Key Takeaways

- Integrating mobile learning games into a graduate-level course at Appalachian State University built on the concepts behind constructionist pedagogy and service-learning.

- Students constructed mobile learning games related to aspects of local wetlands education by partnering with the community and faculty experts.

- The project not only increased students' interest in community service, it also prompted a strong positive reaction to different types of collaboration.

This article describes a project integrating mobile learning games into my course at Appalachian State University, in collaboration with a community partner and for the community as a whole. My interest in mobile learning began over 10 years ago, when I worked in an IT consulting company designing mobile applications. At that time, just at the end of the dot-com era, there was a lot of talk about mobile services providing "anytime, anywhere" access to...well, just about everything, including educational content. The dream was, and perhaps still is, that mobile computing will provide ubiquitous access to knowledge, information, and educational content. Even back then, I began to wonder, who will build it? Through experiences in integrating mobile learning into courses over the past few years, I have come to believe that the answer to that question is — all of us.

The process of constructing educational mobile games can be as beneficial as the act of playing. Therefore, my beliefs about integrating mobile learning into my courses lean toward constructionist pedagogy and experiential learning. Furthermore, community engagement through service-learning can help link course content to the needs of both the local and global communities. This article provides an overview and assessment of an experiential learning project that involved student groups from my course at Appalachian State University collaborating with a community partner to develop mobile games related to aspects of local wetlands education.

Reflections on Place-Based Game Design

In 2007, the year the iPhone was released and the Android mobile platform unveiled, I had just received a grant from the U.S. Geological Survey to develop mobile game experiences to educate youth on Guam about threats to the island's groundwater. In researching the topic, I discovered that in addition to students, very few teachers understood core concepts about groundwater, one of the world's most vital natural resources. One way to address the problem with both populations was to recruit a group of public school teachers to create a groundwater mobile learning game. In that way, they would have to research and understand the topic and issues. My thinking followed the old adage "The best way to learn something is to teach it to someone else."

The game that the teachers developed, Groundwater Survivor, 1 took the form of a mystery where players shipwrecked on a tropical island had to work in groups of two or three to find a source of fresh drinking water. The game space was located in an open field on the University of Guam campus and tested with local middle school students (Figure 1). Players gained water (points) by finding the best fresh water sources, but lost water for each step taken. Players had to investigate possible sources of water, read about the contamination threats, and debate within their group the best source of potable water before making a move. The game was developed using the Wherigo mobile platform and tested using both Garmin Colorado GPS handsets and HP iPAQ Pocket PC devices.

Figure 1. Middle School Students on Guam Playing Groundwater Survivor

I have since reflected on the model I use for incorporating mobile learning games into courses and now believe that these learning experiences should be:

- Created by students and teachers. Of course, there is value in professionally developed games for education, yet I noticed that the teachers who created the game learned more about groundwater concepts than did the students who played it.

- Developed on simple platforms. For mobile games to be developed by all requires simple, easy-to-use platforms that allow a game to be tested quickly and easily.

- Available for popular mobile services. To target the greatest number of players, a mobile game should be available on popular mobile hardware platforms like Apple iOS and Android.

- Place-based and developed for and with the community. One of the reactions most strongly expressed by teachers developing the Groundwater Survivor game was appreciation that it addressed a real environmental issue threatening the quality of life on the island. This connection to the greater community, through both formal and informal learning experiences, can be addressed through the construction of place-based mobile learning games.

Theoretical Underpinning: Experiential Learning

Following the Groundwater Survivor project, I began to investigate constructing mobile place-based games as an instructional model. Within the past two years I have also begun to incorporate service-learning experiences in my courses. Constructionism and service-learning have become core concepts of my model for integrating mobile learning into education.

Constructing Mobile Games as an Instructional Strategy

Constructionist learning theory holds that learning is most effective when students are engaged in making or constructing objects and artifacts.2 Yasmin Kafai discussed two perspectives related to educational games: instructionists focus on the design of games for the purpose of instruction, and constructionists believe in providing opportunities for students to construct knowledge through the making of games. She pointed out that "fewer people have sought to turn the tables: by making games for learning instead of playing games for learning."3

The continuing emphasis on the instructionist paradigm for mobile learning games is evident in many of the examples presented in the Horizon Report, an influential annual publication outlining the potential impact of emerging technologies in teaching and learning. Of the six "technologies to watch" included in the latest Horizon Report,4 half relate directly to mobile place-based learning games: mobiles, augmented reality, and game-based learning. However, few of the examples outlining the technologies in practice focus on students constructing mobile learning applications, games, or augmented reality experiences.

Collaboration with the Community through Service-Learning

Service-learning is an experiential learning strategy that seeks to integrate classroom instruction with community service.5 This model encourages students to apply what they learn in the classroom to address issues in their community and to further their learning through reflection on the service component. Service-learning experiences are expected to benefit both the student and the community, giving students the opportunity to learn and apply academic skills, enhance their personal growth, and develop a sense of civic and social responsibility. The community benefits from the volunteer work that the students provide.

Service-learning and constructionism incorporate Dewey's belief that learning results from the interaction of knowledge and skills with experience.6 They are thus complementary models for engaging students in discovering knowledge firsthand.

Community Collaboration on Wetlands Mobile Games

Students in a section of my graduate-level introductory course in instructional technology at Appalachian State University worked on a collaborative project involving the design and development of place-based mobile games related to environmental education. The primary goal was to engage students in exploring the role of mobile technologies in instructional settings, but I also wanted to assess the impact of collaboration with a community partner, in a service-learning experience, on the students' perceptions of their role in the community and their attitudes toward local environmental concerns.

In the spring 2011 semester students in my course partnered with the Watauga River Conservation Partners, a local community organization working to protect the Watauga River. Student groups received on-site tours, supplementary educational materials, and advice on possible wetlands game ideas from the organization during the construction of mobile learning games. By the end of the semester, these games were available for the community to play on mobile phones and tablet devices at a wetlands area adjacent to the Boone Greenway Trail, a popular recreation area in town (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. The Boone Greenway

Figure 3. An Educational Sign in the Wetlands Area of the Boone Greenway

Marc Prensky7 outlined a model of "mini-games" (or "casual" games) that are about a single subject and take less than one hour to play. They can be developed in small student-led teams, with students conducting their own research to develop a game within two months. A mini-game can be combined with others, each focusing on one unit or component of the curriculum, to resemble "complex games," which cover a broad subject.8 Over the semester of my course, which incorporated the mini-games model, student groups each designed and built a place-based learning game for middle school–aged children, with each game related to one aspect of wetlands education. Throughout the semester, students individually posted to a blog to reflect on aspects of game design and their service component. They also wrote a reflective essay at the end of the course about the game development process.

Mobile Platforms for Building Place-Based Games

Students in my course investigated and tested three mobile game platforms in the design and construction of place-based learning games. We focused on these three because they are widely available on common mobile hardware platforms and are easy to use, from both the user (player) and developer perspectives.

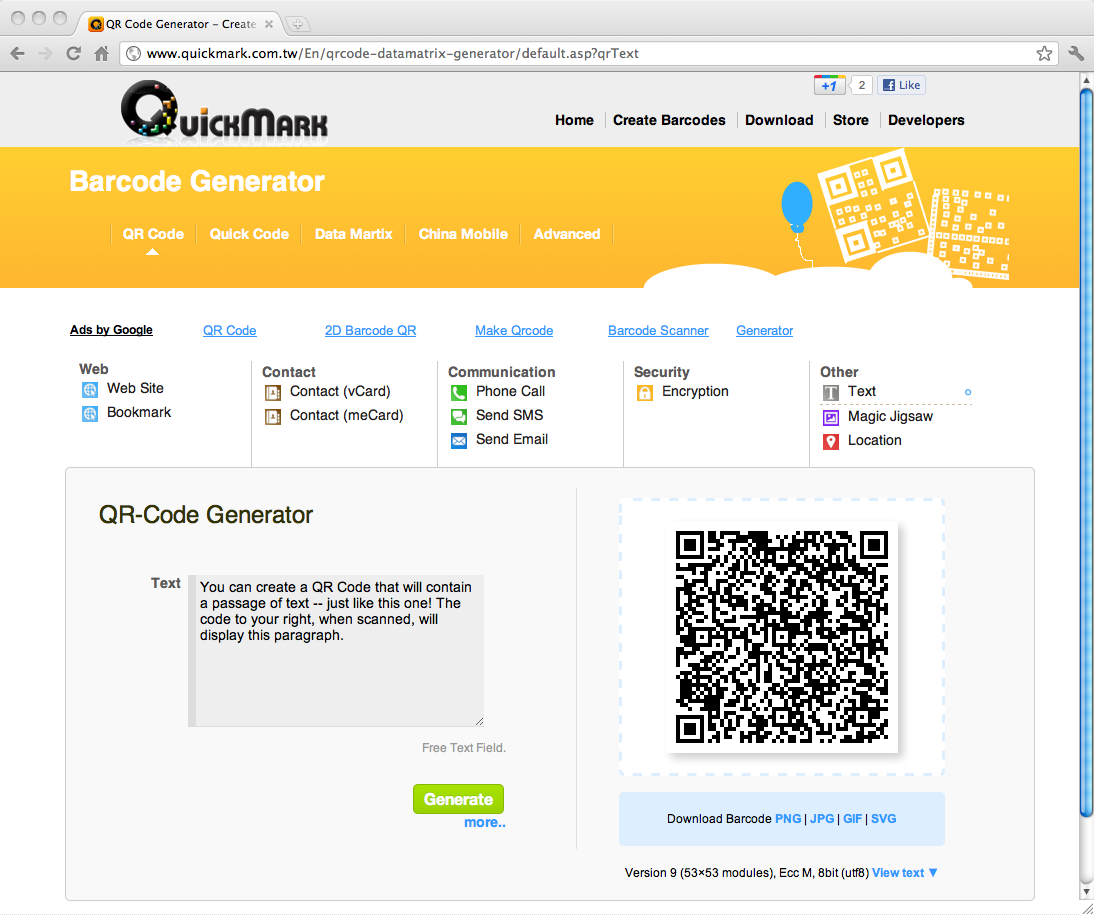

Tagging with QR Codes

The Quick Response or QR code is a type of bar code that can be quickly read by a mobile phone camera and interpreted by a QR reader software application (app) on the device. QR codes can be used to open a web page in the user's handset, send a text message, dial a phone number, add a vCard to the user's list of contacts, or display a string of text. Figure 4 shows a QR code that opens a web page.

Figure 4. QR Code for the Home Page of Appalachian State University

QR codes are a simple way of "tagging" objects in the physical world. They are easily used in mobile learning games, by printing them on stickers and then placing them permanently on objects, or by putting them on index cards for temporary tagging at a location. It is an open standard, so QR codes can be generated easily at a number of websites.

One advantage of designing mobile games with QR codes is that they work with non-smartphone and older handheld devices lacking a GPS but having a camera. In addition, since QR codes do not require satellite positioning to locate game objects or entities, the QR code technology can be used to create games for indoor spaces, like museums and school buildings. On the other hand, a drawback for use in mobile games is that QR code actions are limited.

In class we use the QR code reader QuickMark, which is available at no charge for most popular mobile platforms, such as Android, Apple iOS, Symbian, and Windows Mobile. Codes can be generated for free through the web-based system on their site (Figure 5), with options for print size and download images. This application has several advantages over other QR code generators and readers that can assist with designing mobile games. Encryption, for example, requires the game player to input a key (a word or phrase) before accessing the text content of the coded object. This could be used in a game to require players to answer a question before moving on to the next level of game play. The "magic jigsaw" encodes an image in a series of QR codes, requiring the player to scan each code in the correct order to reveal the image.

Figure 5. The QuickMark Website for Generating QR Codes

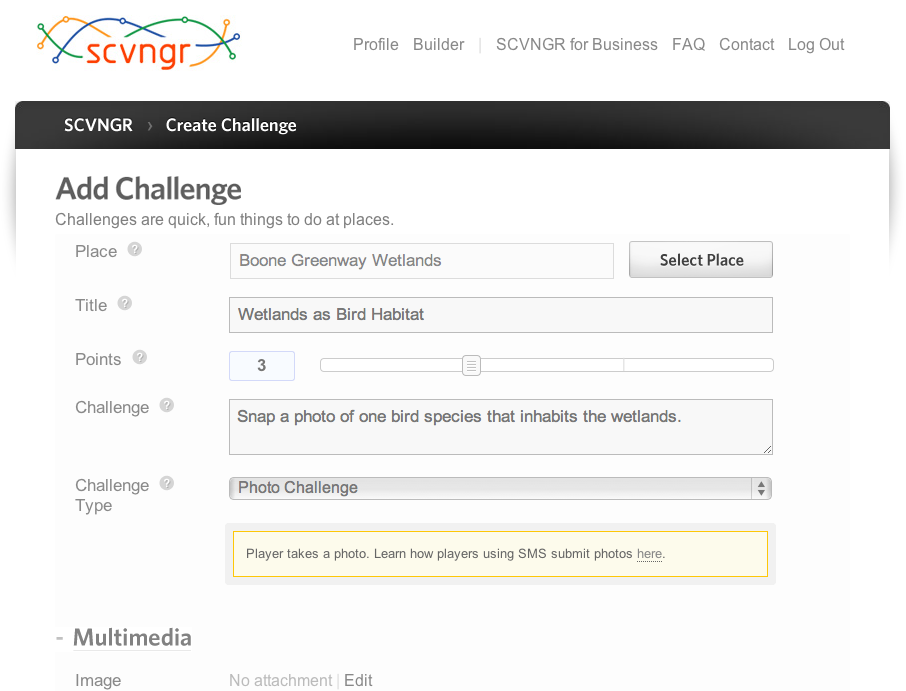

Social Scavenger Hunts with SCVNGR

There are many social scavenger hunt applications available for mobile handsets. One of the most popular location-based scavenger hunt games, geocaching, focuses on hidden containers called geocaches that are placed outdoors for people to find. The geocaching website boasts over one million active geocaches around the world.9

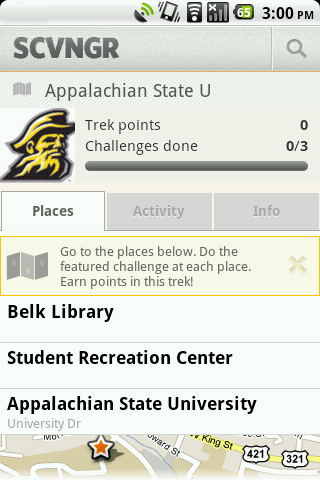

Another social scavenger hunt, SCVNGR, is becoming popular in the United States. This service uses the GPS in the player's mobile device to present challenges on the screen at specified physical locations. These challenges can be enhanced with audio, image, and video content. Stringing together challenges into "treks" can create mini-games in which players can win points by completing a challenge. The types of actions asked of a player at a challenge point include taking a photo, scanning a QR code, or answering a question with either a specific or an open-ended text response.

Students in my course could, for instance, use the photo capture challenge to have players identify and take a photo of one species of bird in the wetlands habitat. Community-building and communication features of SCVNGR allow groups of players to collaborate by using text messaging or by linking communication to social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook.

Figure 6 shows the builder interface on the SCVNGR website. The builder interface is entirely web-based, robust, and easy to use. After creating an account, users can begin to design challenges, treks, and rewards, although they are limited to a total of five active game elements in the basic (free) account. The site offers very good video tutorials to help students get started building in SCVNGR.

Figure 6. The SCVNGR Builder Interface for Designing a New Challenge

The SCVNGR player app is available for free on Apple iOS and Android platforms (Figure 7). However, it does require an up-to-date smartphone to use — for instance, Android 2.1 or iOS 3.1 or later. This could be a problem in situations with a mix of smart- and non-smartphones or different generations of smartphone devices in a player population.

Figure 7. The SCVNGR Player App Showing a List of Treks

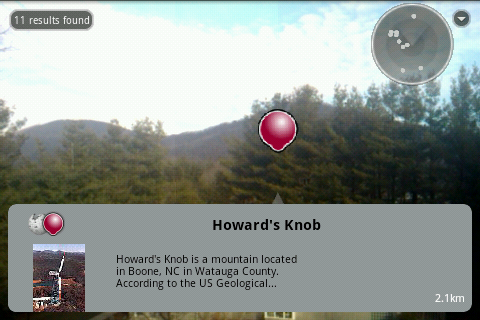

Augmented Reality

The 2011 Horizon Report includes augmented reality (AR) in the technologies to watch for in education within the next two to three years. The report defines AR as a "layering of information over a view or representation of the normal world."10 This definition could include QR codes and SCVNGR, as they both add information to locations and objects in the normal world.

For categorizing mobile services, AR apps are generally those that use the phone's video camera input to allow the overlay of digital information (text, images, 3D objects, etc.) on the display. In other words, as a player scans her phone across the horizon, she can see both the normal world, from the camera input, and the augmented world, presented as point-of-interest (POI) markers, digital photos, objects, or other media types. Figure 8 shows the Wikipedia World layer in a mobile AR viewer app (often called a browser), displaying Wikipedia entries in the vicinity of the user's location.

Figure 8. Wikipedia Content Layered over the Phone's Live Video Camera Feed

Several popular apps for mobile devices allow exploring AR for mobile learning; two of the best known are Wikitude and Layar. Of the two, Wikitude is arguably the easier one for nonprogrammers to use in developing AR content layers. For example, it has a web-based interface, which makes it easy to create simple AR experiences quickly. Those users with experience creating POI markers (or place marks) in Google Earth can simply import the KML file into the Wikitude developer's site — essentially allowing them to use Google Earth as a development environment.

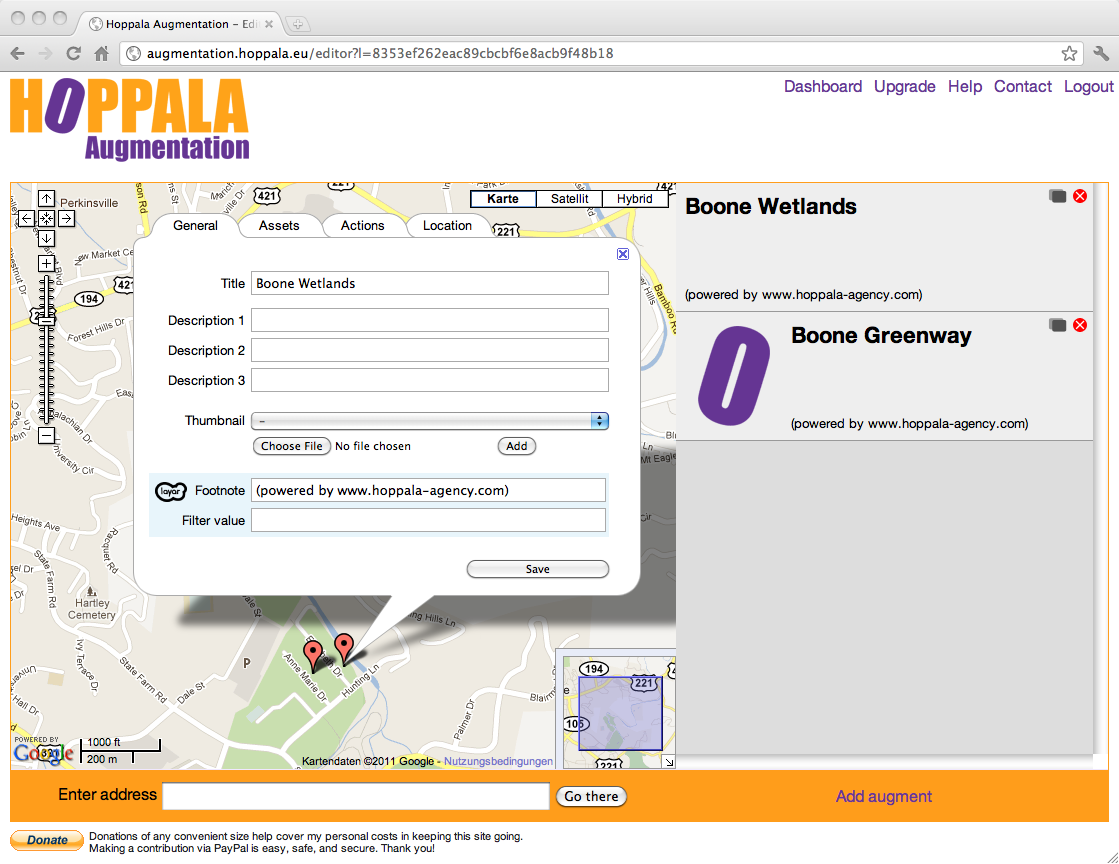

The Layar platform, on the other hand, poses more challenges to developers, yet it is a much more robust environment for creating game activities using POIs. Features of the Layar platform include letting players share content through Facebook and Twitter, playing audio and video files within a POI, including images and 3D objects in the layer, and having players log in to an account (to keep track of game play). Several third-party tools make it easier to develop Layar and Wikitude experiences. For example, Hoppala Augmentation, a web-based environment (shown in Figure 9), includes a map to place and edit POIs, complete with icons, images, audio, video, and 3D multimedia content.

Figure 9. Hoppala Augmentation Interface Integrates Google Maps to Create POIs

Mobile Game Activities at the Wetlands

One wetland game created by a student group, Bug Off, was developed in the SCVNGR platform, with challenges that include information and activities related to the importance of insects in the wetlands. During visits to the wetlands area at the Boone Greenway, the group received guidance on initial ideas from Wendy Patoprsty, extension agent for Natural Resources and Environmental Education at the North Carolina Cooperative Extension and director of the Watauga River Conservation Partners. In addition, I invited a colleague, Dr. Joy James, from the Recreation Management Program at Appalachian State University to consult with student groups near the completion of their projects, particularly in designing their games to be more engaging from the players' perspective.

Two of the challenges initially designed for Bug Off use the text and photo input of the SCVNGR platform (Figure 8). Therefore, at two physical locations at the wetlands area of Boone Greenway, a visitor playing the Bug Off game would see the following challenges:

- A Dragonfly flaps its wings over 2,000 times per minute! How many times can you flap your arms in a minute? Take a photo of your partner flapping her "wings." (challenge type: text input and photo input)

- In a single day, the dragonfly eats more than its own weight in mosquitoes. How many chicken nuggets would you have to eat in one day to equal your weight? (challenge type: text input)

A student-created video accompanies the challenge, helping students solve the weight question.

Figure 10 shows the "Bug Off" game in play.

Figure 10. Playing the "Bug Off" Mobile Game in SCVNGR

Assessment of the Project

In this project I was interested in examining two general research questions:

- Would the construction of games within a service-learning context increase students' positive attitudes toward community engagement and their interest in helping the community in general?

- Would the construction of games within a service-learning context result in increased positive attitudes toward collaboration within small-group peer groups, as well as with community partners and other university faculty assisting them with their projects?

To assess aspects of collaboration and community engagement in this project, I used both a survey and student reflections. The survey, administered after the course concluded, asked students to anonymously respond to questions about prior experiences at the Boone Greenway, their perceptions of the value of collaboration with community and classroom partners, and their perceptions of the community as a result of the project developing mobile learning games about wetlands education. The students wrote the reflections at a final meeting of the course, in responses to open-ended questions related to the value of collaboration with the community partner and resources that were beneficial to the development of the mobile learning games,

Community and Collaboration

All 19 students in the class completed the survey. All students were between the ages of 21 and 26 years old, with a nearly equal number of female (47 percent) and male students (53 percent).

Related to students' prior experiences at the Boone Greenway, fewer than half (42 percent) of the students had visited the recreation area prior to our course. Furthermore, I was interested in finding out whether students commonly go on field trips or meet off campus. Of these graduate students, 32 percent reported having field trips or meeting off campus at least once in previous university courses, whereas 68 percent reported having never done so prior to our course.

The survey also asked if the students' perceptions of the community have changed as a result of this project constructing mobile learning games. Table 1 shows responses indicating that students in the course are now interested in visiting the Greenway recreation area more often; they also show more positive attitudes toward helping the community in general. The responses offer a strong indication that the service-learning aspect of the project resulted in positive attitudes toward community engagement.

Table 1. Changes in Students' Perceptions of the Community

How has your perception of the community changed as a result of the mobile game project?

|

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| I am interested in visiting the Greenway more often | 0% | 0% | 5% | 63% | 32% |

| I am more interested now in helping the community | 0% | 0% | 21% | 63% | 16% |

Table 2 outlines several questions from the survey that address perceptions about project collaboration in two ways: peer group collaboration within the project, and faculty collaboration in the development of the mobile game.

First, a majority of students agreed (63 percent) or strongly agreed (21 percent) that working in a group on the project helped with learning more about the subject of mobile game development. Second, students found benefit in the collaboration of faculty from the Recreation Management program at the university, with all students reporting that Dr. James helped with the content for the games and that incorporating this collaboration would be a good model for the course in the future. Lastly, most students also felt that faculty collaboration could be helpful in other courses at the university, with 90 percent agreeing or strongly agreeing with that concept.

Table 2. Students' Attitudes Toward Collaborative Experiences

|

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| Working in a group helped me learn more about the subject than I would have working alone | 0% | 5% | 11% | 63% | 21% |

| I believe that having a collaborative faculty helped with the content of this course | 0% | 0% | 0% | 62% | 38% |

| I believe that having a collaborative faculty could be helpful in other courses at Appalachian State University | 0% | 0% | 10% | 58% | 32% |

Reflections on Community Partner and Faculty Collaboration

Many students remarked about the value of off-campus meetings at the Greenway wetlands and of working together on their game concepts with Wendy Patoprsty from the Watauga River Conservation Partners:

"She really informed me of all of the options that were available. I really thought that everyone would have the same type of game, but there are so many different aspects of the wetlands that she pointed out and different directions we could go."

"Her help touring the wetlands allowed us to map the game out and have the students playing our game explore the entire area."

"The field trips helped me realize that the game could teach so many different things to students and how we could use the game to show citizens and students alike how important the wetland area is to the town and the environment."

"Wendy was very helpful in helping us access the creative sides of our brains to make the game fun and engaging rather than merely educational."

"She provided us with a background of knowledge that was interesting to us and actually created excitement for creating our game."

Students also mentioned the value of faculty collaboration with Dr. Joy James from the Recreation Management Program at Appalachian State University consulting with groups on their game ideas. Many of these comments focused on how she helped groups make their games more engaging for a middle school–aged audience:

"[She] gave us a lot of good ideas to make our game more of a game that kids would enjoy and benefit from."

"Our game had very little direction until speaking with her. Her insight made us think about reaching our kids more effectively, and making it more fun for them."

"She made us think about how a younger child would think about our game. I think we changed or altered a couple of the challenges to keep the player engaged."

Recommendations and Lessons Learned

Upon reflection, I came up with several recommendations related to implementing this type of project in other courses and disciplines, as well as for other campuses and communities. In addition, I have identified some pros and cons of developing games in different platforms, along with the likely availability of mobile handsets for students in a course.

Implementation Across the Curriculum

First, with respect to implementing this type of project in other courses, I believe this model could be applied to many other disciplines: students engaged in developing a place-based mobile game either on campus or in the community by collaborating with community partners. For example, Appalachian State University has current service-learning projects related to preserving and enhancing the Blue Ridge Parkway through its affiliate organizations such as the Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation and FRIENDS of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Students in history, recreation management, and education, among other fields, could design games and other mobile learning experiences related to the Blue Ridge Parkway. For example, the College of Education currently sponsors the Blue Ridge Family Literacy Project, which is designed to preserve the history and culture of local communities and promote the development of emerging literacy skills through sharing of participants' digital stories. Education students could apply this mobile learning model to record and edit local personal histories, which then could be made available to visitors to the Blue Ridge Parkway using the mobile platforms presented in this article.

Language courses and overseas experiences could also incorporate mobile learning. The Mentira project, one of the ARIS (from the University of Wisconsin–Madison) AR games, focuses on language skills in Spanish, using interaction with simulated characters, other players, and local citizens. Having students develop similar types of mobile games in language learning courses or overseas courses could help them better understand language use in context.

Technical Considerations and Challenges

In my most recent course implementing mobile games within the community, I decided to focus on mobile game programs that could be used in the most popular current handsets and tablets: Mac iOS (iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch) and Android. A few programs that I have used in the past or am currently evaluating, such as Wherigo and ARIS, are not available for both platforms. However, with the ever-changing landscape of mobile platforms and software, I continue to evaluate new mobile tools that show promise. The biggest single issue that I face is that none of the current tools that are both cross-platform and easy to use were designed specifically for the purposes of creating mobile learning games. The most useful tool, SCVNGR, makes it easy for students to develop a game and allows awarding points for completing a challenge. However, it does not provide an easy way to moderate the awarding of points — as long as someone completes a challenge (either right or wrong), she is automatically awarded the points specified for that challenge.

Finally, considering the issue of availability of handsets, I am finding that more and more students in my courses come to class with a smartphone. In my latest course, nearly half had either an iPhone or Android device. Since students work in projects, it is necessary for one or two of the group members to have access to a smartphone for testing during the development of the project. Therefore, I also keep a handful of devices on-hand during this phase of the course. I secured a small grant this year to add a couple of new Android phones to my collection, and in the past have purchased used devices online.

I look for unlocked GSM phones, which allow me to purchase prepaid data services from AT&T and T-Mobile, with SIM cards that can be swapped from phone to phone for the different carriers. At the time of this writing, T-Mobile offered the most flexible data plan, the Web Day Pass, which provides 24 hours of unlimited data for $1.49. This plan is very useful for courses where students are testing in the field only one or two days a week, since the data plan only has to be activated on those days.

Another option, in areas that have Wifi connectivity — such as on campus — is to use iPod Touch devices for testing the games. The iPod Touch is generally less expensive to purchase than an unlocked mobile phone handset, and the latest generation includes a camera that can be used for QR Code, SCVNGR, and AR browser applications. Moreover, some colleges and media centers on campus might already have a set of iPods available for borrowing.

Conclusion

A project involving teachers creating mobile games related to groundwater on the island of Guam first led me to believe that the construction of games could be a valuable learning strategy. Most recently, a course this year at Appalachian State University involving students creating games within a service-learning context, in collaboration with a community partner, showed that this approach can increase students' interest in helping the community in general. Moreover, assessment of the project revealed a strong positive reaction to collaboration in three realms: small-group peer collaboration developing the mobile learning games, collaboration with a representative from a community partner in understanding fundamental concepts of the wetlands for game content, and collaboration with faculty from the university to further refine the game ideas.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to gratefully acknowledge the Department of Leadership and Educational Studies at Appalachian State University, which provided funds as part of a start-up research grant to purchase mobile handsets used in this study. In addition, the author would like to thank both Wendy Patoprsty, Extension Agent for Natural Resources and Environmental Education at the North Carolina Cooperative Extension, and Joy James, Assistant Professor of Recreation Management at Appalachian State University, for their assistance with student groups, in the content and design of mobile learning projects described in this study.

- Paul Wallace, "Development of a Place-Based Mobile Game for Groundwater Education," in Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education (SITE) International Conference 2009, Ian Gibson, Roberta Weber, Karen McFerrin, Roger Carlsen, and Dee Anna Willis, eds. (2009), pp. 3866–3871.

- Idit Harel and Seymour Papert, Constructionism (New York: Ablex Publishing, 1991).

- Yasmin Kafai, "Playing and Making Games for Learning: Instructionist and Constructionist Perspectives for Game Studies," Games and Culture, vol. 1, no. 1 (January 2006), pp. 36–40. doi:10.1177/1555412005281767

- Larry Johnson, Rachel Smith, H. Willis, Alan Levine, and Keene Haywood, The 2011 Horizon Report, New Media Consortium (2011).

- ETR Associates, "What Is Service-Learning?" National Service-Learning Clearinghouse (2011).

- John Dewey, Experience and Nature (Chicago: Open Court, 1925).

- Marc Prensky, "Students as Designers and Creators of Educational Computer Games: Who Else?" British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 39, no. 6 (July 2008), pp. 1004–1019.

- Marc Prensky, "In Digital Games for Education, Complexity Matters," Educational Technology, vol. 45, no. 4 (July/August 2005), pp. 22–28.

- Groundspeak Inc., Geocaching website (2011).

- Johnson et al., The 2011 Horizon Report.

© 2011 Paul Wallace. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 license.