Key Takeaways

- The Air Force Culture and Language Center offers two innovative, online, self-paced culture education courses that use military-centric and student-generated scenarios to illustrate main concepts and focus on cross-cultural skills relevant to military personnel.

- The flexibility and accessibility afforded by self-pacing and the use of real-life frameworks and scenarios have proven key to student success and retention.

- Successful design elements for the courses that can be applied to other online courses include using an introductory video, systematic assessments, and student feedback and participation, mostly notably through a wiki.

Since 2009, the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) has led U.S. military efforts to provide culture education for college credit via two innovative, online, self-paced courses. Introduction to Culture and Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication are distinct from courses offered at civilian universities in several ways: they use military-centric and student-generated scenarios to illustrate main concepts; they focus on cross-cultural skills relevant to military personnel; and their self-paced format is designed to accommodate military students' atypical and often unpredictable schedules.1 In addition, the courses set themselves apart from other Department of Defense (DoD) culture training in that they are semester-long, 3-credit college courses that take a general approach to culture education as opposed to a culture-specific approach. More than 3,000 students have completed the classes since 2009, and retention rates per semester typically hover at or above the national average for civilian online courses.2

Close and careful study of online courses such as these is important because, despite the vast number of deployments and temporary duty assignments all over the world, the number of military members seeking higher education continues to rise.3 Research devoted to students in the military indicates that flexibility and accessibility to support services are necessary to most effectively serve the military population.4 As such, the AFCLC distance education classes are designed to ensure that, regardless of where they are located — on base or at home in the United States, deployed to Afghanistan, or stationed in Korea, for example — thousands of students can access the courses at the time and place of their choosing.

This article outlines the course content, key findings, and best practices associated with these two AFCLC online culture courses. Sharing best practices has been cited by numerous scholars as an important strategy for knowledge transfer both within and across organizations.5 In an effort to contribute to the scholarship on best practices in distance learning and military culture education, we argue that the design and assessment processes adopted by the AFCLC can serve as a model for teaching culture online throughout the DoD.6

Why Culture? Contextualizing the Course Content

The Air Force mission is no longer restricted to air and space operations. The scope of our military is so wide that Air Force personnel might find themselves conducting a humanitarian aid drop in conjunction with the International Red Cross, treating patients at a medical clinic in Haiti, or building a new runway using local contractors at a forward operating base, among other things. The evolving nature of military operations has made cultural awareness and the ability to interact in a cross-culturally competent manner an important factor for mission success. The level of cultural knowledge needed to succeed in such efforts is captured in a speech delivered by President Obama: "In the 21st century, military strength will be measured not only by the weapons our troops carry, but by the languages they speak and the cultures they understand."7

The ability of service members to perform their job often hinges on understanding the potential effects of cross-cultural interaction.8 Education and training devoted to improving competence in dealing with cultural difference, thereby minimizing misunderstanding and conflict in culturally complex environments, is a necessary skill for military personnel in the diverse professional environment of the 21st century.9

Responding to this need for military culture education has been a priority for the AFCLC since its inception. Among its many missions, the center is charged with integrating cultural awareness into all levels of Air Force education and with familiarizing students with the skills and concepts necessary to develop cross-cultural competence.10 The two AFCLC courses featured in this article are offered via the Community College of the Air Force (CCAF), the "largest multi-campus community college in the world and the only community college in the Department of Defense."11 It is worth noting that everyone who enlists in the Air Force is automatically enrolled in CCAF to work toward their associate's degree, which is a reflection of the high value the Air Force places on higher education. Traditionally, CCAF has awarded academic credit for technical training provided through the Air Force; students combine that credit with general education courses taken at affiliated colleges to complete their applied science degrees. The two AFCLC offerings are the first general-education courses developed by the Air Force and offered to CCAF students.

First developed by the AFCLC in 2009, Introduction to Culture is now in its ninth semester offering. Soon to enter its seventh semester, the Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication course was piloted in 2011. These two currently offered 3-credit, lower-division, undergraduate-level courses have no prerequisites and complement each other. They are fundamental components of the effort to transform culture education in the Air Force, which is the primary goal of the Quality Enhancement Plan adopted by Air University in 2009.12

Introduction to Culture Course

Introduction to Culture offers students:

- An overview of general theory about how we learn to interact with the world through culture

- A review of universal cultural characteristics (categories of behavior and belief such as family and kinship, history and myth, economics and resources) and specific examples from a variety of cultures

- An introduction to skills that build their ability to use the theory and categories to improve their cross-cultural competence

As such, Introduction to Culture teaches students how to apply cultural universals to their own lives. Examples from current events and from actual experiences of military personnel in overseas environments supplement the course's academic content. For instance, in one lesson a DoD publication devoted to tribal cultures in Iraq serves as the basis for discussion of social organization. In another lesson, an airman's experience visiting the home of a commander in a foreign country is used to illustrate the meaning of "family" in different cultures. Stories from domestic and international media also illustrate the ways that culture influences our views about the world and our interactions with others.

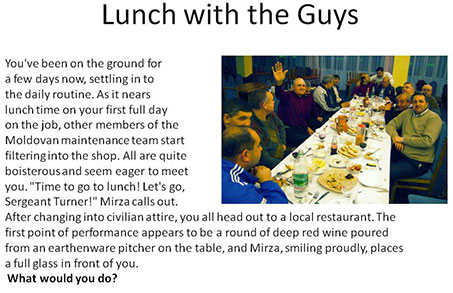

Introduction to Culture also provides the all-enlisted student population with a decision-making feedback loop that previously had only been taught to the Air Force officer corps. The OODA (observe, orient, decide, act) loop is similar to other decision-making tools found in social psychology, but the fact that it was developed by and for Air Force pilots lends the model added legitimacy and links it to Airmen's work environment.13 (Figure 1 illustrates a scenario-based learning opportunity in Introduction to Culture). Through the OODA loop model, students are taught how to minimize bias in their observations and how to orient to the cultural environment by comparing their observations to their existing knowledge. They are encouraged to generate multiple courses of action before making decisions. Finally, the feedback loop instills in students the benefits of acting with culture in mind, and then reviewing their actions for potential errors or successes.

Figure 1. Sample Introduction to Culture scenario-based exercise

In sum, Introduction to Culture focuses on teaching basic cultural knowledge and on applying that knowledge to cross-cultural situations that Air Force students might encounter in their lives, both at work and at home. The focus on skills and application makes Introduction to Culture more similar to a course on cross-cultural awareness than to a traditional anthropology or sociology course offered at most civilian institutions.

Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication Course

An overall goal of Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication is to help students better understand the process of communicating across cultural boundaries — one of the key skills associated with cross-cultural competence. Based on a review of all extant literature on cross-cultural communication competence, both civilian and military, we determined that the course would focus on developing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of students in such areas as:

- Paralinguistic use and perception (i.e., effective and appropriate use of rate of speech, volume, and intonation across cultures)

- Nonverbal communication skills (i.e., effective and appropriate use of touch, space, time, and gesture across cultures)

- Active listening (i.e., identification of culture-specific feedback preferences)

- Identification and adaptation to communication styles (i.e., identification of the communication patterns associated with various cultures)

- Interaction management (i.e., effective and appropriate use of conversational turn-taking)

These communication skills and concepts are just a sampling of those provided by the cross-cultural communication course that help students create a variety of explanations for confusing cross-cultural behavior. The course is filled with examples of successes and failures of cross-cultural communication and their impact on both personal and professional relationships. The skills emphasized throughout this course reinforce the importance of effective and culturally appropriate communication for students.

Course Design for Introduction to Culture and Cross-Cultural Communication

The 45-contact-hour courses are completely self-paced and delivered online via a learning management system (LMS). Readings for both courses are delivered exclusively as e-reserves in PDF format through the LMS, eliminating the need for students to locate or ship text materials — a particularly complex process for deployed students. The courses are 14 weeks in duration to allow students ample time to complete the 12 lessons. Each lesson maintains a consistent design scheme. For example, in Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication, every lesson begins with an introductory video by the professor (see figure 2) lasting approximately five minutes, followed by a film-clip application of the concepts addressed in that lesson, and 20 web pages (on average) of course content per lesson. In a similar fashion, Introduction to Culture lessons on cultural characteristics each begin with an introduction to the universal element and how these cultural characteristics serve to organize behavior, beliefs, and values. In the successive content, the characteristics are explored through concepts and examples that help students make sense of cultural differences throughout the world. In each course, an average of two readings are included and linked into each lesson, along with interactive knowledge checks, scenario-based exercises, and writing exercises to help students relate their own experiences to the course content.

Figure 2. Sample Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication video screenshot

In addition, to help regulate student pacing and maintain test integrity, adaptive release mechanisms are used within the LMS. For example, adaptive release technology prevents students from progressing to a future quiz unless they have taken the previous one. In an attempt to help prepare students for major graded measures (such as the midterm or final exam), a quiz is inserted between each lesson. Quiz results provide formative feedback to students about each multiple-choice option, which not only serves to reinforce course material but also familiarizes students with the types of questions they can expect on exams.

As is the case with most online learning, assessment is an integral part of the design process for both courses. With the assistance of the AFCLC Assessment Directorate, several assessment measures are routinely administered for both courses. The first step is the pre-course survey, which is designed to measure both attitudes and dispositions related to cross-cultural competence and motivation to learn.14 At the beginning of the course, students also take a knowledge pretest (including items randomly drawn from the course quizzes and exams) to gauge the level of their cultural knowledge before being exposed to the course content. Graded measures that also serve assessment purposes include quizzes for each lesson, a midterm exam that tests students on the content from the first half of the course, and a noncumulative final exam that tests students on the content from the second half of the course. In order to collect data on student attitudes and experiences, students receive a post-course survey that re-measures their attitudes and dispositions and collects their reactions to instruction for program evaluation purposes. Lastly, an exit survey administered to students who do not complete the class assesses why they left the course and collects their reactions to the course for program evaluation purposes.

Key Findings

After collecting and analyzing data over the past four years, we came up with the following key findings about the two courses.

Self-Paced Format Improves Completion Rates

The first version of Introduction to Culture ran on a strict schedule, with weekly due dates for discussion board posts and exam due dates spaced throughout the semester. Most students could not keep up with the workload and often turned their work in late. In response to student feedback and a low completion rate, we piloted more flexible formats by eliminating weekly due dates and the requirement of student interaction on the discussion board, but maintained the requirement for interaction with the instructor via essays. When the course was revised for the 2010–11 academic year, the flexibility was further enhanced by making the course completely self-paced. Students' only due date for graded assignments is the last day of the course. The results of this combined effort have been astounding: the completion rates rose from an average of 38 percent in Introduction to Culture's first three semesters to an average of 63 percent in its last three semesters.

This experience reinforced the unique needs of military students in terms of incorporating flexibility in the class schedule. It is important to keep in mind:

- The work of military personnel is not restricted to a typical Monday-to-Friday, 9-to-5 schedule; many do shift work or go on short-notice deployments, subject to the "needs of the Air Force."

- Military personnel routinely take courses while deployed in locations where Internet connections are inconsistent.

- Military personnel who are deployed or on a temporary duty assignment overseas tend to work outside "normal" business hours due to large differences in time zones.

Luckily, the debate between the benefits and limitations of synchronous and asynchronous learning has "left its initial stage," with the understanding that each has its advantages and disadvantages.15 For the purposes of online military culture courses, we maintain that active-duty military students' unique needs are best met via self-paced courses.

Military Frameworks and Scenarios Improve Course Relevance

Along with the need for flexibility, years of course development have taught us that producing a course for the Air Force brings the expectation that course materials will be relevant to students' military job duties. In addition, linking cultural knowledge and practices to everyday life in the military shows students the value of the content beyond the scope of a single course. Thus, along with incorporating flexibility (via the self-paced course) into the course schedule, we have seen success from applying the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other capabilities (KSAO) framework to course content, thereby providing military students with tools to aid their learning and practice after the course ends.

Many studies have identified KSAOs relevant to cross-cultural competence.16 We chose a small subset that the studies suggest can change through instruction and practice — perspective-taking,17 cultural self-awareness,18 and intercultural efficacy19 — and incorporated content and activities to support their development. For example, certain course activities teach students how to be better observers and ways to compare their observations to similar conduct in their own culture. Other parts of Introduction to Culture teach students the benefit of understanding other cultural perspectives through successful and unsuccessful examples of American interactions abroad. In the culminating cross-cultural scenario of the course, students perform well on the questions designed to measure perspective-taking and confidence in cross-cultural interactions, and scenario performance has correlated positively with overall average course grade.20

Of particular relevance in both courses is the use of a situational judgment test, a type of scenario that allows students to apply the concepts they have learned. These applied scenarios assess a student's ability to apply general concepts and methods in novel circumstances, and thus require higher-order thinking and decision making on the part of the student.21 Scenarios for the courses are designed to (1) be consistent with the types of situations students might face on the job or in intercultural interactions while they are stationed abroad, and (2) provide immediate feedback to the student about how optimal each choice is compared to the other options presented. Thus, the testing experience itself is a formative learning tool, allowing students to experience simulated consequences of their cultural choices. (The creation and application of situational judgment tests for military students is the focus of the "Best Practice" section.)

Opportunities for Student Interaction Improves Course Quality

To create a more personalized experience in a self-paced course, we make the following suggestions to future instructors:22

- To connect a name with a face for students in the opening minutes of each lesson, prepare short introductory videos outlining the main points of the lesson and describing how they relate to overall course objectives. This is a great chance for students to see that there is a human element to the operation of the course.

- To create community among students in the course, incorporate a wiki option with discussion prompts where students can describe how they connect to the course content and read about each other's experiences. This helps students stay engaged with the course and can create a "classroom" feeling that is often lacking in self-paced courses.

The idea for including a wiki in Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication was derived from the pilot end-of-course survey, where 18 students requested that an "interactive" item be added to the course. As a result, the instructor incorporated a wiki option in the next iteration of the course. "Wiki" is defined here as a collection of loosely structured, collaboratively edited, web-linked content on a particular subject.23 The wiki offers distinct advantages over the traditional discussion-board format used by many distance education courses because it allows for more flexible and collaborative interaction than a linear, "post and response" discussion board.24

The wiki prompt in each lesson begins with the phrase "Be the Ethnographer," inviting students to apply course concepts to their own experiences (see figure 3). Students have the option of commenting on other students' wiki postings or creating a new one of their own. An additional advantage of the wiki option is that it enables students to contribute educational vignettes for both current and future students. That is, the wiki contributions are available for current students to read and, at the end of the course, several contributions are chosen to be converted into scenarios for future iterations of the course. Figure 3 shows an example of a wiki prompt from Lesson 7 of Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication.

Figure 3. Sample wiki prompt

Student-recommended changes to the course, such as the introduction of the wikis, have been compiled on the completion of each iteration of the course thus far, and wiki participation has averaged 77 percent since its introduction. Further, to determine whether the number of contributions to the wiki would increase if students were rewarded for participating, the winter 2012 iteration of the course offered students minimal extra credit (5 extra credit points out of a total 300 points possible for the course) if they contributed to all of the wiki prompts found throughout the course. It is worth noting that wiki contributions increased by over 800 percent, suggesting that very minimal extra credit is sufficient to dramatically increase student participation in the wiki.

Author Lauren Mackenzie recently conducted research to determine whether wiki participation improves the quality of online learning for military personnel.25 Quality of learning was defined along several dimensions: ability of students to apply course material, student grades, retention rate, and student self-reported assessment of the course. For two iterations of the course (N = 232), wiki participation was positively correlated with several important student outcomes.

- First, wiki use has been shown to correlate with increases in overall course grade average, linking the student's participation in an asynchronous exercise to better mastery of course concepts (found in lesson quizzes, a midterm exam, and a final exam). The effects of wiki participation on the final course grade were analyzed in an analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results demonstrated significant positive main effects for participation in the wiki, F (1, 281) = 42.76, p < .01. Thus, students who contributed to the wiki had significantly higher final course grades (M = .85, SD = .08) than students who did not contribute to the Wiki (M = .53, SD = .37).

- Second, wiki use has been shown to also correlate with an increase in scores for applied scenarios. This indicates that students who fully participated in the wiki also performed better on exercises designed to test students' ability to apply the course academic content to real-life cross-cultural decision-making scenarios. The effects of wiki participation on the situational judgment test also were analyzed in a one-way ANOVA. The results demonstrated significant positive main effects for participation in the wiki on the SJT scores, F (1, 227) = 7.65, p < .01. Thus, students who contributed to the wiki had significantly higher SJT scores (M = 5.39, SD = 3.29) than students who did not contribute to the wiki (M = 4.04, SD = 3.21). These results emphasize the importance of continuing to use the wiki and SJTs to improve student learning outcomes.

- Finally, student retention rates, as an indication of course and instruction quality, remained stable, indicating that there was not an adverse impact on retention due to the addition of the wiki option.

Summarizing the key findings from four years of offering online military culture courses yields three observations to consider for future courses:

- Flexibility is key for military students, and the self-paced course option has been the most successful in terms of retention rates and student satisfaction.

- Using frameworks and scenarios that are familiar to military students has yielded positive results. Using situational judgment tests drawn from military students' intercultural experiences and the KSAO framework are two noteworthy examples.

- Providing voluntary opportunities for interaction among students through a class wiki has proven to positively correlate with final course grades and an increase in scores for applied scenarios.

Best Practice: Using Student Wiki Contributions to Create Military Scenarios

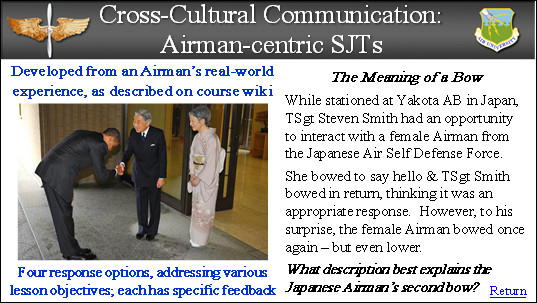

Based on several years of program evaluation, we recommend that military culture courses focus on skills relevant to military personnel, provide tools that help students apply those skills, and give students opportunities for application. Taken together, these three points support the need for scenario-based learning with military students. As with any academic course, it is necessary to provide opportunities for students to demonstrate what they have learned, and we have had success using situational judgment tests to capture and further student learning. As stated earlier , scenarios used in the courses are designed to (1) be consistent with the types of situations students might face on the job or in intercultural interactions while they are stationed overseas, and (2) provide immediate feedback to the student about how optimal each choice is compared to the other options presented. One opportunity to gather a wide range of cross-cultural military experiences has been through the Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication wiki. Figure 4 illustrates how one student's wiki contribution was converted into a situational judgment test devoted to "manifestations of culture" in Japan for the next iteration of the course.

Figure 4. Situational judgment test created from student wiki contribution

The process of creating a new situational judgment test begins with a review of the 900 (approximately) wiki contributions from students to find a story that would bring an Air Force perspective to one of the concepts/skills from Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication. When the instructor found one that looked promising, she then turned to several active-duty and retired Air Force personnel for assistance with turning the wiki contribution into a one-paragraph scenario with correct Air Force terminology. Once the scenario, correct response, and three distracters were written, it was then reviewed for cultural accuracy within the Air Force Culture and Language Center (housing a large staff of professors, Air Force retirees, and active-duty Airmen with expertise in cultures and languages from around the world). After the content was reviewed, the instructor sent the situational judgment test to the student who initially posted the story on the wiki to request his permission to use it (names changed, of course); he was happy to learn his experience had been converted into a teachable moment for other Airmen. Thus, the interactive feature of the course also served the purpose of generating unique, military-centered scenarios to be used in future iterations of the course.

Conclusion

The lessons learned and best practices discussed in this article become more critical as we move into a period of resource constraint in the Department of Defense and as military education moves into a more blended learning environment. There is little doubt that the pendulum of military culture education is swinging decidedly in the direction of distance learning, and the Air Force Culture and Language Center is setting a benchmark in this new direction.

As noted throughout this article, several features of the AFCLC online courses make them potential models for distance education in the DoD:

- Militarily relevant: Students respond best to course content that is both framed using tools that are familiar to them (e.g., OODA loop) and applied to scenarios consistent with the types of situations they are likely to experience as Airmen.

- Self-paced: Students take courses while deployed or stationed all over the world, where Internet connections can be intermittent and time differences can be significant. In order to meet the needs of military students' atypical and unpredictable schedules, asynchronous course offerings are recommended, with voluntary opportunities for student interaction.

- Academically sound: Contributions from subject matter experts in the areas of anthropology, communication, and cultural geography address the interdisciplinary nature of culture. This, in turn, leads to more effective and robust academic content that is taught throughout the semester.

- Systematically assessed: Because the courses reach thousands of students a year, conducting pre- and post-assessment measures for both knowledge and attitude, along with student exit surveys, has been used to continuously improve the course content and design.

The literature on best practices emphasizes the importance of identifying, using, and sharing knowledge within an organization. This article has aimed to contribute to that call in the realm of military distance education with the hope that future online course developers will have as much information as possible to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse military student population.

- "Self-paced" is defined here as an asynchronous course without student-teacher interaction.

- According to the 2010 distance education survey results, Trends in eLeaning: Tracking the Impact of e-Learning at Community Colleges [http://www.itcnetwork.org/attachments/article/66/ITCSurveyResultsMay2011Final.pdf], the national student retention average for online courses is 69 percent. Introduction to Culture typically enrolls 1,000 students per semester, with a 68 percent average retention rate. Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication typically enrolls 300 students per semester, with an 80 percent retention rate.

- See the American Council on Education website for statistics on military students and veterans.

- Lauren Mackenzie and Megan Wallace, "Distance Learning Designed for the U.S. Air Force," Academic Exchange Quarterly, vol. 16 (Summer 2012), pp. 55–60; and Deborah Ford, Pamela Northrup, and Laurie Wiley, "Connections, Partnerships, Opportunities, and Programs to Enhance Success for Military Students," in Creating a Veteran-Friendly Campus: Strategies for Transition and Success, Robert Ackerman and David DiRamio, eds. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009), pp. 61–69.

- See, for example, Robert W. Rowden, "The Learning Organization and Strategic Change," S.A.M. Advanced Management Journal, vol. 66, no. 3 (2001), pp. 11–16; and Carla O'Dell and Jackson Grayson, "If Only We Knew What We Know: Identification and Transfer of Internal Best Practices," California Management Review, vol. 40, no. 3 (1998), pp. 154–174.

- The authors of this article are the course designers, content writers, and professors of record for Introduction to Culture and Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication.

- Speech delivered by President Obama to the Veterans of Foreign Wars, August 2009.

- Montgomery McFate, "Anthropology and Counterinsurgency: The Strange Story of Their Curious Relationship" Military Review (March–April 2005), pp. 24–38.

- In recent years, a variety of publications have spoken to the military's need for language and culture education. See, for example, Maxie McFarland, "Military Cultural Education," Military Review, vol. 85 (March/April 2005), pp. 62–69; Brian Selmeski, Military Cross-Cultural Competence: Core Concepts and Individual Development (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air Force Culture and Language Center, 2007); Allison Abbe, "Building Cultural Capability for Full Spectrum Operations," Army Research Institute Study Report (2008); and Robert Greene Sands, "Language and Culture in the Department of Defense: Synergizing Complementary Instruction and Building LREC Competency," Small Wars Journal (March 8, 2013).

- The AFCLC defines cross-cultural competence as "the ability to quickly and accurately comprehend, then appropriately and effectively act, to achieve the desired effect in a culturally complex environment" (Selmeski, Military Cross-Cultural Competence).

- See the CCAF Point Paper [http://www.au.af.mil/au/ccaf/public_affairs/point_paper.asp].

- This effort was undertaken by Dr. Brian Selmeski, who authored the Quality Enhancement Plan "Cross-Culturally Competent Airmen" [http://www.culture.af.mil/qep] for Air University.

- Gary Klein, Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998); and Giora Keinan, "Decision Making under Stress: Scanning of Alternatives under Controllable and Uncontrollable Threats," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 52, no. 3 (March 1987), pp. 639–644.

- Items were drawn from scales by Karen van der Zee and Jan Pieter van Oudenhoven," The Multicultural Personality Questionnaire: A Multidimensional Instrument of Multicultural Effectiveness," European Journal of Personality, vol. 14, no. 4 (July/August 2000), pp. 291–309; and Hunter Gehlbach, "A New Perspective on Perspective Taking: A Multidimensional Approach to Conceptualizing an Aptitude," Educational Psychology Review, vol. 16, no. 3 (September 2004), pp. 207–233.

- Stefan Hrastinski, "Asynchronous and Synchronous E-Learning," EDUCAUSE Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 4 (October–December 2008).

- See Hunter Gehlbach, Lissa V. Young, and Linda K. Roan, "Teaching Social Perspective Taking: How Educators Might Learn from the Army," Educational Psychology, vol. 32, no. 3 (2012), pp. 295–309; Linn Van Dyne, Soon Ang, and Christine Koh, "Development and Validation of the CQS: The Cultural Intelligence Scale," in Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications, Soon Ang and Linn Van Dyne, eds. (Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe, 2009), pp. 16–38; and Joan R. Rentsch, Allison Gunderson, Gerald F. Goodwin, and Allison Abbe, Conceptualizing Multicultural Perspective Taking Skills, Technical Report 1216 (Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2007).

- Perspective taking is commonly defined as "the ability to take the perspective of individuals within the context of their culture" (see Rentsch et al.).

- Cultural self-awareness as a construct is derived from the metacognitive cultural intelligence scale, which asks people to self-report responses to four items. Two of these are: "I am conscious of the cultural knowledge I use when interacting with people with different cultural backgrounds" and "I adjust my cultural knowledge as I interact with people from a culture that is unfamiliar to me" (Van Dyne, Ang, and Koh, "Development of the CQS," p. 20).

- Intercultural efficacy is derived from Abbe, Geller, and Everett, in which participants self-report on three items. Two of these are: "In general, how effective are you in communicating with individuals from other cultures?" and "In general, how prepared do you feel to interact with individuals from other cultures in the future?" Allison Abbe, David S. Geller, and Stay L. Everett, Measuring Cross-Cultural Competence in Soldiers and Cadets: A Comparison of Existing Instruments, Technical Report 1276 (Arlington, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 2010), p. 8.

- Data from Katie M. Gunther, Jennifer S. Tucker, and Patricia Fogarty, "Social Perspective Taking: A Cultural Analysis Skill for Effective Performance" (poster presented the annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Houston, Texas, April 11–13, 2013).

- Joyce Osland and Allan Bird, "Beyond Sophisticated Stereotyping: Cultural Sensemaking in Context," Academy of Management Executive, vol. 14, no. 1 (February 2000), pp. 65–77.

- Mackenzie and Wallace, "Distance Learning for the Air Force."

- Yoany Beldarrain, "Distance Education Trends: Integrating New Technologies to Foster Student Interaction and Collaboration," Distance Education, vol. 27, no. 2 (2006), pp. 139–153; Brian Morgan and Richard Smith, "A Wiki for Classroom Writing," The Reading Teacher 62, no. 1 (September 2008), pp. 80–82; and Kevin Parker and Joseph Chao, "Wiki as a Teaching Tool," Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge and Learning Objects, vol. 3, no. 1 (January 2007), pp. 57–72.

- Beldarrain, "Distance Education Trends."

- See Lauren Mackenzie and Megan Wallace, "Creating Virtual Communities for Air Force Personnel: A Cross-Cultural Communication Case Study," for a complete analysis of the function and consequences of wiki utilization in two iterations of the Introduction to Cross-Cultural Communication course in Culture, the Flipside of COIN: Cross-Cultural Competence for a 21st Century Military, Robert Greene-Sands and Allison Greene-Sands, eds. (Lanham, MD: Lexington, to be published late 2013).

© Lauren Mackenzie, Patricia Fogarty, and Angelle Khachadoorian. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license.