Key Takeaways

- A university-wide survey on students' mobile learning practices showed that ownership of mobile devices is high among students and that tablets are the most popular devices for academic purposes.

- The survey also found that mobile learning typically occurs outside the classroom, with only limited guidance from instructors.

- To improve mobile learning effectiveness, students and instructors need help adopting more effective learning and teaching practices across content areas.

Mobile technologies are playing an increasingly important role in college students' academic lives. Devices such as smartphones, tablets, and e-book readers connect users to the world instantly, heightening access to information and enabling interactivity with others. Applications that run on these devices let users not only consume but also discover and produce content.1 As such, they continue to transform how college students learn, as well as influence their learning preferences, both within and outside the classroom.

The popularity of mobile technologies among college students is increasing dramatically. Results from the ECAR research study on students suggest that many undergraduate students bring their own digital devices to college, favoring small and portable ones such as smartphones and tablets. 2 Although students still rate laptops (85 percent) as the most important devices to their academic success, the importance of mobile devices such as tablets (45 percent), smartphones (37 percent), and e-book readers (31 percent) is noticeably on the rise. Increasingly, students say they want the ability to access academic resources on their mobile devices.3 In fact, 67 percent of students' smartphones and tablets are reportedly being used for academic purposes, a rate that has nearly doubled in just one year.4

Convenience, flexibility, engagement, and interactivity are all factors that make mobile learning more attractive to students.5 With these trends in mind, it is not surprising the New Media Consortium's 2013 Horizon Report6 predicted that mobile applications and tablet computing will have a time-to-adoption of one year or less in higher education. Many universities now use mobile technologies and create mobile-optimized versions of their websites or build stand-alone applications that can be downloaded from mobile application stores.7

To successfully adopt mobile technologies across the university, however, we need more information about the student population's mobile access and use. Here, we share the results of a campus-wide survey at the University of Central Florida (UCF) about ownership and use of mobile technologies among college students. We focused our study on students' access and use of mobile technologies, paying particular attention to their use of mobile devices and applications, their learning practices, and their demographic characteristics. Our research sought to answer the following questions:

- What mobile devices do college students have for accessing and engaging with digital content? Do demographic factors influence this access?

- How do college students use mobile technologies (devices and apps) for academic purposes? What demographic factors influence this use?

Our goal was to provide a baseline of mobile technology ownership and usage on which to build future research. We expect that the results will guide potential initiatives to help students and instructors in adopting more effective learning and teaching practices across content areas. We specifically address the implications for student training and skill development and for instructor support.

Key Issues

Although some research exists on mobile technology use in higher education, many factors influencing this use have yet to be fully explored.

Multiple devices are available to and owned by students, which can complicate issues such as the design of training and provision of support. Although many students own mobile devices, ownership is not universal. Identifying specific student demographics that might relate to ownership trends is thus critical. It is also important to determine which devices are most helpful for academic use; mobile technologies afford new opportunities for learning, but their use does not guarantee that effective learning will take place.

Effective use of mobile technologies requires that students exhibit digital literacy skills such as being able to access, manage, and evaluate digital resources.8 Further, students might be informally using many different applications for academic purposes, making it difficult to determine what they use and how.

Research has shown that having a clearer understanding of students' mobile practices encourages the university to implement more student-centered support and services.9 Technical training and skill development emerge as important factors, and students perceive both as more important than the technology itself.10

These issues of student access and use of mobile technologies also have implications for instructor development. Although students expect instructors to use technology to engage them in the learning process, only a little over half (54 percent) of U.S. students said their instructors provided training for technology used in their courses.11 Instructors generally are unprepared to integrate mobile technologies in learning, as most faculty professional development opportunities do not specifically focus on it. Also, because student performance is usually assessed by finished products, it is difficult to ascertain if using technology contributes to or limits students' engagement and learning. Finally, technology use is further influenced by the modality of courses in which it is used. Understanding students' mobile practices more deeply can guide informed instructor development in the future.

Because the technology is moving at a faster pace than research, mobile learning research is still in the relatively early stages,12 with mobile phones and PDAs the most studied devices.13 The implications of newer mobile technologies — such as tablets and e-book readers — on learning are less discussed.

Mobile learning often takes place outside a formal learning environment, and it tends to become personalized via users' personal mobile devices. As a result, one major challenge for mobile research is capturing data on user demographics and usage of specific mobile devices. Moreover, previous studies focused mainly on investigating student motivations, perceptions, and attitudes toward mobile learning,14 but few focused on mobile learning practices and strategies.15 Although mobile learning support is rare in classroom settings, research on faculty support regarding how mobile technologies can be used for teaching is even scarcer. Therefore, more research is needed for mobile teaching and learning strategies and how these strategies are implemented to engage learning.16

Methods

Because of the sparse research on students' mobile learning practices, we developed a survey questionnaire. This survey explores basic access and use of mobile devices, and identifies preliminary barriers to the integration of mobile technologies on the college campus. The survey was approved by UCF's Institutional Review Board and tested by survey experts for content validity. The survey questionnaire includes both closed and open-ended questions based on previously distributed surveys available online17 and surveys previously distributed by the university.

We collected data (N = 1,082) in summer 2012. Participants were undergraduate (N = 809) and graduate (N = 133) students at UCF. The participants surveyed were in 84 courses (in face-to-face, blended, and fully online courses) from 12 different colleges at the university. The sample was 69 percent female, 60 percent Caucasian, and between the ages of 18 and 63 (M = 26; SD = 8.17). In addition to the student survey, we slightly changed the wording of the questions and recruited 16 course instructors to complete the survey as well.

Survey Results

Students' general device ownership of mobile technology and how they use the technology for academic purposes is explored next.

General Device Ownership

Question: What mobile devices do college students have for accessing and engaging with digital content? Are there demographic factors that influence access?

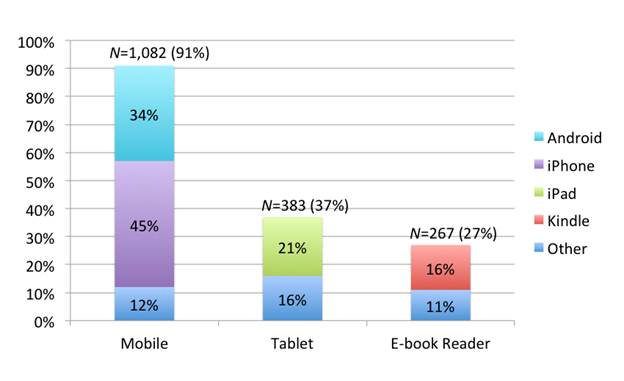

Descriptive analyses regarding student access showed that more than 91 percent of respondents (N = 849) owned a small mobile device (such as an iPhone, Android, or iPod Touch). However, only 37 percent (N = 290) owned a mobile tablet (such as iPad, Android tablet, or Kindle Fire) and 27 percent (N = 186) owned an e-book reader (such as Kindle or NOOK). Figure 1 shows a detailed breakdown of device ownership.

Figure 1. Device ownership (N = 1,082)

Ownership of small mobile devices was prevalent among students regardless of demographic factors. However, academic standing and age emerged as having an impact on tablet ownership. Graduate students tended to own tablet devices more than undergraduate students (X2(3, N = 943) = 8.68, p = .03). Age also had a small but significant impact on tablet ownership (r(932) = 0.095, p < .01), with older students tending to own tablet devices more than younger students.

The factors that significantly affect students' access to e-book readers included their current GPA (X2(4, N = 939) = 13.07, p = .01) and gender (X2(2, N = 934) = 12.18, p < .01). Students with higher GPAs tended to have more access to e-book readers than those with lower GPAs, and female students tended to have more access than male students.

Device Use for Academic Purpose

Question: How do college students use mobile technologies (devices and apps) for academic purposes? Are there demographic factors that influence this use?

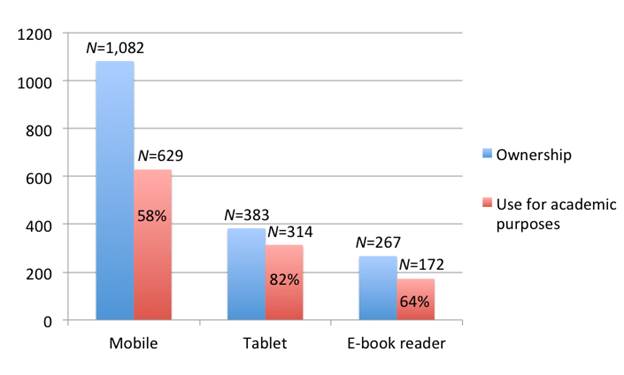

Our results indicated that, among the students who had access to mobile devices, more than half reported that they used them for academic purposes. This was especially true if they owned a tablet device. As figure 2 shows, 82 percent of tablet device owners said they used the device for academic purposes, while only 58 percent of small mobile device owners and 64 percent of e-book reader owners reported doing so.

Figure 2. Comparing ownership and use for academic purposes (N = 1,082)

The students' academic year, ethnicity, gender, age, and GPA significantly affected their use of small mobile devices and e-book readers for academic purposes. In particular:

- Freshmen and sophomores tended to use small mobile devices in courses more often than juniors and seniors (X2(15, N = 803) = 29.30, p = .01).

- Students identifying as Asian tended to use these devices to complete assignments more often than other groups (X2(25, N = 900) = 51.69, p < .01).

- Males tended to use these devices for academic purposes more than females (X2(5, N = 926) = 14.16, p = .01).

- Age also had a small but significant impact on the academic use of small mobile devices (r(924) = 0.092, p < .01).

- Because tablet use for academic purposes was high, no demographic factor emerged as significant.

One of the most interesting results we found was a negative relationship between students' GPA and academic use of their small mobile devices and e-book readers. Students with lower GPAs tended to use their small mobile devices for academic purposes more frequently than those with higher GPAs (r(931) = -0.073, p = .03). The same was true with the relationship between GPA and academic use of e-book readers (r(917) = -0.088, p < .01).

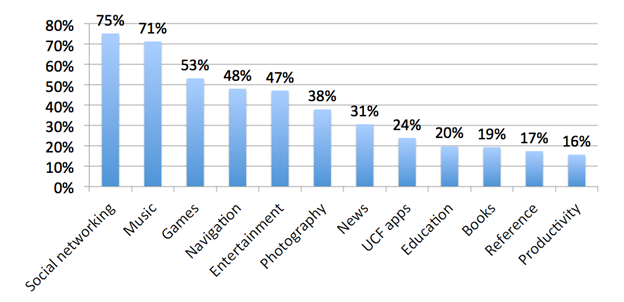

A primary goal of our survey was to better understand how students used mobile apps within and outside the formal learning context. To address this, we asked students what categories of apps they used most frequently. Not surprisingly, as figure 3 shows, students reported using mobile apps most frequently, such as for checking social networking sites, listening to music, and playing games. The academic apps that they reported using most included university apps (UCFMobile, Tegrity, Mobile Learn [https://help.blackboard.com/Mobile_Learn], and so on) and apps for education (Flash Cards, Khan Academy, iTunes U, and so on); books (such as CourseSmart and Inkling), references (Dictionary, Wikipanion, WolframAlpha, and so on); and productivity (such as Evernote, Dropbox, Pages, Keynote, and Notes). In addition to these categories, in an open-ended question students said they frequently used apps (such as Google and Safari) for information searching.

Figure 3. Most popular app categories rated by students (N = 933)

In the instructor version of the survey, we asked instructors if they have ever encouraged their students to use mobile apps to complete an assignment. Only three of 16 instructors answered yes, yet 52 percent of our student respondents who owned a mobile device said that they used them on their own to complete an assignment at least once a week. Moreover, students said they would like to see more instructors use mobile apps and devices in coursework. Of the 16 instructors surveyed, 10 indicated that they were interested in adopting mobile apps in the future. The major concerns they had were related to student access and technical support for students and for themselves. These findings indicate a gap between instructor use of mobile technologies in teaching and student demand for integrating these technologies for learning.

Discussion

Our results yield two main insights that might be beneficial for promoting mobile learning.

Facilitating Learning

The survey results suggest that the type of device makes a difference for academic use. The findings are consistent with the findings of the ECAR study in that tablets emerge as a potentially powerful mobile device in academia.18 Although tablet ownership was only 37 percent — and much lower than for smaller mobile devices — we found that owning a tablet seems to be beneficial for college learners. Of those who owned tablets, 82 percent used them for academic purposes (as opposed to 58 percent for small mobile devices), and academic use was universal regardless of demographic factors. Tablets emerge as powerful learning devices because they are small and portable (and thus easy to bring to campus), while the screen size lets students retrieve and compose information more easily than small mobile devices.

Given these findings, students — particularly younger and undergraduate students — need more access to tablets. For example, our university library loans them to students, but the number available and checkout time allowed is limited. In addition to increasing such lending opportunities, schools could work with companies to offer tablets to students at a reduced price, for example. Accessing the device is the first step in supporting and increasing students' mobile learning practices.

Our survey results also indicate that students still need support in how to use mobile technologies for learning. In particular, students with lower GPAs reported using mobile devices, for academic purposes more frequently than higher performers. Similar trends were observed with the academic use of other emerging technologies, such as social media; Facebook users had significantly lower GPAs than non-users.19

Although our survey results do not infer a direct causal relationship between mobile device use and student learning, educators and researchers must figure out why innovative technologies do not fulfill the promise of enhancing teaching and learning. We also see a need to promote digital literacy curriculum or training among college students to help them adopt knowledge and learning practices and engage them with digital media for learning. In particular, this negative relationship between mobile use and learning calls for support for low-achieving students to help them use information effectively and efficiently via mobile technologies and to encourage them not just to become technologically literate but also to use these technologies to improve their learning motivation and performance.

Integrating Technologies into the Curriculum

There is a gap between students owning mobile devices and actually using them for academic purposes. Our survey results showed that 58 percent of small mobile device owners, 64 percent of e-book reader owners, and 82 percent of tablet device owners reportedly use these devices for academic purposes. How can we help to fill that gap?

One opportunity here is to facilitate specialized professional development to help instructors learn and integrate mobile technologies into the curriculum. In the survey, students reported that the academic apps that they used most frequently were information apps (Google, Safari), reference apps (Dictionary), school apps (UCF Mobile, Mobile Learn), and resource management apps (Dropbox, Evernote, Notes, word processing). We suggest that, as a starting point, institutions compile a list of these familiar and frequently used academic apps for instructors and help them incorporate these apps into their courses.

When integrating an app in the curriculum, instructors should consider relevant technical limitations and poll their students to see what devices they own. For example, most students own either an Android or iPhone device, so instructors should make sure that any academic app works on both systems. In addition, 9 percent of our respondents indicated that they do not own a mobile device. If an instructor requires the use of a mobile app in a class, he or she must inform students of this requirement at the beginning and provide university resources or other options for students who lack access a device.

In addition to technical aspects, instructors should consider using sound pedagogical practices to support their mobile learning activities. These activities should be designed to support a meaningful learning purpose, such as sharing current events and resources via Twitter and using polls conducted via text message to engage students in large classes. Integrating mobile technologies in the curriculum could start with designing an assignment. Instructional designers can help instructors deliver professional development training on innovative technologies and work with them individually to incorporate mobile technologies into learning.

Conclusion

Mobile learning in U.S. higher education is on the rise. College students use their mobile devices mostly for self-directed informal learning rather than in the formal academic context, however, which makes it challenging to get an accurate picture of academic use. In this study, we collected data about ownership of mobile devices among students using a diverse sample from a large university. We also explored students' learning practices with mobile technologies and focused on the interactions among technologies, contents, and pedagogies. The results indicate that learners need more access to academic-friendly devices, such as tablets, and additional support to integrate mobile technologies for learning. The findings also help clarify future directions of faculty development. Instructors must gain knowledge of these innovative technologies and integrate them into the curriculum with sound facilitation and assessment strategies, as well as be able to support the mobile practices of students.

This survey research has its limitations; the sample included undergraduate and graduate students at only one university in the U.S. Future research could focus on varied contexts or samples, such as adults or students of other ages, regions, or countries. Also, while the survey provides data regarding mobile usage, it does not speak to the effectiveness of this instructional delivery method. Further experimental research could be designed and conducted to measure the effectiveness of mobile learning in various disciplines.

Our survey's purpose is to provide baseline information and develop potential action items. Based on the survey results, we have three primary future plans at UCF.

- First, we plan to promote opportunities to increase student access to mobile tablet devices, such as through increased library loans and campus discount programs from manufacturers.

- Second, we plan to establish a faculty focus group for mobile learning to further discuss how innovative instructors are using these technologies in the classroom settings.

- Finally, we plan to create faculty development opportunities, particularly on the topic of mobile learning. Examples here include designing technical or logistical job aids, delivering periodic face-to-face and webcast events, and offering one-on-one consultations to help instructors devise class- or assignment-specific strategies in a pedagogically sound and meaningful way.

Further research in this field will help guide other initiatives to encourage effective use of mobile devices in teaching and learning. We hope that our survey results will encourage such research.

- Eden Dahlstrom, ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, 2012.

- Ibid, p. 14.

- Ibid, p. 16.

- Ibid, p. 14.

- Ryan Seilhamer, Baiyun Chen, and Amy Sugar, "A Framework for Implementing Mobile Technology," in Handbook of Mobile Learning, Z. Zane Berge and Lin Muilenburg, eds. (Routledge, 2013), pp. 382–394.

- Larry Johnson, Samantha Adams Becker, M. Cummins, V. Estrada, A. Freeman, and Holly Ludgate, NMC Horizon Report: 2013 Higher Education Edition, New Media Consortium, 2013.

- 2009-10 Mobile Learning Report [http://blogs.creighton.edu/ccasipad/files/2012/07/ACU2009-10MobileLearningReport.pdf], Abilene Christian University, 2011 (right column on web page); Kyle Bowen and Matthew Pistilli, Student Preferences for Mobile App Usage, EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research, 2012; Brian Rellinger, "Impact of Mobile Devices on Universities," 2011; and Dian Schaffhauser, "A Mobile Education: Student-Created Apps," Campus Technology, vol. 24, no. 5 (2011), pp. 28–32.

- Helen Drenoyianni, Lampros Stergioulas, and Valentina Dagiene, "The Pedagogical Challenge of Digital Literacy: Reconsidering the Concept — Envisioning the "Curriculum" – Reconstructing the School," International Journal of Social and Humanistic Computing, vol. 1, no. 1 (2008), pp. 53–66.

- Bowen and Pistilli, "Student Preferences," p. 11.

- Dahlstrom, ECAR Study, p. 22.

- Ibid., p. 22.

- Gwo-Jen Hwang and Chin-Chung Tsai, "Research Trends in Mobile and Ubiquitous Learning: A Review of Publications in Selected Journals from 2001 to 2010," British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 42, no. 4 (2011), pp. E65–E70.

- Wen-Hsiung Wu, Yen-Chun Jim Wu, Chun-Yu Chen, Hao-Yun Kao, Che-Hung Lin, and Sih-Han Huang, "Review of Trends from Mobile Learning Studies: A Meta-Analysis," Computers & Education, vol. 59, no. 2 (2012), pp. 817–827.

- Hwang and Tsai, "Research Trends in Mobile and Ubiquitous Learning," pp. E65–E70.

- Jui-Long Hung and Ke Zhang, "Examining Mobile Learning Trends 2003-2008: A Categorical Meta-Trend Analysis Using Text Mining Techniques," Journal of Computing in Higher Education, vol. 24, no. 1 (2012), pp. 1–17; RuoLang Wang, Rolf Wiesemes, and Cathy Gibbons, "Developing Digital Fluency through Ubiquitous Mobile Devices: Findings from a Small-Scale Study," Computers & Education, vol. 58, no. 1 (2012), pp. 570–578; and Wu et al., "Review of Trends," pp. 817–827.

- Hung and Zhang, "Examining Mobile Learning Trends," pp. 1–17

- Alan Dennis, Thomas Duffy, and Anastasia Morrone, Indiana University e-Textbook Project: Spring 2010 Finding, Indiana University, 2010; and Alan Dennis, e-Textbooks at Indiana University: A Summary of Two Years of Research [https://assets.uits.iu.edu/pdf/eText%20Pilot%20Data%202010-2011.pdf], Indiana University, 2011.

- Dahlstrom, ECAR Study, p. 25.

- Paul A. Kirschner and Ayrn C. Karpinski, "Face-book and Academic Performance," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 26, no. 6 (2010), pp. 1237–1245.

© 2013 Baiyun Chen and Aimee deNoyelles. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 license.