Key Takeaways

- Quality communication between faculty and students in higher education is critical and considerably influences students' intellectual growth, but it is not easy to achieve, particularly when faculty teach large lecture courses.

- A feedback tool that provides substantive message templates for instructors, PassNote also includes links to specific resources that might help students with various tasks.

- PassNote's development focused on ease of use, openness (no login), and the ability to track usage to inform both tool improvement and future functionality.

At Purdue University Bethany Croton is an educational technologist, James E. Willis III was an educational assessment specialist (and is now visiting research associate at the Center for Research on Learning and Technology at Indiana University), and Jason Fish is director of Informatics.

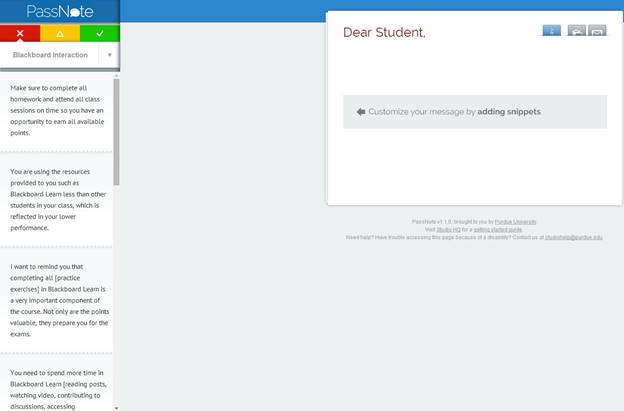

When Purdue University faculty asked for assistance in composing feedback messages to students, Information Technology at Purdue (ITaP) developed PassNote, a feedback tool that integrates good practice into the process of providing formative assessments. PassNote gives faculty customizable feedback prompts (snippets) and lets them connect students with information and links to services such as tutoring, Supplemental Instruction, library resources, technology tools, and workshops. PassNote "message starters" are often incomplete, allowing instructors to include course-specific information such as office hours and departmental resources. (See figure 1.)

Figure 1. A PassNote screen inviting message customization

Message construction in PassNote's library is based on our research about what students themselves find motivating, including positive feedback. Findings [http://www.itap.purdue.edu/studio/passnote/] include that

- Short messages are more effective in engaging students than longer ones.

- Using a first-person plural pronoun such as "we" helps students feel that the instructor cares about their success and is willing to assist them.1

- Providing specific resources and ideas for improvement is extremely useful for students.2

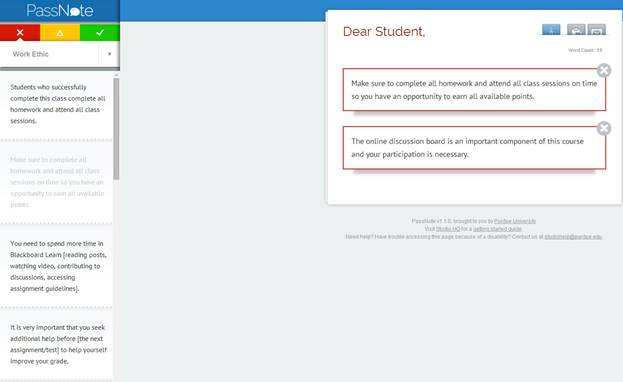

Students and instructors are not always aware of the tools available at a large campus such as Purdue. PassNote gives faculty a repository of available resources and readily suggests specific resources that are appropriate for students. Faculty members can send messages using whatever digital communication tool they prefer. The PassNote resource page [http://www.itap.purdue.edu/studio/passnote/] reminds faculty of good practice in sending messages to students, which can also help instructors promote self-directed learning (figure 2).3

Figure 2. A PassNote message focusing on work ethic concepts

PassNote is easy to use and does not require a login, making it attractive for instructors who are looking for inspiration in writing to students. The average user spends about two minutes on the site, indicating that instructors can find what they are looking for quickly.4 Although other schools will have different specific resources, some — such as tutoring and library services — are universal for most institutions. Also, the message topic headers, which include Blackboard Interaction, Attendance, Assessments, Resources, Work Ethics, and Encouragement, are easily transferable to nearly any instructional setting.

Feedback: Why and When It Matters

Communication between faculty and students is a critical element of higher education; student intellectual growth is quite often dependent upon effective feedback.5 What did the student do correctly? What could be improved upon in the next assignment? Most importantly, what is needed for academic growth and success?

Making Feedback Effective

The goal with faculty-provided feedback is to help students not only improve their skills, but also become more effective, self-directed learners.6 With small-enrollment courses, feedback is often personable and individualized, whereas in large lecture courses, contact time with professors is highly limited at best. Quite often, feedback in such courses is communicated only in terms of grades.

Although grades are an important indicator of student learning, they reflect static measures of performance on assignments and thus provide minimal context. Can we really expect students to interpret and translate what a B- means in terms of what content they did not understand, what improvements they need to make, or how they can better succeed in the course? In addition, feedback quality is an issue independent of student-professor ratios. Do comments such as "needs work," "reread pages 100–200," or simply "wrong" help students grow and deepen their understanding?

Timing within the educational experience is also a key to effective feedback. As Anna Rowe's research demonstrates, feedback within a student's first year of higher education supports decreasing attrition rates and can assist in giving students the support needed throughout their education.7 Regular feedback can also improve motivation, help students feel more connected with their instructors, and help reduce anxiety.8 International students, in particular, noted that feedback helped them combat the isolation they often feel when enrolled in large gateway courses.9

Composing and providing feedback that closes the gap between students' performance and what they need to do to perform better is not always easy for instructors. John Hattie and Helen Timperley's research in this field demonstrates that the most effective feedback relates to specific tasks and motivates students, while feedback such as "needs improvement" does not.10

So, we have two disparate issues here:

- students need content-specific, action-based feedback to improve their academic performance; and

- faculty need resources to go beyond "right and wrong" grading, thereby adopting more reflective feedback techniques.

In the latter case, the problem is time and effort. When professors are responsible for teaching lecture courses of 500 students, is it reasonable to expect them to offer individualized, content-specific, action-based feedback to each student? Instead, the target ought to be robust feedback, in which instructors are "reduc[ing] discrepancies between current understandings and performance and a goal."11 Effectively, the measure of good feedback is any information that can help a student close the gap between current knowledge and program learning outcomes.

The development, use, and refinement of learning analytics12 helps address and alleviate some of these problems, but the unresolved question is the quality of reflective feedback. Learning analytics help address formative feedback by staging digital interventions that give instructors the time to take action to help improve outcomes. A student might receive a warning for improvement, but without thoughtful direction, the possibility of success dwindles.

Types of Feedback

Students typically receive two types of feedback: formative and summative.13 Formative feedback provides measures of success and areas of improvement so learning can be reinforced; formative feedback during the course might include quizzes, tests, and written assignments. Summative feedback provides a measure of understanding through the entire course; the most common form of summative feedback is a final grade. Formative feedback helps a student progress successfully through a course so the summative feedback is optimized; the difference here is that formative feedback allows for alteration, regrouping, and change, whereas summative feedback is final.

Interestingly, previous research indicates that students respond very well to feedback in digital form.14 It also indicates that clear tone and wording of communications are related to student perceptions of fairness and their control over success.15 Hattie and Timperley see no distinction between teaching and feedback.16 Their meta-analysis across more than 7,000 studies17 suggests that providing feedback in multimedia forms is of the most effective ways to initiate positive results.18 When instructors' feedback directly relates to an individual problem and simultaneously builds on prior suggestions, the themes included in the correction help refine understanding.19

Learning from Feedback

The clearest way to see how students learn from feedback is to distinguish between giving feedback and grading.20 Grading is giving students information about how they performed on a specific assignment; it involves indicating what is incorrect and assigning an overall measure. Feedback takes grading into account, but its primary purpose is to affect a student's knowledge, skills, and dispositions so that work on future assignments is better than it would have been without the feedback.21 This creates the educational space for an intervention — providing resources, materials, and encouragement to achieve a successful learning outcome.

The problem of actually providing students with content-specific, individualized, and reflective feedback persists, however. It's also challenging to motivate students to become engaged learners and help them transition from high school to college students. Addressing these challenges remains a priority of digitalized feedback systems.

PassNote Development

During the development of PassNote, we focused on three principles. First, the website had to be easy for faculty to understand and use. We gave thoughtful consideration to PassNote functionality's design and implementation so that first-time users could get started without relying on help or "getting started" documentation.

Second, it was important to make the site open. Instead of requiring user login, PassNote is available to anyone, anywhere, and anytime simply by clicking the URL. This was important because it lowered the barrier of website entry for Purdue faculty and allowed for open use of PassNote's information and functionality. Developmentally, there was no reason to limit the tool's usefulness to only Purdue faculty when making it open caused no problems.

Figure 3. PassNote launch page

Third, it was important to know how the website was being used. We thus track selected PassNote message snippets to help further refine the tool and gather the information we need for improvements, new messages, and tool curation.

Although PassNote has been available for less than a year, future developments are already underway. New snippets are being written to provide a more exhaustive list to help faculty provide the appropriate feedback. One example of new functionality is the ability for users to provide feedback to us directly within the tool. This feedback might be about the website itself, additional research areas for investigation, or additional snippets that a user believes might benefit others. As PassNote's continues to grow, it remains important to keep student success as the website's core mission.

Although most current users are located on Purdue's campus, individuals have already visited the PassNote website from 59 nations around the world.22 People are beginning to discuss PassNote on Twitter23 and in other venues such as The Fourth International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge24 and the Annual Gateway Course Experience Conference 2014.25 Purdue plans to assess the tool formally, but because PassNote has been available for such a short time, more data collection is necessary before the assessment will be useful to meeting user needs.

Short demo of PassNote

Conclusion

PassNote is a tool designed to assist faculty with providing research-based feedback to students; our hope is that, in receiving better feedback, students will develop more advanced "error detection skills" in self-regulation and then deploy them in all areas of learning.26

Previous research on feedback highlights a multitude of obstacles, especially in providing communication to help students build on previous knowledge, constructing motivational and actionable responses, and creating pathways to additional support.27 Digital learning's added complexity demands a solution that builds on effective feedback. PassNote is a step forward in the ongoing effort to provide pragmatic applications to research findings, culminating in a practical solution that helps faculty provide thoughtful feedback.

- Patricia E. Gettings, Joseph Waters, Abigail Selzer King, Zeynep Tanes, and Matthew D. Pistilli, "Message Testing and Self-Efficacy in Course Signals: Formative Evaluation to Identify Effective Communication Strategies," paper presented at the Southern States Communication Association Annual Conference, Louisville, KY, 2013, p. 14.

- Gettings et al., "Message Testing and Self-Efficacy in Course Signals," p. 16.

- John Hattie and Helen Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," Review of Educational Research, vol. 77, no. 1, 2007, p. 86.

- Google Analytics, unpublished and unavailable to public webpages.

- Richard M. Felder and Rebecca Brent, "The Intellectual Development of Science and Engineering Students. Part 2: Teaching to Promote Growth," Journal of Engineering Education, vol. 93, issue 4, 2004, p. 280.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 86.

- Anna Rowe, "The Personal Dimension in Teaching: Why Students Value Feedback," International Journal of Educational Management, vol. 25, no. 4, 2011, p. 350.

- Rowe, "The Personal Dimension in Teaching," p. 347.

- Rowe, "The Personal Dimension in Teaching," p. 346.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 84.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 86.

- For a brief introduction to learning analytics, see George Siemens and Phil Long, "Penetrating the Fog: Analytics in Learning and Education," EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 46, no. 5, 2011, pp. 30-32; Kimberly Arnold and Matthew D. Pistilli, "Course Signals at Purdue: Using Learning Analytics to Increase Student Success," Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, 2012, pp. 267-270.

- Zeynep Tanes, Kimberly E. Arnold, Abigail Selzer King, and Mary Ann Remnet, "Using Signals for Appropriate Feedback: Perceptions and Practices," Computers & Education, vol. 57, no. 4, 2011, p. 2419.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 84.

- Joseph L. Chesebro and Matthew M. Martin, "Message Framing in the Classroom: The Relationship between Message Frames and Student Perceptions of Instructor Power," Communication Research Reports, vol. 27, no. 2, 2010, p. 160.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 82.

- "A more detailed synthesis of 74 meta-analyses in Hattie's (1999) database that included some information about feedback (across more than 7,000 studies and 13,370 effect sizes…) demonstrated that the most effective forms of feedback provide cues or reinforcement to learners…." Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 84.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 84.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 85.

- Rowe, "The Personal Dimension in Teaching," p. 350.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 86.

- Google Analytics, unpublished and unavailable to public webpages.

- David Jones, @djplaner, "PassNote from Purdue University itap.purdue.edu/studio/passnote—hadn't heard about this before. Captures some of what is missing in LMS tools," tweet, September 22, 2013.

- Stephen Aguilar, Steven Lonn, and Stephanie D. Teasley, "Perceptions and Use of an Early Warning System during a Higher Education Transition Program," Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (LAK '14), 2014, p. 117.

- Bethany Croton, "Using a Research Driven Tool to Provide Feedback to Students," Annual Gateway Course Experience Conference, 2014.

- Hattie and Timperley, "The Power of Feedback," p. 86.

- Zeynep Tanes and Patricia Gettings, "The Role of Computer-Mediated Instructional Message Quality on Perceived Message Effects in an Academic Analytics Intervention," paper presented at the International Communication Association annual conference, London, England (2012); Zeynep Tanes, Kimberly E. Arnold, Abigail Selzer King, and Mary Ann Remnet, "Using Signals for Appropriate Feedback: Perceptions and Practices," Computers & Education, vol. 57 (2011): 2414–2422; Kimberly Arnold, John P. Campbell, and Matthew D. Pistilli, "Signals at Purdue: Impacting Learning through Analytic Technology," paper presented at EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative Annual Meeting, Austin, TX (2012); and Patricia E. Gettings, Joseph Waters, Abigail Selzer King, Zeynep Tanes, and Matthew D. Pistilli, "Message Testing and Self-Efficacy in Course Signals: Formative Evaluation to Identify Effective Communication Strategies," paper presented at the Southern States Communication Association Annual Conference, Louisville, KY (2013).

© 2014 Bethany Croton, James E. Willis III, and Jason Fish. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No derivative works 4.0 license.