Without sustained care and attention, the digital works that delight and inform our lives quickly decay into digital dust. The Digital Preservation Network provides a structure for vetting and protecting digital treasures for future generations.

Imagine that this is the opening to a movie, rather than the first lines of an article. As the scene opens, snow is falling on a picturesque village nestled somewhere in the mountains. The snow falls gently at first. Skis, skates, and sleds come out of hiding, and there is a flurry of activity as the village comes alive with the possibilities that fresh snow brings. Snow forts pop up. Blocks of ice are transformed by axe and chisel into shimmering works of art. Frozen castles dot the landscape. Hot chocolate and good cheer flow like rivers.

But the snow doesn't stop. Its soft gentle caress soon gives way to something more troubling. Edges blur. Familiar objects become difficult to recognize. Trees bend under the weight. Roofs groan. Timbers creek. The snow just keeps falling.

The villagers start to cast wary eyes toward the mountains and begin shoveling—slowly at first, but soon at a furious rate. Still the snow falls.

As the movie's opening credits fade, we hear an ominous rumble and see a hint of movement in the snowpack. In the blink of an eye, the avalanche begins. With terrifying speed, a torrent of snow cascades down the mountains. It snaps trees, destroys roads, and buries the village. All is lost. Where once the village stood, there is now only snow and the darkness of the approaching night.

*******

Outside the movie it is also snowing—hard. But the snow we face is not born of anything as tangible as water. It is made up of the digital bits and bytes that embody and convey the ideas, expressions, and discoveries of this century. In laboratories, libraries, and studios, physical objects are giving way to their digital counterparts. Essays and books, even the ones that we read in familiar hard copy, are digital first. Scientific instruments are producing data sets of sizes that stagger the imagination. Art, in all its many forms, has found its way to the World Wide Web.

The digital revolution is fueling unprecedented growth in all areas of research and expression. It enables amateurs to make important contributions to science. It changes the ways artists make and distribute their works. It allows anyone with talent and an Internet connection to publish. It is transformative.

But the digital revolution also presents a problem. Digital expressions, despite both their ubiquity and their centrality to modern life, whether they are words, data, or images, are inherently fragile. Unlike text, for example, which can be stored in the appropriate environment and left alone for long periods of time, digital records require ongoing attention. Left alone, digital records experience entropy and rapidly degrade. Moreover, as new technologies come along, digital records must be migrated to new hardware and software platforms; if not, the ability to "read" them is lost. Without sustained care and attention, the digital works that delight and inform our lives quickly decay into so much digital dust—a fact known firsthand by anyone who has tried to recover a file from a floppy disc or obsolete word processor.

Consider the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Begun in 2000 and completed in 2008, SDSS- I/II covered 25 percent of the sky, mapped 930,000 galaxies, released more than 100 terabytes of data to the scientific community, and resulted in more than 2,000 articles and 70,000 citations. (SDSS-III began in 2008 and will continue until 2014.) That is a lot of "snow." More important, it is precious snow. Once lost, astronomical data cannot be replaced. The last supernova to happen in our galaxy occurred in 1604. The next nearest supernova occurred almost 400 years later in 1987. To say that this is rare and highly valuable data is to understate the situation by several orders of magnitude. Data about astronomical events cannot be re-created. It represents a moment in time—captured, we hope, for eternity.

The library community is, of course, aware of the dangers that come with digital records, and librarians have been investing in a variety of strategies designed to mitigate the threats. Many libraries have deployed institutional repositories. Consortia such as HathiTrust and CLOCKSS have been created to take advantage of the economies of scale and geographic diversity that networks enable. Portico was founded with the intention of providing one-stop insurance against the almost certain possibility that some publishers will fail to provide perpetual access to the e-journals and e-books that libraries have purchased. The MetaArchive Cooperative was established to encourage individual institutions to develop their own preservation practices and resources and share them across institutions. Taken together, these efforts show that there is some serious shoveling that is succeeding in moving a lot of digital snow.

But is it enough? Will a strategy that relies on uncoordinated and independent preservation initiatives, a strategy that served us well in the analog world, ensure that the treasures of this generation are available to the next? The answer is almost certainly "no." Local and isolated preservation efforts will be particularly hard-pressed to realize the benefits associated with operating at scale, much less keep pace with the rapid growth in digital content. And digital records preserved in a single environment—no matter how robust—are always one major failure away from being lost forever.

Sometimes, failure is due to a cascading series of technical problems. How many career IT professionals can point to incidences of information loss in their data center after a disk failure (perhaps due to hardware breakdown or silent corruption) only to discover that the tape backups were not properly configured? Other times, failure comes about because of changing political climates. In 2002, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina opened with the ambition of re-establishing the great Royal Library of Alexandria of antiquity with a focus on digital, as well as traditional, collections. Ten-plus years later, some fundamentalist groups view it as a symbol of modernity and secularism and are calling for its destruction.

Still other times, failure is caused by financial/organizational threats. Consider again the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). Both the University of Chicago and Johns Hopkins University currently have formal agreements with the Astrophysical Research Consortium to provide archiving services for the data from the SDSS-I/II. Although that is clearly good news, the funding expires this year. Data that took eight years to collect and that has scientific value measured in centuries has a preservation horizon that expires this year. The Sloan Foundation may well see fit to continue funding the initiative beyond 2013, but it might not.

What these examples highlight is that isolated preservation efforts are inherently at risk. Without coordinated replication across a diversity of preservation environments, digital collections are one catastrophic, economic, technological, or organizational failure away from irrevocable loss.

A growing number of institutions (fifty-eight at the time of this writing) are joining the Digital Preservation Network (DPN—pronounced "deepen") to address these concerns by leveraging the investments the library community is making in digital preservation. At the heart of DPN is a commitment to replicate the data and metadata of research and scholarship across diverse software architectures, organizational structures, geographic regions, and political environments. Replication diversity, combined with succession rights management and vigorous audit and migration strategies, will ensure that future generations have access to today's discoveries and insights.

DPN Overview

Currently in its start-up phase, DPN is building a digital preservation backbone that connects five existing (or soon to exist, in the case of APTrust) preservation-oriented repositories: the Academic Preservation Trust (APTrust), Chronopolis, HathiTrust, Stanford Digital Repository (SDR), and the University of Texas Digital Repository (UTDR). Collectively, these five are known as the DPN nodes. The five nodes are located in different parts of the United States, and each brings with it a distinct architecture, hardware platform, and organizational/financial structure.

By linking the repositories and developing frameworks around audit, transport, and intellectual property management, DPN will make it possible to create "dark" copies (i.e., no end-user access) of the content across the various nodes while maintaining high confidence in the integrity and retrievability of that content.

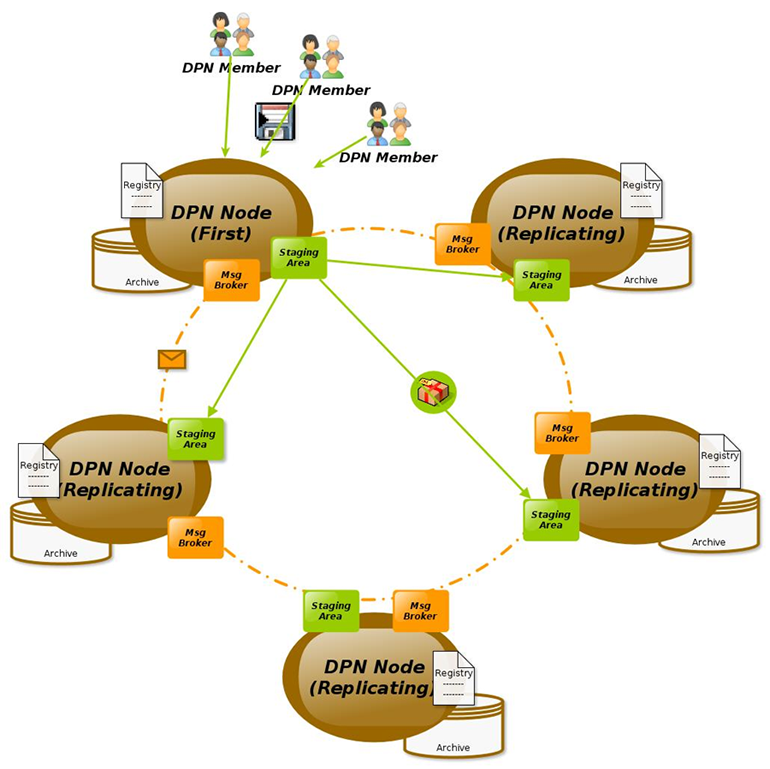

Initially, DPN-bound content will be replicated across a minimum of three nodes, ensuring that a failure of any single node leaves a minimum of two verified copies that can be used to repopulate the failed node or to build and populate a new node in the event of catastrophic or permanent loss. Figure 1 shows a conceptual rendering of the DPN structure.

Figure 1

Diagram Courtesy of Andrew Woods

Though intimately connected with the technological challenges that come with digital preservation, DPN is less about technology and more about building a sustainable ecosystem in which digital preservation can scale and evolve. In that sense, it is similar in approach to that taken in 1996 by leading research universities when they decided to build and own Internet2. Confronted with a plethora of proposed solutions to increase network bandwidth coming into campuses, and taking advantage of the consolidation that was happening with the emergence of regional networks, thirty-four universities banded together to fund the creation of a high-speed research and education network. At its original launch in 1999, the Internet2 Abilene Network had a total capacity of 2.4 Gbps and connected approximately 70 member institutions. At that time, it was considered one of the most advanced networks in the world. By today's standards, of course, its original capacity is tiny and grossly inadequate.

But here is where Internet2 thrives. As a federation that aggregates demand and leverages standards and practices at scale, Internet2 has consistently been able to evolve. As new technology comes along, Internet2 upgrades and adapts. Today, the Internet2 backbone has a total capacity of 8.8 Tbps. Perhaps more important, Internet2 has moved beyond simply providing a physical network and now offers a host of services (e.g., authentication schemes, dedicated wave service, and web-based services such as Box.net) that leverage the aggregated demands and requirements of its member institutions. Owned by and for the academy, Internet2 provides a high-speed backbone that fuels research, discovery, and dissemination. DPN is its complement, providing assurance that discoveries, once made, are being preserved for future generations in an environment that is owned and controlled by the academy.

DPN Operations

Once DPN is constructed, its members and other depositors will be able to add digital assets to the network by working with an individual DPN node to ingest and preserve content. This content is then replicated to other DPN nodes, which together form a heterogeneous network of secure, trustworthy, dark digital archives, each operated under diverse geographical, organizational, financial, and technical regimes. Robust (bit) auditing and repair functions will ensure the fixity of content over time. Intellectual property agreements will ensure the succession of rights to use of the content through the network in the event of dissolution or divestment of content by the original depositor and/or archive. In other words, DPN creates a diverse dark archive from which content can be retrieved should catastrophe strike. It provides protection against disaster and neglect. It creates a framework by which the academy can avoid the downstream creation of countless new orphan works. It forms a foundation against which we can build digital workflows that are scalable and sustainable. It vests stewardship in the hands of higher education institutions.

By illustration, a typical flow of primary interactions in DPN might take the following form:

- Step 1. DPN Members will work directly with an individual DPN node to negotiate contracts, determine service levels, and deposit materials into DPN via the "First Node." Service levels and contracts will reflect "standard" DPN services; they may also reflect the First Nodeʼs unique offerings in terms of access (remember, DPN is a dark archive that links together and makes preservation copies of the material in the access-oriented preservation repositories), hosting, or other services.

- Step 2. DPN will replicate the content from the First Node (the contentʼs point of entry into DPN) to other DPN nodes (known in this case as "Replicating Nodes"). Content in Replicating Nodes will be held dark and inaccessible except for preservation actions.

- Step 3. DPN bit auditing and repair functions will continuously monitor the integrity of copies across all nodes and will detect and repair corruption, errors, and data loss on an ongoing basis.

- Step 4. DPN First Nodes will be able to restore copies of content from Replicating Nodes in the event the First Nodeʼs copies are lost or corrupted. This shall include

- restoration of individual content;

- restoration of sets of content; and

- restoration of the entire contents of the First Node.

- Step 5. DPN will redistribute preserved content as nodes enter and leave the network, ensuring longevity of content and continuity of preservation services over time.

Throughout the process, DPN will provide a platform to preserve and manage sufficient identity, administrative (including legal and contractual), technical, and descriptive metadata to enable the brightening of content after succession, independent of any contributions or participation by the First Node or original depositor in the future.

DPN Benefits

DPN is designed to preserve digital information for the academy by establishing a network of heterogeneous, interoperable, and trustworthy digital repositories (DPN nodes) to provide preservation services under a coordinated and diverse technical, service, and legal framework. DPN nodes will operate in a secure manner to protect the integrity of the processes, transport, and content that DPN holds. As such, the creation of DPN provides multiple benefits to society, the academy, and DPN members.

- Resilience. As the "archive for archives," DPN provides a safety net of redundant copies of content stored in multiple, independently operated repositories. This helps preserve content in the event an archive no longer performs its function as an archive (due to loss of will or change in mission), as well as ensures against the failure of any single repository for technical, economic, legal, or catastrophic reasons.

- Succession. Content preserved in DPN, as a preservation network for the academy and by the academy, will be covered by preservation succession rights that will allow the content to be used in the future by the academy after the dissolution of the source of the content.

- Economies of scale. DPN will be able to leverage significant resources and offer them to member institutions in ways that would not be economically feasible at individual institutions.

- Efficiency. By establishing a network of proven, trustworthy digital repositories with robust replication, fixity services, and an established contracts framework, DPN can lighten the load on individual academic/research repositories that need, but have not built out, their own preservation environments.

- Extensibility. The network provides a business, technical, and legal framework that is designed to evolve over time and adapt to changes in the environment that may affect approaches to ensuring the preservation of information over the long term.

- Security. Information and process security is integral to DPN's design. By explicitly acknowledging and addressing the threats using agreed-upon security best practices, DPN safeguards its content against both exposure and corruption—accidental or intentional—in transmission or at rest in any node.

Can We Afford DPN?

At one level, the answer to the question of whether we can afford DPN is simply that we have no choice. Without the coordinated effort that DPN embodies, existing preservation silos are one disaster away from oblivion. But the good news is that coordinated action is less expensive than the laissez-faire world we currently inhabit. One of the clear lessons that college and university CIOs have learned is that many of the problems faced by institutions today are best solved at a scale that is larger than any single institution. The economics of networks often dictate large infrastructure costs with small marginal use costs. Building enterprise storage, for example, requires a significant investment. But once the infrastructure is in place, storing a byte costs the same as storing a petabyte, assuming the system has been built for a petabyte of capacity. Moreover, once that infrastructure is in place, it can be extended at much lower marginal costs. Adding a second petabyte of storage will almost certainly cost less than creating a petabyte from scratch.

The economics of scale are relevant to a growing number of library operations. Digital preservation, aggregated access, shared information systems, and common compliance challenges all lend themselves to an approach that leverages scale and interinstitutional collaboration. The bottom line is that in the world of network-enabled services, the institutional default should be to look for opportunities to solve the problems at scale across institutions. DPN can provide a foundation for this type of coordinated activity. With the DPN network, we gain safety with less expenditure of local resources.

There is another sense in which DPN is affordable. One of the challenges in the preservation space is the plethora of approaches that are being taken to address various pieces of the preservation puzzle. Given the fact that we are still in the early stages of making the transition to a more fully digital world, there is much to celebrate about a landscape populated with experiments and demonstrations. But it is also a very confusing landscape to navigate. How should we pick among the many competing alternatives? If a college or university has invested in Portico, for example, must it also invest in HathiTrust? What about DSpace?

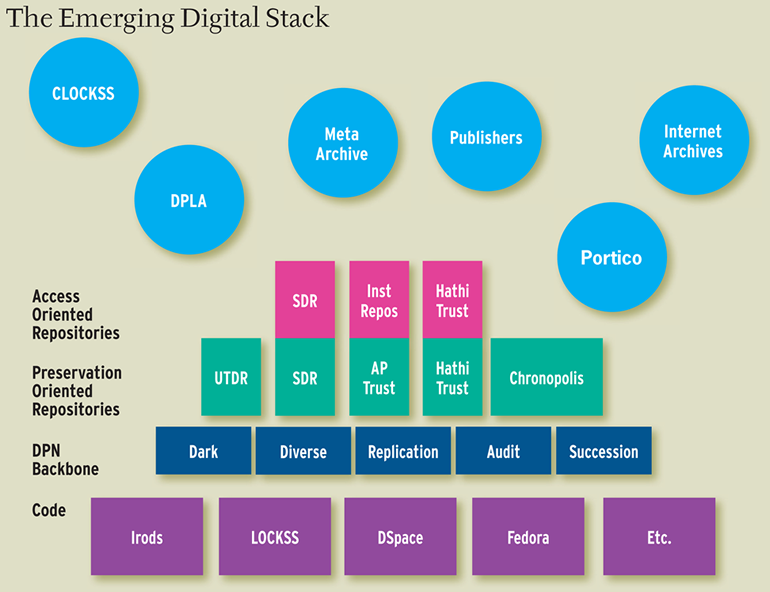

One of the advantages of the DPN approach is that it starts to bring coherence by leveraging investments that members of the community have already made and by creating paths to connect members with each other. With DPN in the picture, it becomes possible to view various preservation activities as a "stack" of services and to begin to discern how to shape investments in preservation services.

Figure 2

As seen in Figure 2, at the bottom of the "stack" are various sets of code that power a diverse set of preservation repositories. At the next layer up (dark blue) are the DPN services that connect a finite number of preservation-oriented repositories. Above that sits a layer that provides end-user access. In some cases, like HathiTrust, the same repository provides both end-user access and preservation services. In other cases, like APTrust, the preservation repository is primarily dark and the connected institutional repositories provide access to end users.

What the emerging stack helps to clarify is the opportunity to use DPN to bring greater coherence and interoperability to the digital preservation space. Whereas most preservation activities do not currently connect to DPN (illustrated by the activities in the blue circles), the creation of DPN will provide an opportunity to be increasingly strategic in choosing which initiatives to support and to be intentional in connecting them. More is not necessarily better. What is necessary is coordinated diversity.

Coda

At its most basic level, scholarship is an enduring public conversation among scholars. The particular form of that conversation, whether it is based in data, rhetoric, or creative expression, matters less than the fact that it is both public and enduring. In the analog world, we know how to make this happen. Faculty members and their students publish, libraries collect and preserve, and the works are thereby made accessible to current and future generations. The workflows that sustain this process have evolved over the last six centuries and are now so deeply ingrained that they are practically invisible—complicated, to be sure, but deeply understood and well practiced.

The transition from analog objects to digital objects puts that whole workflow up for grabs. In the networked world, access continues to play a defining role, but the nature of access has changed. Simple access has become ubiquitous—expensive, but ubiquitous. What remains elusive is durable access to the analog and digital works currently in the collections. Scholarship and research workflows are increasingly characterized by rapidly changing objects, massive data sets, and a host of third parties eager to provide a variety of services in exchange for proprietary pathways that lock up content and render it fragile and almost certainly inaccessible to future generations. Libraries, and the academy more generally, must get ahead of this curve. If we fail to lead through the transition, we will rapidly re-create the unsustainable models that have emerged from the publishing practices of yore. By providing an anchor at one end of this workflow, DPN provides a structure against which we can leverage aggregation and design procedures for vetting and protecting digital treasures for future generations.

© 2013 James L. Hilton, Tom Cramer, Sebastien Korner, and David Minor. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 48, no. 4 (July/August 2013)