Today's IT leaders need a different set of skills than their predecessors to thrive in an era of commoditized and democratized technology. Collaboration, innovation, and strategic alignment with institutional goals are essential to their own success — and that of their institutions — particularly in a time of profound budgetary challenges.

Michael Kubit is interim chief of operations, Information Technology Services, Case Western Reserve University.

What does an IT manager need to lead in this new reality, where IT professionals no longer possess all the knowledge and expertise? How do we learn to influence events on our campuses without positional authority? What skills and competencies are required to lead cross-institutional collaboration? How do we change organizational culture? How will our organizations learn to maintain existing service levels, while trying to keep pace with the accelerated growth of expectations — and with declining or (at best) static budgets?

These are not traditional IT leadership challenges: IT leaders must develop a new set of skills. Emotional and social intelligence, the ability to provide leadership through ambiguity, managing behavior as performance, and effective engagement of stakeholders are the critical skills for IT managers today.

The rapid pace of technological change demands IT organizations that are agile, responsive, collaborative, and aligned with the priorities of the institutions they serve. Simultaneously, universities exist in a digital world where technology is ubiquitous and constantly changing. Escalating costs, decreased funding, rising demand, increased regulations, broader access, and dated practices create both challenge and opportunity. An institution's response to these opportunities will require IT organizations to take on a new role. Are we capable of supporting the use of IT as a strategic resource, rather than simply infrastructure? In many cases, fundamental changes are required for IT organizations to maintain relevance. These realities require a new type of organization and, more importantly, a new approach to leadership.

At the same time, CIOs and other leaders within higher education view with concern the potential lack of IT leaders capable of helping our organizations move forward. The latest CIO report from the Center for Higher Education Chief Information Officer Studies (CHECS)1 indicates that nearly half of current CIOs plan to retire within the next five to ten years. Do we have sufficient numbers of potential leaders in the pipeline? And are they gaining the requisite new skills along the way?

Current Context

Historically, the use of information technology focused largely on infrastructure and enterprise business applications. Today, IT organizations need to find ways to align more closely with the teaching, learning, and research missions of their respective institutions. Three of the EDUCAUSE Top Ten IT Issues for 2014 emphasize the support of technology in the teaching and learning mission. The remaining issues involve positioning information technology as a strategic asset to leverage as a vehicle for innovation.

Students today have growing expectations of technology and assume it will be readily available to support all aspects of their lives. Infrastructure, although considered a utility, faces exponentially increasing demand. IT organizations must learn to innovate in response to the institution's needs, yet the pace of change requires an ability to respond with a new agility. How do IT managers respond to these opportunities with existing staffing and resource levels? Substantial gains in operational efficiencies are possible by addressing the "churn" caused by unhealthy characteristics within an organization's culture, but first they must be identified.

Historical Perspective

The last decades of the twentieth century focused predominantly on building infrastructure. We deployed mainframes and built the data centers in which they resided. We built networks to accommodate the emergence of the personal computer. We transitioned away from mainframes into distributed server and storage environments. Highly talented IT professionals who built and maintained this technology became "high-priests" of this burgeoning industry. Highly specialized knowledge, highly restricted access, and the need to build marked an era in which infrastructure ruled.

As IT organizations grew, so did the need for new managers. Quite naturally, we looked to those who led in the creation of our newly created infrastructures. However, institutional compensation models force-aligned salary with number of direct reports, creating a situation in which the only way to provide a higher level of compensation was to promote subject matter experts to management positions. Technology-focused managers maintained subject matter expertise in their role as manager, and many organizations did not provide professional development to aid the transition into enterprise leader.

From Subject-Matter Expert to Leader

Individuals moving from the role of subject matter expert to manager face two difficult challenges. The first is to shift focus from how something gets done (process) to what gets done (outcome). The second involves the transition from being a manager of things to a leader of people. Without a successful transition, a manager continues to lead from a position of knowledge and exercises too much positional power and control over decisions that should be made by their team. Over a period of time, this creates a situation in which teams could become overly dependent on their manager for information and direction, often leading to an unhealthy relationship that resembles co-dependency.

A 2004 Harvard Business Review article presents information on leadership and the phenomenon of transference,2 first witnessed and described by Sigmund Freud. The article describes how a manager-subordinate relationship can exhibit characteristics of a parent and child. Typically, the role of a parent is to provide permission, security, resources, advice, and criticism — to give. Conversely, children are dependent, emotional, and reactive — they take. In an organization in which managers lead from a position of knowledge, the typical dialogue between a manager and subordinate resembles the dialogue between a parent and child. The manager "advises" the team on all aspects of a project or initiative, leaving little room for contribution. This leads to a sense among the team that you have to learn the manager's "right" way of doing things. Long-term consequences from this style of management include teams that are reactionary and overly dependent and have lost the ability to innovate.

Functional Silos

One of the most disruptive aspects of any organization can be the emergence of functional silos. Overemphasis on the leader's functional knowledge, coupled with a natural tendency toward implicit association among team members, enables the growth of multiple cultures within the larger organization. Top leaders do not perceive themselves as a team. They draw affinity from their relationship with their functional area, rather than focusing their attention upward and outward and building relationships with their peers. If an organization cannot work effectively within itself, will it be able to effectively provide the kind of collaborative integration required by colleagues across the enterprise? An over-reliance on functional knowledge in leadership positions will lead to an aversion to risk. What is the team's reaction when challenged with a new opportunity, or when facing an unexpected outcome? If they exhibit an inability to accept responsibility, clearly a lack of teamwork exists along with a culture that does not recognize mistakes as learning opportunities.

Open to Learning

Managers need to become comfortable with the ambiguity that accompanies an increased level of responsibility and must develop the ability to make decisions with as little information as possible. Paralysis by analysis clearly impacts agility.

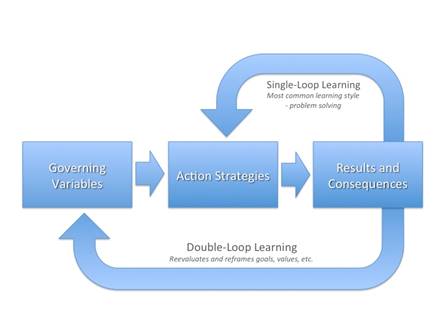

An organization's ability to learn is also impacted by dated management practices. Chris Argyris's work on organizational learning notes that the process of learning involves detecting and correcting error. Error, in this context, is any feature of knowledge or knowing that inhibits the organization's ability to learn. The typical approach involves connecting a tactical strategy with a result. If we do not achieve the results we expect, we analyze the results and try a different approach. Considered single-loop learning,3 this approach can be problematic in an organization in which decisions are made top-down, or in a risk-averse environment in which people do not feel comfortable sharing all the information related to a failed execution strategy.

What Next?

Until now, many of these legacy practices would not prevent an organization from functioning and producing positive outcomes. However, the disruptions facing higher education and the impact on information technology will affect every institution in a unique way. Additional resources will be scarce and difficult to obtain. We need to find ways to increase organizational effectiveness. Understanding leadership and its impact on organizational behavior is key to creating this capacity.

New Models

New models call for organizations that are networked, flat, flexible, diverse, and global. Position power no longer suffices. Organizations need leaders who can navigate their organizations through a network of relationships rather than relying on their positional authority to "drive" change. Leadership's role is to provide vision and align direction while actively influencing, motivating, and coaching others toward the continued and sustained development of a high-performing organization. The best leaders are ones who can call on the particular set of skills appropriate for a given situation.

Ultimately, the effective mastery of critical leadership competencies can transform organizations and enable high-performing environments where individuals feel productive, fulfilled, and engaged. Teams functioning in this manner can transform the organizations we serve and truly make an impact during this time of disruptive change.

Transforming the Organization

Information Technology Services at Case Western Reserve University has been maturing through the process of transformation, from an organization primarily focused on technology to one focused on service and innovation. Moving from an inward focus to an external focus is not easy. It requires changing the culture, and changing the culture of an organization is not for the faint of heart. "Culture eats strategy for breakfast" is a remark attributed to management consultant, educator, and author Peter Drucker. Culture is typically defined as a combination of values and behavior. A strong culture flourishes with a clear set of values and norms that actively guide the way an organization operates. Culture reflects leadership. If you want to change your culture, start at the top.

Many organizations misdiagnose the challenges they face and often attempt to address the issue through reorganization. On closer inspection we might find multiple cultures within the organization, which means starting with the leaders. The following steps outline a process that helps accomplish this change.

1. Define the Role

The Konosuke Matsushita Professor of Leadership, Emeritus, at the Harvard Business School and New York Times best-selling author, John Kotter, identifies the first step in leading successful change initiatives as creating a sense of urgency.5 In other words, point out the issue and allow others to understand the need for change.

What we discovered at Case Western Reserve was that our management team did not have a clear understanding of what was expected of them as managers and, more importantly, what was expected of them as leaders.

People First. Fundamentally, managers are being asked to shift attention from managing things to leading people. It is critically important for those who manage direct reports to recognize that relationships with staff, peers, colleagues, and senior leaders are their primary responsibility. Managers are expected to pay attention to the professional development goals of each member of their team. Effective leaders are emotionally and socially intelligent. Emotional and social intelligence is the capacity for recognizing our own feelings and those of others, for motivating ourselves, and for managing emotions effectively in ourselves and in others. It describes the behaviors that sustain people in challenging roles, or as their careers become more demanding, and it captures the qualities that help people deal effectively with change.6

Raise Your Perspective. As leaders in the organization, a good rule of thumb is to spend half of your time managing your team. The other half should be spent building relationships with peer managers and colleagues from across the university. Managers are responsible for the collective success of the division, not just their team. We stressed the importance of understanding that the success of a division is evaluated as one entity, not by narrow functional area. We collectively own our successes, as well as our opportunities to improve.

In his Harvard Business Review article, "How Managers Become Leaders – The Seven Seismic Shifts of Perspective and Responsibility," Michael Watkins provides insight into the changes in leadership skills and focus that an individual must navigate in order to become a successful enterprise leader.7

- Specialist to generalist: An individual's most difficult challenge moving into a new role has to do with shifting from leading a single function to overseeing a set of business functions. Adapting to the new responsibilities can be both difficult and challenging. Therefore it is imperative that a new leader avoid over-managing the most familiar functions and undermanaging the others. The new leader must learn and understand the new mental models, tools, and terminology used in the functions of new areas of responsibility.

- Analyst to integrator: When moving into an enterprise leadership role, it is critical to learn how to manage and integrate the collective knowledge of cross-functional teams in order to solve important organizational problems.

- Tactician to strategist: After spending a good portion of their careers learning how to be tactical, enterprise leaders must shift their focus to become more strategic by developing the ability to shift between details and the larger picture, perceive important patterns in complex situations, and develop the ability to visualize outcomes and how key stakeholders will perceive them.

- Bricklayer to architect: Enterprise leaders need to know the principles of organizational change and change management, including the mechanics of organizational design, business process improvement, and transition management.

- Problem solver to agenda setter: Many managers are promoted to senior levels because of their ability to fix problems. Enterprise leaders must focus less on problem solving and more on defining and prioritizing which problems the organization should address.

- Warrior to diplomat: Leaders must learn to use the tools of diplomacy — negotiation, persuasion, conflict management, and alliance building — to help shape the business environment in support of strategic objectives.

- Supporting cast member to lead role: Learn to demonstrate the right behaviors and remember that as a leader you are now a role model for the organization. People pay a lot of attention to what leaders say and do, as well as what they don't say and do. Leaders must learn how to lead and effectively communicate both directly and indirectly.

2. Change the Approach

Organizational agility requires a level of responsiveness not possible with traditional structures and a formal hierarchy. Every member of the team must be empowered to make decisions and directly contribute to a positive outcome. Managers must let go of control and shift their focus to empowerment. Does the team have a clear understanding of expectations? Does the team have the resources needed to succeed? Do any obstacles require attention? Leaders maintaining the proper distance from day-to-day operations and empowering staff to make decisions help the organization take on a new learning style. Clarity often comes from examining issues from multiple perspectives. Teams should be empowered to look beyond the cause and effect of single-loop learning and develop a more sophisticated approach to engaging with an issue. Goals and conceptual frameworks can be reassessed, along with values and expectations. This double-loop learning enables a broader perspective (see figure 1). At Case Western Reserve, we regularly emphasize the importance of continuous improvement and data-driven decision making.

Figure 1. Explanation of single- and double-loop learning

According to Argyris:

The underlying aims… are to help people to produce valid information, make informed choices, and develop an internal commitment to those choices. Embedded in these values is the assumption that power (for double loop learning) comes from having reliable information, from being competent, from taking on personal responsibilities, and from monitoring continually the effectiveness of one's decisions."8

Relating this back to the earlier example of manager-as-parent, the goal is to position the manager-staff relationship as an adult-professional relationship. Treating our colleagues as adult professionals raises the level of performance by addressing entitlement and encouraging a culture of accountability.

3. Align the Leadership

Organizational alignment is critical in order to be agile and responsive. Getting the organization focused on the right priorities is the role of leadership. Therefore, getting the leadership team aligned is critical. What are the actions that can be taken at the executive level to help mature an organization's learning style and enable the ability to respond quickly to institutional needs?

Develop a Plan: Having a strategic plan that aligns with the institution's strategic plan is a critical first step. However, the challenge faced by many organizations appears when it comes time to "operationalize" the strategic plan. Rather than delegating goals and objectives in a top-down approach, this assignment is given to managers, who are asked to develop quarterly goals and objectives that align with the themes found in the strategic plan. They determine the scope of each goal, the resources required, the timeframe for completion, and the overall prioritization of goals and objectives across the entire division. Projects are prioritized using a scoring rubric that applies prioritization criteria. Having a clearly defined set of priorities enables the organization to focus on what is strategic and removes any ambiguity around prioritization of work.

Get on the Same Page: Another critical element in building agility is developing a uniform culture. For this to happen, it is vital that the leadership team be unified on critical organizational elements. Case Western developed an Organizational Playbook that would allow us to ensure the executive and senior leadership teams align on the high-priority expectations related to managing people, processes, and projects. Additionally, it would allow us to determine the organizational components necessary to create a uniform organizational culture around a set of behavioral norms:

- Fundamentals of Leadership

- Fundamentals of Managing People

- Fundamentals of Managing Process

- Fundamentals of Managing Projects

The organizational components identified in each category serve to clearly articulate a set of expectations across the IT division. Education and training materials were developed, and the division now has clear expectations and holds itself accountable for delivery. From a leadership perspective, it empowers managers to focus on outcome rather than process. As an organization matures in its learning style, it is not unusual to fall back into single-loop learning behaviors and start following processes without a full understanding for why the process exists in the first place. New learning takes place when the team decides to modify the process in order to insure better outcomes.

Conclusion

Helping leaders understand the imperative to change is difficult. It requires them to let go of their functional knowledge and take on the role of leader. The mental model and example from nature that might help us better understand this notion of organizational agility and responsiveness can be seen in the flocking behavior of starlings, known as a murmuration. Don Tapscott, in his 2012 TED talk, introduced this concept by relating it to a number of organizational principles.

"… there's leadership but there's no one leader. Is this some kind of fanciful analogy, or could we actually learn something from this? ...This is a huge collaboration. It's an openness and a sharing of all kinds of information not just about location and trajectory and danger and so on, but also about food sources. There is a real sense of interdependence of the individual birds somehow understand that their interests are in the interests of the collective."

How do we create an organization that responds more like a murmuration of starlings than the familiar V-shaped flight formation of a flock of geese?

Image taken by Adam, Nov. 21, 2010.

Image taken by Don DeBold, Dec. 28, 2013.

The speed at which things change fundamentally, both within information technology and higher education, makes it clear that traditional approaches will not take us where we need to go. We need to develop organizations that are more networked and interconnected, that are flatter, flexible, and focused on outcomes. We need to develop learning organizations that can respond to both challenge and opportunity without managers playing the role of parent.

A great deal of evidence collected over several decades and significant research have identified the qualities and characteristics of effective leadership. As technologists, do we pay enough attention to the science of organizational development? Effective leadership is the key to solving the challenges and opportunities before us. No longer are the principles of emotional intelligence and organizational effectiveness reserved for senior leaders. These skills and competencies must become part of the core requirements for anyone in a leadership position. As an industry, we need to find ways to offer professional development for the most critical aspect of a manager's tool kit — leading people.

- 2014 Study of the Higher Education Chief Information Officer Roles and Effectiveness, Center for Higher Education, Chief Information Officers Studies (CHECS), 2014, 53.

- Michael Maccoby, "Why People Follow the Leader: The Power of Transference," Harvard Business Review, September 2004.

- Chris Argyris, "Double-Loop Learning in Organizations," Harvard Business Review, September 1977.

- John P. Kotter, Leading Change (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1996).

- Hay Group, "Emotional and Social Competency Inventory," 2008.

- Michael Watkins, "How Managers Become Leaders: The Seven Seismic Shifts of Perspective and Responsibility," Harvard Business Review, June 2012.

- Argyris, "Double-Loop Learning in Organizations."

© 2014 Michael Kubit. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 license.