Patrick R. Lowenthal is an Instructional Designer at Boise State University. Joanna C. Dunlap is Associate Professor and Assistant Director for Teaching Effectiveness at the University of Colorado Denver.

Key Takeaways

- Academics wishing to be seen as thought leaders in their discipline need to be intentional about how, when, and what shows up when someone uses a search engine like Google to search on their name or area(s) of research.

- If Google cannot find a faculty scholar's work or the work of the scholar's colleagues, department, or institution, then it is essentially irrelevant — even nonexistent — because people will not find, read, apply, or build on the work if they cannot locate it via a quick Google search.

- Building a web presence is more than simply having a website and can make the difference in an academic's visibility to the desired audience and opportunities for new projects and collaborations.

Consider an exchange between colleagues:

Professor G: "Remember that article I was waiting to come out? It was finally published. In a top-tier journal, but — after all that time — I don't think very many people will read it as it is already a bit passé. So frustrating… All I wanted to do was get the word out about my research project!"

Professor M: "'Get the word out'? Hmmm… I've been blogging about my research for the last few years, since starting the new project. Good thing I have been because it's led to a number of presentation and collaboration opportunities, and I was recently asked to consult with faculty at another institution. All of my social networking activity is really paying off for me… I think we should talk more about this."

A little over a year ago The Chronicle of Higher Education published a piece titled "Creating Your Web Presence: A Primer for Academics."1 We were excited to see some of the strategies Miriam Posner recommended for academics wanting to create and maintain a web presence. We had been doing many of the things Posner recommended, as well as a number of others. Thus, in many ways this article builds on Posner's piece but argues that faculty should be taking even more steps to build, maintain, and ensure that others can find their presence on the web.

The first step in building a web presence is pretty simple — faculty put their content on the web.2 However, there is more to it than that. Faculty (and academics in general) should think about what they put on the web, where they put it, how they name and structure their content, and finally how they encourage others to read, use, link to, apply, and cite what they put on the web. This second step involves a concept called search engine optimization (SEO).

More organic than paid positioning on a web page, SEO is the process of improving people's ability to locate and access your work online by optimizing the chances your work will come up early and frequently when people do a web search on specific search terms.3 For context, let's look at some results of a simple Google search on each of our names. A search on Patrick's name results in the top 18 links, while a search on Joanna's name results in the top nine links (or top 13 if searching on her nickname, Joni, instead). But all of Patrick's links are relevant and robust: his professional website; Google +, Twitter, and LinkedIn professional profiles; and employment profiles. For Joanna, the results are not as professionally pointed: her university profile; a few manuscripts available via open-access journals and academia.edu; and her personal Facebook profile). Patrick has attended well to SEO, while Joanna has attended minimally to SEO.

The reason it is crucial for scholars to not only have an intentional, purposeful web presence but also to attend to SEO comes down to emerging inquiry behavior. Much of the current literature on web searches points to increasingly higher percentages of scholarly research starting with the web (and often being done completely through resources available on the web), and Google specifically.4 Consider your own inquiry behavior. For example:

- Joanna, recently on two search committees, first looked at the candidates' vitae and then Googled each of them. The results of those searches — not only relevant content but the volume and ease of accessing the content — influenced her thinking about which candidates to interview. The candidates' web presence, aided by SEO, had an effect on the outcomes of the search process.

- Patrick gets Google alerts on "social presence," one of his research interests, each week. His list of articles to read is now being generated by Google more than ever before.

- Joanna was recently contacted by colleagues at another university who had used Google to locate resources related to effective online teaching strategies and had accessed various articles she had authored and co-authored. Through Google, they easily located her contact information, and she has now been retained to consult with them on a grant project. This is a reoccurring event — being tracked via her web presence to collaborate, consult, and guest lecture.

The bottom line is that scholars who want to be seen as thought leaders in their discipline need to be intentional about how, when, and what shows up when someone uses a search engine like Google to search on their name or area(s) of research. When was the last time you Googled yourself or your area(s) of research? What did you find? Or, more importantly, what didn't you find that you should have?

Increasingly, we work in a "Google World."5 What this means in practice is that if Google (or other popular search engines) cannot find your work or the work of your colleagues, department, or institution, then it is essentially irrelevant — dare we say, nonexistent — because people will not find, read, apply, or build on the work if they cannot locate it via a quick Google search.6

Happily, some basic strategies for effectively addressing SEO needs are easily applied when establishing and maintaining web presence. We will describe how 10 strategies can help scholars realize their web-presence goals and better connect with their colleagues and audience all over the world.

Creating a Web Presence with SEO

Whether you are a scholar yourself or in a position supporting faculty at an institution of higher education, we suggest the following 10 strategies for scholars to create a strong, professional web presence.

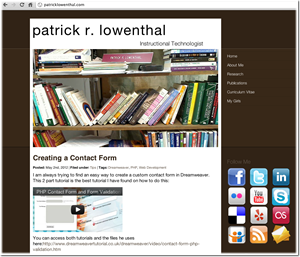

1. Get a professional website.

While you might have a web page on your institution's website that lists your area of expertise, CV, and possibly even information about courses taught or recent publications, we believe academics need to get their own professional website — ideally with a specific domain name. Whenever possible, the domain name should consist of the academic's full name (e.g., www.patricklowenthal.com). This isn't nearly as difficult as you might think. For instance, you can set up a free website with Google Sites — which you can set up and edit yourself without the help of a web developer — and add a personalized domain name to it for about $10 a year (see the following two videos on how to do just this).

Video 1: Create a Personal Website with Google Sites in Minutes

Video 2: Add a Personal Domain Name to a Google Site

Some of the benefits of having a professional website (in addition to whatever efforts your employer might take to advertise and promote your work) are that it:

- Establishes one central place to host and promote all of your scholarship.

- Creates a consistent web presence regardless of job changes or university website redesigns (and URL changes).

- Drives traffic to your site rather than solely to a university's website (though ideally you are linking to your university pages from your professional website and vice versa).

- Increases options to create additional content (e.g., blogging).

- Provides easy methods to track visitors (i.e., track the number of people who are interested in your work).

- Gives you more control over what and when content is placed on the web (rather than waiting for someone to update your university's page).

- Increases your search engine ranking.

2. Regularly update your professional website.

Having your own professional website is just the first step. You need to take time to update it regularly. This isn't as hard as it sounds, but it does take some dedication. Simply put, new content can help increase your search engine ranking.7 How often you update your website is up to you, but you will typically find that the more you update it, the more visitors you are likely to get, which can help increase your search engine ranking. The following are just a few ways you can do this:

2a. Maintain a blog. Whether you update it daily, weekly, or just monthly, a blog can provide an easy place to share with others (and especially Google and other search engines) what you have been up to. In our field of Instructional Design and Technology, here are a few different examples of scholars who blog:

- Michael Barbour: http://virtualschooling.wordpress.com/

- Scott McLeod: http://scottmcleod.net/

- George Siemens: http://www.elearnspace.org/blog/

- Lisa Dawley: http://lisadawley.wordpress.com/

- George Veletsianos: http://www.veletsianos.com/

- Alec Couros: http://educationaltechnology.ca/couros/

Related, consider establishing a research-specific blog (or website, for that matter) to keep interested colleagues updated on your work — as well as the work of others — within a specific research topic or project. Communitiesofinquiry.com is an example of this. (Note: This could also entail creating a wiki about your research in which you invite others to take part in adding content.) You can also maintain a blog on teaching strategies within your discipline; for example, Joanna maintained a blog on postsecondary (online and in classroom) teaching strategies for a few years (see http://thoughtsonteaching-jdunlap.blogspot.com/) that led to several collegial connections and collaborative opportunities.

2b. Post manuscripts online. If you accept the premise that more and more people are turning to Google to conduct research, then it makes sense to put all of your manuscripts online. While a number of websites let you upload and share your publications, you ideally want to post all of your manuscripts (in some form or another) on your own professional website (in addition to any other places you share them). The following scholars have done this well over the years:

- Susan Herring: http://www.slis.indiana.edu/faculty/herring/pubs.html

- Brent Wilson: http://carbon.ucdenver.edu/~bwilson/

It is a good idea to check on a journal's copyright policy before uploading any final versions of your work. However, most of the time, you can post a pre-print of a manuscript or an earlier version that you might have presented at a conference. The key is to simply note on the preprint or conference paper where people can find the final published version and how to appropriately cite the paper. The bottom line is that when a person goes looking for your research, you want to eliminate as many barriers as possible to finding it. Further, some professionals out there might benefit from your scholarship but can't find it because they lack easy access to a university library. Thus, there are multiple reasons to post your work online.

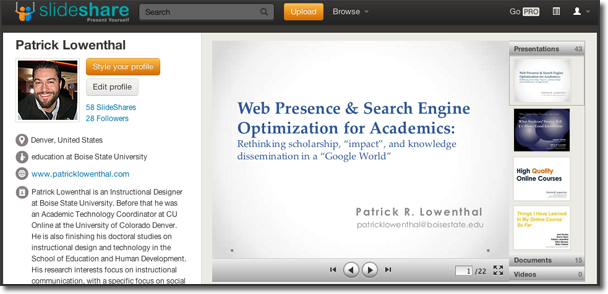

2c. Post presentations online. Another strategy to improve your SEO and ultimately your search engine ranking is to upload and share all of your presentations. While we recommend uploading both the presentation and the paper in progress (if applicable) to your professional website, even simply uploading the presentation alone (which summarizes your research) can help improve your search engine ranking by establishing you as a researcher of "X" — whatever "X" might be. While you can easily upload your presentations to your professional website, we also recommend uploading them to a presentation sharing site like SlideShare; we elaborate on this later in the article.

2d. Post teaching materials online. We recognize and value the scholarship of teaching.8 Whether you focus primarily on teaching or on research, we believe faculty would be better off sharing their teaching materials with the world — especially when teaching classes related to their research. Posting teaching materials online is another way of adding content to your professional website and thus increasing your search engine ranking while establishing your expertise and credibility in a given subject matter.9

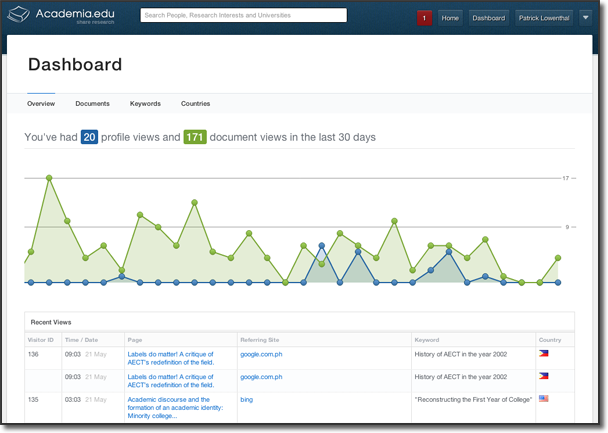

3. Track your traffic.

If you create a web presence, you need to attend to the effectiveness of your strategies and adjust them to strengthen your SEO. This goes beyond a typical "hit" counter. What you want to know is what people are looking for and at, so you can adjust to make it easier for people to find you and your content and at times create more of the type of content that others find beneficial.

3a. Review analytics. Once you create a professional website, you then need to use a tool like Google Analytics to track how many visitors you are getting to your website, what content they are accessing, and any relationships between the content you post and the frequency of visitors. Once you start tracking this, you will likely find a strong relationship between the number of views your website gets and the frequency with which you post new content. Further, and more importantly (especially if you blog infrequently), you might begin to notice which posts attract more viewers and therefore get a better idea of what your audience values.

Video 3: Adding Google Analytics to a Google Site

3b. Set up Google alerts. A good SEO strategy should also focus on what others post online related to you, your publications, and your research in general. Google makes it easy to set up alerts that notify you when new content is posted on the web. We recommend that you create a Google alert for your name (and different iterations of it; for example, Joanna is "known" on the web as Joanna Dunlap, Joanna C. Dunlap, J. Dunlap, J. C. Dunlap, and Joni Dunlap, so she has Google alerts set up for each iteration). This will allow you to be aware when people are writing about you in academic journals and conference proceedings, on blogs, or on social networking sites. Knowing the number of times you are cited online helps you gauge your influence as a thought leader.

In addition, depending on the functionality of the site where you are being referenced, you may have the opportunity to comment, clarify, and share additional work by contributing to the conversation around the reference. For example, on more than one occasion Patrick has received an alert related to his research in response to which he went to the website in question and posted a comment to share additional views and point the group to another one of his publications on the topic.

Tracking how often your name is referenced is only one approach. We also recommend:

- Create a Google alert for each article you publish so that you can find out who is citing and using your work. This can provide opportunities to collaborate with others as well as ways to help you document the "impact" of your work. Searching by the title of the article will help you identify instances where people are discussing your work but not properly attributing you as the author.

- Create a Google alert for specific keywords related to your research. This helps you stay on top of each new study published in your area (which you could always blog about which would in turn help improve your search engine ranking for those keywords). While we still recommend conducting more traditional searches using your library's databases (in addition to any Google searches you might conduct), we have found that Google alerts on specific keywords helps us stay connected and grounded in the current literature of our field.

It is important to note that the power of Google alerts is not just in finding information but also in the opportunity to connect with more people and extend the dialogue about your scholarship and theirs.

4. Publish work in open-access journals.

Faculty often feel pressure to publish in a select number of tier-one journals. There has been great debate on how to assess the impact of a journal. While in the short run it might not help with tenure and promotion (if you work at an institution that does not value open-access journals), we believe that all faculty should publish at least some of their work (especially work that builds upon previous research they have conducted) in open-access journals.10 Open-access journals are "open" and therefore make it easier for others (including Google) to find, read, and share your work. For instance, we have published a number of articles in open-access journals. We have been delighted to see the "read" count grow over time.

| Open Access Article | "Read" Counts* |

|---|---|

| Dunlap, J., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2010). "Defeating the Kobayashi Maru: Supporting Student Retention by Balancing the Needs of the Many and the One." EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 33(4). | 1,427 |

| Lowenthal, P. R., & Thomas, D. (2010). "Death to the Digital Dropbox: Rethinking Student Privacy and Public Performance. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 33 (3). | 6,195 |

| Dunlap, J. C., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2009). Horton Hears a Tweet." EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 32 (4). | 7,049 |

*Note: These "read" counts were accurate as of 5/23/2012.

However, not all open-access journals are created equal. We recommend focusing on ones that have high readership, are well respected, and allow you to identify the number of times people have "read" your article. If you are unsure as to which open-access journals are appropriate for you to publish in, check with your colleagues, professional associations, and your institution's library staff.

5. Publish your work via social media sharing sites.

Faculty often produce work of value not only to the local community (e.g., the university) but also to the greater professional community of practice. However, the work may not be developed to the caliber necessary for formal publication. These materials — such as white papers, application recommendations, program evaluations, reports of pilot studies, teaching materials, creative works, and the like — may be shared online via social media sharing sites. Social media sharing sites offer an opportunity to further share your expertise with a wider audience.

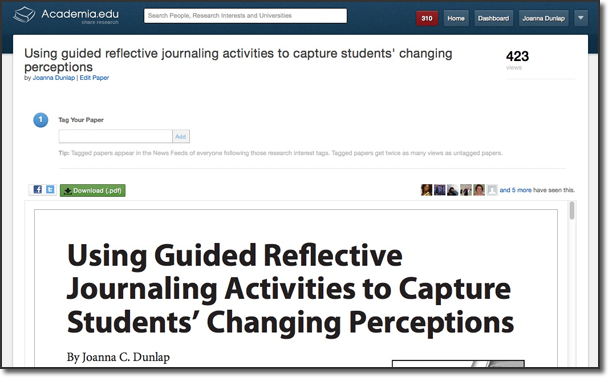

5a. Manuscripts. A growing number of online reference managers and academic social networks let you make your work available to a targeted audience; these are a few of the more popular sites at the moment:

Some of these sites focus more on the reference manager side of things, while others focus more on the social network side of things. However, they each — to varying degrees — provide a venue where faculty can set up a profile (which should include a link back to his or her professional website) and share details on papers presented at conferences or published in journals or books. We recommend joining as many of these as you can. The key is to update these sites each time you present or publish something new. Each site offers unique features and tools. For instance, you can set up an account on Academia that sends you notifications each time a person searches for you or your work.

Academia also allows you to track how many times people have viewed your work.

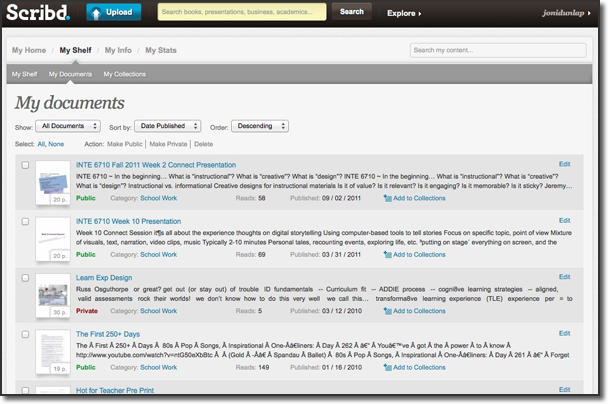

Document repositories not specific to academia are useful in getting your work out there. We often use Scribd.com, for example, as another way of making manuscripts available online. In addition, be sure to check with your institution's library to find out what they might be doing in this area as well. (For instance, Boise State University is using ScholarWorks and Selected Works to promote faculty scholarship.)

5b. Presentations. Besides posting your course and conference presentations to your professional website, post them on presentation repository sites such as SlideShare and Slideboom. People use these two sites to search for presentations on specific topics, plus they are tagged for Google search referencing. Sites like SlideShare offer the following benefits:

- Shows total number of views

- Allows others to find, share, and use (and possibly reuse) your work (who might not have found your work on your own website)

- Provides a centralized place to search for presentations

- Results in higher search engine ranking due to a large user base

- Provides an easy URL to provide to users to find your presentations (e.g., www.slideshare.net/plowenthal); thus, rather than directing users to one presentation, you are sharing your library of work with them

In addition, uploading your course and conference slides to a site like SlideShare helps you establish a new place on the web for people to find you. So while traditional SEO focuses on driving users to one website, scholars need to think more about how they can drive users to their content, whether that content is located on their professional website or on a third-party site.

5c. Teaching materials. Faculty also spend quite a lot of time producing teaching materials. Faculty who share their teaching materials beyond their courses and programs demonstrate their content expertise while sharing valuable resources with the community of practice. Plus, it is yet another way to establish online presence and credibility — the quality, quantity, and variety of content you put on the web helps drive more people to your website. Besides publishing your teaching materials on your website, there are established repository sites, such as MERLOT, that organize materials by discipline, grade level, and type. In addition, if you produce videos and presentations for your courses, you can also share those via YouTube, Slideshare, and similar sites.

6. Leverage social networks.

Researching social media over the years, we have found — among other things — that different disciplines tend to use different social networking sites.11 We have also found that while some people like certain social networking sites, others detest them. Like it or not, social media is a great way to increase your search engine ranking and share your work with others. Whether Facebook, Twitter, and/or LinkedIn, consider how you can leverage these sites to share your work with others. For instance, each time you add new content to your website, consider tweeting about it so that others are aware of your new work.12

Social networking sites are a great way to get your name out in the professional community of practice in a more informal way than publications. For general professional connections, we use Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook; several of our professional organizations have a presence on all of these social networks. We also participate in discipline-specific social networks (for us, this includes the Listserv IT Forum). Through these social-network connections, we are able to engage in relevant discussions of problems of practice and share our expertise and current work with other practitioners and faculty in our field while at the same time learning a great deal from others.

7. Be a good user of others' content.

Similar to participating in social networks, another way to enhance SEO and web presence while sharing your expertise and providing value to the professional community of practice is by scanning and commenting on others' contributions:

- Review others' work. For example, you can write reviews of the books you use in your courses for Amazon and other online book resellers.

- Contribute content to other sites. For example, you can contribute content to professionally relevant Wikipedia pages and professional blogs that allow and encourage sharing and collaboration.

- Organize professional resources into an open accessible repository. For example, you can develop resource (i.e., articles, websites, videos, and so on) repositories for your research and/or teaching domain using social bookmarking sites such as Delicious.com.

8. Complete all profiles.

If you are like us, you have dozens of different web-based accounts. Many of them enable you to complete a "profile" about yourself. When appropriate, complete the profile and include such things as keywords to your research, specifics on your research, and — at minimum — a link to your professional website. You might also link to specific publications or presentations you consider relevant. The following are a few general accounts that have profiles you can complete:

- Google+

- Academia

- Mendley

- YouTube

- SlideShare

- Microsoft Academic Search

- Google Scholar

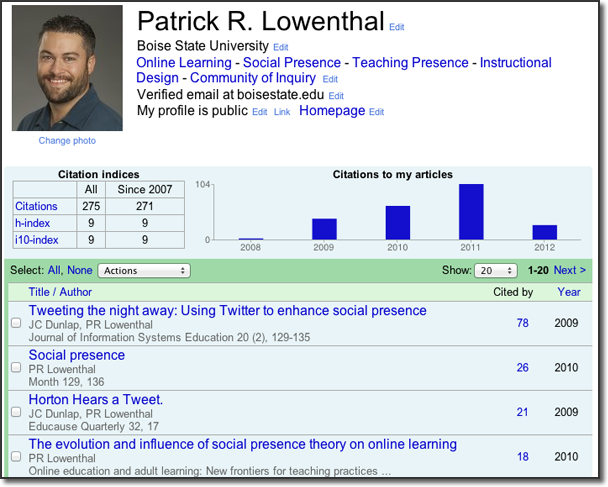

You should pay specific attention to Google Scholar's new profile, which actually lists all of your work. The following is an example of what a Google Scholar Profile looks like:

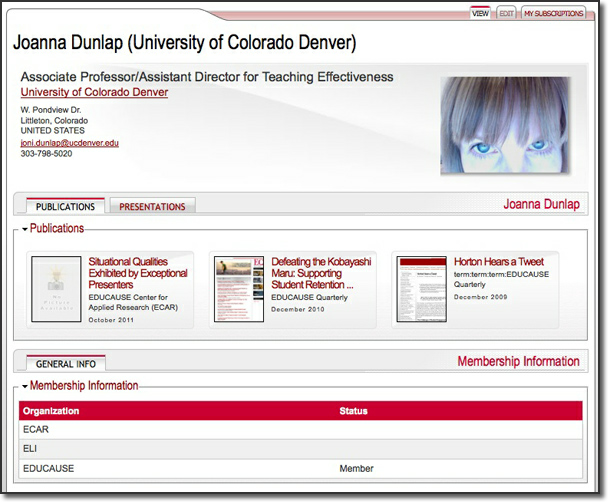

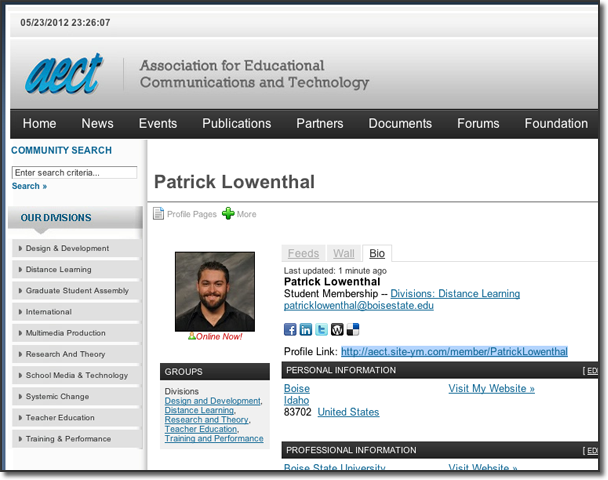

In addition to general accounts, we also spend time completing (and at times continually updating) our profiles on discipline-specific websites (e.g., AECT, EDUCAUSE).

9. Think about how you name papers, presentations, and web pages.

Over the years, we have had a lot of fun finding creative names for papers we've published. For instance, "Defeating the Kobayashi Maru: Supporting Student Retention by Balancing the Needs of the Many and the One" and "Hot for Teacher: Using Digital Music to Enhance Students' Experience in Online Courses" are two of our favorites. We have begun to question, though, whether we should spend more time focusing on creating "googable" keyword-driven titles (as boring as that may sound). Take, for instance, the following two articles:

- "Horton Hears a Tweet," EDUCAUSE Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 4 (2009)

- "Tweeting the Night Away: Using Twitter to Enhance Social Presence," Journal of Information Systems Education, vol. 20, no. 2 (2009), pp. 129–136

While the first one is creative and fun and even published in an open-access journal, the second one, published just a few months earlier in a subscription-based journal, has been cited almost three times as often.13 Our theory is that this is due in part to the fact that one of them has a good googlable key word, "Twitter," whereas the other one does not.

SEO experts spend a good amount of time thinking about things that most academics do not, such as the best way to name files on the web, the best way to use headings and keywords to improve SEO, and the best way to use metadata to ultimately improve search engine ranking (e.g., Did you know that you can add metadata to a PDF or keywords to a word document?). We are not SEO experts, and we do not expect other faculty to be. Simply put, faculty need to think about how they name their articles and the best way to include key words in their titles. In addition, faculty should add meta-data to any web pages, documents, or PDFs they put on the web.14

10. Promote new presentations and publications.

Finally, in addition to "pull" types of strategies where you strive to help pull users to your content (likely through the use of Google), there are other types of "push" strategies where you can help push news about conference presentations and/or publications, which can in turn help improve your search engine ranking. The following are just two push strategies we recommend.

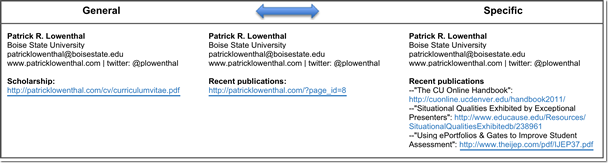

- Add a line to your e-mail signature where you list your most recent publications (and even better, add a URL to the publications). This makes it easy for others to quickly click on and view your work. The following are three different ways you might accomplish this, from general to specific:

- Submit news of publications through any appropriate department, school, or college Listservs or newsletters.

- Blog and tweet about any new publications.

Conclusion

Faculty are in the knowledge creation business. Whether demonstrated through their research, teaching, or both, they are subject-matter experts. Therefore, search engines (especially Google) should be aware of who they are, what they do, and how they contribute value. To this end, SEO is a critical consideration, and faculty must attend to it when establishing and maintaining a web presence that showcases and shares their expertise with the world.

We recognize that SEO is a complex subject, so much so that there are consultants available to help organizations and individuals improve their search engine rankings. Nevertheless, the strategies described here are relatively straightforward to implement without hired consultation. These strategies help people find you and your work, and give you more control over your web presence so that you consistently look your best on the web.

- See Miriam Posner's guest post, "Creating Your Web Presence: A Primer for Academics," Chronicle of Higher Education (February 14, 2011).

- Through supporting faculty who teach online, we have found that many faculty are uncomfortable putting their content on the web — whether because of their fear that they will lose their intellectual property, increase plagiarism or cheating in their courses, or simply not having complete control over their work. Therefore, this first step to developing a web presence — putting content on the web — is difficult for many faculty.

- For more on search engine optimization see "Search Engine Optimization," Wikipedia; "Search Engine Optimization," Google's Webmaster Tools; and "Google: Search Engine Optimization Starter Guide."

- For more on people's search behaviors and Google's dominance, see "Web search behavior of university students: A case study at University of the Punjab," Webology, vol. 6, no. 2 (June 2009); Ian Rowlands et al., "The Google generation: The information behavior of the researcher of the future" (2008); Bradley M. Hemminger, Dihui Lu, K.T.L. Vaughan, and Stephanie J. Adams, "Information Seeking Behavior of Academic Scientists," Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 58, no. 14 (2007), pp. 2205–2225; Jillian R. Griffiths and Peter Brophy, "Student Searching Behavior and the Web: Use of Academic Resources and Google," Library Trends, vol. 53, no. 4 (Spring 2005), pp. 539–554; Kristen Purcell, Joanna Brenner, and Lee Rainie, "Search Engine Use 2012," Pew Internet & American Life Project (March 9, 2012). It is important to note that we do not necessarily think people's heavy reliance on a simple Internet search to find all of their answers is a good thing, but it is a reality. See "Is Google Making Us Stupid?" by Nicholas Carr, The Atlantic (July/August 2008) for an interesting discussion on what the internet is "doing" to our brains.

- Purcell, Brenner, and Rainie, "Search Engine Use 2012."

- We hope over time that this changes and that people begin to develop better information literacy skills. However, all signs seem to suggest the contrary. As people find themselves doing more with less time while information continues to grow exponentially, we suspect that people will continue to rely more and more on search engines like Google to filter results and provide the answers they seek.

- SEO experts like to debate just how much new content is needed and how frequently it is needed to help improve a site's search engine ranking. Conventional wisdom is that quality content is more important than quantity, so avoid the urge to simply post unrelated information daily in an effort to boost your search engine ranking.

- For more on the scholarship of teaching and learning see The International Society of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, as well as the Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning and the International Journal for Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.

- While the focus of this article is on developing a web presence and promoting one's own work, we strongly believe in sharing educational resources even when there is no perceived self-benefit. Sharing educational resources is not a new idea. However, as the open education/open educational resources movement gains traction with recent press on popular Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) like Curtis Bonk's (see "4 reasons why the Bonk MOOC is so interesting") and free online courses from "elite" universities (see "Harvard and M.I.T. team up to offer free online courses"), we hope that sharing educational resources becomes commonplace in the future.

- Michael Stratford's recent piece in the Chronicle actually warns against what he refers to as "predatory" online journals, but we are suggesting publishing in a variety of outlets (e.g., open access and subscription, refereed and edited, research-focused and practitioner-oriented) in order to get the word out there about your work; there are several reputable, high-quality online journals, often supporting professional organizations and conferences.

- See Joanna C. Dunlap and Patrick R. Lowenthal, "Tweeting the Night Away: Using Twitter to Enhance Social Presence," Journal of Information Systems Education, vol. 20, no. 2 (2009), pp. 129–136; Joanna C. Dunlap and Patrick R. Lowenthal, "Horton Hears a Tweet," EDUCAUSE Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 4; and Patrick R. Lowenthal and Joanna C. Dunlap, "Investigating students' perceptions of various instructional strategies to establish social presence," paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans.

- See Gunther Eysenbach, "Can tweets predict citations? Metrics of social impact based on Twitter and correlation with traditional metrics of scientific impact," Journal of Medical Internet Research, vol. 13, no. 4 (2011).

- While "Horton Hears a Tweet" might not be cited as much as "Tweeting the Night Away: Using Twitter to Enhance Social Presence," it has been "read" 7,038 times, which is likely more than all of our subscription-based manuscripts combined have been read. Further, it is possible that faculty are simply relying on the reference lists of others more than Google when conducting their literature reviews. In other words, we contend that as a manuscript begins to be cited frequently, it is likely that it will continue to be cited by others.

- If you hope to use Google Analytics to track the number of views of your work on your personal website, you should consider creating a blog post or HTML "splash" page that describes the work (possibly even including keywords, an abstract or description, and a link to the document or PDF) because Google Analytics does not easily track direct links to PDFs or documents. Here is an example of a splash page: http://patricklowenthal.com/labels-do-matter-a-critique-of-aects-redefinition-of-the-field/.

© 2012 Patrick R. Lowenthal and Joanna C. Dunlap. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 license.