Online learning has provided a platform for rethinking delivery models, yet much of accreditation is not designed to account for these new approaches.

Enormous change is under way in higher education, driven by a perfect storm of crisis (around cost, access, quality, and funding), technological innovation and what that innovation makes possible, the growing presence and influence of for-profit providers, abuses (of various kinds), opportunity, and workforce development needs in a global and technological context. Any one of those challenges might fill an agenda for a commissioners' retreat or a small conference, but accreditors now wrestle with all of these various forces across a broad landscape of change and urgency. They do so at a time when they are already being buffeted by criticism that they are too lax in regulating for-profits and too slow in addressing deeply troubled institutions and by pressure for change from a Department of Education that wants more rigor and oversight even as it seeks ways to support more innovation in higher education.

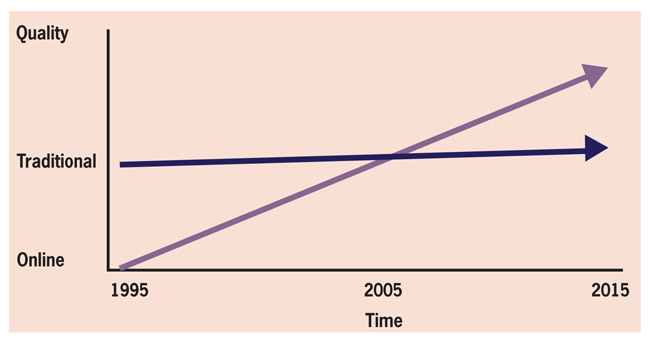

Future historians of this period, possessing the clear-sightedness that only time provides, will likely point to online learning as the disruptive technology platform that radically changed an industry largely unchanged in terms of its core delivery of service (i.e., teaching and learning) since the cathedral schools of medieval Europe. Many in higher education today are looking to new technology-based or at least technology-enhanced solutions for their problems, and online learning has in many ways paved the way. Although many non-profit institutions are just now catching up with online programs, often entering that market because of economic pressures, online learning is already well understood, well established, and well respected by those who genuinely know it. In fact, as Clayton Christensen's The Innovator's Dilemma predicted,1 the question of fifteen years ago—"How can we make online learning the equal of traditionally delivered learning?"—has been reversed. We now ask, "How can we make traditionally delivered learning the equal of the best-designed online learning?" This is because disruptive innovations always start as inferior to incumbent models, but their technological core improves at a steeper curve than that of the incumbent models (which in this case has remained fundamentally the same and has thus resisted productivity improvement, as explained in part by William Baumol).2 Eventually, the disruptive innovations surpass the incumbent models.

As Christensen also predicted, when traditional faculty teach online, they bring back to their traditional classrooms new pedagogical methods and technologies; online education is thus actually helping to improve traditional delivery models. Coursera co-founder Andrew Ng recently reported the same phenomenon for instructors in MOOCs,3 the most traditionally structured of online courses (biased, as MOOCs are, toward "sage-on-the-stage" teaching and toward more teacher-centered than student-centered structures, at least for now).

Accreditors have largely come to understand online learning and readily assess it as part of any institutional review. State regulators are another story, however. The crazy quilt of fifty different state regulatory approaches, many of them built in anticipation of on-the-ground physical campuses and flavored with a protectionist bias, is actually impeding access to high-quality online programs—but that's another sad story best saved for another day. What we are now seeing in higher education is a new wave of innovation that uses online learning, or at least aspects of it, as a starting point. The meteoric growth of the for-profit sector, the emergence of MOOCs, new self-paced competency-based programs, adaptive learning environments, peer-to-peer learning platforms, third-party service providers, and the end of geographic limitations on program delivery all spring from the maturation of online learning and the technology that supports it. Online learning has provided a platform for rethinking delivery models, yet much of accreditation is not designed to account for these new approaches.

Perhaps most important, this new wave of innovation relies on a disaggregation within higher education, a common phenomenon in mature industries but one that the higher education industry has remarkably resisted for centuries. Indeed, one could argue that the core of the educational enterprise has always been vertically integrated in the body of the faculty. That is, faculty members have thought up new courses and programs, developed syllabi, outlined learning objectives, "curated" the necessary content and learning artifacts (mostly choosing books and chapters and articles), walked the proposed courses/programs through necessary approvals (governance), taught the courses/programs, advised students, stepped in when students needed help, administered assessments and graded performance, and periodically revised the course/program. That was the way of the world until online technology entered the picture.

Online learning has disaggregated the model. Today, various players perform various aspects of what was once the exclusive province of faculty:

- A faculty member might be hired as the subject matter expert to develop a course but never teach it or be involved in it again.

- Faculty might be hired to teach a course that is already developed and handed to them, with little room for them to change the course (common in large-scale programs where standardization is important).

- Third-party providers (e.g., Smarthinking) might provide student tutorial help.

- Students might turn to a peer-to-peer learning network (e.g., OpenStudy) instead of to faculty when they run into trouble.

- Adaptive learning technologies might intelligently guide a student's pathway through the learning content.

- The person assessing a student's work might not be the faculty member teaching the course (e.g., Western Governors University) and some MOOCs using peer assessment).

- Self-guided learning models (e.g., the College for America program at Southern New Hampshire University) might have no faculty instruction at all.

We do not properly acknowledge the great displacement of traditional faculty in the new delivery models, though we know that when technology enters a "craft" profession, the highly skilled and expensive "craftspeople" at the heart of that industry will see their world irrevocably changed. This will be much less true for faculty members in research, elite, and residential "coming of age" programs, but certainly it will be true for those teaching at other types of institutions and those involved in the education of working adults. Students in the increasingly expensive residential college experience, which so much shapes our myth of higher education, represent less than 20 percent of all college students. Slightly more encouraging is that we will see new and different roles for those faculty members not lucky enough to be situated in the research, elite, and/or residential sectors of higher educations—even though those roles are not the ones that inspired many faculty to enter academia.

Disaggregation plays out in other areas as well, including credentials, non-institutional faculty, and the integrated institution.

Credentials. Part of the vertical integration in higher education was due to the fact that colleges and universities fully "owned" the credentialing that came at the end of the educational process. However, today we see growing acceptance of prior learning assessment (PLA) at the front end of the learning process. For example, the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL) has launched a new virtual PLA service, LearningCounts; though still largely under the control of the institutions, it can be accessed by individual students. In addition, numerous industry certifications are often pulled into the learning equation, and there is much discussion of alternative credentialing, especially the notion of badges. MOOC (Massive Open Online Courses) providers are sorting through the kinds of credentials they might offer, and industry stalwarts like the American Council on Education (ACE) have signaled their willingness to work with MOOC providers on assigning credits. Apparently, traditional higher education may be losing some of its monopoly on credentialing, if not in the critical arena of Title IV funding.

Non-Institutional Faculty. Faculty have always been somewhat like independent contractors, working within and thus affiliated with their institutions. However, Sebastian Thrun's 2011 departure from his home institution, Stanford, to create Udacity, a for-profit MOOC provider, may signal new possibilities for how faculty members are situated within the industry. For-profit StraighterLine has announced a model for "self-employed" faculty to teach courses: faculty set their own price models and share the tuition revenue. Similarly, Udemy offers 5,000 courses in which the professor sets the fee and shares 30 percent of the revenue with the company. In yet another variation of this theme, Antioch University has announced that it will offer college credit for Coursera courses, a model that has an outside faculty member offering an Antioch accepted/licensed course (at least in terms of validation through credit) while Antioch provides advising and other learning support. Although these new models are not likely to have a significant impact for some time, if at all, they reinforce the notion of learners "grazing" or assembling their learning from multiple sources, some of which may be newly independent faculty providers.

The Integrated Institution. In the past, institutions largely managed all of their own activities, with perhaps a few exceptions (e.g., food service, maintenance, marketing materials). Today, there is an enormous rush into the higher education services sector, with massive for-profits like Pearson either investing in or acquiring for-profit companies that manage large parts of an institution's activities, ranging from its learning management system (LMS) to marketing activities to admissions and financial aid processing to content and course development to tutoring to . . . . As cash-strapped institutions struggle to establish themselves in the new online marketplace, they are increasingly turning to third-party providers for some or all of what they need. Venture capitalists, entrepreneurs, and traditional publishers (now re-inventing themselves as their print world is being disrupted) are pouring money into the opportunity: Pearson's $650 million acquisition of Embanet+Compass; John Wiley & Sons' $220 million acquisition of Deltak.edu; and in a reverse of this dynamic, Apollo Global Management's $2.5 billion acquisition of McGraw-Hill Education. Accreditors routinely ask institutions to demonstrate control and quality in areas that are increasingly being contracted out to for-profit providers. That expanded use of third parties poses interesting questions.

Overall, accreditation has been based on a review of an integrated organization—the college or university—and its activities. These were largely cohesive and relatively easy-to-understand organizational structures in which almost everything was integrated to produce the learning experience and degree. Accreditation is now faced with assessing learning in an increasingly disaggregated world with organizations that are increasingly complex, or at least differently complex, and that include shifting roles, new stakeholders and participants, various contractual obligations and relationships, and new delivery models. There is likely to be increasing pressure for accreditation to move from looking at the overall whole—the institution—to considering smaller parts within the whole or even alternatives to the whole: programs, providers, and offerings other than degrees, perhaps provided by entities other than traditional institutions. In other words, in an increasingly disaggregated world, does accreditation need to become more disaggregated as well?

MOOCs might serve as one example. For all the attention that MOOCs have received this last year (most recently, Thomas Freidman's gushing endorsement in the New York Times),4 I remain an intrigued skeptic. MOOC providers often ignore that their principal attraction is their elite brand affiliations. If a local state college offers a MOOC, it is more likely to be a SOOC (Small Open Online Course). But when MIT or Harvard or Stanford, brands built on saying "no" to almost all interested parties, offer free (!) courses to all, it is hardly a surprise that so many enroll. Their numbers are impressive, on the one hand, and also not very interesting or surprising, on the other. MOOCs have problems as well. They reify very traditional educational notions: sage-on-the-stage teaching, the traditional semester structure and three-credit-hour model, and a focus on content over learning. They are most deficient in the areas that adult learners require to be successful: learner support, motivation and persistence, the social aspects of learning, and the other, messy human aspects of learning. However, in their defense, I agree that MOOC providers are forging new ground, that it is still early in the development of the models, and that they are thinking hard about these issues. As pointed out earlier, disruption theory tells us that the early iterations of new models often are not very good but that the improvement curve is steep and fast. A lot of very smart people are working on MOOCs. As for accreditation, ACE is exploring how to provide transcript credit to MOOCs, as noted above. Is this not a kind of accreditation at the course level and, thus, disaggregated accreditation?

More profound, if less discussed, is the emergence of competency-based education (CBE). College for America (CfA), a CBE program at SNHU, is the first of its kind to wholly move from any anchoring with the three-credit-hour Carnegie Unit that pervades higher education (shaping workload, units of learning, resource allocation, space utilization, salary structures, financial aid regulations, transfer policies, degree definitions, and more). The irony of the three-credit hour is that it fixes time while it leaves variable the actual learning. In other words, we are really good at telling the world how long students have been sitting at a desk, and we are really poor at saying how much students have learned or even what they learned while sitting at that desk. CBE flips the relationship and says: let time be variable, but make learning well-defined, fixed, and non-negotiable.

In the CfA program, there are no courses. There are 120 competencies—"can do" statements, if you will—precisely defined by well-developed rubrics. Students demonstrate mastery of those competencies through completion of "tasks" that are then assessed by faculty reviewers using the rubrics. Students can't "slide by" with a C or a B; either they have mastered the competencies, or they are still working on them. When they are successful, the assessments are maintained in a web-based portfolio as evidence of learning. Students can begin with any competency at any level (there are three levels, moving from smaller, simpler competencies to higher-level, complicated competencies) and can go as quickly or as slowly as they need to be successful. The program costs $2,500 per year, so an Associate's Degree can be earned for $5,000 if a student takes two years and for as little as $1,250 if the student completes the required competencies in just six months (an admittedly formidable task for most). CfA is the first program of its kind to be approved by a regional accreditor, NEASC, and is the first to seek approval for Title IV funding through the "direct assessment of learning" provisions. At the time of this writing, CfA has successfully passed the first-stage review by the U.S. Department of Education and is moving through the approval process.

The CBE movement offers a radical possibility: that traditional higher education may lose its monopoly on delivery models. If we can say with certainty what constitutes learning and how we know for sure that students have mastered that learning, we should then be much less concerned with how a student gets there. Accreditors have put more emphasis on learning outcomes and assessment for some time now, but the CBE movement privileges them above all else. When we excel at both defining and assessing learning, we open up enormous possibilities for new delivery models, creativity, and innovation. It is not a notion that most incumbent providers welcome, but in terms of finding new answers to the cost, access, quality, productivity, and relevance problems that are reaching crisis proportions in higher education, CBE may be the most dramatic development in hundreds of years. For example, the path to legitimacy for MOOCs likely lies in competency-based approaches. Although MOOCs can readily tackle the outcomes or competency side of the equation, they face the formidable challenges of reliable, trustworthy, and rigorous assessment at scale (at least while trying to remain free). Well-developed CBE can also help undergird the badges movement, demanding that such efforts be transparent about the claims associated with a badge and about the assessments used to validate learning or mastery.

The CBE movement may provide accreditors with a framework for fundamentally rethinking assessment. In this new framework, accreditors would look harder at learning outcomes and competencies and at the claims an entity is making for the education it provides and the mechanisms it uses for knowing and demonstrating that the learning has occurred. The good news is that such a dual focus would free accreditors from concentrating solely on inputs and organization and stakeholder roles and governance and would allow for the emergence of all sorts of new delivery models. The bad news is that we are still working on how to craft well-designed learning outcomes and how to conduct effective assessment. Both are harder than many think.

A stronger focus by accreditors on outcomes and assessment leads to additional key questions:

- How will accreditors rethink standards to account for the far more complex and disaggregated business models that might have a mix of "suppliers"—some for-profit and some non-profit—and that look very different from traditional institutions?

- Will they accredit only institutions, or does accreditation have to be disaggregated too? Might there by multiple forms of accreditation: for institutions, for programs, for courses, for MOOCs, for badges, and so on? At what level of granularity?

- CBE programs are coming. College for America is one example, but some twenty other institutions have announced efforts in this area, major foundations are lining up behind the effort (most notably the Lumina Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), and the Department of Education appears to be relying on accreditors to attest to the quality and rigor of those programs. Although the Department of Education is moving cautiously on this question, accreditors might want to think through what a world untethered to the credit hour might look like. Might there be two paths to accreditation: the traditional "institutional path" and the "CBE path," with the former looking largely unchanged and the latter using rigorous outcomes and assessment review to support more innovation than allowed by current standards? According to innovation theory, the new CBE accreditation pathway would eventually improve the incumbent accreditation processes and standards.

This last point is important: accreditors need to think about their relationship to innovation. If the standards are built largely to assess incumbent models and are enforced by incumbents, they must be—by their very nature—conservative and in service to the status quo. On the other hand, never before has the popular press (and thus the public and the policy-makers) been so consumed with the problems of traditional higher education and so intrigued by the alternatives. In some ways, accreditors are being asked to shift or at least expand their role to accommodate these new models.

A new path for CBE accreditation would likely focus on three key areas:

- The learning outcomes or competencies—looking hard at the clarity of claims, definitions and rubrics, rigor, levels of mastery, scope of learning, the basis for the competencies, and more

- The assessment of mastery—looking hard at mastery assessment, validity, rigor, and more

- Integrity—looking hard at how the program ensures that the students taking the assessments are those who enrolled, that cheating and fraud are prevented, and that funding support is appropriate and goes to actual demonstrated learning

Programs seeking CBE accreditation should commit to greater transparency, clearer performance metrics, and fuller disclosure than required by current accreditation regimens. Such an approach could go a long way to addressing concerns from the Department of Education and should help prevent the abuses that accompanied the growth of online programs over the last fifteen years.

President Barack Obama fired a very loud shot across the bow of traditional accreditation in his State of the Union address on February 12, 2013, and in the supporting outline of his domestic policy plan. In a now much-discussed passage, the plan states: "The President will call on Congress to consider value, affordability, and student outcomes in making determinations about which colleges and universities receive access to federal student aid, either by incorporating measures of value and affordability into the existing accreditation system; or by establishing a new, alternative system of accreditation that would provide pathways for higher education models and colleges to receive federal student aid based on performance and results."5 It is not clear whether the Administration has concrete plans yet for what the "alternative system of accreditation" might look like, but the emphasis on performance and results shifts the focus of any such system to outputs instead of inputs.

If regional accreditors are unable to rise to the challenge, they may find themselves tethered to incumbent models that are increasingly less relevant to higher education. New, alternative accreditors may emerge, as President Obama called for in his domestic policy plan. In other words, the accreditors themselves might be disrupted. There is time. As has been said, we frequently overestimate the amount of change to come in the next two years and dramatically underestimate the amount of change ahead in the next ten years. The time is now for regional accreditors to re-engineer the paths to accreditation to at least offer an alternative outcomes-based option for accreditation. In doing so, they not only will be ready for that future, but they can help usher it into reality.

This article is based on writing produced for the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) as part of a convening to look at the future of accreditation.

- Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator's Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997).

- William J. Baumol, "Health Care, Education and the Cost Disease: A Looming Crisis for Public Choice," Public Choice, vol. 77, no. 1 (September 1993), pp. 17–28.

- Andrew Ng, "Learning from MOOCs," Inside Higher Ed, January 24, 2013,.

- Thomas Friedman, "Revolution Hits the Universities," New York Times, January 27, 2013,.

- Barack Obama, "The President's Plan for a Strong Middle Class and a Strong America," The White House, Washington, D.C., February 12, 2013.

© 2013 Paul J. LeBlanc. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 48, no. 2 (March/April 2013)