Key Takeaways

- Based on the theory of connectivism, MOOCs originally sought to leverage the Internet as a collaborative communications platform to facilitate connections among learners and dissolve traditional ideas of "knowledge giver" and "knowledge receiver."

- Today's MOOCs have drifted far from this vision and typically treat the communications platform as simply a new tool for delivering the same old content rather than as inseparable from pedagogy itself.

- The University of Pennsylvania's ModPo MOOC takes a hybrid approach, adopting contemporary MOOC structures — such as a detailed course syllabus and discussion forums — while also taking advantage of the platform's ability to create a massive global community of interacting learners and incorporating this dynamic into the pedagogical approach.

David Poplar is a former attorney and a graduate student in the College of Liberal and Professional Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

Like a conspicuous cell tower erected in a residential suburb, massive open online classes (MOOCs) — and discussions about them — have become a part of our educational landscape. The MOOCs we see today often bear little resemblance to the original MOOCs, which were based on a fairly radical learning theory called connectivism. Generally speaking, connectivism posits that, because knowledge is now accessible virtually anywhere, learning has become the interactive process of forming connections between information sources. Early connectivist MOOCs were thus designed to leverage the Internet as a massive and collaborative communications platform to facilitate these connections. As MOOCs evolved — along with large platforms such as Coursera, edX, and Udacity — they have actually grown apart from their connectivist ancestors and adopted a more traditional pedagogical approach, using the technology as more of a delivery mechanism than as an inseparable part of the pedagogy itself. As a result, many of today's MOOCs are less collaborative and less interactive than earlier ones; for many educators and students, this shift represents a step backwards.

One attempt to reincorporate connectivist principles into a MOOC can be seen in the University of Pennsylvania‘s Modern American Poetry ("ModPo") MOOC taught by Professor Al Filreis through Coursera. ModPo has developed several ways to take advantage of the most unique aspect of the communications platform — the ability to create a massive global community of learners who can interact with each other — and incorporates these into the pedagogical approach.

What follows is a discussion of how ModPo does this, based on my experiences as a teaching assistant for the course since its inception in 2012. I begin by briefly describing connectivism and how it drove the original MOOCs (now known as cMOOCs). I then discuss the distinctly different MOOCs that emerged — xMOOCs — and how they reverted to a more traditional pedagogical approach. Finally, I describe ModPo's hybrid approach, and three specific ways that it attempts to bridge these two breeds of MOOC.

Origin of the Species: Connectivism

To understand MOOCs as they presently exist, it is necessary to discuss briefly the innovative — and controversial — proposed learning theory that inspired them. Connectivism explains both how and why the first MOOCs were uniquely designed to incorporate technology, not just as a tool, but as an inextricable part of the learning process itself. This discussion shows, by contrast, how different today's MOOCs are and how differently they employ technology.

Connectivism: In Theory

Connectivism was first discussed in George Siemens' 2004 article, "Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age."1 Siemens offered connectivism as a successor learning theory to behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism, and one that explicitly recognizes how our way of learning has been dramatically influenced — and even shaped — by the technological world in which we live.2 This new theory was needed because the earlier theories are, according to Siemens, limited and incomplete in that they fail to address the "learning that occurs outside of people (i.e., learning that is stored and manipulated by technology). They also fail to describe how learning happens within organizations."3 Just as importantly, the theory of connectivism considers the nature of the information itself, and how our informational landscape today is a virtual chaos of data, which itself is constantly changing and evolving.4

Connectivism makes two primary observations about how we learn within this new environment. First, it asserts that knowledge is not something that resides solely in an individual, but exists throughout a distributed network of various resources — from databases and other "non-human appliances" to other people and social groups. Second, the learning process is the process of forming connections between those many different resources.5 Thus, the information landscape can be seen as a system of pipes that serve to connect various "nodes" (which can be almost anything — "fields, ideas, communities" — that we instinctively view as "knowledge"). These nodes form networks of pipes, and the focus is on the system of pipes, not the nodes. Simply stated, "The pipe is more important than the content within the pipe."6

This conceptual framework is quite different from that of traditional learning systems, and one that is controversial from the standpoint of institutional higher education. Connectivism directly undercuts the dynamic of knowledge giver and knowledge receiver (and, by extension, the dynamic of the university as institutional knowledge provider and the student as knowledge consumer). Moreover, regardless of whether the knowledge provider is the university (as knowledge repository) or the professor (as knowledge conveyor), connectivism deconstructs and dissolves the traditional teacher–student relationship: Students are no longer the passive recipients of knowledge, but actively participate in developing their own knowledge and that of everyone with whom they are connected. Consequently, in a strict connectivist approach, the teacher's role is transformed into that of a facilitator, but theoretically, it could be absent altogether.7 It is students who drive the direction of the class; as a collective, they determine what gets taught, and then learn from each other.

Criticisms of Connectivism as a Learning Theory

Connectivism has not been universally recognized. Significant controversy exists over whether connectivism replaces or merely supplements existing learning theories, whether it is simply repackaged from existing theories, and whether it is even capable of comprising a learning theory at all.8 Critics have argued that while connectivism claims to recognize a paradigm shift in our learning environment and information landscape, it does not actually add anything to the principles of existing theories. One early critique characterized it as simply a "pedagogical view on education,"9 rather than a description of a new way of learning, and maintained that connectivism's emphasis on building connections is merely the basic philosophy that students should form connections to enhance their ability to network and manage information.10

Another hurdle connectivism faces in being considered a learning theory could be the way in which it defines knowledge. For example, Stephen Downes, another highly regarded architect of connectivism, denies that knowledge is propositional, and instead views it in a strictly non-cognitivist sense — that is, knowledge is "literally the set of connections formed by actions and experience."11 Accordingly, to "know" something is simply to have a set of neural connections — to be in a certain unique physical state. Acquiring knowledge or learning is therefore the process of forming these connections and physical states.12 It might be that shedding traditional concepts of representational meaning (concepts we often take for granted) and replacing them with more amorphous conceptions of meaning is precisely why many find it difficult to describe connectivism within the confines of a more normative learning theory.13 Many of these theories and criticisms become much clearer when looking at how connectivist MOOCs actually operate.

Connectivism in Practice: The First MOOCs

The first attempt to put this theory into practice — that is, the first attempt to teach a MOOC14 — was made in 2008 by George Siemens and Stephen Downes. Their MOOC was, in a meta-twist, called Connectivism and Connected Knowledge. Referred to as CCK08, the course was offered formally at the University of Manitoba as well as online for free, succeeding a number of successful OOCs.15 This presented the interesting experience of using connectivism to learn about connectivism.16 As Downes described it, the course "is not simply about the use of networks of diverse technologies; it is a network of diverse technologies."17

The curricula of CCK08 and other early MOOCs typically consisted of a daily e-mail that aggregated links to various sources related to the course, which were constantly updated and supplemented through the students' influence and participation. This was loosely driven by a syllabus that listed the themes and initial readings for each week's discussion, along with the course wiki. Students created their own blogs to share with classmates, and then discussed the material with their classmates online through Moodle or other forums, such as online chat platforms or Second Life. Through this process, students sifted through a chaos of data, absorbed what they felt was relevant, recombined and refined it with other information that they had amassed from their networks, and shared the data with others. In short, they formed a community of learners, all of whom worked together.

Needless to say, these original MOOCs were significantly different from traditional university courses — and even from traditional distance education. It was not merely the endeavor's scale that was unique (through its OpenCourseWare initiative, MIT had been making its educational materials free to the world since 2002), but it was also the way in which these first MOOCs leveraged the communications technology to connect and empower everyone involved, as both learners and teachers. Consequently, the courses did in practice what connectivism did in theory: They undercut the long-established dynamic of the teacher as knowledge giver and the student as knowledge receiver — and, by extension, the dynamic of the university as institutional knowledge provider and the student as knowledge consumer.

Divergent Evolution: xMOOCs

As the promise of MOOCs grew — and perhaps most enticingly, as MOOCs leveraged the Internet to promote massive scalability — institutionalized higher education wanted in. However, the pure connectivist MOOCs were, and still are, considered extreme by the academic establishment. This is why we have seen the development of a different and distinct MOOC species in the past few years — a MOOC that often bears remarkably little resemblance to its progenitor and draws little from the underlying connectivist principles.

Development of xMOOCs

This newer breed of institutional MOOC has been labeled "xMOOCs," to distinguish it from the original, overtly connectivist-driven MOOCs such as CCK08, which have been dubbed "cMOOCs."18 xMOOCs are usually associated with major universities and offer courses created and taught by well-known instructors, and include those produced by large platforms like Coursera, edX, and Udacity.

Unlike cMOOCs, whose curriculum is significantly directed by the students as a collective, xMOOCs operate much more like traditional university courses. Generally speaking, content is standardized, with fixed syllabi created by professors who also select the course content and how it is taught, and these components are not subject to change. The content typically consists of video-recorded lectures by the professor, which are similar to those given in the classroom except that they are trimmed into multiple shorter segments. The courses also include online forums for students to discuss the course, but they operate with little or no instructor involvement and have little or no impact upon the course's direction (other than sometimes generating a short list of questions for the professor to answer via e-mail or a brief video). Quizzes and examinations are given and graded automatically; although a peer-review process is sometimes used, this also typically occurs with little or no professor involvement.

These xMOOCs19 thus represent a one-way flow of information that preserves the dynamic of the professor as institutional knowledge provider and the student as knowledge consumer. The pedagogy remains the same, and the courses take advantage of the MOOC concept more as a scalable delivery system than as a platform for interactive communication and collaboration.

Moving Beyond xMOOCs

Without question, xMOOCs are seen by many MOOC purists as something of a step backward. Separate from criticisms about their potential disruption and purported ineffectiveness, xMOOCs may represent a lost opportunity for pedagogical innovation. This is because, in many ways, xMOOCs have tried to take advantage of communications technology, but have made little attempt to consider how it can be more effectively implemented into the pedagogy.

Even more troubling, in response to this radically different teaching environment, some instructors have migrated farther away from the students. Instructors provide their standard content, but assume that they would be unable to have any meaningful interaction with such a massive amount of students. And, as a result, many don't. Their xMOOCs become little more than static multimedia textbooks for self-study; the only thing the new platform adds to these classes is the possibility for students to have unsupervised and unguided discussions with others. In this atmosphere, students are not classmates as much as they are users taking the same class, and this is more than a semantic distinction.

These problems might be the result of xMOOCs' attempt to force the square peg of traditional pedagogy into the round hole of a new communications platform, where educators try to adapt their preexisting educational content and approach to the new technology. cMOOCs, however, take a much different approach: They do not start with a defined body of information, but rather with the platform itself. They then let the platform drive the pedagogy — and even determine much of the content. xMOOCs are structured the way they are for many practical reasons, and it might not be feasible or even desirable to reshape every xMOOC into something more closely resembling a cMOOC. Nonetheless, xMOOCs need not remain a distinct and isolated species, because there are aspects of cMOOCs that can be used to enhance the xMOOC experience. ModPo was designed specifically with this in mind.20

Selection and Adaptation: The ModPo Experience

ModPo was first offered in the fall of 2012, and was the first MOOC on a humanities subject offered by Coursera — and one of (if not the) first humanities MOOC in the short but dense history of MOOCs in general. In some basic and perhaps inevitable ways, ModPo uses the xMOOC platform's general structure. It has a course syllabus that lists topics for each of the 10 weeks of study and gives links to the course materials, which consist of poems and related teacher-created video "content." It also uses online discussion forums for students to discuss these materials. Although grades are not given for the course, students must take quizzes, complete writing assignments, peer-review each other's writing assignments, and post to the discussion forums to earn a certificate of completion. In other ways, however, ModPo adamantly resists the xMOOC dynamic and the more traditional pedagogical approach it encourages. What follows are three of the ways that ModPo seeks to rethink and retool the platform's relationship to teaching: Through leveraging collective knowledge, by creating a community through a sense of place, and by maintaining an interactive presence between instructors and students.

Figure 1. The ModPo home page

Leveraging Collective Knowledge

If xMOOCs share anything with their connectivist ancestors, it is the way that they allow massive numbers of students to take part in the same educational experience. The experience is not just a one-way relationship between the student and the course material; the MOOC technological platform provides the unique ability for a student to interact with an entire community of learners. This is more than just an advantage for the students who share in the experience; it's also an advantage for instructors, who can use the community to enhance the course.21

For ModPo, fostering the learning community began months before the course officially started, through e-mail updates sent to registered students and through a ModPo Twitter account, which the professor used to publicize the course and communicate (briefly) with interested students. In addition, a student created a ModPo Facebook group that was publicized in the e-mail updates. The group grew quickly and reached 1,000 members a week before the course officially started on September 10, 2012. Thus, by the time the course actually started, the group was well established, and relationships among students from all over the world had already begun to form. To this day, the professor and teaching assistants periodically join in conversation threads with this group (which has remained active continuously, not just during the course sessions), but it has always been made clear that participation in the Facebook group was voluntary, and that it was created and owned by the community. The ultimate goal was for the group to be related to (but independent of) the course and to grow organically on its own (figure 2). This has been the case — the group remains very active and had 6,702 members as of October 1, 2014.

Figure 2. The ModPo Facebook Group page showing (L-R) Amaris Cuchanski, Max McKenna, Professor Al Filreis, Kristen Martin, and David Poplar

When planning the course, the professor hoped for anywhere from 10,000 to 15,000 students, but it soon became evident that such estimates were low. A week before the class began, there were 28,031 students enrolled; by September 9, 2012 — the day before the course began — that figure was up to 30,090 .22 Students could continue registering even after the course began, and by the end of the first session, enrollment had reached 36,523.23 The second session of ModPo started on September 8, 2013 and had similar enrollment statistics: by the end of that second session, there were a total of 37,102 registered students. The social media likely contributed to the increasing number of registrants in the last weeks leading up to the course, as well as playing a role in establishing the community.

In terms of the course's operation, ModPo overtly stresses that its approach to learning is collaborative, and the video content reflects this: Unlike most xMOOCs, ModPo videos do not consist of lectures by the professor, but of collaborative close readings of individual poems — that is, of unscripted round table discussions between the professor and several teaching assistants.24 Also, rather than a fixed camera, a handheld camera was used to follow the discussion from person to person, creating a more intimate environment (figure 3). The same teaching assistants appeared in each video, allowing students to become familiar with each individual (figure 4). This familiarity was reinforced as the TAs participated with students in the discussion forums and held regularly scheduled "office hours," which operated like chat sessions within the forums. As such, the videos try to emulate the "feel" of being part of a discussion seminar. They are also designed to serve a much more important purpose: They are not presented as the definitive interpretations or meanings of the poems, but as models for the students to use on their own to discover their own interpretations or meanings.

Figure 3. Filming of ModPo Professor Al Filreis and his teaching assistants (L-R: Penn Video Network Videographer Kari Ries, Emily Harnett, Amaris Cuchanski, David Poplar, Ali Castleman, Professor Al Filreis, Anna Strong (hidden), Molly O'Neill, and Max McKenna)

Figure 4. Recording video of Professor Filreis and his teaching assistants (L-R: Penn Video Network Director Gates Rhodes, Emily Harnett, Amaris Cuchanski, David Poplar, Ali Castleman (blocked), Professor Al Filreis (blocked), Anna Strong (blocked), Molly O'Neill (blocked), and Max McKenna)

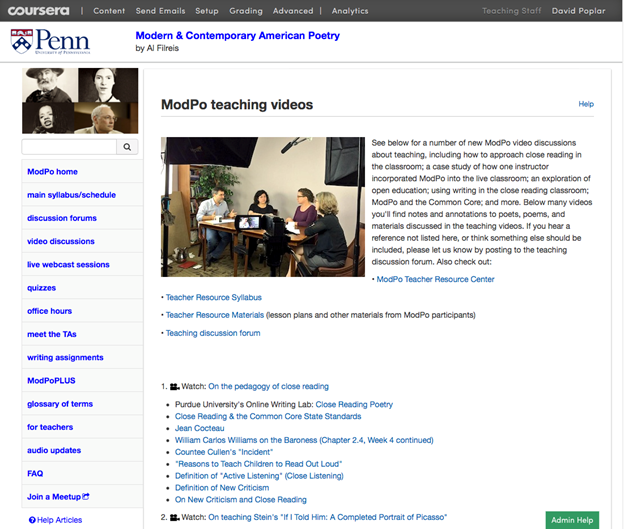

The first and second sessions of ModPo had 82 of these video discussions, each of which were approximately 20 minutes in length and discussed a single poem. The professor and the same group of TAs reassembled recently to record 30 new video discussions for ModPo's third session, which began on September 6, 2014. These are part of the course's new "ModPoPlus" section, which are not part of the course requirements, but are offered for students who either have already taken the course or who wish to explore more poetry within ModPo's group dynamic. Also recently added was the ModPo Teacher Resource Center,25 an area for teachers at all levels to discuss poetry and pedagogy (figure 5). This further serves as a storehouse for resources about teaching poetry online and in person, with suggested approaches on how to incorporate ModPo into a classroom setting. The goal has been to continually enhance the original content and offer new material to ensure that each session of the course offers a different experience. This also gives former students incentive to take the course again, and results in more students in the community who are able to help new students with the content or navigating the platform.

Figure 5. The ModPo Teacher Resource Center's video discussions page (L-R: professors Al Filreis, Erica Kaufman, Kristen Gallagher, and Julia Bloch)

Encouraging collaboration is nothing new, but the platform makes collaboration possible in many new ways, with many more people from all over the world. The primary area for this in ModPo (and xMOOCs generally) is the online discussion forums, where the professor and TAs maintain an active presence to foster interactivity (as discussed in more detail below). This active presence also encourages students to develop their own interpretations through collaboration with both students and the course instructors.

Students are also encouraged to form in-person discussion groups on their own or through meetup.com [http://www.meetup.com/Coursera], and to discuss the material in other online mediums of their choice. As with the Facebook group, the idea is to let this to be a student effort rather than a course-coordinated one, to further promote the course's group discussion models over a single regimented approach. The students' many different perspectives, ideas, and interpretations are then discussed in the ModPo forums, adding to the collective knowledge of the student body and the overall sense of community. As an illustration of this global collaboration using the ModPo discussions as a model, a group of three students from Edinburgh video-recorded their own close reading of a Tom Leonard poem, which they shared with their fellow students.

ModPo students in Edinburgh

The community is given center stage in live webcasts, which are hosted weekly at various times to accommodate the global student body. During these sessions, the professor and TAs engage in conversations with students who are present in the room or who call over the telephone, and questions are taken from students via e-mail, Facebook, and Twitter. The professor also comments on specific posts and discussions taking place in the forums. Often, posts are chosen because of their innovative interpretations or because they show the value of collaborative interpretations, but just as often, the professor discusses posts in which students offer personal accounts of how the exposure to poetry and the supportive community have impacted them personally.

Live webcasts are often used by professors to respond to student questions, but the emphasis of ModPo webcasts is different: they are not just informational, but rather are intended to counter the traditional xMOOC dynamic of a one-way flow of information from teacher to student, and thereby to become one component of a much larger interactive educational experience. This experience is fueled not by information imparted by the professor, but comes from the community, through everyone contributing and learning together. Students are not merely learners; they are also contributors and teachers, and are recognized as such.

Creating a Community through a Sense of Place

It is important to recognize how practically and physically different the online class experience is from a traditional in-person course. Typically, MOOC students participate using their own computer located in their familiar environment. The instructor, the course material, and all of their classmates exist somewhere on the other end of their monitors, somewhere out in the ether. Combined with students' ability to control when to access content or participate in online conversations (including when, or if, to respond to questions directed at them), the entire experience reinforces a student's separation from the collective. It does not simply remove the learning experience from a physical location and physical interaction; in many ways, it removes it from a sense of present reality.

When an actual physical place or location is introduced, the overall experience is no longer as abstract. Having a physical location associated with the course — even something as basic as using the same identifiable classroom as a backdrop for the video-recorded content — gives a more concrete sense of place that becomes familiar for students. Virtually speaking, students can be in that classroom at the other end of the monitor, rather than just monitoring it.

This notion finds support in spatial theory, which makes similar observations about the importance of community, with emphasis on the actual physical space in which learning takes place. A "community of learners" can be more than a conceptual description of students, but an entity in and of itself. This idea of community cannot be divorced from how people learn, because all communities have unique aspects that impact the perspectives of people within them and even how they process information.26 This becomes especially significant in a MOOC, which often brings together people from all over the world.

ModPo was uniquely positioned to create a sense of community because it grew out of the Kelly Writers House, a real and long-established community (figure 6). All ModPo videos and webcasts are recorded at the Writers House, an 1851 Victorian cottage on the University of Pennsylvania campus that has served as the center for creative writing at Penn and the surrounding Philadelphia community since 1995. Every year, the Writers House hosts approximately 300 writing-related events, as well as hosting classes and meetings of community groups and serving as the "home" of ModPo.27

Figure 6. Opening of discussion video showing entrance to the Kelly Writers House

Like every event at the Writers House, the live webcasts are free and open to the public, and ModPo students are encouraged to attend in person. Many have, including some who travelled to Philadelphia from New York City and Washington, D.C., and others who traveled from even farther away, including one student who came from Melbourne, Australia, to attend the final webcast of the 2013 course. In all ModPo webcasts, students who are present are brought into the discussions, which not only enhances the course experience for them, but shows the majority of students who "attend" only remotely that the course is as real as an in-person class in a brick-and-mortar setting, not a pre-recorded, static multimedia textbook.

It might seem that mooring an xMOOC in physical reality is the antithesis of a connectivist approach, which views the world as a series of connections that transcend any notion of physical space. However, the physicality of the Kelly Writers House space is used not to assert that a physical institution is the warehouse of knowledge, but rather to promote connections among people. It thus serves to foster and encourage a connectivist approach and help students form more connections, leading to even further connections, and so on. In connectivist terms, the location is just another node (albeit a much larger one) that acts like a router in the overall web of connections.

Maintaining an Interactive Presence

With tens of thousands of students, interacting with each student in the same way as in a traditional university setting is impossible. As a result, some instructors might think that any type of interaction with students is also impossible and assume that this is just a reality of the MOOC platform. Presumably, this is why some xMOOCs instructors do not participate in discussion forums, and some merely assign an assistant to monitor the discussions. Needless to say, this does not foster a sense of connection between the students and the instructor, but rather reinforces a feeling of distance and even isolation. (Indeed, many consider the biggest drawback of MOOCs to be the loss of the interactive exchange that occurs in the classroom environment.) If the instructor ignores students, the instructor is reduced to a face in a video and the course feels like a completely prepackaged course on-demand.

From the beginning, ModPo sought to counter that dynamic and break down the virtual wall separating students from teacher. Primarily, this is accomplished by the professor and TAs maintaining an active presence in the discussion forums, and, to a lesser extent, in other student-created forums such as the Facebook group. Needless to say, this is no small task. In the first session of ModPo, the forums saw a total of 148,587 threads, posts, and comments from 5,842 students, which generated a total of 957,443 views. However, the primary emphasis for the instructors is on quantity of interactions — the goals are to answer questions, comment on as many discussions as possible, and show students that the teachers are listening. For ModPo's second session, some of the students who had been especially active contributors in the first session were invited to become "Community TAs" to further assist in this effort. Thus, in the second session, despite the number of students, it was a rare discussion thread that did not bear at least one comment from the professor, a TA, or a Community TA.

The live webcasts are another way the course maintains an interactive dynamic (figure 7). (The webcasts are also archived and available on the ModPoPenn YouTube channel.) In addition, the professor records semi-weekly audio updates and uploads them to the syllabus; in them, he discusses many of the different conversation threads from the past week and addresses specific ideas or concerns raised in the forums. Furthermore, on several occasions, some of the contemporary poets studied in the course have actually joined in the online discussions about their work. Thus, in some ways, this xMOOC was able to provide more interaction than a typical in-person class.

Figure 7. Live webcast from the Kelly Writers House (L-R: Molly O'Neill, Emily Harnett, Ali Castleman, Professor Al Filreis, David Poplar, Anna Strong, and Max McKenna; lead TA Julia Block at bottom)

Conclusion

cMOOCs and their underlying theory of connectivism do more than just blur the distinction between communications technology and educational content, they deny the distinction altogether. The platform cannot be separated from the content; as a result, the direction of cMOOCs is dictated fluidly by the collective. This holistic approach is radical and is impractical for many kinds of courses. However, xMOOCs have largely considered the communications platform as entirely separate from the educational content and underlying pedagogy, using it only as a new tool for delivering the same content. This might well be a mistake, because this technology presents truly unprecedented opportunities for global and interactive communications experiences — and, consequently, opportunities for pedagogical innovation.

ModPo might be a hybridized version of xMOOCs and cMOOCs, or perhaps it is an xMOOC with a cMOOC bent. Regardless of where it fits on the spectrum, it represents an attempt to rethink the relationship between technology and pedagogy, and hopefully contributes to the larger conversation about new ways to fully leverage this new environment.

- George Siemens, "Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age" [http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm], eLearnspace, 2013.

- Ibid.; and Frances Bell, "Connectivism: Its Place in Theory-Informed Research and Innovation in Technology-Enabled Learning," International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 12, no. 3 (2011): 102.

- Siemens, "Connectivism: A Learning Theory" [http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm].

- Although 2004 may not seem so long ago, in terms of technology's social impact, it was. To put it in context, at that time YouTube did not yet exist, Facebook was limited to college students, and the first iPhone was still two years away.

- Siemens, "Connectivism: A Learning Theory" [http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm].

- Siemens, "Connectivism: A Learning Theory" [http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm]. A great resource for gaining a deeper understanding of Siemens' views on connectivism, along with those of Stephen Downes (who, like Siemens, is an educational theorist and professor and has been a truly prolific advocate for connectivism since 2005) can be found in a 2007 online discussion forum in which they explain their ideas and respond to complex questions from other experienced educators and educational theorists. The discussion took place on Moodle and is no longer available except through Archive.org.

- Rita Kop, "The Challenges to Connectivist Learning on Open Online Networks: Learning Experiences during a Massive Open Online Course," International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 12, no. 3 (2011): 19.

- Frances Bell, "Connectivism: Its Place in Theory-Informed Research," 103; and Rita Kop and Adrian Hill, "Connectivism: Learning Theory of the Future Or Vestige of the Past?" International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 9, no. 3 (2008). Of course, As Frances Bell notes, what constitutes a "learning theory" is also a bit murky, and "begs the question of whether we conceive of learning as a process or a product." ("Connectivism: Its Place," 101).

- Bell, "Connectivism: Its Place in Theory-Informed Research," 103; and Pløn W. Verhagen, "Connectivism: A New Learning Theory?" November 11, 2006.

- Ibid.

- Stephen Downes, "What Connectivism Is," blog, Half an Hour, last modified February 3, 2007.

- Ibid.

- Another broader criticism of connectivism and its use in MOOCs is that this hyper-collaborative approach to learning stifles important aspects of individuality (see Carmen Tschofen and Jenny Mackness, "Connectivism and Dimensions of Individual Experience," International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, vol. 13, no. 1, 2012). Among the chaos of mass information and networks, the concern is that individual perspectives will be discounted, thus resituating learning more within the "combinatorial creativity" idea while devaluing the "lone genius" concept (Ibid., 125). In detailing this critique, Tschofen and Mackness offer an excellent discussion of connectivism in relation to personality theory and self-determination theory. Their conclusion is not necessarily critical of MOOCs, but suggests instructors should be mindful of these competing concepts about individualism. Ultimately, the authors contend that connectivism must consider individuals, otherwise it is not a learning theory but merely a description of the flow of information (Ibid., 138).

- It apparently took two — or possibly three — people to devise the acroynym MOOC. The credit (or blame) is typically given to Dave Cormier, then the Web projects lead at the University of Prince Edward Island; and Bryan Alexander, then the director of research for the National Institute for Technology in Liberal Education (see Chris Parr, "MOOC Creators Criticise Courses' Lack of Creativity," The Times Higher Education, October 17, 2013; and Russell L. Herman, "Letter from the Editor-in-Chief: The MOOCs are Coming," The Journal of Effective Teaching 12, no. 2, 2012). Cormier and Alexander were collaborating on what would become the first course to embody the connectivist approach and trying to figure out what to call it. Cormier also suggested that the term might have emerged from a Skype chat he had with George Siemens while preparing for the course (see Dave Cormier's 2008 blog post, "The CCK08 MOOC–Connectivism Course, ¼ Way").

- Stephen Downes, "Places to Go: Connectivism and Connective Knowledge,"Innovate, vol. 4, no. 4 (April 1, 2088); and C. Osvaldo Rodriguez, "MOOCs and the AI-Stanford Like Courses: Two Successful and Distinct Course Formats for Massive Open Online Courses," European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning, July 5, 2012.

- Paul Stacey, "The Pedagogy of MOOCs" [http://mooc.efquel.org/week-9-the-pedagogy-of-moocs-by-paul-stacey]. European Foundation for Quality in e-Learning, July 17, 2013.

- Downes, "Places to Go."

- The etymology of these labels can to be traced to Stephen Downes. In a blog post, he explained that he began referring to the university-driven MOOCs as xMOOCs to differentiate them from programs "that aren't part of the core offering, but which are in some way extensions," such as in "TEDx" talks (see Stephen Downes, "What the ‘x' in ‘xMOOC' stands for," Google+ post, April 9, 2013. Downes also took the "x" from other U.S. MOOCs, such as EdX, and only later began calling the connectivist MOOCs "cMOOCs" (Ibid).

- This xMOOCs description is an extreme oversimplification. Many innovative xMOOCs incorporate aspects of connectivism and other pedagogical approaches that are specifically geared to work within the unique MOOC format and leverage its ability to facilitate collaboration among numerous students. Still, the above description of the typical xMOOC is not unsupported. In fact, this version, characterized by the instructor's non-interactivity with students and reliance upon fixed course content is the easiest model to scale. Consequently, such a MOOC is also the most cost-effective and potentially profitable, because it could be deployed anytime and anywhere, even without the professor and without supervision.

- Professor Al Filreis was in many ways uniquely situated to create and design ModPo. In addition to having taught an in-person version of this course for decades, Filreis has been teaching poetry and literature online in various forms since the early 1990s.

- This collaborative experience can be of great use to instructors in their own work as well. As Princeton University Professor Mitchell Duneier said about his experience teaching his popular sociology MOOC, "Within three weeks I had received more feedback on my sociological ideas than I had in a career of teaching, which significantly influenced each of my subsequent lectures and seminars." (Mitchell Duneier, "Teaching to the World from Central New Jersey," The Chronic of Higher Education, September 3, 2012).

- This group included Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois (see Daniel Luzer, ‘‘Dick Durbin Tries Online Poetry Class," Washington Monthly: College Guide, September 21, 2012).

- The course website on Coursera remained accessible to registered students even after the first session's course was complete, and the discussion forums remained open. The number of registrants has continued to rise; as of August 5, 2014 there were 45,461 registered students. The course's introductory video is available on YouTube. An overview of the first two sessions of ModPo, including links to reviews and articles about the course, can be found on Jacket2, a website dedicated to modern and contemporary poetry and poetics.

- As the Harvard and MIT researchers pointed out in their study of edX xMOOCs, however, statistics about xMOOCs should not be compared with other types of courses, but must be understood in their unique context (see Andrew Dean Ho and colleagues, "HarvardX and MITx: The First Year of Open Online Courses," HarvardX and MITx working paper no. 1, January 21, 2014). This may be especially true with enrollment figures, because many students register for these free classes, but do not engage with the course at all; these figures should be distinguished from statistics reflecting students who make initial efforts and then later drop a course, which at some level could reflect students' judgment about the course's quality or nature. This also raises the question whether completion statistics should consider students who register but do not participate or even access the course website, or only students who make some sort of affirmative effort. In ModPo's first session, for example, among the 30,000 registered students, 17,754 unique users viewed the video discussions, which were largely considered to be the foundation of the course. A total of 1,121 students received certificates of completion in that first session.

- This section is curated by Julia Bloch, the lead TA for ModPo and associate director of the Kelly Writers House; and Erica Kaufman, associate director of the Institute for Writing & Thinking at Bard College.

- This ties into Stanley Fish's theory of "interpretive community" as well as Randy Garrison and Terry Anderson's theories of "communities of inquiry" and "communities of practice," – all of which (broadly speaking) recognize how our social and cultural environment shapes the way we learn (see Louise Marshall and Will Slocombe, "From Passive to Active Voices: Technology, Community, and Literary Studies," in Teaching Literature at a Distance: Open, Online and Blended Learning, Takis Kayalis and Anastasia Natsina ed., Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010, 105–106).

- For many people, this sense of place, and having a connection to it as the symbol of the community, was an extremely important aspect of the course and their overall experience. As an example, during the video discussions, the professor and TAs drank from coffee mugs bearing the Kelly Writers House name; it was not long before students were asking how they could get their own KWH mugs. Students then shared photographs of themselves with their mugs, adding to the overall sense of community, and also reinforcing the fact that it was a community comprised of actual people, not just faceless computer users.

© 2014 David Poplar. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.