Key Takeaways

- What happens when an instructor implements social networking in undergraduate and graduate courses without crossing into the "friend" or "follower" zone?

- Problems engaging students through Facebook encouraged exploring the use of Twitter; the concept of "Twitical Thinking" resulted.

- Continuing efforts using social networks in university classrooms will inform future theories on their effective use and best practices.

Social networking has been increasingly advocated in educational settings; however, not all students are comfortable with this practice. Educators typically use social networks to disseminate information and remain in communication with students throughout a course. In this article, I describe the unsuccessful use of Facebook in one of my courses, and then compare this experience to "Twitical Thinking" as an effective approach to engaging students in class discussions.

Overview

As a former K–12 teacher and a current educator in higher education, I grappled with the idea of creating a Facebook account to communicate and become "friends" with my students. I was less concerned with using Twitter because of the difference between "following" and "friending." In my youth I was told by parents and teachers, "I'm not your friend." They said this to distinguish between the roles of friends and adults in the rearing of a child. An assumed level of respect was maintained between teacher-student and parent-teacher when such boundaries were made clear. Today's shift in learning environments to learner-centered classrooms thus raises these questions:

- Do educators now want to be friends with their students?

- Do students actually prefer not to be friends with their teachers?

Although some educators are reluctant to "friend" students, students exhibit a similar response to "friending" faculty.1 College students regularly posting to their Facebook pages might suggest that they would find it convenient to use the same social networks for communication in courses. A study examining faculty and student use of social networks found that 47 percent of undergraduates surveyed thought it was convenient to use Facebook in the classroom. Although 27 percent of everyone surveyed welcomed the opportunity to connect with faculty/students online, 22.5 percent considered Facebook personal, not for education, and 15 percent articulated apprehension about the potential violation of their privacy.2

Despite concerns about using Facebook in the classroom, I created a group for my students to join in one course and implemented the use of Twitter in another. Facebook use was optional; the use of Twitter was required.

More about the Students and Courses

I teach undergraduate and graduate students at a midsized private university in Southern California. The course that used Facebook, titled Educational Applications of Technology (EAT), is primarily taught online and is a requirement for special education teacher candidates, as well as single-subject and multiple subject credential candidates. Additionally, this course is a requirement for undergraduate students with a Bachelor of Arts minor in the Integrated Educational Studies (IES) program. The course that used Twitter is a requirement for the undergraduate IES students only.

Facebook and Friending

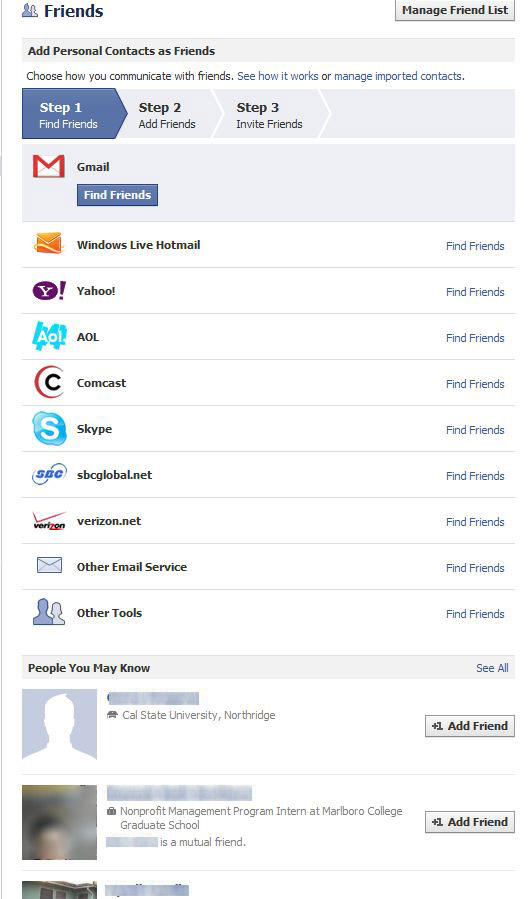

The term "friend" used to refer specifically to people you actually cared about or shared personal encounters with on a regular basis. You could probably drive to their house without a GPS and recite their phone number by memory. We used to befriend each other based on some form of connection through offline interactions. What does it mean to be a friend on Facebook?3 It can mean the same thing, or maybe you met someone once and then searched Facebook to find them again — to "officially" become their friend. Facebook friending is not always based on offline connections, as you can find and select friends from a list of "People You May Know" (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Options for finding "friends" on Facebook

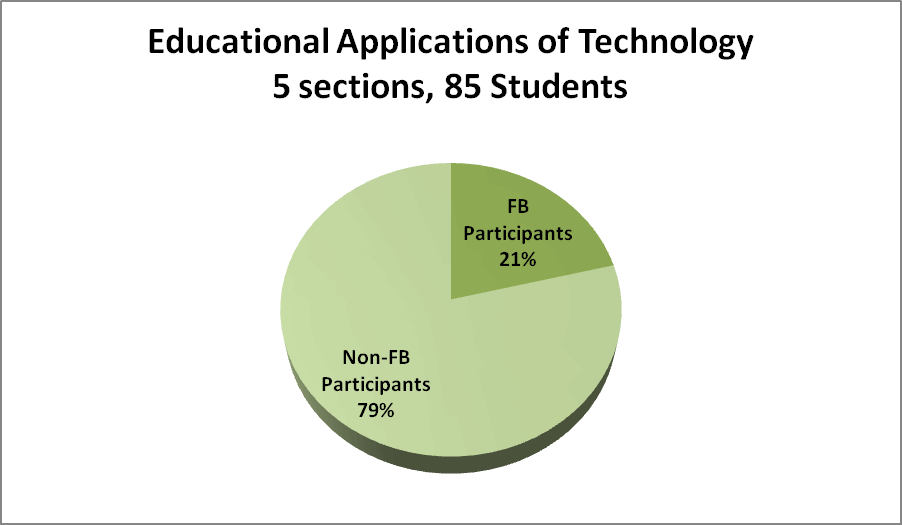

Considering the nature of the Facebook friending process, it is understandable that some students and faculty feel apprehensive when it comes to connecting using this social network. On the other hand, many of my students were more familiar with Facebook than Twitter; it seemed only natural that I use it with my students in the EAT course to send out updates, due date reminders, and special meeting invites. In response to reported student concerns about privacy, I created a "Secret" group for students to join so that membership status and posts would not appear in the EAT students' public timelines (see figure 2). Unfortunately, few students opted to use Facebook (figure 3). Initially I attributed this to my use of a pseudo profile (figure 4), which might have given students the impression that I did not want to friend them, resulting in their not friending me. The low voluntary inclusion rate of Facebook in the course might also suggest that students are simply not eager to mix their social networks with their academic studies.

Figure 2. The Secret group for the EAT course

Figure 3. Participation in Facebook by EAT students

Figure 4. My pseudo profile on Facebook

Twitter and Following

An alternative to friending on Facebook is to follow on Twitter. Twitter does not require students to locate and "friend" faculty, although following may be considered the equivalent.

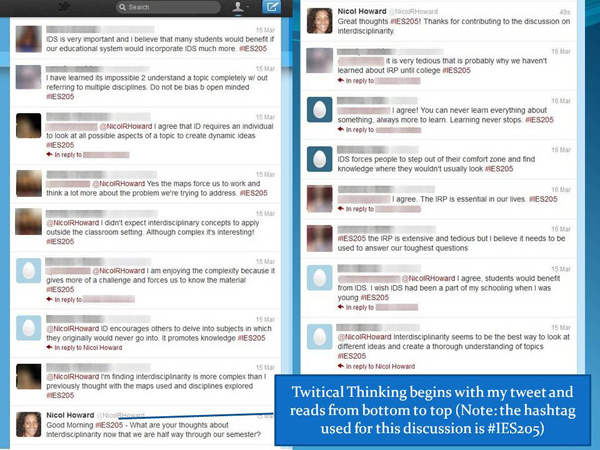

Instructors can use Twitter to send students updates on course materials and deadlines. It can also be used to begin class discussions — what I like to call "Twitical Thinking" — on weekly readings and current events related to course content. My prior experience with allowing optional participation suggested that strongly encouraging participation might work better when implementing social networks in a course.

Instead of giving students the option to use Twitter, an instructor can give them the option to tweet through a classmate's profile by inserting their initials at the end of a tweet. However, doing so will reduce their 140 character limit.

Although students should be strongly encouraged to create their own Twitter profile, I don't recommend requiring that they follow the instructor or course. Instead, a #hashtag at the end of each tweet establishes a timeline and record of weekly discussions. Twitical Thinking begins with a question and #hashtag. Students then respond to questions and their peers' responses, all in a succinct 140 characters or less (see figure 5). They receive instructor responses only when their tweets specifically address the instructor — an effort not to interfere with their choice to communicate directly with a peer instead of faculty.

Figure 5. Twitter discussion that becomes Twitical Thinking

Twitical Thinking discussions can prompt a whole-class discussion on the same or a similar topic. Using Twitter this way allows students to engage in meaningful online discussions on various course topics before, during, or after class. Consistent use of Twitter also establishes this forum as a useful option for students to communicate with peers and/or faculty.

Future Directions

Although my experience argues in favor of using Twitter in class rather than Facebook, both social networking programs remain possible tools to support class discussions, as does the newer Google+.

Facebook with Students

In the future, linking a personal Facebook profile instead of a pseudo profile to a group page might increase student participation in my classes. Incorporating the new Facebook pages that only require students to "Like" the page to receive updates, privately or publicly, might be more effective, as this gives students the option not to friend faculty at all. Students can also post to the Facebook page privately without their own friends seeing that they are posting for a class. Additionally, the use of Facebook does not limit messages to the 140 character limit that applies to Twitter.

Twitter with Students

Students seem to prefer Twitter as the social network used in the classroom; however, it is important to consider that this could result from students not being required to friend or follow faculty. Removal of the pressure to friend or follow is an important consideration when using social networks in the classroom. Hashtags offer a good way to organize, follow, and record class discussions conducted on Twitter without forcing students to follow the instructor or their fellow students.

Google+ with Students

I look forward to implementing additional social networks into future courses to determine the most effective tools and strategies with university students. The next tool for me to consider is Google+, which allows users to create circles and hangouts for students to share resources and engage in private exchanges. For instructors and students, circles allow you to cluster into course-specific groups so that you can disseminate specific information directly to one another. Since users add people to circles to "follow" them, students might feel less concern about connecting with faculty through dedicated circles that can remain private.

What's Next?

Trends in educational technology suggest that the list of social networks available for use in classrooms will continue to increase. Facebook is the current frontrunner, and I believe Twitter is a close second. However, I anticipate the introduction of new tools worth using with university students in the near future and look forward to research on their effectiveness.

- Katherine Karl and Joy V. Peluchette, "'Friending' professors, parents and bosses: A Facebook connection conundrum," Journal of Education for Business, 86 (4), (2011): 214–222.

- M. D. Roblyer, Michelle McDaniel, Marsena Webb, James Herman, and James Vince Witty, "Findings on Facebook in higher education: A comparison of college faculty and student uses and perceptions of social networking sites," The Internet and Higher Education, 13 (3), (2012): 134–140.

- Stephanie Tom Tong, Brandon Van Der Heide, Lindsey Langwell, and Joseph B. Walther, "Too Much of a Good Thing? The Relationship Between Number of Friends and Interpersonal Impressions on Facebook," Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13 (3), (2008): 531–549.

© 2012 Nicol Howard. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article (July 2012) is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.