Key Takeaways

- Technology can help fight cheating that is itself based on technology, especially with tweaking of assignments and assessments in a way that makes it difficult to cheat.

- Students should be made aware of resources such as university writing centers and tools such as Endnote.

- Training about copyright, plagiarism, and time management can help students succeed without feeling that they have to cut corners.

- Relevant codes and policies should be clearly stated in communications such as orientation materials, student handbooks, and course syllabi to establish expectations and reduce confrontations between instructors and students.

Academic integrity can seem like a nebulous concept, though it is probably better understood through its opposite, academic dishonesty: that is, "…anything that gives a student an unearned advantage over another."1 It involves our understanding of ethics, culture, pedagogy, and even technology. Ethical lapses during one's education may carry over into a person's career and personal life. With the growing number of corporate scandals, educational institutions could increasingly be held accountable for providing training in ethical behavior. Improving academic integrity not only preserves the integrity of an assessment, a class, or an academic program but also serves as part of an ongoing education that enables a person to grow as a learner, an employee, and a public citizen.

William Astore, a professor of history at Pennsylvania College of Technology, dismisses the division between an "academic world" and a "real world." Professor Astore argues that "education is indeed a real world, every bit as vital and true as the world of work." I have worked both in the corporate and academic settings myself. While working for universities, I found them to be places where people work, learn, relate, and grow as much as (and often to a greater extent) they do in other work settings. Insisting on academic honesty helps students learn to take greater responsibility for their learning and personal conduct, which is "real world" in every sense of the phrase.

Confronting academic cheating can ultimately help students grow. Initially they may be less concerned about academic ethics than about peer, parental, and financial pressure to succeed, and although the nature of these pressures may vary from culture to culture, they are to some extent present everywhere. Higher education institutions must help students understand that embracing academic integrity is a necessary part of achieving success.

Is Technology the Culprit?

Technology is sometimes blamed for "causing" academic dishonesty at the present time. Students can easily use computers to plagiarize from Wikipedia or copy and paste from Google with just a few clicks. Online classes in particular lend themselves to this type of cheating.

Web-based resources have enabled students to change how they consume knowledge. Comments A. Nicole Pfannenstiel of Arizona State University:

In the age of blogs, mashups, smashups and Wikipedia, traditional notions about academic and educational integrity and appropriate acknowledgment of sources seem altogether out of synch with everyday, creative or artistic research and writing practices.

At Oklahoma Christian University (OC), we provide every student with an Apple laptop and another electronic device such as an iPhone, iPod, or iPad. The entire campus is covered by a wireless network. With our infrastructure, technology use is increasing, yet cases of reported plagiarism are decreasing. So ubiquitous technology appears not to be the controlling factor.

Because I work with educational technology, I often get involved in cases concerning academic integrity. In fall 2009, OC had 49 reported cases of academic dishonesty. In 2011, the total dropped to 19. In fall 2011, there were 14 reported cases. Our experience offers some thought-provoking ideas about the socio-technological aspects of academic honesty.

Strategies to Fight Dishonesty

By working with professors and investigating the relationship between technology and academic integrity, I have discovered several strategies for addressing the issue, which I will discuss individually. They involve:

- Preventive technology

- Design of assignments

- Alternative resources

- Training

- Honor codes

- University culture

Although various techniques can serve to detect or minimize cheating, universities have a greater responsibility to teach students about the ethical implications of academic cheating.

Use Prevention Technology

Yes, technology can be used to help fight cheating based on technology. While some professors and administrators complain about technology-related cheating, others have used technology to make cheating easier to detect and minimize. Students are increasingly aware that they leave digital footprints in their work. For instance, faculty can generate attempt statistics for tests that show when a test was started and ended, thereby invalidating excuses about not being able to log in to tests. As a last resort, screenshots of the relevant online activity can be provided to students to make them aware that excuses cannot be supported by the evidence. The more instructors use tools such as learning management systems, the easier it becomes to find out whether Blackboard truly ate someone's homework.

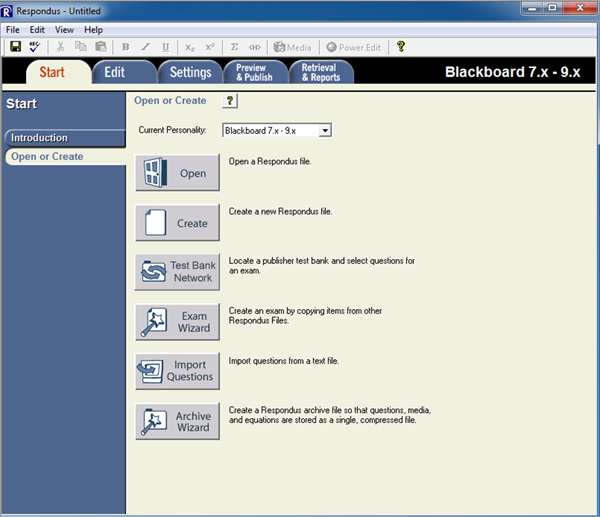

At OC we use the Respondus Lockdown Browser (which locks down the testing environment in Blackboard) to prevent students from searching for answers. Instructors can also generate random blocks of tests in Respondus (figure 1).

Figure 1. Generating random blocks of tests in Respondus

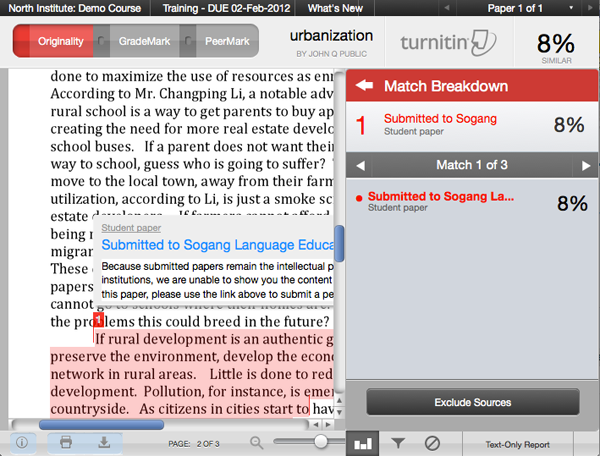

Programs such as Turnitin can help faculty check for originality and generate reports that show the sources of potentially plagiarized content, as well as the percentage of "matching" between a student's paper and an external source. The Turnitin screenshot in figure 2 shows one of my newspaper articles having an 8 percent matching rate with a paper from Sogang University. A student there quoted from my article and cited it properly. In this case, Turnitin shows matching that alerted me to possible plagiarism, although no plagiarism was involved.

Figure 2. Turnitin screen of content matching other publications

These initial warnings are very helpful to faculty, though. Moreover, the mere use of such programs has the effect of deterring student cheaters. As Phil Reagan, a professor in OC's Communications Department, told me:

"I use Turnitin as a plagiarism detection tool in all my classes where written papers will be submitted. At the beginning of each semester, I state both in my class syllabi, and in oral in-class instructions, the university's honesty policy, which states that plagiarism is not acceptable. I also explain that Turnitin will be used in class, and how Turnitin works to reveal plagiarism. Most students are familiar with the tool. Generally, I believe that Turnitin helps encourage honesty in student writing."

OC also has a Turnitin Building Block (which integrates with Blackboard) to collect student assignments. Faculty love such applications, though the tools require support and training. We should remember, however, that while technologies to detect plagiarism keep improving, students are also finding newer and better ways to cheat. An instructor might focus chiefly on acts of academic dishonesty on the computer only to find that small memory devices and cell phones are being used instead. For example, students can text their answers to peers. Relying solely on technological tools can be risky, hence the need to balance them with other strategies.

Design Alternative Assignments

Marilyn A. Dyrud of the Oregon Institute of Technology, writing in Business Communication Quarterly, thinks that prevention might be better than punishment and suggests using "creative methodology" for designing assignments. We at the North Institute sometimes also challenge faculty to consider that, if students working together raises concerns about cheating, proactively putting students to work in groups for group projects, collaborative wikis, class blogs, or discussions as alternative methods of assessments offers advantages as well. In addition, some assignments and assessments can be "tweaked" in a way that makes it especially difficult to cheat. For instance, instead of using the same exam repeatedly during different semesters, professors can develop a pool of questions and randomly draw a limited number of questions from the pool each semester, or even for each testing attempt. Such little tricks work well to fight cheating. Most learning management systems have functions that make such randomized tests very easy to design. Blackboard permits the building of random blocks for drawing questions from pools, and Respondus test-generating software (figure 1) lets test designers generate randomized question pools.

It is also a good idea to incorporate more Web 2.0 assignments such as blogging, social bookmarking, and podcasting in a course. Students become better motivated when contributing their original work, as their personal identity is involved. When their work is broadcast to their classmates and possibly to a wider world, they tend to be more cautious about using someone else's work.

There are also some philosophical considerations for designing alternative assignments. Academic cheating may result when students can consult unapproved sources. Virgil E. Varvel Jr. noted that in an online assessment students may bring "the entire Internet, along with friends or even paid helpers. All online assessments essentially become open book in nature." Although this sounds distressing for faculty looking to integrate technology into teaching, Varvel went on to say, "But life itself is open book."

Ken Parker, founder and CEO of NextThought, is trying to harness the power of the social network to aid the learning process. His company digitizes books and makes them socially interactive for all students. The implications for learning appear fascinating. He shared his thoughts with me by e-mail:

"Technology offers powerful new assessment techniques well beyond multiple choice tests. What if a student's entire digital history comprised their assessment rather than only a few high-stakes exams? One powerful example: tap into the online community's assessment of a student. A student's community interactions and contributions could be analyzed. How did the community feel about the quality of their questions (lame or great) or contributions (useless or helpful)? Not only would this type of assessment encourage greater engagement and helpful community behavior, it's harder to cheat the system (and the community)."

Parker's work raises a broader question: Should educators prepare students to be skilled closed-book test takers or should they prepare them to become lifelong learners skilled at using all the resources in their environment? Though traditional assessments are necessary to ensure that students internalize certain skills, knowledge, or attitudes, it is also essential for students to develop skills that enable them to learn in more informal settings where they are expected to consult colleagues, job aids, the Internet, and other performance support systems. An institution's academic program may be the only opportunity they have to learn those skills.

Offer Resources

Fighting academic dishonesty with nothing more than penalties can have negative side-effects, such as alienating students who can change and improve their behavior or offending students who do not cheat at all. Instead of viewing the entire student body as potential cheaters, institutions should create a supportive environment in which students can learn through positive reinforcements. Offering resources is one way to do that.

Many universities have rich resources that can help students succeed without their feeling that they have to cut corners. For instance, students can go to writing centers for help with their papers. I am often dismayed to find that many students do not know they can use Endnote, which our university provides to help them format their academic citations properly. There are occasions when the line between improper citation and academic cheating is blurry. Learning to use tools such as Endnote will better equip students to write papers meeting professors' standards. At OC I have been asked repeatedly to visit Professor Gail Nash's English classes to talk about the uses of Endnote. To her students, this is not just another technology orientation they can do without. She asks me to visit before students even start to formulate ideas for writing a research paper. As she explained:

"I want students to learn about EndNote as a research tool, not just a citation generator. Therefore, I try to expose them to EndNote early in their academic lives. … [E]ven if the students are already juniors or seniors I still want to introduce them to the role EndNote can play in gathering and organizing their research as well as the citation help."

Thus, using the technology is not an afterthought; it becomes part of the preparation for students when they do research. I also find that sometimes international students go online to search for articles to help with their writing, whereas they could go to the university library database to find more scholarly articles to help them develop better writing skills. To get students into the habit of using library databases, librarians of our university actually visit classes to show students how to use the library databases.

Provide Training

The Chronicle of Higher Education reported a study by the Council of Graduate Schools showing that "university administrators have struggled to improve training in research ethics as more and more cases of scholarly misconduct make headlines." The article found, for instance, that students depend heavily on advisors to understand what is ethical behavior in research. While advisors may play an essential role, I think universities should provide more deliberate, well-designed training on academic honesty.

Our university has developed an understanding that cultural expectations and academic differences confound issues about academic integrity. For example, the issue of intellectual property is not universally understood. Moreover, having to work in a language that is not one's own can be a substantial handicap. We track international students separately to better understand how culture and difficulties with English might affect academic integrity. To help students understand the proper boundaries, the university has made a conscientious effort to address plagiarism among international students, especially as their numbers grow. Providing language and writing resources has proved helpful. For example, L. J. Littlejohn, director of OC's Language & Culture Institute, described the following approach to training:

"Robin Hood is a story recognized by every student I have taught, regardless of where the student calls home. The character names may change, but the plot remains — an outlaw steals from the rich, only to give to the poor. Every student, without exception, has identified Robin Hood's guise as a savior to be wrong — he is a fraud. And fraud seems to resonate with students, both domestic and international, as wrong. Whether this 'wrong' is a moral, social, political, or character 'wrong' depends greatly on the lens the student wears to interpret the world — their culture. Academic integrity among international students demands the understanding of the host culture, and how its ethics and education are influenced by the culture. By providing international students not only with clear expectations of the necessity of academic honesty but also furnishing clearly stated rules of what academic honesty is, an institution can help the international student population understand the boundaries of what is and isn't plagiarism."

OC professors proactively address academic dishonesty. I have been asked several times to serve as an intermediary between professors and students. In a private faith-based institution, ethical behavior is critical to both the instructors and the administration. A special effort is under way to familiarize international students with the U.S. academic environment. At a symposium sponsored by the Language and Culture Institute and the North Institute for Teaching and Learning, we told students what is considered to be cheating in an American university, what the university would do to punish cheating, and what tools they could use to make proper citations. Perhaps as a result of these targeted efforts, the rate of cheating dropped faster for international students than for domestic students. In fall 2009, we had 18 reported cases of academic dishonesty among international students. In 2010, the total dropped to five, and it dropped to two in fall 2011.

The Rochester Institute of Technology uses a similar approach to help international students acclimate to the American academic environment, offering a copyright/plagiarism class during orientation. Programs like this should help minimize cheating.

Training should also be provided for other skills, such as time management. A student resorting to plagiarism to complete homework may have spent too much time on Facebook, for example. The issue might not be a social media issue but rather a problem of time and boundary management. Technology use and plagiarism can at times be correlational, but there is no causal relationship. According to a 2010 report, students who commit academic dishonesty tend to demonstrate behaviors of "poor time management, difficulty in acclimating to the college experience, or poor understanding of the proper use of intellectual property." Training in these areas would help.

Create Honor Codes and Policies

Perceptions of cheating vary. The insightful paper "Student Perspectives on Behaviors that Constitute Cheating" shows that there is substantial disagreement "not only between students and faculty, but also among students and among faculty." Lacking a common policy itemizing behaviors considered to be cheating, professors have great flexibility in deciding how to define it. This variance of understanding can lead to unpleasant confrontations between professors and students. It is therefore essential that universities develop and enforce explicit policies with regard to academic dishonesty, including in the use of technology. [See a related article about a student mistakenly accused of plagiarism because of a lapse in cyber security awareness. — Editor] Whether academic cheating is related to technology or not, universities should communicate the boundaries to students.

Marilyn A. Dyrud also suggests that honor codes and policies to make students aware of the ethical implications of academic cheating are helpful. I would recommend that relevant codes and policies be clearly stated in communications such as orientation materials, student handbooks, and course syllabi. When these policies are relegated to fine print, students tend to ignore them, often at their own cost. A more attention-grabbing communication method — including video clips — would help. Short, itemized statements about what individual professors perceive as cheating and what they and the university will do in reaction would also be helpful.

Grow a Culture of Integrity

We cannot teach behaviors of academic honesty if integrity is not part of the university's culture. If it is commonplace for faculty members to fabricate research data or plagiarize in their own papers, their behaviors will have a negative impact on their students.

Academic integrity is particularly important at OC, where the mission is to "transform lives for faith, scholarship, and service." The university mandates daily chapel attendance whereby students come together to hear talks about what it means to be a person of faith and integrity. Students participate in various outreach programs locally and internationally to promote their values. Faculty members are also evaluated by the service they provide to students, the university, and the local community. There is a strong culture of "service ministry" whereby staff, faculty, and students are expected to practice Christian discipleship. In such an environment, professors take student academic dishonesty very seriously, and offenses are strictly penalized. When students understand that faith and the behavior it entails are part of their OC experience, the university can better combat academic dishonesty.

Although habitual cheaters are not likely to prosper at OC, we realize that unfortunately there are still cases of academic dishonesty. Nevertheless, students find that improper behavior is incongruous with their general environment. When a culture of integrity grows, academic dishonesty drops, even when ubiquitous campus technology seems to make cheating easy.

Conclusion

I like William Astore's eloquent statement about academic integrity: "… [I]ntegrity gains intensity and shines forth like a beacon on a lighthouse, helping us all to avoid wrecking ourselves on the shoals of our own collective shallowness." On a campus where every corner is covered by Internet access and all students have sophisticated information technology devices, academic integrity may seem like just a technology-related problem. However, solutions ultimately lie in addressing deeper cultural issues as well.

- A. Mullens, "Cheating to win: Some administrators, faculty and students are taking steps to promote a culture of academic honesty," University Affairs, 41 (10), (2000): 22–28.

Berlin Fang is Associate Director of the North Institute for Teaching and Learning at Oklahoma Christian University.

© 2012 Berlin Fang. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article (September/October 2012) is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.