excited about, but don't fixate on them at the expense of ideas waiting to emerge. To encourage the development of ideas, there are some simple rules IDEO uses that you can use around brainstorming.

The Rules of Brainstorming

To create as much fodder as possible for the best possible solutions, IDEO has several rules for brainstorming:

- Defer judgment (on your own ideas and those of other people)

- Encourage wild ideas

- Build on the ideas of others

- Stay focused on the topic

- Have one conversation at a time

- Be visual (i.e. find a way to visually express your ideas)

- Go for quantity

The facilitator can play a big role in making sure everyone has the opportunity to have the floor and share their ideas; this, in turn, gives everyone else a chance to build on those ideas.

Although having "rules" here might seem counterintuitive, it helps formalize brainstorming and rescue it from a common view: that brainstorming is somehow a bit silly or ridiculous (even though we know it can generate good ideas and expand our thinking). Calling the session a "brainstorm" is also important; it communicates that you're wrestling with a challenge and it's time to assemble a diverse group of people to collaborate on possible solutions.

Example: Brainstorming in Action

At the EDUCAUSE webinar, we gave audience members a challenge: Imagine that you and 10 of your favorite people are designing a 21st century learning center. Use the brainstorming rules to figure it out. Among the chat-displayed responses? Get out of the building. No teachers. No walls. Community connections. Lots of writing space. Modular. Student-centered. And… holodeck.

The holodeck suggestion shows the value of the wild idea. Not that we'd actually implement one, but because it's possible to come up with an idea that honors the creative energy and creative leaps that "holodeck" inspires. As David Kelley notes, rather than staying grounded in existing or predictable ideas, brainstorming these "blue sky" ideas — things that will never work or that might, say, involve time travel or get you fired — gives you tremendous opportunity to pull the ideas back to the ground and come up with something truly innovative or different. In the holodeck example, we may choose to focus on one compelling aspect: the ability to live through a story rather than passively read about it. One can begin to imagine how, using inexpensive and pervasive technologies (rather than costly and somewhat difficult to access Star Trek devices), we can help users experience a scenario. Indeed, one of the authors of this article has sought to bring this dream to life via web-based simulations.

Prototyping

Next up is prototyping. Typically, in the ideation/brainstorming phase at many organizations, ideas are written on Post-It notes in a few words. In the prototyping phase, we expand on these ideas, taking them beyond the safe four corners of that small, yellow square. In the prototyping phase you will be taking a solution and making it multidimensional by creating another way to access it and show it to a potential user. That could be a storyboard (a series of scenes that take the potential user through the solution step-by-step, or a physical mock-up of a product or program to address a user need.

Storyboards are a relatively simple but powerful tool for moving an idea into a prototype; they are used frequently by the creative people at Pixar, the film studio that produced hits including "Toy Story," "A Bug's Life," and "Finding Nemo."

Conveying Ideas

The value of storyboards is that they move your idea beyond the Post-It note by

- creating a shared understanding of the story;

- exposing story flaws and things that just don't make sense; and

- inviting diverse teams to explore key aspects of the story.

Storyboards are just one way to achieve these benefits. You can also use simple sketches or handmade constructions. Other options include role playing and acting out user interactions, perhaps using video. All of these prototyping ideas help you take an idea from a few words on a Post-It note to something more meaningful that can help you and others think more deeply about an idea and how it might work.

Example: Ball State University

The design team at Ball State University did a fantastic job developing an app to encourage Pell Grant students to practice behaviors associated with higher retention and graduation rates. The team's application prototype consisted of basic student sketches.

They demoed the prototype to a small group of students to get immediate feedback. This small group session proved invaluable: it showed the team that students both liked working in pairs and wanted a leader board. The design team then decided to gamify the app. As this example shows, prototyping can offer invaluable insights that aren't available through other design tools.

Testing

In testing, you extend prototyping efforts into a live environment. Also, when you test, you're creating small invitations for real users to change their behavior and then learning from their responses. In so doing, you can convert some of your assumptions into knowledge.

No Failure

Discussing his own early efforts, Thomas Edison noted that, "I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work." That is, there's really no such thing as failure. In design thinking, testing doesn't use the scientific method; we're not testing to see if something is false or potentially true. Rather, a design thinking experiment is an attempt to grow your idea and figure out what you must do to ensure the idea's ultimate success.

Example: University of Maryland University College

The University of Maryland University College team used design thinking to develop their BMI 2013 Project: a pre-enrollment class called "Jumpstart." Jumpstart offers prospective students an opportunity to think through what they hope to gain by enrolling at UMUC and then use their insights and the college's tools to create personalized plans to a degree. Like the team at Ball State, these designers were quick to get a prototype up and running; they put it out for testing within three months of developing the idea. Because it's a short course, they've already been able to iterate on the course three times. This has given the team crucial feedback about how the course is working. They've found that students who take the course are far more likely to enroll, far more likely to carry over to the next semester, and typically have grade point averages almost 1.0 point higher than students who did not take the course.

Applying Design Principles Now

So, what can you do to start using design thinking right away?

- Introduce the user perspective into the conversation whenever you can. Think about the person or people buying your product or service and what they would want.

- Use the brainstorming rules. And brainstorm. Integrate the practice of bringing forward multiple ideas as much as you can.

- Seek inspiration through analogs. Look outside your department and outside higher education for successful innovations and think about how they might apply in your context.

The BMI 2013 teams benefitted tremendously from thinking about analogues as a way to kickstart their thinking. Successful companies like Weight Watchers (community and accountability) and E-harmony (selected matching to meet needs) provided teams with fresh ideas that ended up being the basis for successful projects.

And, finally, when all else fails, start again. Because you might do all these things and they might not work the first time — maybe people won't really want to look at it from the user's perspective or follow the brainstorming rules. At that point, your job as an innovator is to try again. And again, for as long as it takes to find that successful real-world solution based on your design thinking ideas.

© 2014 Holly Morris and Greg Warman. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 license.