Key Takeaways

- Governments are pushing for systematic management and sharing of research data because of the clear benefits for the research community and the general public.

- Given this, publishers have begun to innovate in this space, even as some academic researchers resist the shift from existing models.

- The benefits of open data for researchers include increased visibility and citations, protection against fraud, and increased opportunities for collaboration; the key is to address researcher reservations and integrate better data management and dissemination practices into their existing workflows.

Mark Hahnel is the founder of figshare.

"Open data is data that can be freely used, reused, and redistributed by anyone — subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and sharealike."

— OpenDefinition.org

The success of open government data is indisputable. By empowering data scientists as well as the general public to interrogate publicly shared government data sets, we have been able to discover new trends and correlations as well as spot malfeasance. Open data affects publicly funded academic research at a governmental and funder level as well, including the types of research supported and what happens with the data collected. Nonetheless, it took a recent statement from the Public Library of Science (PLOS) to ignite the conversation about open data between individual academic researchers.

In that statement, issued February 24, 2014, PLOS said they expected their authors "to make available the data underlying the findings in the paper, which would be needed by someone wishing to understand, validate or replicate the work." The fact that this made front page news on the zeitgeist reddit happily surprised those of us working to disseminate academic content above and beyond traditional academic "papers." However, there was both confusion and disgruntled cries from academics, who thought that sharing their research data could harm their reputation if mistakes were found in their raw workings.

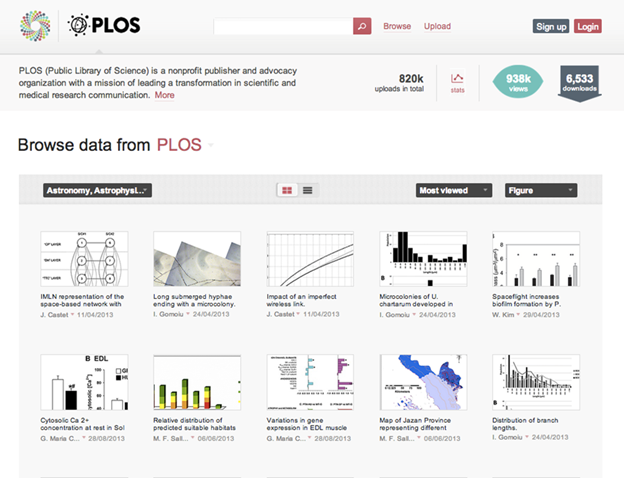

A screenshot from the Public Library of Science

Benefits of Open Data

Government agencies in the United States, European Union, United Kingdom, and elsewhere advocate for open research data. In the United States, for example, the National Science Foundation expects its funded researchers "to share with other researchers, at no more than incremental cost and within a reasonable time, the primary data, samples, physical collections and other supporting materials created or gathered in the course of work under NSF grants."1

Similarly, Neelie Kroes, vice president for the European Commission, stated that the EU "will require open access to all publications stemming from EU-funded research. That's why we will progressively open access to the research data, too. And why we're asking national funding bodies to do the same."2 This movement is following hot on the heels of mandates to open access to publications around the world. Thus, the Western world seems to be leading the way, while developing nations first negotiate open access publication mandates.

Governments are pushing for systematic management and sharing of research data for a simple reason: it has significant benefits for both the research community and the public as a whole. As the U.K.'s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council outlined in their 2011 update to their policy on research data,3 open data's benefits include that it:

- Increases the visibility of research and generates citations, leading to growth of the scientific reputation of individual researchers, their research teams, and their institutions

- Reinforces open scientific inquiry

- Protects against use of faulty data by allowing published results to be independently verified, refuted, or refined, thus improving the overall quality of research, encouraging diversity of analysis and opinion, and helping resolve scientific disputes

- Stimulates new approaches to data collection and analysis

- Increases awareness of research in related areas, leading to more opportunities for collaboration

- Allows for the reuse of research data in ways unforeseen by the initial investigators, which increases the efficiency of public funding use by avoiding unnecessary duplication of data collection

- Permits stronger data analysis by combining data from multiple sources

- Facilitates the education of new researchers and the wider public

As these benefits imply, making the products of their research openly available in the format they were created can help academic researchers avoid several existing challenges:

- Reproducibility. Research results are not considered valid unless other researchers can reproduce them. For example, C. Glenn Begley and Lee Ellis attempted to reproduce landmark cancer studies and confirmed the scientific findings in only 11 percent of cases.4

- Negative data. This is a self-perpetuating problem: If researchers base their hypotheses on published literature that contains false positives, they are wasting time and money and will inevitably produce further null data.

- Clinical trials. Researchers who do not publish negative data have a significant impact in clinical trials. Failure to publish this data has led to drugs with at best placebo — and at worst, detrimental — effects being released to the market (often at great profit).

- Fraud detection. With unreleased data sets, other researchers cannot verify the accuracy of the data used in a research study. (This factor also relates to reproducibility of research results.) With open data sets, data forensics can identify where data sets have been doctored or the data fabricated.

- Plagiarism. Use of another academic's data without proper attribution is difficult to detect if the raw data aren't available. With open data, a direct comparison is possible.

- Animal experiments. The "non-sharing" mentality among academic researchers has a big (but often unacknowledged) impact on research involving animals; when open data is available, researchers can evaluate and apply the results without conducting their own animal testing.

Resistance and Challenges

Despite such benefits — and the cries of moral and ethical victories in some quarters as the open data principle gathers momentum— the idea of open data meets resistance in other quarters.

Risks of Open Data

Some researchers claim that open data simply doesn't work for their research data. Rather than ignore these voices, it can help to isolate examples where open data will be problematic and address researchers in those areas as a community.

One interesting area here, for example, is genomic data. As technology develops to screen genetic data for markers of disease, many lives will undoubtedly be saved. At the same time, this data could also be used to discriminate against individuals because of their disease markers and subsequent phenotype. While in some countries insurance companies may not legally use this information for prejudicial reasons, personal data still has many unresolved issues. Among them are the levels of privacy individuals can legally claim (or expect) for use of their personal data by medical, business, or government organizations focused on healthcare, sales, and identification, for example.

Reward Models for Research

In the old model of reward, researchers applied for and received grants based on their reputations and the funding organization's interest in the proposed research. Publication of results could lead to improved reputation, further funding, invitations to present the results, consulting opportunities, and sometimes patents that could lead to new revenue when applied in the form of new business products. It's possible that we are now facing a backlash from academics who lack the desire to move research in a new direction — and away from the established, well-understood model of academic reward.

Surely there are enough researchers competing for funding to prompt a shift to a different reward model, one where academics compete for funding of research projects that will have an impact on all of their research outputs, data included. Consider the fact that, in the U.K., only 0.45 percent of all PhD students progress to the level of principal investigator. I was fortunate enough to have five postdoc fellows acting as my mentors when I started my PhD; by the time I finished, only one remained in academia. The other four would say that there were more than enough scientists to conduct research, but not enough funding. In such a competitive landscape, funders incentivizing researchers by giving them credit for all of their research outputs could help lead to a new completely open publishing future.

Support and Next Steps

Organizations such as the Research Data Alliance (RDA), the Committee on Data for Science and Technology (CODATA), and Force 11 have been discussing these issues and benefits for nearly 50 years (in the case of CODATA). However, while they are all open communities, few working researchers are actually involved; the majority of stakeholders are publishers, funding bodies, and developers working on tools to better manage research. It is therefore somewhat frustrating to see researchers populating mainstream blogs and Twitter accounts with questions about how to implement open research outputs in their fields, as if they are the first to have considered this challenge. However, this frustration is quickly overcome by the fact that their late-developing attention to this issue — which is hugely important in academia — is now making it a much bigger topic of conversation.

Because open access has created huge changes in the academic publishing world, it is no surprise that publishers are looking to innovate in this space. As well as PLOS's previously mentioned new policy on the releasing the data behind the research paper, eLife editor — and 2013 Nobel Prize winner for Medicine and Physiology — Randy Sheckman also issued a recent call to arms on the topic. eLife is a two-year-old open access journal funded by the Wellcome Trust, Max Planck Society, and Howard Hughes Medical School. Upon winning the Nobel Prize, Sheckman called on the academic community to avoid publishing solely in journals with high impact factors, such as Nature, Cell, and Science. Sheckman reasoned that we should be publishing all research — not just that which is novel, but that which is logical and methodical so as to make the research process more efficient, whilst at the same time giving the tax payers who funded the research, value for money.

Researchers have been quick to react to such statements; indeed, in this case many accused Sheckman of hypocrisy and said he was "pulling up the ladder" (he himself has 146 publications in these three journals alone). However, the fact that the publishers are getting positive reactions for their activities in this space, supporting open data, might be because academics deal with publishers much more often than with funders; a single five-year funding grant could spawn tens of papers looking to be published for example.

Conclusion

Based on current trends, all academics will at some point have to make their outputs available. PLOS and others are making the effort to move things forward at a faster pace. The end goal is to make research more efficient, and yet in some quarters open data is still regarded as a bad thing. Do life scientists think that making their own gels instead of purchasing them ready to use is a good thing? Of course not — so what is the problem to which they object?

Academic institutions and funding bodies must ensure that all academics for whom they are responsible are aware of several facts:

- Sharing detailed research data is associated with an increase in citation rate.5

- A diverse range of metrics can be tracked, demonstrating impact at many levels.

- The intensity of data set reuse has been steadily increasing since 2003.6

- The technology exists to allow researchers to make all of their research outputs available openly online, in a time-efficient manner.

- The academic reward system is changing, so that all research outputs are treated as valuable contributions to research, not just papers.

By mandating that all publicly funded research be made openly available, governments have ensured/communicated that the data sharing practice should become integral to the scholarly workflow. If so, the power in linked open research data should give private research bodies evidence that open data can have enormous economic and societal benefits for everyone.

- US National Science Foundation, "Chapter VI — Other Post-Aware Requirements and Considerations," Award and Administration Guide, January 2011.

- Opening up Scientific Data Speeches, Neelie Kroes, vice-president of the European Commission responsible for the Digital Agenda. Launch of the Research Data Alliance, Stockholm, 18 March 2013.

- EPSRC, "New policy on research data," Connect, Issue 82 (19 May 2011).

- C. Glenn Begley and Lee Ellis, "Drug Development: Raise Standards for Preclinical Cancer Research," Nature, vol. 483, 2012, pp. 531–533.

- Sharing Detailed Research Data Is Associated with Increased Citation Rate, Heather A. Piwowar, Roger S. Day, Douglas B. Fridsma, (2007) "Sharing Detailed Research Data Is Associated with Increased Citation Rate," PLoS ONE vol. 2, no. 3 (2007): e308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000308.

- Heather A. Piwowar, Todd J. Vision, "Data Reuse and the Open Data Citation Advantage," PeerJ1 (2013): e175.

2014 Mark Hahnel. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.