According to research into massive open online courses offered first by elite universities, the public narrative about MOOCs and those universities' goals do not align well.

Deke Kassabian is senior technology director, ISC Networking & Telecommunications, University of Pennsylvania.

When Stanford University opened two of their artificial intelligence courses to the public over the Internet in late 2011 — without credit and without charge — more than 100,000 people signed up. Leaders across higher education took notice.

During 2012, which the New York Times called "the year of the MOOC," massive open online courses went from virtually unknown to one of the hottest topics in higher education. Higher education insiders formed three major MOOC platform and distribution companies — Udacity, Coursera, and edX — and soon afterwards MOOCs began to appear from some of the top universities in the country. As of early 2014, the three largest MOOC providers have made more than 800 open online courses available, featuring the faculty and course content from more than 200 of the best-known universities in the world. Many millions of students have enrolled in these courses.

MOOCs quickly became the subject of hyperbolic claims ranging from how they would "save" higher education through improvements in student throughput and cost efficiency, to how they would "doom" higher education through the casualization of the faculty labor force, or even lead to the closing of universities crushed under disruption and unbundling effects previously experienced in other industries when the Internet profoundly affected their business models.

Through those early days, MOOCs appeared as feature stories almost daily in the higher education and popular press, while only slowly becoming the topic of research papers in scholarly journals. Some early MOOC commentators, such as Clayton Christensen of the Harvard Business School and Clay Shirky of NYU, described the potential for MOOCs to disrupt higher education while also helping with three of its biggest challenges: access, cost, and completion.1 MOOCs clearly provide an additional form of access to educational materials over the Internet. Whether MOOCs also help to manage or reduce cost by scaling up some college classes, or help with completion by leveraging MOOCs for advanced placement or other credit, is a matter for continued debate.

If enthusiasm for MOOCs in the early days was high, MOOC skepticism has grown just as rapidly. Previous large-scale online education efforts have failed, so it is reasonable to wonder whether MOOCs will turn out to be merely a higher education fad that will fade away.2 Certainly the many reports of low completion rates have shifted the MOOC narrative.3 In the language of the Gartner "Hype Cycle," 2011 and 2012 may have been the "peak of inflated expectations," while 2013 and 2014 may be the "trough of disillusionment" in which MOOCs don't turn out to be the silver bullet that neatly solves higher education's problems. A worthy question is whether MOOCs then follow the classic hype cycle and rise through a "slope of enlightenment" toward a "plateau of productivity."

Research I undertook in 2013 did not study higher education disruption through MOOCs, nor did it focus on questions such as the impact of MOOCs on faculty roles or their ability to foster good student learning outcomes. Those are important topics, and they influence and intersect with my research, but I had a particular focus in mind. Since 2012, many elite universities have invested time and money to develop MOOCs, but their motivations have not been entirely clear. The purpose of my research was to explore why.

Research Questions

- What do the elite, early adopter universities hope to achieve and learn by becoming involved with MOOCs?

- How will they assess progress toward those goals, and how will that inform their decisions on continued commitment?

- For those that plan an ongoing MOOC program, what return on investment or value proposition do they plan?

Methodology

For study sites, I looked to elite U.S. universities that have offered multiple MOOCs through major MOOC providers, selecting Columbia, Duke, and Harvard — each clearly an elite university and each an early adopter of MOOCs. At each site, I requested interviews with those involved in strategy development and decision making regarding MOOCs. I also requested interviews with faculty members involved in planning or teaching in the MOOC format, as well as faculty members willing to share their concerns and skepticism about MOOCs. Ultimately, I interviewed more than 40 people. At two of the three studied sites, I had the opportunity to directly observe relevant activities. At Columbia, I was invited to attend an early "flipped classroom," while at Harvard I sat in on a group meeting on research approaches to MOOC data from completed HarvardX courses. These observations contributed to my understanding of the evolving university culture around MOOCs.

Findings

The people interviewed for my study don't speak of MOOCs saving or disrupting higher education. Instead, they are interested in the more modest and reasonable potential of MOOCs to contribute to their mission plans in the areas of education and outreach, and to study the ways in which higher education might evolve in the Internet age.

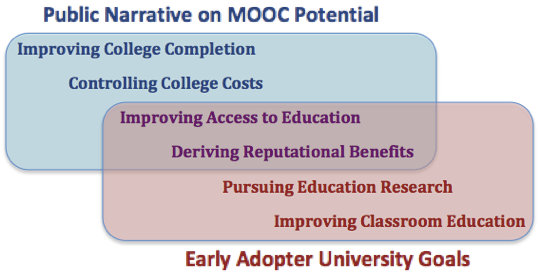

The three universities have goals that only partially match the MOOC narrative playing out in the press. MOOC themes commonly seen in the press include improved access to education, controlling college costs, and improving college completion, along with reputational benefits. The universities I studied express interest in improved access to education, but do not appear to focus on MOOCs as a way to achieve cost control at their own university or broadly within the higher education industry; they also do not focus on improvements to college completion through MOOCs.

The three universities have invested considerable thought into something less often discussed in the press: how education on their own campuses would benefit from their MOOC efforts. Both faculty members and those in senior administration with responsibility for MOOCs note that the faculty are now more engaged in discussing pedagogy and learning outcomes and that new teaching methods enabled by MOOCs (such as flipped classrooms), and lessons learned from engaging in MOOCs (such as the value of shorter lecture segments and more frequent testing for understanding), are being applied to residential education in interesting ways.

Universities' MOOC Goals

- Improve access to education

- Showcase university excellence, generally and for particular programs

- Advance teaching and learning through research

- Apply teaching and learning innovation to benefit residential education

Those interviewed admitted that it was still challenging to measure progress toward their goals. For instance, while progress on some of the above MOOC-related goals might begin to be measured by counting and characterizing student enrollments and completions or by counting publications of related research, measuring progress on other goals is more difficult. Officials at early adopter universities spoke of looking forward to gaining more experience in the short term toward developing better measures of goal progress in the future. All reported that they would continue their involvement in MOOCs for at least another few years and that the additional time might help them develop maturity in their ability to measure progress toward those goals.

A key finding of this research was that the goals of the elite, early adopter universities studied do not fully align with the public narrative. The studied universities are interested in improved and expanded access to education, but they are just as interested in teaching innovations and potential benefits to on-campus education. Other goals include providing more visibility for some of their educational programs and faculty and enabling more evidence-based education research, to gain a better understanding of how students engage with online course material and how they learn. Improvements to college completion and reducing the high cost of a college education were not goals — a finding that conflicts with the typical MOOC discussion in the press.

Figure 1. Differences and overlap between university goals and public narrative

Another finding of this research was that when it comes to MOOCs, the goals of university faculty and administration often differ. In interviews with members of the faculty, they emphasized improved access and outreach goals. University administrators also valued the access and outreach goals, but tended to emphasize improvement for residential education, the ability to motivate campus discussions on teaching and learning, and possible benefits to the university's reputation. Administrators also are likelier to focus on controlling MOOC production costs and achieving financial sustainability of their MOOC programs.

Financial Sustainability

Though none believed that MOOCs would provide a substantial revenue stream to their university any time soon, leaders at the early adopter universities raised the issues of cost recovery and financial sustainability.

Varied levels of initial and ongoing investment could be seen. Some early adopter universities appear to have made modest upfront investments and have more modest costs associated with their MOOC production, ranging from a few hundred thousand to about a million dollars per year — significant expenses, yes, but modest in the context of the overall budget of an elite private university with a large endowment. Other universities that made larger initial investments or that spend more each year to produce MOOCs are likelier to be interested in developing approaches to recovering costs and achieving financial sustainability of their MOOC programs.

Some of the revenue or cost avoidance opportunities associated with MOOCs discussed at Columbia, Duke, and Harvard involve possibilities such as small registration fees for all users or fees for identity-verified credentials (e.g., Coursera Signature Track), licensing of MOOCs for use by other universities, and reuse of MOOC course materials to support other university activities.

Financial return on investment aside, the early adopter universities in this study describe a significant value proposition in the form of benefits to on-campus and online education for credit. MOOC course videos can often be reused for credit-bearing online classes and can jump-start flipped classrooms by serving as part of the official course lecture content. MOOCs have also provided a natural way to bring more focus and attention to the campus conversations on teaching and learning.

MOOCs as a Research Opportunity

Some universities exhibit strong research interests when it comes to their MOOC goals. This was most evident at Harvard. Early research has involved learning theory and student engagement as well as questions involving who enrolls and who completes. Research on the value of peer and social network connections to student success has also started to emerge, as has research involving adaptive learning.

One clear opportunity enabled by MOOCs is the chance to more closely study teaching and learning practices for online and hybrid courses. Student participation data ("click data") from MOOCs is rich and becoming more so over time. With the large number of students involved in some MOOCs, and the opportunity to look at student success associated with different treatments in course design, universities have opportunities to rapidly identify and then put into practice approaches that work well. In some cases, the lessons learned will also translate into practices useful for traditional classroom education.

Conclusions and Observations

While MOOCs may not yet (and may not ever) be the "game changers" for higher education that some predicted, neither are they disappearing. On the contrary, their numbers continue to grow. The chance to pursue university mission goals through a high-profile development in higher education that simultaneously promotes university image, gives some members of the faculty a much larger audience, and is perceived positively by a public seeking increased connection with an otherwise exclusive university, is an opportunity too good for the early adopters to pass up.

The exuberance of 2012 has faded, replaced by the skepticism of 2014, but at the early adopter universities, MOOCs appear poised to play an important role in the higher education picture for at least the next few years, perhaps beyond, with a strong value proposition: supporting the goal of improving on-campus teaching and learning while also promoting the university and its faculty. At the same time, the elite universities connect with the public through educational outreach, demonstrating leadership in an emerging higher education learning technology.

- Clayton M. Christensen and Michael B. Horn, "Innovation Imperative: Change Everything — Online Education as an Agent of Transformation," New York Times online, November 1, 2013; Clay Shirky, "Napster, Udacity, and the Academy," Clay Shirky's blog, November 12, 2012; and Clay Shirky, "Your Massively Open Offline College Is Broken," The Awl, February 7, 2013.

- Taylor Walsh, Unlocking the Gates: How and Why Leading Universities Are Opening Up Access to Their Courses (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011).

- Andrew Dean Ho, Justin Reich, Sergiy O Nesterko, Daniel Thomas Seaton, Tommy Mullaney, Jim Waldo, and Isaac Chuang, "HarvardX and MITx: The First Year of Open Online Courses, Fall 2012–Summer 2013," HarvardX Working Paper Series No. 1 (January 21, 2014); and Laura Perna, Alan Ruby, Robert Boruch, Nicole Wang, Janie Scull, Chad Evans, Seher Ahmad, (2013, December 5). "The Life Cycle of a Million MOOC Users," presentation at the MOOC Research Conference, University of Texas, Arlington, December 5, 2013.

© 2014 Dikran W. Kassabian. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 license.