Debates about MOOCs and their attendant controversies continue to proliferate. What administrators and IT leaders in higher education need, however, is an overview of MOOCs and information resources to help fathom what they mean for institutions.

Judith A. Pirani is a consultant at the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) and president of Sheep Pond Associates.

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) remain higher education's hot and sexy topic, influencing discussion and media, and creating conjecture and controversy. Nearly every publication and pundit has offered a view on the subject, resulting in an avalanche of information for busy IT leaders and others who want to discern what all this means for their institutions.

This compendium attempts to lend a helping hand, recounting perspectives, research, and resources gleaned from a search of EDUCAUSE and other published sources. It is by no means absolute, but rather aims to provide a starting point of discovery for interested parties.

Past, Present, and Future: the MOOC's Place on the E-Learning Continuum

A quick look into e-learning's development offers perspective on today's MOOC phenomenon, for MOOCs are not a transformation in and of themselves — they are an element in a long, complex, and nuanced transformation process.1

A decade ago, the EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research (ECAR) published its first report about e-learning, Supporting E-Learning in Higher Education.2 Looking back, it was a time when e-learning3 was on the cusp of reshaping higher education. Learning management systems (LMSs), online communications and information access, and network bandwidth were becoming robust and accessible enough4 to alter the concept of course and classroom.

E-learning had become a standard component in many courses, and technology applications were no longer limited to the classroom; institutions were also replacing some classroom sessions with virtual sessions or fully replacing classroom courses with online courses.5 As e-learning courses multiplied, institutions began to contemplate e-learning's impact on infrastructure, faculty and student technical skills, and course design support.6

Over time, the triumvirate of tools, access, and network became increasingly sophisticated, accessible, and robust, making e-learning more feasible to fold into the educational experience. Students and institutions alike took notice. ECAR's annual student and IT studies,7 which track students' use of technology over time, show the growing student participation in online learning:

- In 2008, 15 percent of students said they had taken a class completely online.8

- By 2013, almost half (46 percent) of student respondents had taken any online course in the previous year.9

Institutions responded to student demand, offering more online courses, as well as online degree and certificate programs. ECAR's 2013 report on e-learning, The State of E-Learning in Higher Education: An Eye Toward Growth and Increased Access, notes that online courses are ubiquitous, with more than 80 percent of institutions offering several courses online and more than half offering a significant number courses online.10 With experience came understanding of online learning's institutional role; today, the ECAR study reports more than two-thirds of academic leaders believe that online learning is critical to their institution's long-term strategic mission of institutional growth and increased access.11

Technology continues to push e-learning and higher education boundaries further as computer and Internet access expands globally, higher network bandwidth enables richer educational experiences, and the emergence of social networking introduces greater engagement among course participants. An outgrowth of these advancements is the MOOC, an emerging model for delivering learning content online to an unlimited number of students.12 (For a brief backgrounder on MOOCs, see sidebar 1.)

This unprecedented scaling of the educational experience has attracted considerable attention, and — much like the early phases of e-learning — has sparked considerable debate within the higher education community about the MOOC model's

- effect on the traditional credit and degree-based revenue model;

- ability to expand higher education's access globally and to nontraditional learners; and

- impact on faculty, pedagogy, and assessment.

The 2013 NMC Horizon Report identified MOOCs as a technology expected to enter widespread use by 2014.13 Three key factors indicate movement in that direction.

The first factor is the growing number of MOOCs, students who take them, and institutions that offer them. For example, MOOC provider Coursera began in 2012 with four institutional partners and now works with 83 educational institutions on four continents, offering approximately 400 free college-level courses to more than four million students from every country in the world.14 Harvard- and MIT-backed edX offers online courses from more than 25 edX xConsortium global member institutions, including MIT, Harvard, the University of California at Berkeley, and schools in the University of Texas system.15 The Open University has launched its own initiative, FutureLearn, with partners from 20 UK and international universities and educational entities.

The second factor is the glimmer of MOOC acceptance within the formal higher education structure. The first wave of credit- or degree-g ranting MOOCs is underway, including:

- San Jose State University's pilots to offer MOOCs for college credit16 (co-partnered with Udacity)

- Georgia Tech's MOOC-formatted Online Master's Degree of Computer Science17 (also co-partnered with Udacity)

- The American Council on Education's endorsement of five Coursera MOOCs for credit, and its evaluation of three Udacity MOOCs18

Further, MOOC-proponent MIT now includes space for students to list their MOOCs in admission applications,19 and two states — California20 and Florida21 — have passed legislation about MOOC development and use in their higher education systems.

Finally, business interest in MOOCs is growing. Instructure22 and Blackboard23 are adding a MOOC platform to their LMSs. Investors are weighing in, too, as evidenced by the influx of venture capital funding into Udacity24 and Coursera — the latter receiving $43 million in July 2013.25 MOOCs have caught the attention of Moody Investors Services, which designated them as a "credit positive" for prominent universities that offer them, but a "credit negative" for lesser-known institutions.26

But, even as MOOCs begin to gain acceptance, their original concept continues to evolve along the e-learning continuum. For example, EDUCAUSE's 2013 Sprint presented a vision in which MOOC connectivity fosters connected learning, creating an opportunity to connect the workplace, higher education, and lifelong learning. edX and Google's partnership also expands MOOC accessibility with their work on OpenEdX, an open-source learning platform, and MOOC.org, a new site for online learning that will provide a platform for institutions, businesses, and individuals around the world to produce online and blended courses.27 But, as presenters at the EDUCAUSE Sprint and others have stressed, MOOCs' ultimate place in education is still indeterminate, and any pronouncements are premature. Existing MOOCs are not the end game, and all MOOCs should be considered "beta" at this point.28

Research: Student and Institutional Perspectives

At the heart of MOOC-related activity and discussion are the actual participants themselves — that is, students and institutions whose actions and interest will bear on how MOOCs will eventually find their place in the higher education landscape. Snapshots from various research resources provide insights into current student and institutional realities and MOOC-related challenges. These resources include an EDUCAUSE membership survey on e-learning conducted for ECAR's report, The State of E-Learning in Higher Education: An Eye Toward Growth and Increased Access29; ECAR's Study of Undergraduate Students and Technology, 201330; and a search of EDUCAUSE resources and other published materials.

The Student View

MOOCs have generated considerable attention and debate among educators, legislators, investors, and the press — seemingly everyone except most undergraduate students.

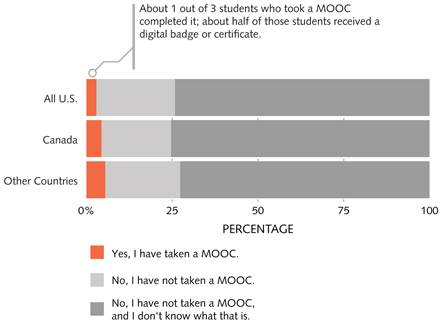

As figure 1 shows, the ECAR student and technology study found that approximately three-quarters of undergraduate students in the US (74 percent), Canada (75 percent), and other countries (73 percent) were unfamiliar with MOOCs.31 Brodeur Partners' survey of students, parents, alumni, donors, and employers reported similar awareness levels, with only 30 percent of student respondents familiar with MOOCs.32

Source: ECAR's Study of Undergraduate Students and Technology, 2013

Figure 1. Undergraduate student experiences with MOOCs

Undergraduate students registered low participation in MOOCs, too. The ECAR student and technology study reported that only a small percent have taken a MOOC, though a higher percent of Canadian (4 percent) and international (6 percent) students have taken a MOOC than their US counterparts (3 percent).33 These results are interesting when considering undergraduate students' growing adoption of online learning courses; such findings could tie back to students' unawareness of MOOCs.

The ECAR student and technology study’s focus group research suggested a disconnection between the traditional higher education path and the MOOC experience; student participants expressed little interest when asked about taking an online course offered by a premier instructor with highly polished content and 10,000, 30,000, or 100,000 other students. They were more interested in making personal connections with their instructors.34 The Brodeur Partners' survey reported a disconnection, too; students were the audience most aware of online courses in general, but they were the ones least likely to say MOOCs were a good idea (26 percent).35

Other research might help explain undergraduate student inactivity — indeed, it shows that MOOCs are most likely reaching a different audience. "Most students who have enrolled in MOOCs are internationals and/or professionals rather than enrolled college students."36 For example, the University of Edinburgh's data shows that students from 200 countries participated in the institution's MOOCs, and 70 percent of them already had an academic degree.37 A paper about the first edX MOOC concluded that, "the MOOC's students are more diverse in far more ways — in their countries of origin, the languages they speak, the prior knowledge they come to the classroom with, their age, their reasons for enrolling in the course. They do not follow the norms and rules that have governed university courses for centuries nor do they need to."38

Much has been written about MOOCs' student drop-off during courses and low completion rates:

- A Chronicle of Higher Education survey of professors who taught MOOCs reported a median of 33,000 students enrolled in their MOOCs, yet a median of only 2,600 students completed their MOOC with a passing grade.39

- The University of Edinburgh conferred "Statements of Accomplishments" to only 12 percent of its enrolled participants across its six MOOCs.40

- Coursera reported that, in 2012, roughly 5 percent of students who signed up a Coursera MOOC earned a credential signifying official completion of the course.41

- ECAR’s student and technology study noted a course completion rate of about one in three among students who took a MOOC course.42

Research from the San Jose State University/Udacity pilot offers some initial insight into the retention issue, noting that measures of student effort eclipsed all examined variables in regards to student success in its MOOC pilots.43 In addition, in an EDUCAUSE Review Online article, Coursera executives claim that MOOC students' success and retention should be considered not at the course level, but in the context of learner intent, given the varied backgrounds and motivations of students who choose to enroll.44

Considerable debate in higher education centers on how and whether students can piece together successful MOOC completions into a formal conferred degree or certificate. One current practice is to offer certificates of completions, badges, or patches to students who complete MOOCs. The ECAR student and technology study reported that about half of the students who completed a MOOC earned a digital badge or certificate.45

Like the learning experience, the notion of MOOC credentialing is still evolving. Up until now, MOOC students might have been more interested in the educational experience than in credentialing. When the University of Edinburgh surveyed its MOOC participants about their reasons for enrolling, most said it was to learn new subject matter or find out about MOOCs and online learning. Gaining a certificate or career enhancement was less significant and more localized to specific MOOCs."46

For now, it is unclear how seriously employers are taking MOOC badges, and undergraduate students themselves seem ambivalent about them. The ECAR student and technology study showed that hardly any undergraduate students — only 17 percent in the U.S., 16 percent in Canada, and 22 percent in other countries — would include a digital badge in an application portfolio.47

Institutional Perceptions

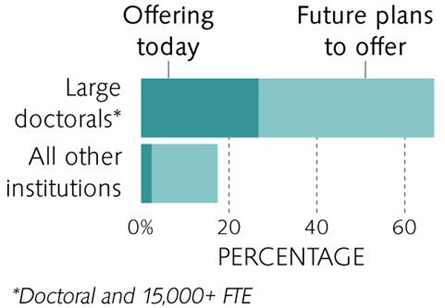

ECAR's 2013 survey of EDUCAUSE membership about e-learning shows pockets of MOOC activity, with participation centered primarily in large doctoral institutions48 (see figure 2). A Huffington Post survey of international institutions indicates greater activity in the future, with 43 percent of respondents planning to offer MOOCs by 2016.49

Source: "What MOOCs Mean to Today's Students and Institutions,"

ECAR Research Bulletin, 2013.

Figure 2. MOOC offerings and plans by institution type

ECAR's e-learning survey of EDUCAUSE members found that approximately 80 percent of respondents cited two primary reasons for offering MOOCs: to explore this new method of teaching and learning, and to build the institution's overall reputation. Attracting new students came in a distant third (less than 60 percent),50 which is interesting given that the same survey showed that respondents cited enrollment growth most frequently as an e-learning benefit.51 The Huffington Post research revealed similar sentiments. The most popular stated value of MOOCs was that they enabled respondents' institutions to keep up with developments in education (44 percent); raising the school's visibility came in second (35 percent).52

The most frequently cited reason for not offering a MOOC by ECAR's e-learning survey respondents was that it had an unclear/unproven business model.53 This finding is understandable as institutions contemplate how to recoup their potential development investments or question MOOC's financial viability given their currently free or low-cost enrollment for students. Indeed, the most recent Babson Research Group survey reported similar concerns; only 28 percent of chief academic officers believe that MOOCs are a sustainable method for offering courses.54

In the ECAR e-learning survey, no demand for MOOCs among students generated the second highest response regarding why MOOCs were not offered,55 which could again tie back to undergraduate students' relatively unfamiliarity with MOOCs — or their potential lack of interest in taking them. In the same survey, the third most common reason for not offering MOOCs was a lack of leaders’ interest in them.

The 2013 Inside Higher Ed surveys of presidents and provosts noted similar uncertainty about MOOCs: only 14 percent of presidents strongly agreed — and another 28 percent agreed — that MOOCs have "great potential to make a positive impact."56 The publication's survey of provosts found them almost equally divided about whether MOOCs will have a positive impact, and they expressed concern about a possible impact on their business models.57

This lack of senior administrative support for MOOCs is noteworthy given the previously discussed belief among academic leaders that online learning is critical to the long-term strategic mission of their institutions. Administrative disinterest in MOOCs could represent a significant barrier to institutional adoption, especially since ECAR research repeatedly shows the importance of senior leadership support and involvement in successful technological initiatives.

Implications and Resources

What goes around comes around. Much like e-learning 10 years ago, MOOCs represent a new educational gateway — but exactly how MOOCs will impact colleges and universities remains uncertain. The potential is considerable, from online learning to open learning to perhaps even massive learning and an age of connected learning.58 The impediments, however, are equally significant:

- Proven tactics in areas such as credentialing are still elusive.

- Financial and ROI concerns promote caution.

- The traditional undergraduate student base's uncertain interest — and the relative disinterest of institutional leadership — complicate planning, too.

Until now, many EDUCAUSE member institutions have adopted a "wait and see" strategy on whether or how to offer MOOCs, especially as today's MOOCs begin to morph as experiences, research, and proven practices emerge. As with online learning, the clarity that eventually emerges from knowledge will help leadership astutely evaluate MOOCs' strategic value to their institution's long-term mission. For example, directing MOOCs' connectivity could help institutions create strategically beneficial engagement and collaboration both with new audiences, such as by using introductory curriculum to generate relationships between faculty, flagship programs, and potential students59; and with alumni,60 such as by fostering lifelong learning through refresher MOOCs.61

As table 1 shows, numerous resources exist to help institutional leadership understand MOOCs' evolution and implications. The experiences of early adopters, including Harvard, MIT, Georgia Tech, and San Jose State University, help point the way for others. Forums such as the EDUCAUSE Sprint 2013: "Beyond MOOCs: Is IT Creating a New, Connected Age?"62 offer opportunities to learn and engage others about MOOCs. Finally, the MOOC Research Initiative’s research hub, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, will offer additional MOOC-related research.

Table 1. MOOC Resources

|

Resource |

Resource |

Content |

|---|---|---|

|

EDUCAUSE Sprint 2013: Beyond MOOCs: Is IT Creating a New, Connected Age? |

EDUCAUSE |

Webinars and other online resources re: MOOCs' technological, pedagogical, and broader implications |

|

EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research |

Research bulletin summarizing ECAR's recent MOOC-related research |

|

|

EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research |

MOOC-related findings and recommendations from annual student technology survey |

|

|

MOOC Planning: 50 Plus Questions to Answer [https://docs.google.com/document/d/1QjEcIxCymm_0qTHC8aL6ziEqr14MnV46gpHu82mC6LY/] |

EDUCAUSE CIO Discussion List |

Google Doc compilation of MOOC-related questions for institutional discussion |

|

EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative |

Overview of MOOC technology and practices |

|

|

EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative |

Summary of ELI's online focus session about MOOCs |

|

|

Stephen Downes and George Siemens |

Blog about MOOC news and developments |

|

|

Robert McGuire |

Blog about MOOC news and developments |

|

|

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Athabasca University |

Research initiative re: MOOC's impact on education |

Ultimately, a key to MOOCs' institutional success is for leaders to act knowingly and deliberately, and in support of the institutional mission — in other words, to look before leaping.

- Tuesday Recap, "Key Takeaways," EDUCAUSE Sprint 13, "Beyond MOOCs: Is IT Creating a New, Connected Age?" July 30, 2013.

- Paul Arabasz, Judith A. Pirani, and Dave Fawcett, Supporting E-Learning in Higher Education, EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, 2003.

- The report defined "e-learning" as technology in education and examined activity and support requirements for online distance learning courses, traditional courses supplemented with technology, and hybrid courses. It used the umbrella term "e-learning course" to refer to all three course types.

- Arabasz, Pirani, and Fawcett, Supporting E-Learning, 2003, p. 9.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- ECAR Annual Study of Students and IT, EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research.

- "2012 Students and Technology," Infographic, EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, 2012.

- "Students and Technology, 2013," Infographic, EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, 2013.

- Jacqueline Bichsel, The State of E-Learning in Higher Education: An Eye Toward Growth and Increased Access, EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, 2013, p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 6.

- Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), EDUCAUSE Library.

- New Media Consortium, NMC Horizon Report: 2013 Higher Education Edition, 2013, p. 11.

- Tamar Lewin, "Coursera, an Online Education Company, Raises Another $43 Million," The New York Times, July 10, 2013.

- "edX Expands xConsortium to Asia and Doubles in Size with Addition of 15 New Global Institutions," Press Release, edX, May 21, 2013.

- Pat Lopes Harris, "SJSU and Udacity Partnership," SJSU Today, San Jose State University, January 15, 2013.

- Jason Maderer, "Georgia Tech Announces Massive Online Master's Degree in Computer Science," Georgia Tech News Room, Georgia Tech, May 14, 2013.

- Steve Kolowich, "American Council on Education Recommends 5 MOOCs for Credit,” Chronicle of Higher Education, February 7, 2013.

- Laura Pappano, "The Rise of MOOCs," 6th Floor Blogs, New York Times, September 16, 2013.

- Leila Mayer, "California Bill Allowing Credit for MOOCs Passes Senate," Campus Technology, June 6, 2013.

- Ry Rivard, "'Watered Down' MOOC Bill Becomes Law in Florida," Inside Higher Ed, July 1, 2013.

- Joshua Kim, "Open Online Education and the Canvas Network," Blog U, Inside Higher Ed, November 1, 2012.

- Jeffrey R. Young, "Blackboard Announce New MOOC Platform," The Chronicle of Higher Education, July 10, 2013.

- Ari Levy, "Udacity Raises $15 Million as Money Pours into Online Education," Bloomberg Tech Deals, October 25, 2012.

- Lewin, "Coursera."

- Sara Grossman, "Moody Says MOOCs Could Raise a University's Credit Rating," Chronicle of Higher Education, June 24, 2012.

- Dan O'Connell, "EdX Announces Partnership with Google to Expand Open Source Platform," Press Release, MOOC.org, September 10, 2013.

- Gregory Dobbin, "EDUCAUSE Sprint 2013, Day 1: Of Higher Education and Gateways," EDUCAUSE, July 18, 2013.

- For The State of E-Learning in Higher Education: An Eye Toward Growth and Increased Access, EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research received survey responses from 311 member institutions.

- For ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2013, ECAR collaborated with 251 institutions to collect responses from more than 113,000 students worldwide about their technology experiences.

- Eden Dahlstrom, J. D.Walker, and Charles Dziuban, ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students, 2013, EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, 2013,p. 18.

- "Study Suggests Careful Navigation in Move Towards Massive Open Online Courses," Press Release, Brodeur Partners, June 26, 2013.

- Dahlstrom, Walker, and Dziuban, ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students, p. 18.

- Ibid., p. 19.

- "Study Suggests Careful Navigation," 2013.

- EDUCAUSE Executive Briefing, "What Campus Leaders Should Know about MOOCs," EDUCAUSE, 2012, p. 2.

- Sara Custer, "The University of Edinburgh Releases First MOOC Data," The PIE News, June 12, 2013. For complete report see, MOOCs@Edinburg Group, MOOCs @ Edinburgh 2013, Report 1, May 10, 2013.

- Jake New, "Study: Nearly 9 in 10 MOOC Participants Were Male," eCampus News, June 7, 2013.

- Steven Kolowich and Jonah Newman, "Additional Results from the Chronicle Survey," Chronicle of Higher Education, March 18, 2013.

- MOOCs Group, MOOCs @ Edinburgh, p. 2.

- Daphne Koller, Andrew Ng, Chuong Do, and Zhenghao Chen, "Retention and Intention in Massive Open Online Courses: In Depth," EDUCAUSE Review Online, June 3, 2013.

- Dahlstrom, Walker, and Dziuban, ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students, p. 18.

- Carl Straumsheim, "The Full Report on Udacity Experiment," Inside Higher Ed, September 12, 2013.

- Koller, Ng, Do, and Chen, "Retention and Intention."

- Dahlstrom, Walker, and Dziuban, ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students, p. 18.

- MOOCs Group, MOOCs @ Edinburgh, p. 2.

- Dahlstrom, Walker, and Dziuban, ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students, p. 20.

- Susan Grajek, Jacqueline Bischsel, and Eden Dahlstrom, "What MOOCs Mean to Today's Students and Institutions," EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, 2013, p. 1.

- Vala Ashfar, "Adoption of Massive Online Courses [Worldwide Survey]," Huffington Post, May 20, 2013.

- Grajek, Bischel, and Dahlstrom, “What MOOCs Mean,” p. 1.

- Bichsel, The State of E-Learning in Higher Education, p. 8.

- Ashfar, "Adoption of Massive Online Courses," 2013.

- Grajek, Bischsel, and Dahlstrom, "What MOOCs Mean," p. 1.

- James G. Mazoue, "The MOOC Model: Challenging Traditional Education," EDUCAUSE Review Online, January 28, 2013.

- Grajek, Bischsel, and Dahlstrom, "What MOOCs Mean," p. 1.

- Doug Lederman, "Affirmative Action, Innovation, and the Financial Future: A Survey of Presidents," Inside Higher Ed, March 1, 2013.

- Scott Jaschik, "Skepticism about Tenure, MOOCs, and the Presidency," Inside Higher Ed, January 23, 2013.

- Dobbin, "Of Higher Education and Gateways," 2013.

- W. Joseph King and Michael Nanfito, "To MOOC or Not to MOOC?" Inside Higher Ed, November 29, 2012.

- Ibid.

- Allan Gyorke, "MOOCs and Beyond: Video of the Day," EDUCAUSE Sprint 2013: "Beyond MOOCs: Is IT Creating a New, Connected Age?" July 30, 2103.

- EDUCAUSE Sprint 2013: "Beyond MOOCs: Is IT Creating a New, Connected Age?" EDUCAUSE, 2013.

Sidebar 1: MOOC Backgrounder

To varying degrees, a MOOC is truly massive; theoretically, it has no enrollment limits and anyone can participate (usually at no cost) online. A MOOC's learning activities typically take place over the web, structured around a set of learning goals in a defined area of study.1

Recent media coverage might lead one to believe that MOOCs are a relatively new phenomenon, but their roots are actually several years old. Canadian educators George Siemens and Stephen Downes pioneered MOOCs in 2008. Their vision (sometimes characterized as cMOOCs) was one of "ecosystems of connectivism — a pedagogy in which knowledge is not a destination but an ongoing activity, fueled by the relationships people build and the deep discussions catalyzed within the MOOC. The model emphasizes knowledge production over consumption, and new knowledge generated helps to sustain and evolve the MOOC environment."2

In 2012, another version of MOOCS emerged (sometimes called xMOOCs), involving multiple-week courses featuring short lecture video clips paired with rapid-recall multiple choice questions, plus some form of exams, papers, and project assignments, and a small amount of reading.3 Course materials are located in a central repository, and automated software is sometimes used to assess student performance.4 These courses can draw tens, even hundreds of thousands of students from around the world. They attain large scale by reducing instructor contact; students often rely on self-organized study and discussion groups.5

Over the past 18 months, higher institutions from around the world have begun to offer their own homegrown MOOCs and xMOOCs from entities such as edX, founded by Harvard University and MIT, and Coursera and Udacity, which have Stanford University roots. Currently, institutions typically offer MOOCs free of charge and students usually receive no college credit for course completion. Some MOOCs have hit new course enrollment levels, in a few cases attracting more than a hundred thousand students from around the world.

- "7 Things You Should Know about MOOCs II," EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, 2013, p. 1.

- New Media Consortium, NMC Horizon Report: 2013 Higher Education Edition, 2013, p. 11.

- Anya Kamenetz, "Can We Move Beyond the MOOC to Reclaim Open Learning?" Huffington Post, June 16, 2013.

- New Media Consortium, Horizon Report, p. 12.

- EDUCAUSE Executive Briefing, "What Campus Leaders Should Know about MOOCs," EDUCAUSE, 2012, p. 1.

© 2013 Judith A. Pirani. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.