Key Takeaways

- To plan for future mobile learning two military educational schools conducted a study of current mobile device ownership and use by their students.

- Survey results show that a majority of students say they would use mobile learning if it were available, with a higher fraction of students interested in mobile learning the younger the student body, which suggests demand for mobile learning will continue to grow in the future.

- The results seem to align with general higher education institutions, with younger students showing increasing use of mobile devices and interest in accessing online learning materials.

- Besides e-mail and web browsing on their mobile devices, students want to be able to access course management systems; sync course calendars across their devices; access course reading materials; and use mobile applications that support class work and provide remote access to class lectures.

The use of mobile electronic devices such as smartphones, e-readers, and tablet computers is exploding, and students today are more connected than ever. StatCounter GlobalStats reports "Global internet usage through mobile devices, not including tablets, has almost doubled to 8.5% in January 2012 from 4.3% last year." A 2011 infographic in the blog digitalbuzz predicts that "[b]y 2014, mobile Internet should overtake desktop Internet usage." The 2011 New Horizon Report, sponsored by The New Media Consortium and the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, predicts that by 2015 people using mobile devices will make up 80 percent of those accessing the Internet. "More important for education, Internet-capable mobile devices will outnumber computers within the next year."1 In fact, some countries such as Korea, Japan, Sweden, and Australia have already surpassed these milestones with more than 80 mobile broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants in 2011.2 Furthermore, in Japan "over 75% of Internet users already use a mobile as their first choice for access."3

As described in The 2011 New Horizon Report, "People expect to be able to work, learn, and study whenever and wherever they want. ... Mobiles contribute to this trend, where increased availability of the Internet feeds the expectation of access. Feelings of frustration are common when it is not available..."4 This paradigm shift in how people, particularly younger people, connect and interact with the Internet is fueled by the

- development of an increasing variety of Internet-capable mobile devices,

- expansion of networks that support connectivity, and

- increasing focus by web content providers on creating flexible web content that is accessible via mobile devices.

Anyone who has been in the classroom recently has probably observed this trend firsthand, with increasing numbers of students using smartphones and personal digital assistants in place of laptop and desktop computers.

In the research reported here, we assessed these trends via a survey of undergraduate and graduate students at two United States military educational institutions: the United States Naval Academy (USNA) and the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS). While unique in some ways, these students are similar in many ways to postsecondary and graduate students throughout the United States. Our primary goal was to better understand which mobile devices should be targeted for current and future instructional media development. Via our survey, we addressed the following questions:

- What are the trends in mobile device usage by today's students?

- Which types of course content do current students prefer for their mobile devices and in what format?

- What will future university students expect schools to provide on their mobile electronic devices?

Background

The surveys were conducted on behalf of the NPS Center for Educational Design, Development, and Distribution (CED3). CED3 is a subunit of NPS Academic Affairs and supports the NPS mission in the two broad areas of development and distribution of NPS educational materials for both resident and distance learning courses. CED3's responsibilities include the creation and delivery of university-level educational products for NPS, research into new educational technologies, and facilitation of NPS faculty's use of new technology.

Since CED3 promotes maintaining high-quality material, it wanted to provide guidance to its developers regarding the devices students would be using. CED3 presumed that NPS students want to have information and educational products available on demand, anywhere, and at any time ("mobile learning"), and that technology will be available to support the on-demand nature of future education. As part of its due diligence CED3 did a general literature search to discover the devices students at other institutions and the general public are using, and requested surveys of NPS and USNA students to determine what mobile devices they are using.

The United States Naval Academy and the Naval Postgraduate School

The United States Naval Academy was founded in 1845. Today it is an accredited undergraduate institution with a student body of approximately 4,500 midshipmen. Located in Annapolis, Maryland, the Naval Academy offers a four-year undergraduate curriculum leading to a Bachelor of Science degree. In so doing, it blends required and elective courses similar to those offered at leading civilian colleges with professional subjects. As described on the USNA website, the curriculum consists of three basic elements:

- Core requirements in engineering, natural sciences, the humanities, and social sciences to ensure that graduates can think critically, solve increasingly technical problems in a dynamic, global environment, and express conclusions clearly.

- Core academic courses and practical training to teach the leadership and professional skills required of Navy and Marine Corps officers.

- An academic major that permits a midshipman to explore a discipline in some depth and prepare for graduate level work.

The Naval Postgraduate School was originally established at Annapolis in the early 1900s as a postgraduate school of marine engineering with courses of study in ordnance and gunnery, electrical engineering, radiotelegraphy, naval construction, civil engineering, and marine engineering. In December 1951 the school was moved across country to its current campus in Monterey, California.

Today NPS is a postgraduate academic institution whose student body consists predominantly of officers from the five U.S. uniformed military services, military officers from approximately 30 other countries, and Department of Defense civilian employees. Most of the 2,601 students — of which 1,831 are in residence and 770 participate in various distance learning curricula — pursue a master's degree in programs that run year-round and take from 18 months to two years to complete.

The median age of a USNA undergraduate is approximately 20 years, the median age of an NPS resident student is about 30 years, and the median age of an NPS distance-learning student is approximately 35 years. We do not know how representative USNA students are of the general undergraduate student population in the United States, nor do we know how representative NPS graduate students are of the general graduate student population. They clearly differ in a number of dimensions, particularly the military environment in which they work and go to school, though it is not clear whether those differences are relevant to the survey topic of mobile learning. In any case, what is relevant to CED3 is that the current NPS students are precisely the constituency they currently serve, and the USNA undergraduates are representative of future NPS students (in roughly five to 10 years).

Related Literature

What devices do students own?

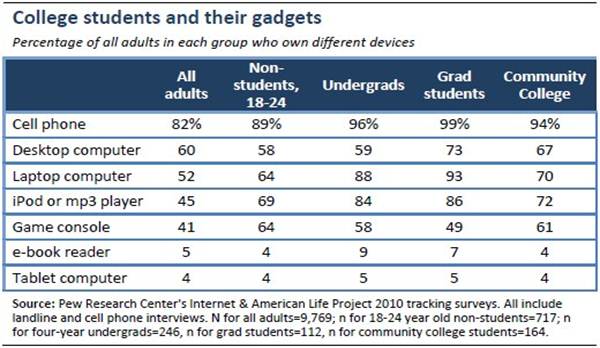

The accompanying chart from the 2010 Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project report "College Students and Technology"5 shows over 90 percent cellphone ownership for college students.

In "An Investigation into Student Mobile Devices: Evaluating the Potential for Mobile Learning," the authors report the results of a 2010 survey of City University, London, students. They found that "… amongst the 816 responses received there were 853 different mobile phones (with some students owning more than one type of mobile phone), and of these 597 were Smartphones (including Androids, Blackberries, iPhones and Nokia / Symbian devices." They concluded: "Mobile learning projects that centre on students using their mobile devices for receiving and viewing information around teaching should be explored. Students seem happy to use their devices for teaching-related activities or delivery of learning content, but not for interacting in class."6

The study "Examining Mobile Technology in Higher Education: Handheld Devices In and Out of the Classroom," which focused on the BlackBerry as a learning tool, found:

"… as a learning tool, participants viewed the BlackBerry® in a marginally positive way, rating it as just somewhat effective and slightly more positively than negatively as an instructional tool. When participants used the BlackBerry® to learn, clearly, communication for the intent of organizing or sharing information with other students served as the key learning advantage associated with the devices. It was also the case that a small proportion of students did not find the technology useful which may be indicative of their perceptions of limitations in how the technology was used in their classrooms …"7

What do students use mobile devices for?

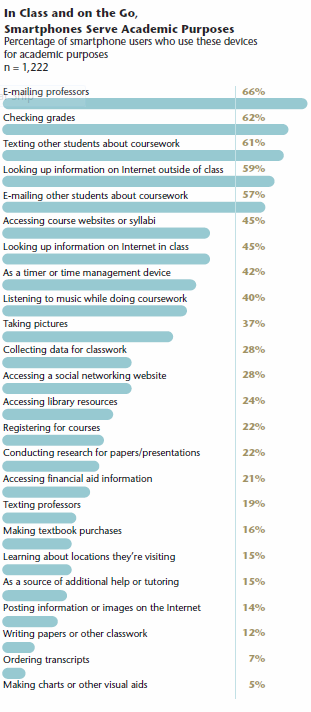

The ECAR National Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2011 reported, "More than one in three students (37 percent) have used an iPhone or another smartphone in one or more courses or academic activities in the past year. Forty-five percent of smartphone users have used these devices to look up information on the Internet in class."8 This study included 3,000 college students from 1,179 colleges and universities. The accompanying chart from the same report shows smartphone users using their devices for a variety of academic purposes.

© 2011 EDUCAUSE. CC by-nc-nd

Is device ownership growing?

Data show smartphone ownership in the general public is increasing. For example, the Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project reports that "Nearly half of American adults are smartphone owners."9 The Pew data show adult ownership of cellphones at 87 percent, with 46 percent of all adults owning smartphones. Additionally, the report shows an increase in smartphone ownership across the demographics of gender, age, race, income level, education, and locality (urban, suburban, or rural) when compared to Pew's 2011 report. Data in this report show that in 2012 20 percent of cell owners now describe their phone as an Android device, 19 percent as an iPhone, and 6 percent as a BlackBerry (and noted that BlackBerry percent of ownership is decreasing). From the same report:

"Nearly every major demographic group — men and women, younger and middle-aged adults, urban and rural residents, the wealthy and the less well-off — experienced a notable uptick in smartphone penetration over the last year, and overall adoption levels are at 60 percent or more within several cohorts, such as college graduates, 18–35 year olds, and those with an annual household income of $75,000 or more."

Methodology

A web-based survey was fielded to all NPS resident and distance-learning graduate students during the 2010 summer quarter and to all USNA undergraduate students in the 2011 spring semester. The target population for the NPS survey was all 2,601 resident and distance-learning graduate students enrolled in a degree program in the summer of 2010. The target population for the USNA survey was all 4,484 USNA undergraduate students enrolled at the time of the survey in 2011.

Instrument Description

The survey instrument was designed to obtain student feedback about their mobile device usage and their interest in using such devices for mobile learning. The final instrument consisted of 38 questions divided into the following four main sections:

- Current Device Ownership. Questions in this section asked students about the devices they currently own, including smartphones, PDAs (a category that was defined to include tablet-style computers), mp3 players, and e-book readers. If a student answered yes to owning any category of device, they were asked follow-on questions about the specific device or devices owned.

- Device Connectivity. Questions in this section asked students whether they paid for commercial wireless ("Wi-Fi") capability for their device or devices and, if so, the type of data plan used. These questions were intended to gain insight into whether students would be limited by data plan constraints and/or incur additional costs to access educational materials on their mobile devices

- Device Usage. Questions in this section asked students for examples of how they were using their mobile devices and, in some cases, for the students to identify how often they use certain functions on their devices. These questions allowed the survey to identify applications or software tools students are most comfortable using.

- Future Interest. Questions in this section asked students to identify educational tools and handheld devices they would be interested in having access to or purchasing. This section thus differed from the rest of the survey, which mainly focused on what students currently have and use, with questions about what they would like to have. The point of this section was to gain some insight into potential future trends in mobile learning.

Instrument Design and Pretesting

Following standard survey design principles,10 the questions and instrument were crafted in consultation with CED3. Upon completion of the initial design, the instrument underwent extensive pre-testing, again using standard methods.11 Beginning with expert review by CED3, the survey was tested via three stages of cognitive interviewing designed to: (1) ensure consistent respondent comprehension of the questions, (2) the proper flow of the survey instrument, and (3) overall survey design, including the correct skip logic coding and proper software operation. Pre-testing was conducted on representative members of the NPS student body, including foreign military officers for whom English was not their first language. Survey pre-testing culminated in a mock fielding of the survey at NPS to ensure all aspects of the survey, from respondent e-mail notification through data collection and downloading, were fully operational. During the mock fielding it was determined that respondents took about 10 minutes on average to complete the survey. A copy of the final survey instrument (NPS variant) is available at http://faculty.nps.edu/rdfricke/frickerpa.htm.

Fielding Procedures

The surveys were conducted entirely electronically, and they were fielded to the two student bodies via commercial software packages. For both, the fielding period was approximately a two-week period. Following good survey practice, potential respondents were first sent a pre-notification e-mail announcement. This was followed the next day by a second e-mail that invited the respondents to take the survey and included a URL link to the web survey. Non-respondents were then contacted up to three more times, roughly every two to three days, requesting that they take the survey. The notification and non-response e-mails were appropriately managed to ensure that, once students took the survey, they were removed from the non-respondent e-mail listing.

Response Rates

The USNA survey achieved a response rate of 24.8 percent (1,114 out of 4,484 students). The NPS survey achieved a total response rate of 71.2 percent (1,851 out of 2,601 students). The resident students' response rate was 72.5 percent (1,328 out of 1,831 students) while the distance-learning students' was 67.9 percent (523 out of 770 students).

Results

In this section we review and compare responses of both survey groups. Survey responses rarely showed significant differences among class years (in the case of USNA respondents) or between resident or nonresident status (in the case of NPS respondents); therefore, we report aggregate results across these categories. Most differences between USNA and NPS students were statistically significant (using Pearson's chi-squared contingency table test, with continuity correction where appropriate); all tests were performed at the .05 significance level.

Smartphones

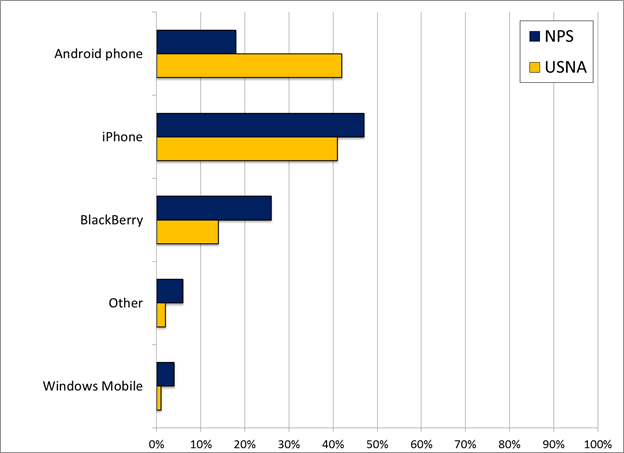

A majority of respondents (63 percent at USNA and 58 percent at NPS) owned smartphones; a substantial majority of these had unlimited data plans for these phones (87 percent at USNA and 83 percent at NPS). For those who indicated smartphone ownership, figure 1 shows type of smartphone owned. (Throughout, as applicable, table percentages do not necessarily add up to 100 due to rounding.) Nearly half of smartphone owners in both populations owned iPhones. USNA respondents owned more Androids and fewer BlackBerrys than their NPS counterparts; this may be due to the fact that BlackBerry devices are sometimes issued to active-duty officers, who comprise the majority of the NPS resident student population.

Figure 1. Of those who indicated owning a smartphone, "Which type of smartphone do you own?"

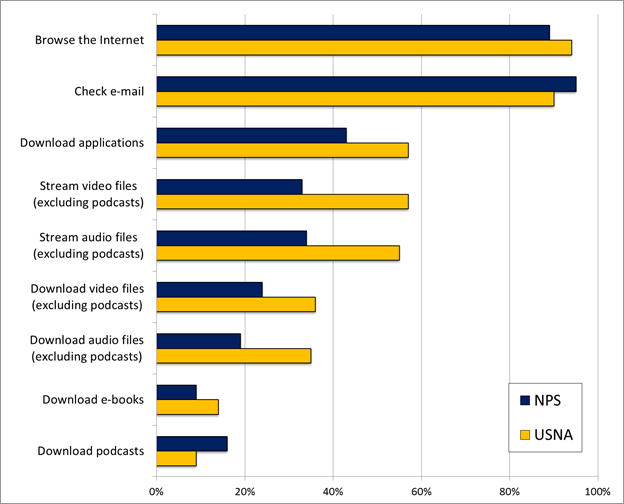

The dominant smartphone activities for both populations, aside from conventional phone conversation, were browsing the Internet and checking e-mail. Figure 2 shows the percentages of smartphone users who engaged in various activities at least weekly. USNA users engaged in most of the listed activities more frequently than NPS users.

Figure 2. Percentages of smartphone users who engaged in these activities at least weekly.

Of course, these activities may be driven as much by what's currently available as what students would like to do. For example, one respondent said, "I have used several learning applications for foreign languages on iPhone applications. The great thing about that is that you can have a chance to learn a new thing whenever it is not convenient for you to do anything in circumstances like when you wait in line get on a bus etc."

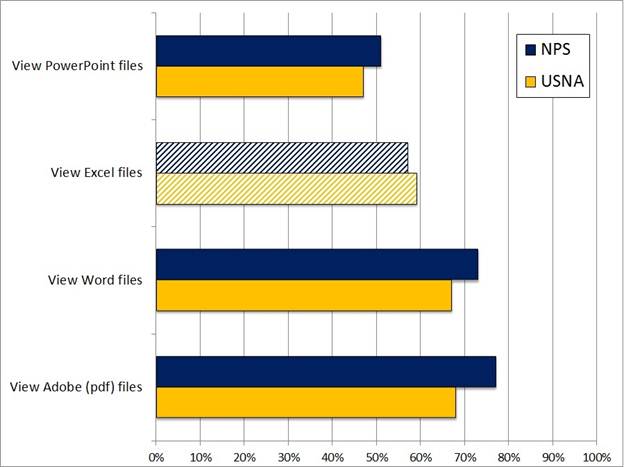

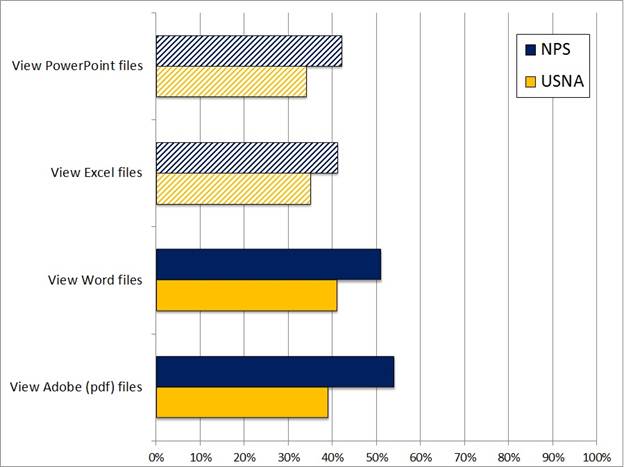

Figure 3 shows that about half to three-fourths of students used their smartphones to view files in Adobe, Word, Excel, or PowerPoint format; NPS students used smartphones for this purpose slightly more than USNA students. In the figure cross-hatching indicates the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 3. "Do you do the following using your smartphone?" Cross-hatching indicates differences are not statistically significant.

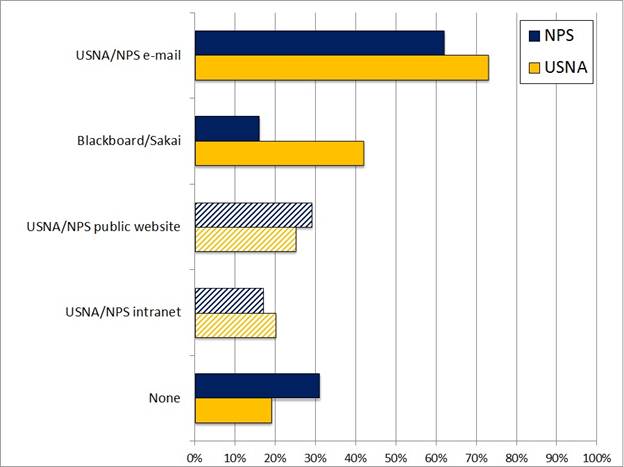

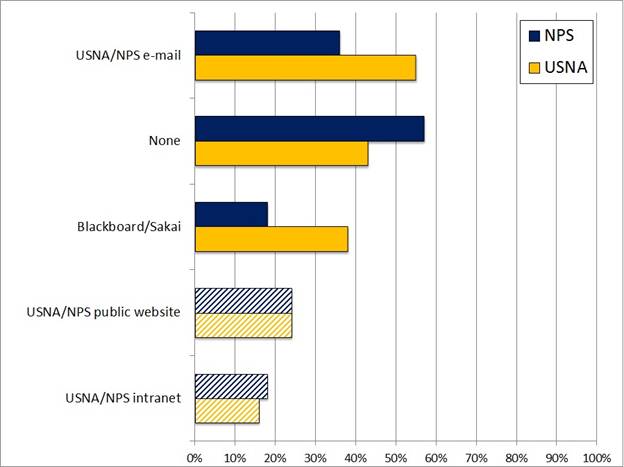

Figure 4 suggests that the primary "educational use" of smartphones consisted of accessing school e-mail accounts: nearly three-fourths of USNA students and nearly two-thirds of NPS students used their phones for this purpose. Less than one-third of students used their phones for any other particular educational use. Cross-hatching indicates differences are not statistically significant.

Figure 4. "Do you use your smartphone to access the following USNA/NPS educational tools?"

Tablet PCs and PDAs

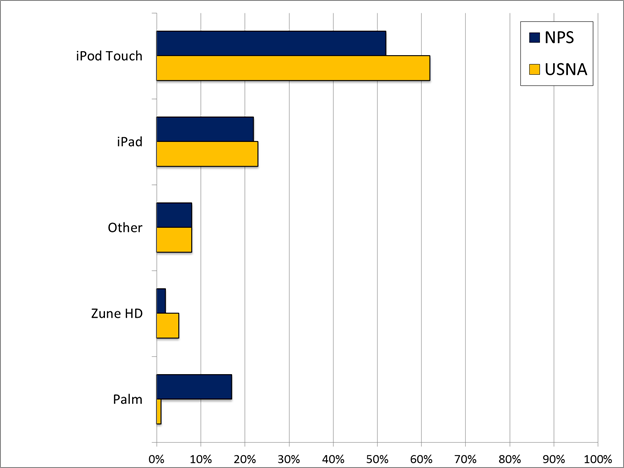

Less than a fourth of respondents (20 percent at USNA and 22 percent at NPS; difference not statistically significant) owned tablet PCs or PDAs. Figure 5 shows the most-used tablet PC or PDA by type. Most of those who owned a tablet PC or PDA primarily used the iPod Touch, and a strong majority primarily used either the iPod Touch or iPad. While less than one-fourth of respondents at both institutions reported primarily using iPads, we suspect that iPad ownership and usage percentages among the USNA and NPS demographics have grown since the time of this survey (since the iPad only arrived on the market in the spring of 2010). Similar to the case of smartphones, USNA respondents owned far fewer Palms than their NPS counterparts; this may be due to the fact that in some cases Palm devices are issued to active-duty officers in the line of their duties. The distribution of NPS students across all the categories was statistically different from that of USNA students.

Figure 5. Of those who indicated owning a PDA, "Which type of PDA do you own?"

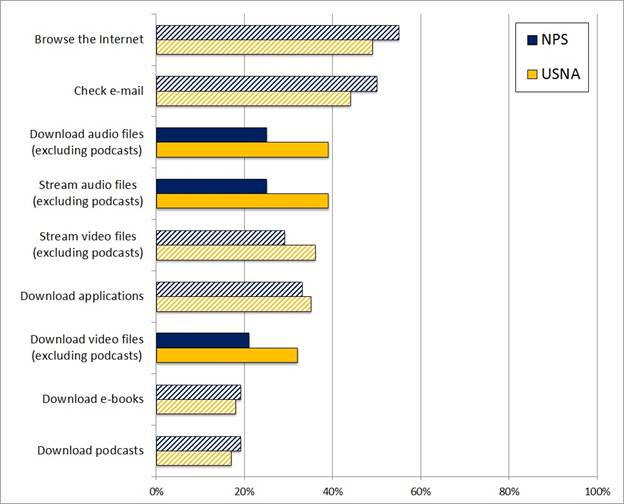

As with smartphones, browsing the Internet and checking e-mail were the dominant tablet PC or PDA activities for both populations. Figure 6 shows percentages of smartphone users who engaged in various activities at least weekly. Usages were comparable between the two groups, although USNA users engaged in audio and video file activities more frequently than NPS users. Cross-hatching indicates the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 6. Percentages of PDA users who engaged in these activities at least weekly.

Approximately half or fewer of the students used their tablet PCs or PDAs to view files in Adobe, Word, Excel, or PowerPoint format. Figure 7 shows that, as in the case of smartphones, NPS students used tablet PCs or PDAs for this purpose slightly more than USNA students. Cross-hatching indicates the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 7. "Do you do the following using your PDA?"

Interestingly, more than half of NPS students (57 percent) and nearly half of USNA students (43 percent) reported no tablet PC or PDA use for the educational options listed. Figure 8 shows that, as with smartphones, accessing school e-mail accounts was the primary "educational use" of tablet PCs or PDAs among respondents at both schools. Cross-hatching indicates differences are not statistically significant.

Figure 8. "Do you use your PDA to access the following USNA/NPS educational tools?"

mp3 Players

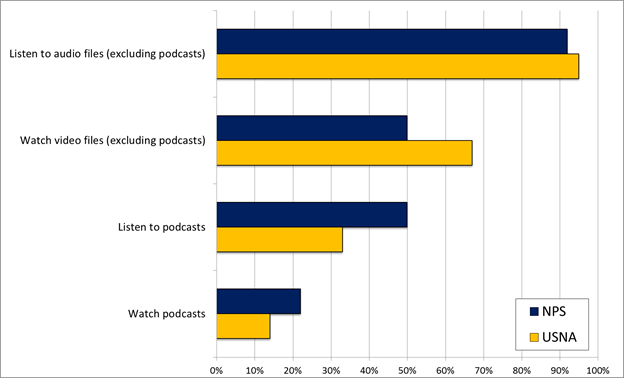

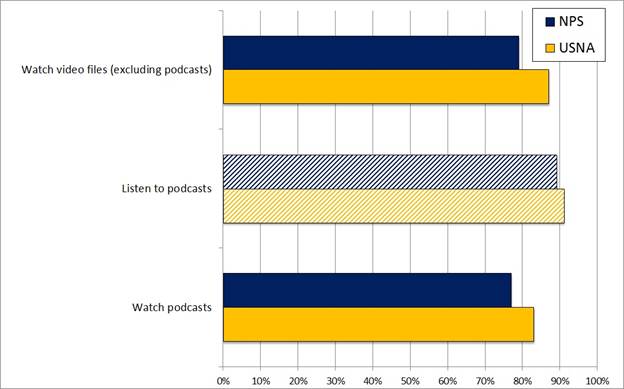

Approximately three fourths of respondents (77 percent at USNA and 72 percent at NPS) owned mp3 players, mostly iPods (91 percent at USNA and 81 percent at NPS). Figure 9 shows that nearly all respondents used their players for listening activities; a majority of USNA students used their mp3 players for viewing activities as well. Fewer NPS students used their players for viewing. Figure 10 shows that, by a small margin, USNA students had more capable mp3 players than NPS students. Cross-hatching indicates the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 9. Percentages of mp3 users who engaged in these activities.

Figure 10. Percentages of mp3 users capable of performing the listed activities.

E-book Readers

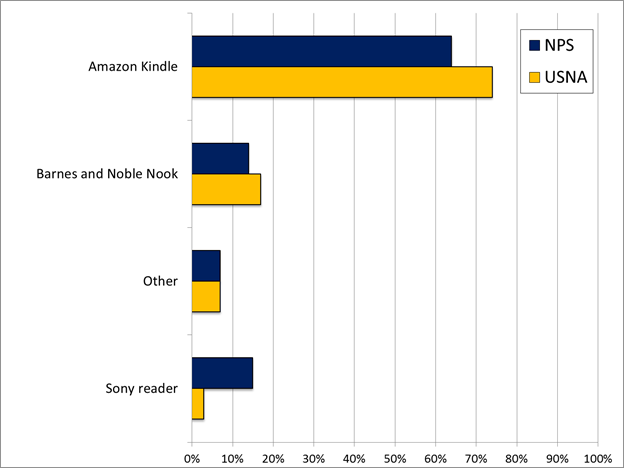

Among the device types involved in this survey, e-book readers were owned least (18 percent ownership at USNA and 9 percent at NPS). Among those who owned e-books, the majority owned Amazon Kindles (74 percent at USNA and 64 percent at NPS). In figure 11 the distribution of NPS students across all the categories was statistically different from that of USNA students.

Figure 11. Of those who indicated owning an e-book reader, "Which type of e-book reader do you own?"

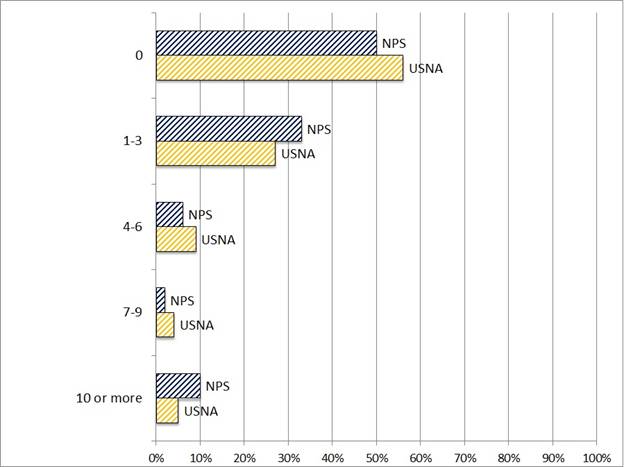

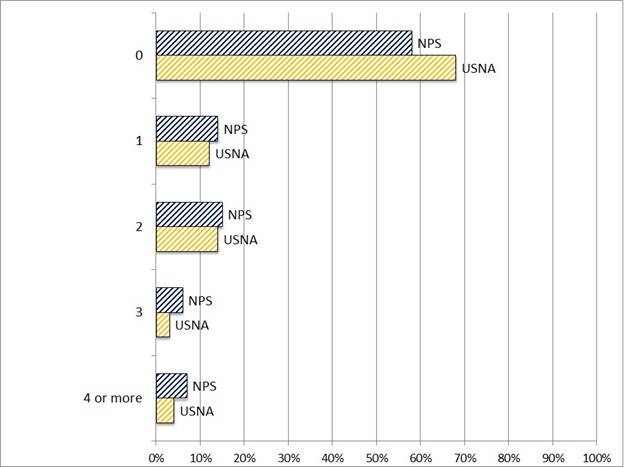

Figures 12–14 suggest that respondents at both schools tended to employ their e-book readers for personal use much more than for use in support of their school curriculum. Indeed, most respondents did not use their e-book readers for any curriculum-related readings. About one-half read at least one curriculum-related newspaper or magazine. Meanwhile, over 90 percent in each group read a least one personal book per semester on their e-book reader. Furthermore, USNA students tended to download more books for personal use than their NPS counterparts. Cross-hatching in these figures indicates the distribution NPS of students across categories was not different with statistical significance from that of USNA students.

Figure 12. "On average, how many newspapers and magazines related to your curriculum do you download using your e-book reader per semester?"

Figure 13. "On average, how many textbooks or other books required for classes do you download using your e-book reader per semester?"

Figure 14. "On average, how many books for your personal use do you download using your e-book reader per semester?"

General Interest

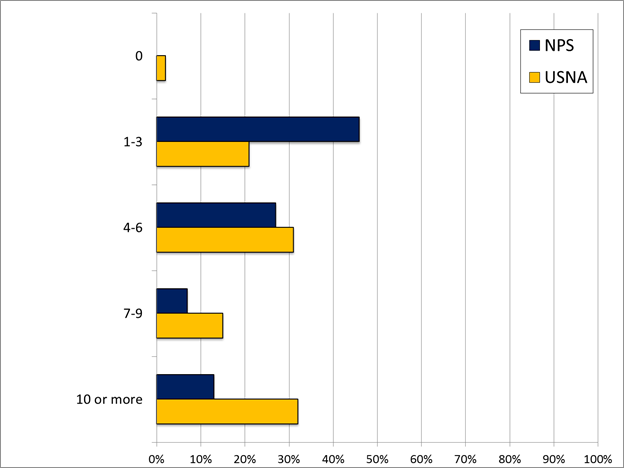

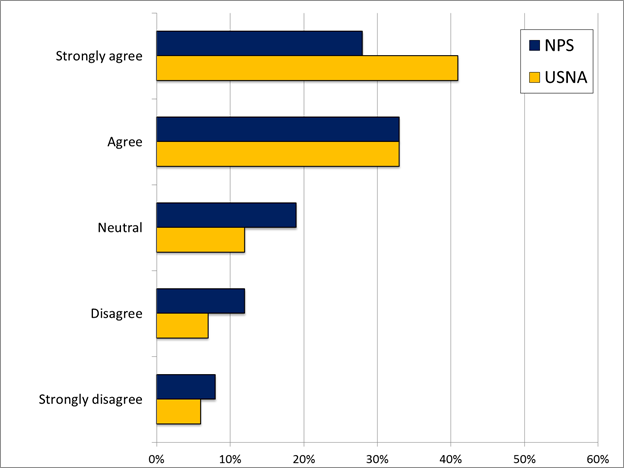

The previous results of this section suggest that, in general, respondents to this survey tended to use their mobile devices more for personal use than for formal educational use. In fact, an overwhelming majority of respondents stated that they had not used mobile learning on their handheld mobile device in the past (92 percent of USNA undergraduates and 87 percent of NPS graduate students). At the same time, solid majorities in both populations (74 percent at USNA and 61 percent at NPS) "agree" or "strongly agree" that they would use mobile learning on their hand-held devices if it were available in their curriculum (see figure 15). The distribution NPS of students across all the categories was statistically different from that of USNA students.

Figure 15. Response to, "I would use mobile learning on my handheld device if it were available in my curriculum."

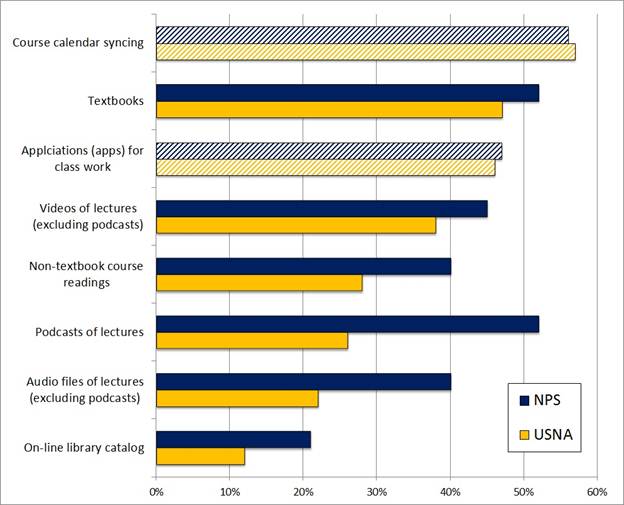

Figure 16 shows student interest in various types of educational materials that might be accessed via mobile devices. About half of respondents at both schools indicated interest in accessing course calendar syncing, textbooks, and applications (apps) in support of class work. At NPS, about half of respondents also expressed interest in mobile access to videos or podcasts of class lectures. USNA students seemed less interested in accessing lecture material (in any format) than their NPS counterparts. Cross-hatching indicates the difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 16. Response to "Which educational material(s) would you like to access on your hand-held mobile device?"

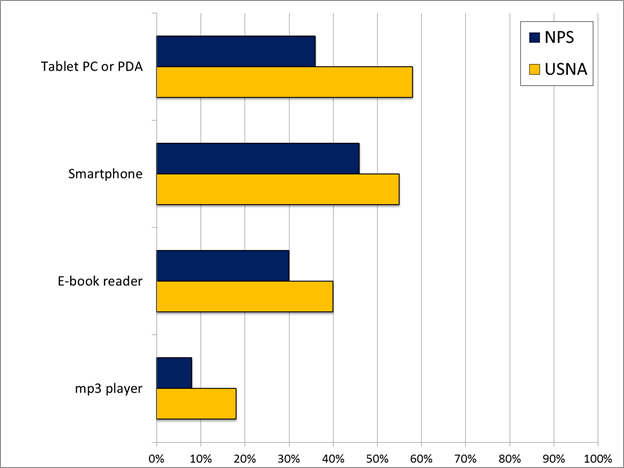

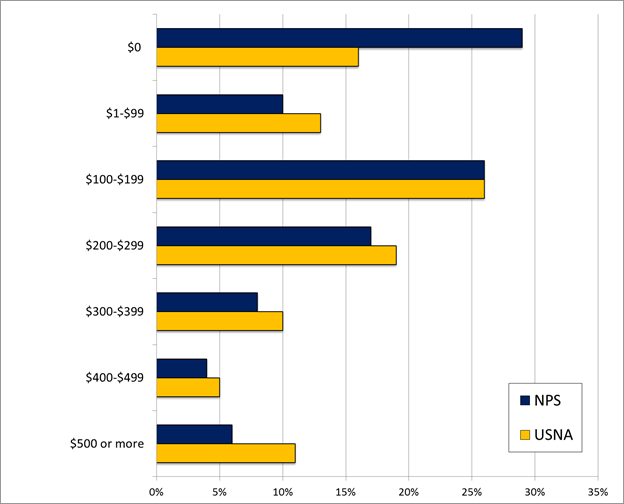

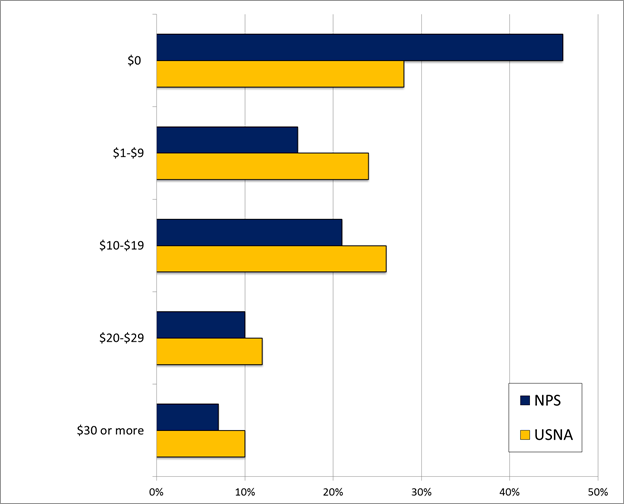

Figure 17 shows that most USNA respondents would be interested in purchasing or upgrading to a smartphone or tablet PC or PDA for accessing educational tools, and nearly half would purchase or upgrade to an e-book reader. Fewer NPS students expressed interest in purchasing or upgrading, but many of those who said they would not spend any money already owned one or more mobile devices with an unlimited data plan. Figures 18 and 19 indicate how much money students would be willing to spend on devices or upgrades. USNA students, the younger of the two groups, indicated a greater inclination toward such spending.

Figure 17. Response to "If USNA/NPS educational tools were available for mobile learning, which handheld device(s) would you be interested in purchasing or upgrading to?"

Figure 18. Response to "How much are you willing to spend on handheld mobile devices to access USNA/NPS educational materials?"

Figure 19. Response to "How much are you willing to spend on adding/upgrading your data package to access USNA/NPS educational tools per month?"

Discussion and Conclusions

This research assessed mobile learning trends via a survey of undergraduate and graduate students at the U.S. Naval Academy and the Naval Postgraduate School. Comparing our results to the results of the Pew "College Students and Technology" report, the rates of cell phone, laptop, mp3, and e-book reader penetration are very close.12 Similarly, while we did not ask students about smartphone use to the level of detail of the ECAR National Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2011,13 our results are consistent. This leads us to believe that our student populations, while in specialized curricula, are reasonably representative of the larger U.S. undergraduate and graduate student populations.

Research Questions Redux

We thus return to the three research questions with some assurance that our results are generalizable to other U.S. universities.

Question 1: What are the trends in mobile device usage by today's students?

In a single word, increasing. Our surveys show that a majority of our student populations say they would use mobile learning if it were available: 55 percent of NPS distance learning graduate students, 60 percent of NPS resident graduate students, and more than 70 percent of USNA undergraduate students. In terms of trends, note the inverse relationship to median age, where the younger the student body, the higher the fraction of students interested in mobile learning. This suggests that the interest in, and demand for, mobile learning will only continue to grow.

To those of us in the classroom, the trend is visibly apparent. Five years ago not all students had laptops; now virtually all of them do. Within the past five years it has become routine to see students using their laptops in class. Smartphones in the classroom are now at about the point laptops were five years ago, where even just a year or two ago it was a novelty for a student to use his or her smartphone to look up something and contribute it to the classroom discussion. Today that is becoming normal.

Question 2: Which types of course content do current students prefer for their mobile devices and in what format?

Almost all students use their smartphones for e-mail and web browsing, and approximately half of students also use their smartphone for streaming or downloading audio and video files. However, only about one in 10 students use their smartphone for e-books and podcasts. This trend roughly holds for PDA usage, though usage is lower in all categories except for e-books and podcasts. And, while virtually all mp3 owners use them for listening to audio files, almost half of them also use them to watch video files. In general, undergraduates do more things on more devices than do graduate students, which also supports the conclusion that the demand for mobile learning is likely to increase.

About the only set of questions in which the NPS graduate students consistently showed higher percentages than the USNA undergraduates was in their desire to use smartphones and PDAs to view PDF, Word, Excel, and PowerPoint files. However, because type of student (undergraduate/graduate) is confounded with institution (USNA/NPS) in our surveys, these results may be due to differing pedagogy, institutional infrastructure, and policies and not to age.

Comparing between the undergraduate and graduate students in our surveys, we can clearly see a shift from the dominance of the iPhone a few years ago to near parity between Android-based phones and the iPhone. That hardware-specific difference between the two populations aside (which is likely driven more by the marketplace than by relevant student differences), these results show that in general the undergraduate students use their smartphones and most other mobile devices to do more things with higher frequency. The USNA undergraduates also indicated interest in purchasing handheld devices for mobile learning in greater numbers. This again suggests a trend toward increasing demand for mobile learning.

Question 3: What will future university students expect schools to provide on their mobile electronic devices?

Focusing on the USNA undergraduate population, there is strong interest in a variety of educational tools. In addition to e-mail and web browsing, students want to be able to access course management systems like Sakai and Blackboard, and they want to be able to sync course calendars across their devices, mobile and otherwise. Students also want electronic access to course textbooks and other course reading materials. Furthermore, they want mobile applications that support class work, and they want audio, video, and podcasts of class lectures.

That said, universities need to ensure that mobile device access is seamlessly integrated with other IT services. As one respondent said,

"Non-integrated web-based solutions are frustrating at times. Multiple log-ins, separation of needed information, etc. make it very time consuming to do things from a mobile device. These types of applications work OK from a computer, but are not simple enough from a mobile device to want to use."

In addition, further research is required to better understand how each device is best used for learning. For example, a common refrain from survey respondents is that smartphone screens are too small:

"The issue with accessing information via mobile devices is the size of the screen. You can't read entire articles or view lectures comfortably on a 2 in by 3 in screen. You would also miss out on the interactive learning process."

Similarly,

"Audio lectures covering history and such are good for mobile devices, but my distance course deals with an enormous amount of math. As it is, I prefer to watch lectures on a large laptop rather than on my netbook so I can clearly see the problems worked out by the instructor."

What Does All of This Mean?

So, what does all of this mean for university-level IT infrastructure? Our survey results, and those of others, suggest that investing resources in developing mobile learning tools is worthwhile, at least from the point of view of what students desire. For one thing, handheld device use is ubiquitous among students, and although most of this use is personal, a significant majority of students express an interest in using mobile learning on their handheld devices. Furthermore, most students said they are willing to spend money to upgrade their mobile devices to access educational materials, and, of those not interested in purchasing or upgrading, over half already own a smartphone. So, students are interested in mobile learning to the extent that they will invest their own money to take advantage of the technology.

From a media development point of view, our results seem to indicate that developers ought to be producing mobile materials that run on both Android and Apple devices. Such efforts for BlackBerry devices perhaps need not be a priority. (As one respondent said, "I don't like my Blackberry because it has limited functionality for applications. I plan to upgrade to a Droid or iPhone this year.") It also appears that, for now, it is not necessary to develop materials specifically for e-book readers. However, trends regarding e-book reader usage should be watched, as it is unclear whether tablet PCs or PDAs, e-book readers, or other devices will emerge as the preferred tool for electronic reading.

What does this mean for the future of teaching and pedagogy? The surveys did not speak directly to this question, but combining what we've learned from them and from our experiences in the classroom, we have some thoughts:

- First, it's pretty clear that the days where the only mode of learning is students sitting together in a classroom taking notes on paper while the professor writes on a blackboard are waning. Today the classroom is becoming more and more electronic, with students taking notes on tablet and laptop computers while they look things up on their smartphones. Instruction is going electronic as well, where these days one of us teaches almost entirely by writing on a tablet computer that is projected to students, some who are sitting in the physical classroom and others who are participating from afar in a virtual classroom.

- Second, as students continue to expand their use of electronic, Internet-enabled devices, teaching will need to adapt. Some of this adaptation will involve figuring out how to incorporate these devices into the standard classroom-based teaching paradigm so they enhance learning. It will also involve figuring out how to most effectively conduct distance and distributed learning, a rapidly expanding teaching mode that depends heavily on various types of technology, most of which is Internet-enabled. And, it will also involve ensuring existing residence and distributed-learning infrastructure works with and on students' preferred devices, including adapting and porting infrastructure to the hardware technology (such as mobile devices) and software tools (such as social networking media) that students prefer.

This last point is nicely illustrated by a recent survey of NPS students about their library. While never explicitly asked in the survey, one of the more common refrains in the students' open-ended comments was a request that the library implement a Google-like search capability on the library webpage. At issue was that the library website was designed around a set of legacy and proprietary search engines, each focused on some part of the library's collection, and each requiring some fairly specialized search query knowledge and syntax. But in the age of Google, students now expect to be able to type freeform text in a single search box to search the library's entire collection. They certainly don't understand the need to learn or use complicated search query syntax, and they want ease of access from their smartphones and other mobile electronic devices. To its credit, the NPS library heard this feedback and has recently implemented exactly this type of Google-like search capability to great acclaim — a perfect example of adapting the existing infrastructure to changing student expectations and needs.

How can we best use mobile devices in the classroom to enhance learning? That's less clear to us, though obviously it will depend on the specific details of the subject being taught. We expect that courses requiring a more interactive or discussion-style of teaching, and particularly those that require the use or synthesis of many disparate information sources, are likely to benefit from the use of mobile learning devices. Similarly, classes based on significant student-to-student interaction, either inside or outside of the classroom, will likely benefit from mobile learning devices. However, mobile devices may have less of a role in curricula that require more lecture-style courses, though even in these environments we have seen mobile devices used productively (e.g., to solicit real-time student feedback during the lecture). That said, as we consider the place of mobile learning devices, it is important to keep in mind that some students still prefer to use traditional methods and modes. For example, one survey respondent said, "[The] iPod is nice to listen [to], or watch lectures or textbooks. However, I still prefer to read and mark-up textbooks or handouts because of my need to easily reference the material later."

Mobile devices also constitute a double-edged sword, where anyone who has taught in a classroom with students who have laptops or smartphones has observed how some students are clearly distracted because they are busy browsing the web, sending e-mail, or texting rather than paying attention in class. Some of our colleagues have addressed this problem by banning electronic devices in their classrooms, but that also excludes the benefits these devices can bring, and such an approach only works in resident classes when all the students are physically located in the same space. One solution is to transition from a process-based learning approach, where every student is expected to go through the same pedagogical process, to an outcome-based approach, where the each student's path may be different or customized (and at a minimum is not dictated to be exactly the same) and where successful completion is judged according to one or more outcome-based measures (tests, papers, etc.). However, whether this or some other approach is best is an open pedagogical issue, and best practices for effectively integrating mobile and other electronic devices into the classroom have yet to be determined.

Thus, to us, the big question is not whether to transition to mobile technology, but how. Clearly the mobile learning technology is in place, the demand is there and growing, and neither is going away in the foreseeable future. As Eleanor Roosevelt said, "The future is literally in our hands to mold as we like. But we cannot wait until tomorrow. Tomorrow is now."14

Take Our Survey

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our thanks to Ms. Lou Cox and the USNA Institutional Research Department for fielding the USNA portion of this survey. And we would be remiss if we did not acknowledge all the students in Professor Fricker's 2010 Survey Research Methods class, led by Tino de la Cruz, who conducted the initial survey design and collected the NPS data. They are Alice Adams, April Bakken, Will Corley, Jason Dao, Edwaun Durkins, Chris Ewing, Charles Farlow, David Hooper, Ken Jackson, Brendon Key, Randi Korman, Jason Lin, Kevin Moeller, Christina Schmunk, Sam Shearer, and James Walliser.

- Larry Johnson, Rachel Smith, H. Willis, Alan Levine, and Keene Haywood, The 2011 Horizon Report (Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium, 2011).

- ITU, "The World in 2011: ICT World Facts and Figures," mobiThinking (2011).

- Johnson et al., 2011 Horizon Report.

- Ibid.

- Lee Rainie, "Tablet and E-book Reader Ownership Nearly Double Over the Holiday Gift-Giving Period," [http://cms.pewresearch.org/pewinternet/files/2012/03/Pew_Tablets-and-e-readers-double-1.23.2012.pdf] Pew Internet & American Life Project, January 23, 2012.

- Sian Lindsay, Ajmal Sultany, and Kate Reader, "An Investigation into Student Mobile Devices, at City University, London," City University London, Learning Development Centre and the Schools of Arts and Social Sciences, April 16, 2010.

- Julie Lynn Mueller, Eileen Wood, Domenica De Pasqual, and Ruth Cruikshank, "Examining Mobile Technology in Higher Education: Handheld Devices In and Out of the Classroom," International Journal of Higher Education, 1 (2) (2012): 43–54.

- Eden Dahlstrom, Tom de Boor, Peter Grunwald, and Martha Vockley, The ECAR National Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2011 (Research Report) (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2011).

- Aaron Smith, "Nearly half of American adults are smartphone owners," Pew Internet & American Life Project, March 1, 2012.

- Don A. Dillman, Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method — 2007 Update with New Internet, Visual, and Mixed-Mode Guide, 2nd edition (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2006); and Robert M. Groves, Floyd J. Fowler, Jr., Mick P. Couper, James M. Lepkowski, Eleanor Singer, and Roger Tourangeau, Survey Methodology (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2004).

- Floyd J. Fowler, Jr., Improving Survey Questions: Design and Evaluation (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995).

- Aaron Smith, Lee Rainie, and Kathryn Zickuhr, "College Students and Technology," Pew Internet & American Life Project, July 19, 2011.

- Dahlstrom et al., ECAR National Study.

- Paul F. Boller, Presidential Wives: An Anecdotal History (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999).

The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.